Abnormal glucose regulation in psychiatric disorders, including manic-depression, was a focus of discussion and research in the first half of this century

(1–

13). Most of the reports comprised series of cases that are difficult to interpret and included few individuals with manic-depression. Gildea et al.

(14) reported elevated glucose tolerance test results after oral, but not intravenous, administration of dextrose to 30 manic-depressive subjects. Two other studies also found abnormalities in glucose regulation in patients with manic-depression; van der Velde and Gordon

(15) reported increased frequencies of abnormal results on glucose tolerance tests in manic patients compared with schizophrenic patients, and Lilliker

(16) reported increased rates of comorbid diabetes mellitus in patients diagnosed with manic-depressive disorder. Both of those reports were confounded by diagnostic systems that predated the separation of unipolar depression from manic-depressive disorder. The purpose of the current study was to evaluate whether patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder, manic or mixed subtype, according to the DSM-III-R criteria have a higher frequency of diabetes mellitus than the general population.

METHOD

Medical histories of 345 patients admitted to John Umstead Hospital who met the DSM-III-R criteria for bipolar disorder, manic or mixed subtype, were evaluated for a comorbid diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. John Umstead Hospital is a state psychiatric hospital serving 14 counties in the north central region of North Carolina. The vast majority of patients are admitted directly from either mental health centers or emergency rooms located within this region. Chi-square analyses comparing the presence or absence of diabetic comorbidity with sex, race (white versus black), and diagnostic subtype (manic versus mixed) were computed. The mean ages of the diabetic and nondiabetic patients within the study group were compared by means of t tests.

The frequency of diabetes mellitus in the U.S. population aged 20–74 years has been estimated at 3.4%

(17), with a higher rate among blacks (5.2%) than among whites (3.2%). A higher rate of diagnosed diabetes in women (3.8%) than in men (2.9%) has also been suggested, although this difference reaches significance only within some age groups. To facilitate a comparison of the frequency of diabetes mellitus in persons with bipolar illness and in the general population, we restricted our study group to the racial composition and age range of the subjects in the study by Harris et al.

(17). We categorized our restricted group according to the same race (black or white), sex, and age groups (i.e., ages 20–44, 45–54, 55–64, and 65–74 years) and calculated a weighted average for the expected frequency of diabetes in our entire study group by using the frequencies in each of the same subgroups within the Harris et al. comparison study. Using this overall estimate, we determined the expected number of subjects drawn from the general U.S. population in a similar-size group who would have a self-reported history of diabetes mellitus and compared the two groups using a goodness-of-fit chi-square analysis. The comparison study

(17) that we used to determine those rates, like ours, did not distinguish between type I and type II diabetes mellitus. The overall frequency of type I diabetes mellitus relative to type II is low

(18), and the majority of cases would be expected to represent type II.

Diabetic bipolar patients whose previous psychiatric histories were available were matched by age (within 4 years) to randomly selected nondiabetic bipolar patients from the total study group. Age at first psychiatric hospitalization and number of lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations were compared for the groups by means of Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests and a Bonferroni correction applied to significance levels. In addition, diagnostic subtypes (manic versus mixed) of the two groups were compared by means of chi-square tests.

RESULTS

The initial cohort included 357 patients meeting the DSM-III-R criteria for bipolar disorder, manic (N=309) or mixed (N=48) subtype. This group consisted of 172 men and 185 women. Two hundred twelve patients were white, 143 were black, one was Oriental, and one was American Indian. Their mean age was 42.1 years (SD=13.8, range=18–82).

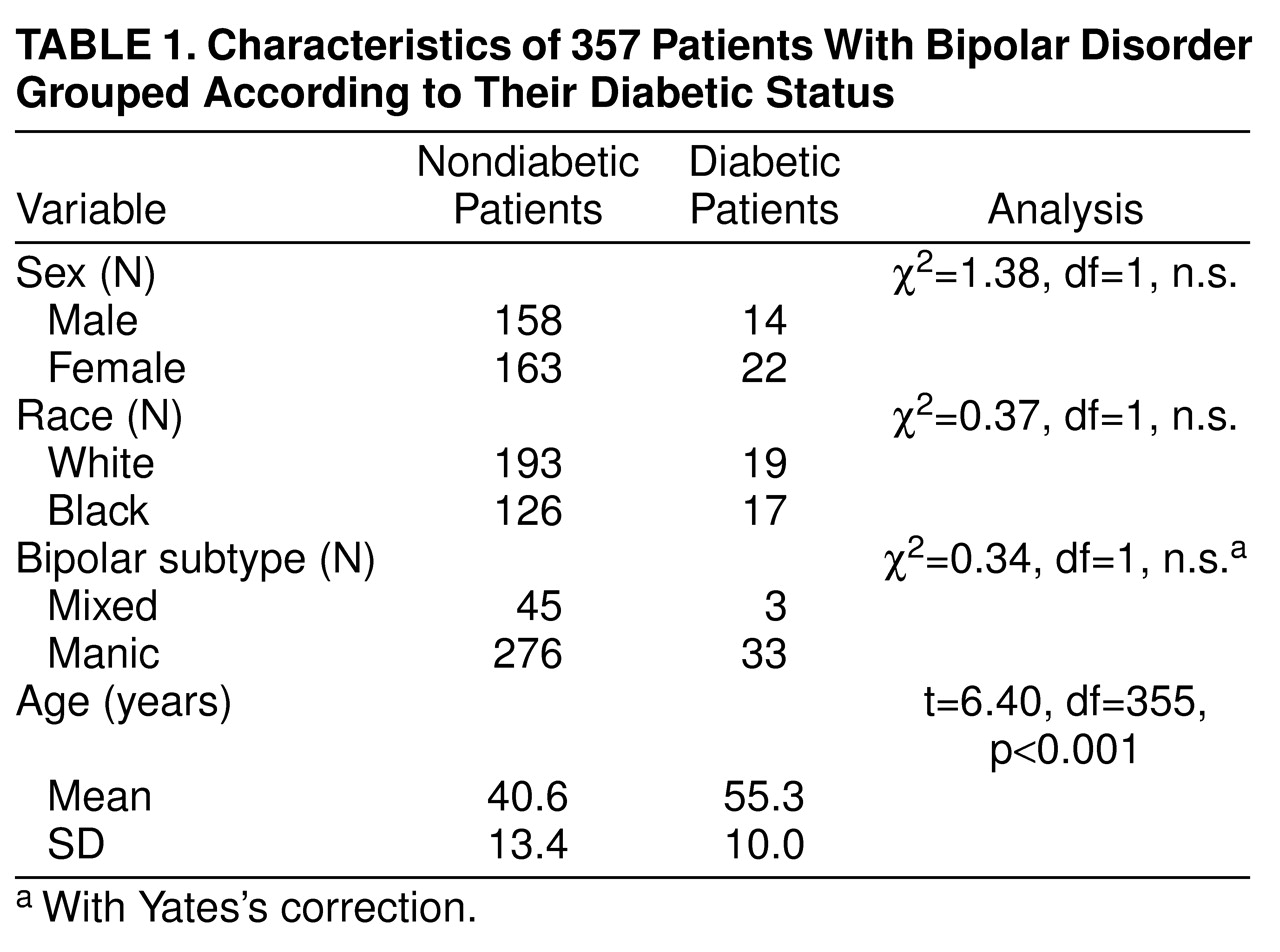

The raw prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the initial cohort was 10.1% (N=36). These 36 patients had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus before their current psychiatric hospitalization. Characteristics of the diabetic and nondiabetic patients are shown in

Table 1. The results of chi-square analyses were not significant for diagnostic subtype (mixed versus manic), race (white versus black), or sex, but the difference in the mean ages of the diabetic and nondiabetic groups was significant.

To facilitate a comparison with the reported frequency of diabetes mellitus in the U.S. population, four patients under the age of 20 were excluded (none was diabetic), six patients 75 years of age or older were excluded (two of whom were diabetic), and the one Oriental patient and the one American Indian patient were excluded (neither was diabetic). The remaining group comprised 345 white and black subjects aged 20–74 years and represented 96.6% of the initial cohort. One hundred seventy subjects were male and 175 were female. Two hundred seven were white and 138 were black.

The frequency of diabetes mellitus in this final group aged 20–74 years was 9.9% (N=34). The expected frequency of diabetes mellitus, based on the calculated frequency weighted for age, sex, and race from the comparison study groups

(17), was 3.5%, which is equivalent to 12 of 345 subjects, minimally higher than the 3.4% calculated in the entire cohort of the comparison study. The frequency of diabetes mellitus was significantly higher in our bipolar patients (χ

2=41.80, df=1, p<0.001).

For the comparison of the diabetic and age-matched nondiabetic bipolar patients, complete psychiatric histories were obtained for 29 (81%) of the 36 diabetic patients (seven white men, five black men, seven white women, and 10 black women). Their mean age was 55.6 years (SD=10.3). Three of these subjects met the criteria for bipolar disorder, mixed subtype, and 26 for bipolar disorder, manic subtype. The mean age of the matched nondiabetic bipolar comparison patients was 55.6 years (SD=10.0). This group consisted of seven white men, four black men, 11 white women, and seven black women. Three of them met the DSM-III-R criteria for bipolar disorder, mixed, and 26 for bipolar disorder, manic. As expected, the mean ages of the two groups did not differ (t=–0.01, df=56, n.s.). The maximum age difference for matching nondiabetic patients to the diabetic patients was 4 years, but 27 (93%) of the 29 nondiabetic patients were matched to within 2 years of age. The groups did not differ with respect to manic subtype (χ2=0.19, df=1, n.s.), sex (χ2=0.00, df=1, n.s.), or race (χ2=0.63, df=1, n.s.).

The age at first psychiatric hospitalization in the diabetic subgroup (mean=34.0 years, SD=12.1) did not differ significantly from that of the matched nondiabetic group (mean=37.1 years, SD=10.8) (z=0.91, n.s.). However, the total number of psychiatric hospitalizations in the diabetic group (mean=10.9, SD=10.5) was significantly greater than that in the age-matched comparison group (mean=5.3, SD=5.2) (z=–2.26, p<0.05). The age at onset of diabetes mellitus could not be determined reliably in these patients.

DISCUSSION

The overall frequency of diabetes mellitus (10.1%) in our cohort of patients with bipolar disorder, manic and mixed subtypes, is similar to the 10% frequency reported by Lilliker

(16). Although a direct comparison of our group with population norms may be limited by methodological differences and selection biases, this 10.1% rate of diabetes mellitus in our manic cohort is well above the rate in the general population (3.4%). In this study we based our comparison group on national frequency norms of previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus. Our study and the comparison study

(17) used similar standards for the identification of diabetic histories. In the comparison study, rates of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus were also estimated by administering glucose tolerance tests to all subjects with no previous history of diabetes mellitus. When we use a comparison group that includes both previously diagnosed cases and previously undiagnosed cases, the frequency of diabetes mellitus in our bipolar study group is still greater than expected (χ

2=6.99, df=1, p<0.01). Although we controlled for age and sex in our comparison groups, the possibility of other confounding variables was not excluded. Nevertheless, the frequency of diabetes mellitus in our cohort was well above the expected 3.5%. Possible explanations for this comorbidity include a genetic relationship between the two diseases, a causal relationship in which the development of diabetes mellitus or mania increases the risk of the development of the other disorder, or a functionally overlapping disturbance present in both diseases.

Each of these possibilities derives some support from our understanding of these diseases. Although the genetics of bipolar disorder is not well understood, there is a consensus that multiple genes are likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of manic-depression

(19). The tyrosine hydroxylase-INS-insulin-like growth factor II gene cluster on the short arm of chromosome 11 has been implicated as a susceptibility locus for diabetes mellitus

(20,

21). Although initial reports of the INS gene being a susceptibility locus for bipolar disorder

(22) were subsequently discounted after a reanalysis of a larger sample

(23), tyrosine hydroxylase markers have been shown to have some associations with bipolar disorder

(24–

26).

Although high rates of cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease are well recognized in persons with diabetes mellitus, few studies have addressed the issue of cerebrovascular disease in diabetic subjects

(27). Higher rates of lesions of small intraparenchymal cerebral vessels and focal infarction have been reported in diabetic patients

(28–

31). Those lesions have occurred mainly in areas with blood supply from direct midline or parasagittal arteries serving areas such as the base of the pons, thalamus, and basal ganglia

(31). Although it is not known whether diabetes-related vascular lesions that occur in the brain can result in psychopathology, subcortical white matter lesions have also been observed in T

2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans in bipolar disorder

(32–

37). Moreover, diabetes mellitus has been implicated as a risk factor for similar hyperintensities on T

2-weighted MRI scans

(38).

Manic episodes might also predispose to the development of diabetes mellitus. Increased glucocorticoids have been reported to induce diabetes mellitus

(39), and hypercortisolemia has been reported during depressive episodes

(40–

44) and, by some researchers, during manic or mixed episodes

(45–

50).

The two diseases may also affect similar systems or areas of the brain. Both diabetes mellitus and mania have associated disturbances of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, as reflected by high rates of nonsuppression of cortisol on the dexamethasone suppression test

(51–

54). Moreover, the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus has been implicated both in disturbances of the sleep-wake cycle noted during mania

(55) and in the regulation of glucose metabolism

(56).

Although the exact relationship between bipolar disorder and diabetes mellitus is not known, the association between these disorders is clinically relevant and underscores the importance of screening for diabetes mellitus in the bipolar population, particularly because earlier detection and control of diabetes mellitus is considered important for prevention of the medical comorbidity of diabetes mellitus and for prevention of cerebral microvascular disease that may exacerbate the course of bipolar disorder. For example, the greater frequency of serious episodes of mania requiring hospitalization among the diabetic manic patients in our study be due to cerebral microvascular disease. Moreover, psychotropic medication may further increase the risk of the development of diabetes, either directly or as a result of weight gain. Further controlled studies of the relationship of these two disorders are warranted.