Recent estimates suggest that the prevalence of pathological gambling in the adult population is 1.1% (12-month) and 1.6% (lifetime)

(1). Previous research has documented high rates of psychiatric comorbidity in pathological gamblers but, to our knowledge, has not compared the characteristics of gamblers with and without comorbid disorders

(2).

Because presence of psychiatric comorbidity may influence the severity of illness, treatment selection, and outcome, it is important to evaluate the frequency and type of comorbid psychiatric disorders among pathological gamblers seeking treatment. We studied the psychiatric comorbidity of pathological gamblers who consecutively applied for treatment and compared the clinical and genetic characteristics of the gamblers with and without comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Method

Sixty-nine consecutive patients seeking treatment at the Hospital Ramón y Cajal in Madrid (47 men and 22 women) were evaluated for gambling behavior and associated psychopathology after providing signed informed consent. The South Oaks Gambling Screen

(3) was given to the patients before all other evaluations. All patients met DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling and were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-III-R (versions for axis I and axis II disorders), Global Clinical Impression

(4), Beck Depression Inventory

(5), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

(6), and Zuckerman’s Sensation Seeking Scale

(7). Clinicians were blind to the subjects’ scores on the psychological questionnaires. Allele distribution of the dopamine D

2 receptor gene (

DRD2) polymorphism was analyzed

(8). Chi-square tests were used to analyze differences in the distribution of categorical variables, and t tests were used for continuous variables. All tests were considered significant at the alpha=0.05 (two-tailed) level. Multiple regressions were used to control for gender and gender-by-comorbidity interactions in the distribution of the variables.

Results

Forty-three (62.3%) of the subjects with pathological gambling had an associated psychiatric comorbid disorder at the time of evaluation. Twenty-four patients (34.8%) had one comorbid disorder, 17 (24.6%) had two comorbid disorders, and two (2.9%) had three disorders. Current comorbid disorders included alcohol abuse or dependency (N=16 [23.2%]), adjustment disorders (N=12 [17.4%]), antisocial personality disorder (N=10 [14.5%]), other personality disorders (N=19 [27.5%]), mood disorders (N=6 [8.7%]), anxiety disorders (N=3 [4.3%]), and substance abuse (N=2 [2.9%]). Lifetime comorbid diagnoses included alcohol abuse or dependence (N=24 [34.8%]), mood disorders (N=11 [15.9%]), and anxiety disorders (N=5 [7.2%]). Significantly more men had current comorbid alcohol abuse/dependency than women (N=15 [31.9% of 47] versus N=1 [4.5% of 22]) (χ2=6.5, df=1, p=0.01), whereas more women had comorbid mood disorders (N=5 [22.7%] versus N=1 [2.1%]) (χ2=8.0, df=1, p=0.005). There were no gender differences in the current or lifetime frequencies of other disorders or in sociodemographic characteristics between the gamblers with and without comorbid disorders.

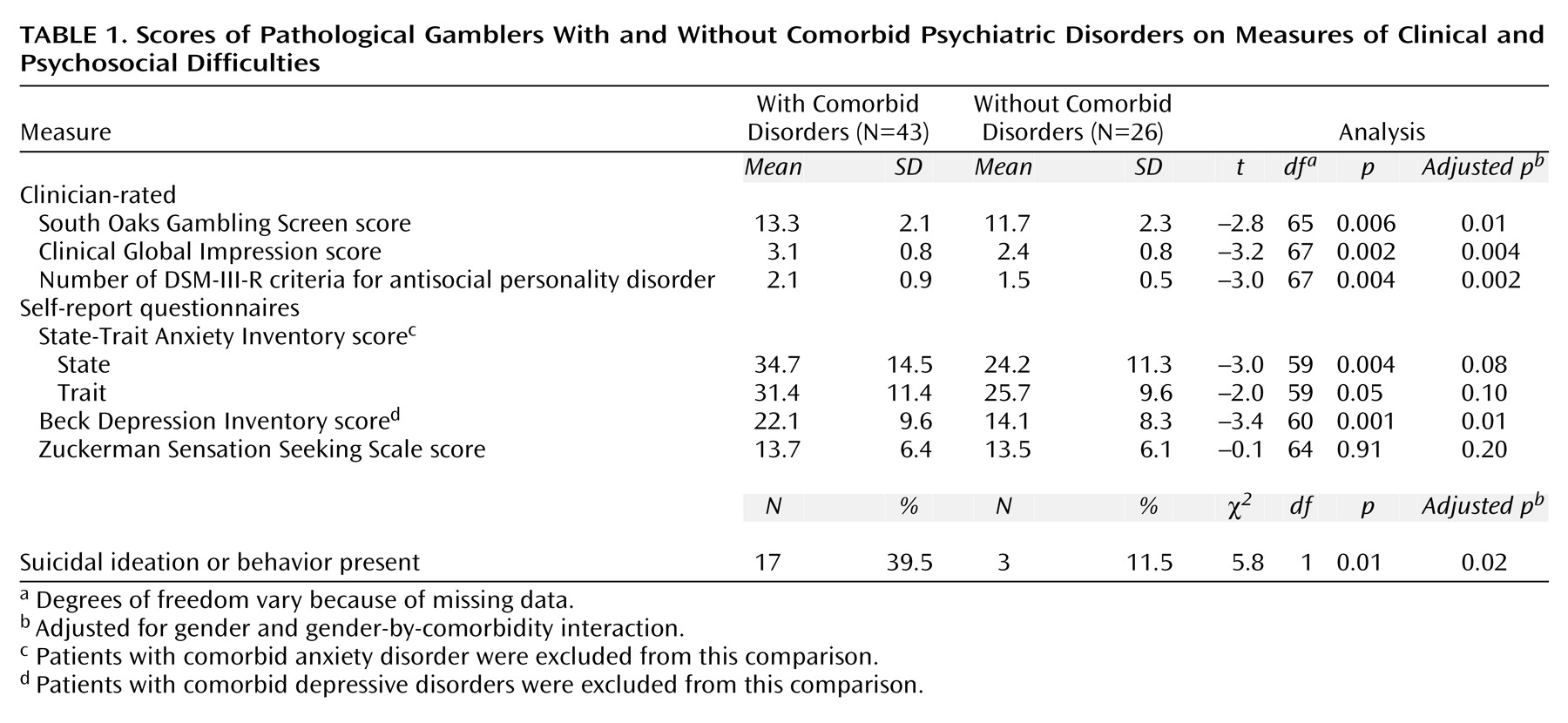

Gamblers with comorbid psychiatric disorders had significantly higher scores on the South Oaks Gambling Screen (indicating greater severity of gambling), and severity increased linearly with the number of comorbid diagnoses (r=0.40, df=64, p<0.001). They also had significantly higher scores on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory (even after patients with comorbid anxiety and mood disorders, respectively, were excluded). Most of these differences remained significant after we adjusted for gender and gender-by-group (presence versus absence of comorbidity) interaction using multiple linear regression (

Table 1).

Allele distributions of the DRD2 polymorphism were significantly different in the gamblers with and without comorbid disorders (χ2=13.9, df=1, p=0.003). Allele C4 was present in 21 (42.0%) of the 50 gamblers with a lifetime history of comorbid disorders, compared with one (5.3%) of the 19 gamblers without comorbid disorders (χ2=7.0, df=1, p=0.008). A linear regression with South Oaks Gambling Screen as the outcome variable and presence of comorbidity, presence of the C4 allele, and the interaction term as predictors showed that the association between comorbidity and severity remained significant after adjusting for presence of the C4 allele (t=2.4, df=67, p=0.02).

Discussion

Confirming previous studies (2), this study of consecutive treatment-seeking pathological gamblers found a high rate and wide range of comorbid psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, we found that presence of comorbid disorders was associated with more severe gambling behavior and psychopathology. Because pathological gambling is frequently treated in specialized clinics, there is a risk that treatment may focus on gambling alone. Our findings underscore the need to conduct comprehensive evaluations of pathological gamblers and to devise treatment plans that appropriately address their comorbid illnesses. Retrospective studies suggest that simultaneous treatment of pathological gambling and alcohol dependence improve the outcome of pathological gambling treatment

(9). Prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and test their applicability to other comorbid psychiatric disorders.

The majority of gamblers with comorbid disorders had an associated substance-related disorder, suggesting that those disorders may be nosologically related either by predisposing to one another or by sharing common neurobiological mechanisms. The design of our study, however, did not allow us to examine the temporal relationship between these disorders. In contrast, we did not find any cases of obsessive-compulsive disorder, suggesting that their link with pathological gambling may be weaker than has been reported

(2). Similarly, we found a low rate of comorbid mood disorders but a high number of patients with adjustment disorders, probably due to the outpatient setting of the study.

In our study group, pathological gamblers with comorbid psychiatric disorders were more severely affected than those without comorbid disorders according to clinician-rated measures and psychological questionnaires. Although the clinician may have systematically underrated one of the two groups, the average South Oaks Gambling Screen scores of each group, rated blind to whether the patient had comorbid disorders, do not support that explanation. Our findings of an association between

DRD2 allele distribution and comorbid pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders supports the role of this gene as a liability factor for psychiatric disorders

(10). However, only the presence of comorbid disorders, not presence of the

DRD2 C4 allele or the interaction term, was associated with gambling severity as measured by the South Oaks Gambling Screen.

Our study is limited by its cross-sectional nature, the lack of additional comparison groups (e.g., subjects with a primary diagnosis of substance abuse disorders), and the absence of data on treatment outcome. Future studies should look at the longitudinal course of gamblers with and without comorbid psychiatric disorders (including diagnosis of new patients with comorbid disorders) and the impact of comorbidity on the rates of retention in and response of patients to treatment.