Factor Structure of the SWAP-200

We conducted a second factor analysis using the entire 200 items contained in the SWAP-200. The items were subjected to principal-component analysis. We examined the resulting eigenvalues, the percent of variance accounted for by each principal component, and the scree plot. The scree plot showed no clear break, with a gradual leveling between 10 and 20 factors. (This relatively large number of factors is consistent with the findings of Clark and colleagues, who used self-report instruments designed for personality disorder samples [

3,

41].) Seventeen of the principal components cumulatively accounted for approximately half (50.2%) of the variance in the item set. Thus, we retained and varimax-rotated 17 factors. The first 12 of the rotated factors proved theoretically coherent, readily interpretable, and well marked by multiple items.

(Eigenvalues for the first 12 principal components ranged from 2.7 to 23.9, accounting for 1.35% to 11.95% of the variance each. Scale reliabilities [coefficient alpha] for the 12 rotated factors ranged from a high of 0.94 [factor I] to a low of 0.59 [factor 10], with all other scales showing reliability >0.70.)

To verify the stability of the 12 factors, we performed additional factor analyses specifying fewer factors and more factors and consistently obtained similar factor solutions. We also performed a second factor analysis using oblique (promax) rotation. The results of the two approaches were virtually identical; for ease of presentation, we report results based on orthogonal rotation.

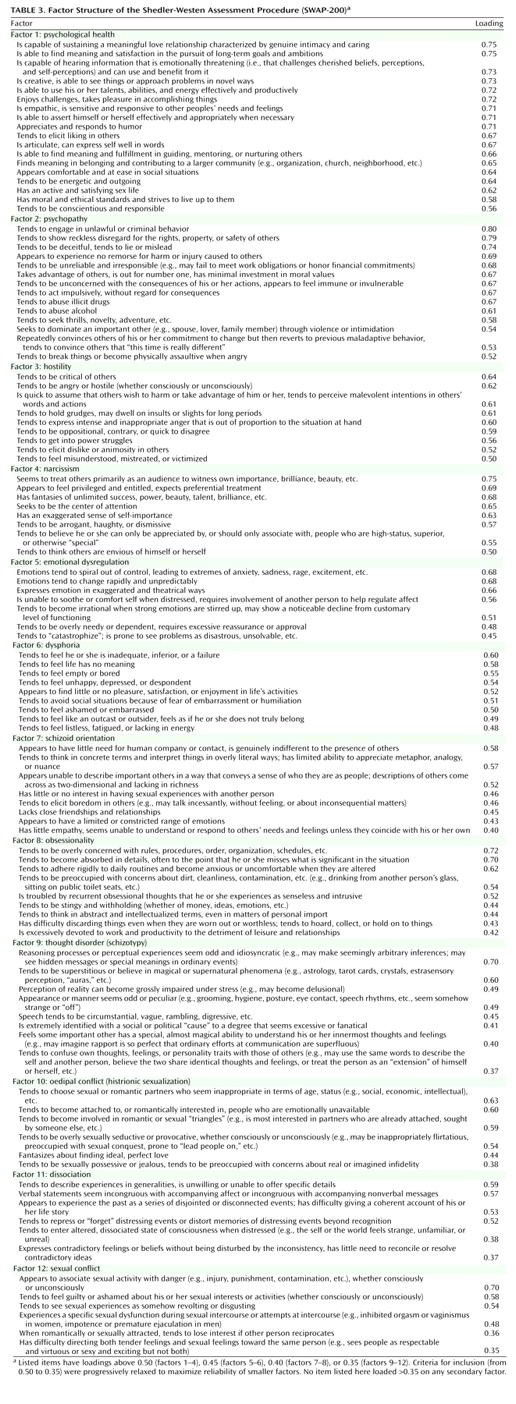

Table 3 lists the items that load most highly on each of the 12 factors in descending order of factor loading. There appears to be little question about the interpretation of any of the factors.

Factor 1, psychological health, assesses the positive presence of psychological strengths and inner resources, including the capacity to love, find meaning in life experiences, and gain insight into self and others.

Factor 2, psychopathy, includes features associated not only with antisocial personality disorder but also with the classical clinical construct of psychopathy (42, 43), such as lack of remorse, a seeming imperviousness to consequences, impulsivity, and a tendency to abuse alcohol and drugs.

Factor 3, hostility, is straightforward and requires no interpretation. It resembles the five-factor model neuroticism facet of the same name.

Factor 4, narcissism, reflects self-importance, grandiosity, entitlement, and the tendency to treat others as audiences to provide admiration. The factor taps a core construct in contemporary clinical thought.

Factor 5, emotional dysregulation, refers to a deficiency in the capacity to modulate and regulate affect, so that affect tends to spiral out of control, change rapidly, get expressed in intense and unmodified form, and overwhelm reasoning. This construct is crucial to an understanding of borderline personality disorder and has no five-factor model equivalent.

Factor 6, dysphoria, captures depression, anhedonia, shame, humiliation, and a number of their cognitive and affective correlates. The factor is closely related to the five-factor model neuroticism factor.

Factor 7, schizoid orientation, bears a family resemblance to the extreme negative pole of extroversion, but a review of the items shows this to be a distinct and clinically richer construct. Patients high on this dimension do not just keep to themselves. They are also concrete in their thinking, barren in their representations of others (as reflected by an inability to describe others in meaningful ways), have constricted emotions, and have little capacity for empathy. In contrast, many introverts are reflective about themselves and others, feel emotion intensely, and are sophisticated and abstract in their thinking.

Factor 8, obsessionality, bears a family resemblance to the five-factor model conscientiousness factor. Note, however, that the obsessionality factor describes not only hyperconscientiousness but a cognitive and defensive style that includes absorption in details, intellectualization, preoccupation with dirt and contamination, intrusive and obsessional thoughts, stinginess, and difficulty discarding things. It appears related to the historical construct of obsessionality (see references

44,

45).

Factor 9, thought disorder (or schizotypy), captures a phenomenon of crucial clinical import that has no five-factor model equivalent (as acknowledged by McCrae

[46]). (With respect to research on psychotic spectrum disorders, this factor appears to assess characterological and subsyndromal positive symptoms; the schizoid orientation factor appears to assess subsyndromal negative symptoms.)

Factor 10, oedipal conflict, includes a constellation of items reflecting triangulated romantic relationships that always involve a third-party competitor, choosing romantic partners who are unavailable or inappropriate, sexual jealousy, and excessive or inappropriate seductiveness. Some readers may prefer the label “histrionic sexualization.” Regardless of one’s preferred terminology, the factor captures an important clinical phenomenon with no five-factor model equivalent.

Factor 11, dissociation, describes incongruity and disconnectedness between affect, cognition, and memory that is often associated with a developmental history of trauma or abuse. This construct is of crucial clinical import, especially for individuals who have been victims of complex trauma and for many patients diagnosed with borderline personality pathology. The construct has no five-factor-model equivalent.

Factor 12, sexual conflict, describes a conflicted orientation toward sexuality, including the association of sexuality with danger (whether consciously or unconsciously), and guilt, shame, revulsion, or disgust in connection with sexuality. The factor is not represented in the five-factor model. From a clinical perspective, the absence of items to assess sexuality is a particularly salient omission in the five-factor model. It is also a significant omission from the perspective of evolutionary psychology.

Ruling Out Alternative Hypotheses

A critic might argue that the 12-factor solution reflects not so much the personalities of the patients but rather the shared cognitive schemas of the clinicians who provided the data. In this case, the factor solution would reveal more about the beliefs of clinicians than the characteristics of their patients (this same criticism has been directed against the five-factor model itself [

47,

48]).

The strongest version of the “cognitive schema” argument might run as follows. Nearly half of the participating clinicians reported a psychodynamic orientation. Could the factor solution therefore be a function of their shared theories?

To explore this rival hypothesis, we eliminated clinicians from the data set who identified their orientation as psychodynamic and reanalyzed the SWAP-200 data contributed by the remaining 257 nonpsychodynamic clinicians. The factor solution was virtually identical; the only substantive difference was that the 12th factor became a self-destructive factor and the sexual conflict items loaded on a 13th factor.

Another possibility is that the 12 SWAP factors are lower-level facets of the five-factor-model factors. If so, the factors could themselves be factor-analyzed, and the resulting higher-order factors should resemble the five-factor model. To explore this, we subjected the SWAP-200 factors to higher-order factor analysis using the strategy adopted by Clark, Livesley, and colleagues

(49). We first created variables to represent each factor by averaging items with loadings of 0.50 or higher (or above 0.35–0.40 if fewer than eight items had loadings >0.50). We then factor-analyzed these 12 variables. The resulting scree plot showed no clear break. We nevertheless retained and varimax-rotated five factors.

The five-factor solution did not yield higher-order factors that were easily interpretable, and the factors did not resemble the five-factor model. The first higher-order factor was marked by schizoid orientation, dissociation, and psychological health (negative loading); the underlying construct is not readily apparent. The second higher-order factor was marked by narcissism, dysphoria (negative loading), and psychopathy; again, the underlying construct is not readily apparent, although one might stretch to label it malignant narcissism. The third higher-order factor was marked by one variable: obsessionality (which has often loaded on its own factor in prior research factoring axis II criteria, e.g., reference

50). The fourth higher factor was marked by sexual conflict and oedipal conflict and hence might be labeled problematic sexuality. The fifth higher-order factor was marked by emotional dysregulation and hostility; again, the underlying construct is difficult to discern, although it may reflect borderline affectivity.

The higher-order factors lack theoretical coherence and appear to bring less rather than more order to the data. We performed additional higher-order factor analyses, retaining and rotating three, four, and six higher-order factors, using both orthogonal and oblique rotations, but failed to find higher-order factors that resembled five-factor model factors.