A number of controlled trials have suggested that cognitive behavior strategies may decrease the risk of relapse in major depressive disorders

(1–

5). The risk of relapse in depression is strongly related to the number of depressive episodes and to the amount of residual symptoms

(6). Frank et al.

(7) conducted a randomized 3-year maintenance program in 128 patients with recurrent depression who had responded to combined short-term and continuation treatment with imipramine and interpersonal psychotherapy. A five-cell design was used to determine whether imipramine, placebo, and interpersonal psychotherapy could play a role in the prevention of recurrence. The use of imipramine at an average dose of 200 mg/day provided the strongest prophylactic effect, whereas monthly interpersonal psychotherapy displayed a modest protective effect, although the latter was superior to placebo

(7). The clinical consequence of this investigation is that patients with recurrent depression merit continued antidepressant drug prophylaxis. A sequential approach (based on the use of pharmacotherapy in the acute phase of depression and cognitive behavioral therapy in its residual phase) was applied to 40 patients with recurrent major depression, who had been successfully treated with antidepressant drugs by using the same criteria that had been outlined by Frank et al.

(7). Those were three or more episodes of unipolar depression (with the immediately preceding episode being no more than 2.5 years before the onset of the present episode). Patients were randomly assigned to either cognitive behavior treatment of residual symptoms—supplemented by lifestyle modification and well-being therapy

(8)—or clinical management. In both groups, antidepressant drugs were tapered and discontinued. At the 2-year follow-up, cognitive behavior treatment resulted in a significantly lower relapse rate (25%) than did clinical management (80%)

(3). The differential relapse rate was found to be significantly related to the abatement of residual symptoms

(9).

The aims of this investigation were to extend the follow-up to 6 years and to further explore therapeutic tools when, regardless of previous treatment (cognitive behavior or clinical management), relapse ensued.

Method

Patients

Forty-five consecutive outpatients satisfying the criteria to be described, who had been referred to and treated in the Affective Disorders Program of the University of Bologna, were enrolled in this study. The patients’ diagnoses were established by the consensus of a psychiatrist (G.A.F.) and a clinical psychologist (C.R.), independently using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia

(10). Subjects had to meet the following criteria:

1) Having a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder according to the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)

(11)2) Having their third or subsequent episode of depression, with the immediately preceding episode being no more than 2.5 years before the onset of the present episode

3) Reporting a minimum 10-week remission according to the RDC (no more than two symptoms present to no more than a mild degree with an absence of functional impairment) between the index episode and the immediately preceding episode

(7)4) Having a minimum global severity score of 7 for the current episode of depression

(12)5) Having no history of manic, hypomanic, or cyclothymic features

6) Having no history of active drug or alcohol abuse, dependence, or personality disorder, according to DSM-IV criteria

7) Having no history of antecedent dysthymia

8) Having no active medical illness

9) Having a successful response to antidepressant drugs administered by two psychiatrists (S.G. and S.C.), according to standardized protocol

(13).

This protocol involved the use of tricyclic antidepressants, with gradual increase in dose. Patients who could not tolerate tricyclics were switched to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

(3).

After drug treatment, all patients were assessed by the same psychologist who had evaluated them at intake but who did not take part in the treatment. Only the patients rated as “better” or “much better” according to a global scale of improvement

(12) and as in full remission

(14) were enrolled in the study. The subjects also had to show no evidence of depressed mood after treatment, according to a modified version of Paykel’s Clinical Interview for Depression

(15).

All patients were treated for at least 3 but no more than 5 months with full doses of antidepressant drugs

(3), after which the modified version of Paykel’s Clinical Interview for Depression

(15) was administered by the clinical psychologist. This interview covered 19 symptom areas, as described in detail elsewhere

(10). After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Treatment

After assessment with the Clinical Interview for Depression, the 45 patients were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: 1) pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavior treatment or 2) pharmacotherapy and clinical management. In both cases, treatment consisted of 10 30-minute sessions once every other week.

Antidepressant drugs were tapered at the rate of 25 mg of amitriptyline or its equivalent every other week, and then they were withdrawn completely (in all cases, in the two last sessions, the patients were drug free). This was not feasible for five patients (three in the cognitive behavior treatment and two in the clinical management groups), who were therefore excluded from the study at that point. The same psychiatrist (G.A.F.) performed all treatments in both groups.

Cognitive behavior treatment consisted of the following three main ingredients: cognitive behavior treatment of residual symptoms of major depression, lifestyle modification, and well-being therapy, as described in our previous article

(3).

The 40 subjects were reassessed with the Clinical Interview for Depression, after treatment and while drug free, by the same clinical psychologist who had performed the previous evaluations and who was blind as to treatment assignment. The patients were then assessed 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 54, 60, 66, and 72 months after treatment. They were instructed to call immediately if any new symptoms appeared and were guaranteed a renewed course of antidepressant drug therapy only in the event of relapse. Follow-up evaluation consisted of an update of clinical and medical status, including any treatment contacts or use of medications. Relapse was defined as the occurrence of an RDC-defined episode of major depression. During follow-up (unless a relapse occurred), no patient received additional antidepressant drug treatment or psychotherapeutic intervention.

When a first relapse ensued, patients were treated with the same antidepressant drug that had been used in the previous episode, for the same duration, and with the same modalities. Clonazepam (0.5 mg b.i.d.) was added to the treatment regimen and continued when the antidepressant drug was stopped. If a second relapse during the 6-year follow-up occurred, clonazepam was discontinued, and the patients were treated again with the same antidepressant drug, which, however, was then maintained throughout the study period at the same dose, which yielded remission. Remission was defined according to the same criteria already specified for enrollment.

Statistical Methods

Fisher’s exact test and two-tailed t tests were used to compare the two groups. Survival analysis

(16) was used for time until relapse into major depression. Six factors were investigated as possible predictors of outcome: assignment to cognitive behavior treatment or clinical management, age, sex, duration of the depressive episode, number of previous depressive episodes, and number of residual symptoms regardless of, and before, treatment assignment. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for estimating survival curves. Since relapse was the event of interest, survival referred to relapse-free status. Each factor was dichotomized, with a cutoff point around the median for measurement-type factors. The log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare any survival distributions for each of the six factors considered. For all tests performed, the significance level was set at 0.05, two-tailed. Results are expressed as means and standard deviations.

Results

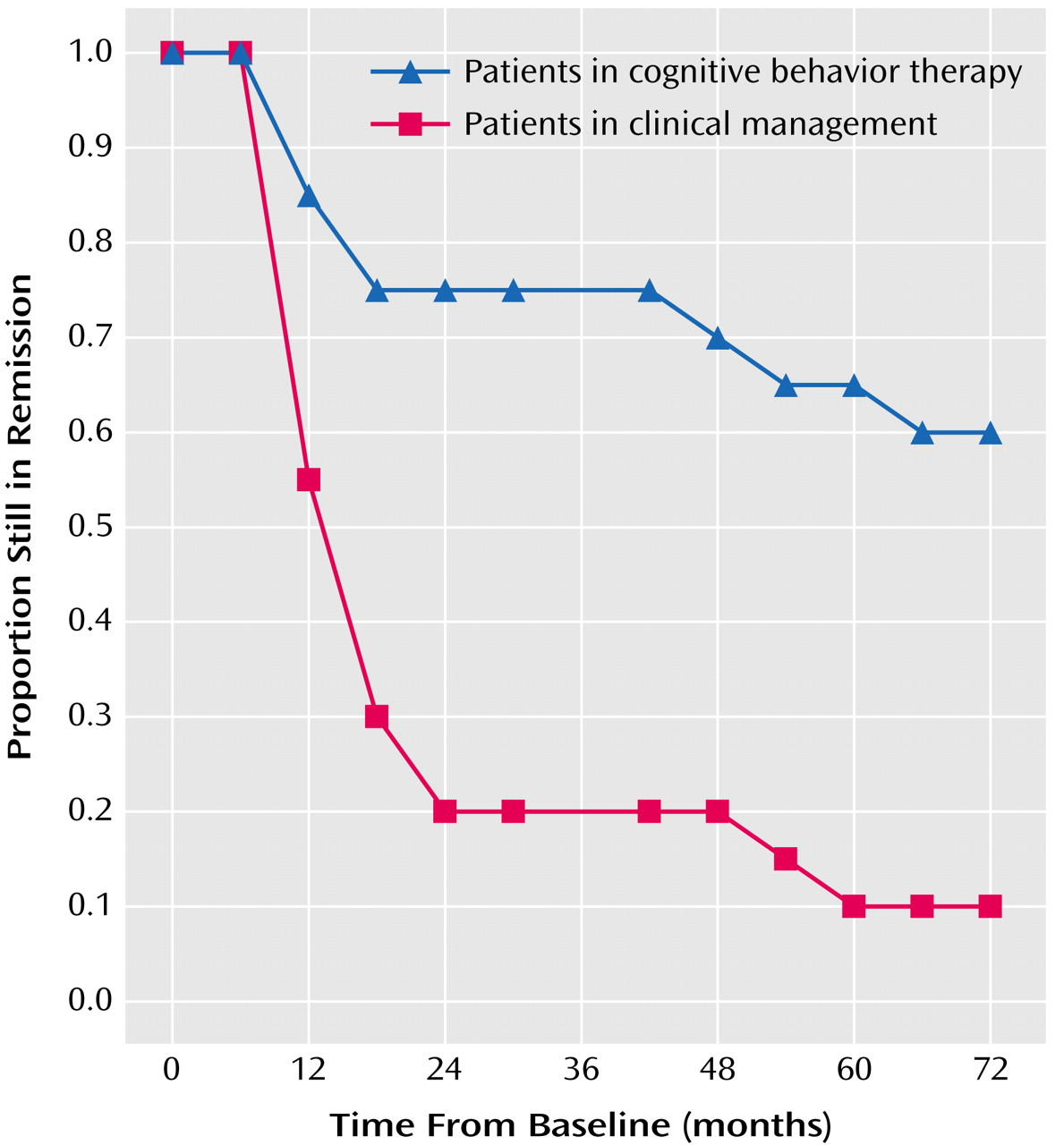

All 40 patients (20 in each group) completed the 6-year follow-up. During this period, eight (40%) of the patients in the cognitive behavior treatment group and 18 (90%) in the clinical management group relapsed at least once. The difference was significant (p=0.001, Fisher’s exact test). The mean survival time was 235.0 weeks (SD=111.7) for the cognitive behavior treatment and 95.5 weeks (SD=93.3) for the clinical management group (t=4.29, df=38, p<0.001). Of the six variables selected for survival analysis, only treatment assignment (

Figure 1) attained statistical significance (χ

2=13.82, df=1, p<0.001, log-rank test). When we used the Cox proportional hazards model, cognitive behavior treatment had a significant effect in delaying recurrence (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test).

Four of the eight patients who had a first relapse in the cognitive behavior treatment group and were administered clonazepam had a second relapse. This occurred in 11 of the 18 patients of the clinical management group. The mean survival time was 266.5 weeks (SD=69.0) after the first relapse for the cognitive behavior treatment group and 217.3 weeks (SD=83.5) for the clinical management group. The difference was not significant. None of the six variables selected for survival analysis in the 26 patients who had a first relapse (using the second relapse as the event of interest) attained statistical significance. Patients who had a first relapse, regardless of treatment assignment, and who were given clonazepam (N=26) had a survival time of 232.5 weeks (SD=81.3). Such time was significantly longer (t=–9.84, df=25, p<0.001) compared to the survival time until first relapse in the same patients (mean=86.3, SD=73.0). After being given maintenance antidepressant treatment after the second relapse, four of the 11 patients in the clinical management group and none of the four in the cognitive behavior treatment group had a further relapse. One patient had four relapses during the 6-year follow-up.

The cognitive behavior treatment group had a total of 12 depressive episodes during the follow-up compared with 34 of the clinical management group (t=3.73, df=38, p<0.001).

Four patients of the 26 who had at least one relapse (15%) did not respond to the same antidepressant drug that was used in the first episode. This occurred in three patients taking desipramine (successfully switched to amitriptyline in one case, fluoxetine in another, and fluvoxamine in the third) and in one taking imipramine (the patient responded to fluvoxamine).

Discussion

This study has obvious limitations because of its preliminary nature. First, it involved a small number of patients in the evaluation of long-term effects. Second, it had a seminaturalistic design, since patients were treated with different types of antidepressant drugs and there was no placebo-controlled withdrawal of medication. Finally, treatment was provided by only one psychiatrist with extensive experience in affective disorders and cognitive behavior psychotherapy. The results might have been different with multiple, less experienced therapists. Nonetheless, the study provides new, important clinical insight regarding the treatment of recurrent, unipolar, major depressive disorder because of the long follow-up and its closeness to clinical practice.

Short-term cognitive behavior treatment after successful antidepressant therapy had a substantial effect on the rate of relapse after discontinuation of antidepressant drugs. Patients who received such treatment reported a substantially lower rate of relapse (40%) during the 6-year follow-up than the patients assigned to clinical management (90%). Such difference was significant, both in terms of comparison of mean survival time and survival analysis. This high relapse rate in the clinical management group is in line with the findings of Frank et al.

(7). Indeed, the ability of 10 sessions of psychotherapy to yield long-term benefits (more than half of the patients had no relapse during a 6-year period while being drug free) is impressive. Further, the group treated with cognitive behavior treatment had a significantly lower number of recurrences, when multiple relapses were taken into account.

Cognitive behavior treatment was found to be effective in decreasing the residual symptoms of depression

(3,

9). By deferring the psychotherapeutic intervention until after pharmacotherapy, we were able to provide a less intense course of therapy than is customary (e.g., 16–20 sessions) because psychotherapy could concentrate only on the symptoms that did not abate after pharmacotherapy. The fact that most of the residual symptoms of depression are also prodromal and that prodromal symptoms of relapse tend to mirror those of the initial episode provides explanation for the protective effect of this targeted treatment. Cognitive behavior treatment may act on those residual symptoms of major depression that progress to become prodromal symptoms of relapse

(17). This may particularly apply to anxiety and irritability, which are prominent in the prodromal phase of depression, may be covered by mood disturbances but are still present in the acute phase, and are again a prominent feature of its residual phase

(6). Indeed, substantial comorbidity concerned with anxiety disorders was found in both groups

(3). This led us to explore the feasibility of clonazepam administration after the first relapse and to continue treatment with it after the antidepressant drug was discontinued. The mean survival time after introduction of clonazepam was significantly longer than the one before the first relapse. However, the noncontrolled nature of the intervention hinders any conclusion.

This issue, however, is worthy of further research in view of three lines of evidence. First, long-term treatment with antidepressant drugs is not exempt from considerable problems

(18), in particular, the loss of clinical effect

(19). Indeed, also in our sample, there were instances of relapse despite antidepressant drug continuation after the second recurrence. The second line of evidence is based on the fact that in anxiety disorders, treatment of phobic disturbances was found to entail beneficial effects on the incidence of depression during long-term follow-up

(20,

21). Finally, coadministration of clonazepam and an SSRI was found to significantly improve short-term outcome in major depression

(22,

23), and clonazepam alone has mood-stabilizing effects

(24). Intermittent use of antidepressant medication, as endorsed by the protocol of this investigation, also presents some disadvantages

(25), such as resistance (when a patient, after a drug-free period, fails to respond to an antidepressant drug that yielded remission in a previous episode)

(26), as was found to occur also in this study.

Cognitive behavior treatment was not targeted to decreasing residual symptoms only. Two additional ingredients were added, in view of the clinical challenge represented by a patient population with recurrent depression. One was defined as lifestyle modification. Clinical experience has suggested in fact that recovered depressed patients are often unaware of the long-term consequences of a maladaptive lifestyle, which does not take chronic, minor life stress, interpersonal friction, excessive work (particularly in male professionals in their 40s) and inadequate rest into proper account. We postulated that both the presence of subsyndromal psychiatric symptoms

(6) and chronic stress exposure may cause an allostatic load, i.e., fluctuating and heightened neural or endocrine responses resulting from environmental challenge

(27). Further, it should also be noted that interventions that bring the person out of negative functioning are one form of success, but facilitating progression toward restoration of the positive is quite another

(28). Ryff and Singer

(28) suggested that the absence of well-being creates conditions of vulnerability to possible future adversities. A specific well-being-enhancing psychotherapeutic strategy

(8) was the third main ingredient of the cognitive behavior approach.

The study by Frank and colleagues

(7,

29) alerted the clinician to the need of providing maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Long-term, high-dose, antidepressant drugs appeared to be the treatment of choice. This preliminary investigation, using a similar patient population and a comparable follow-up, and other similar investigations

(1,

2,

4,

5) would challenge such stance while confirming the unfavorable long-term outcome of patients not receiving pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy. Long-term maintenance drug treatment

(7,

29) or psychotherapy

(30) may be necessary in several patients. However, a two-stage (cognitive behavior treatment after pharmacotherapy), sequential intensive approach may considerably affect the long-term outcome of patients with recurrent depression. The cognitive behavior intervention provided in this report was quite brief. It is conceivable, even though it has yet to be tested, that even better results might have been obtained with longer courses of cognitive behavior treatment and if patients beginning to experience signs and symptoms of relapse had received additional booster sessions of therapy.