Epidemiological data based on representative community samples are essential for the proper planning and prioritization of mental health services

(1) . This is particularly true for obsessive-compulsive disorder, which has been described as a hidden disease

(2,

3) because many sufferers are embarrassed and secretive about their symptoms and may not seek professional help. Sociodemographic factors, severity, and comorbid disorders may all influence treatment-seeking behaviors

(3) . Therefore, it is important to study the distribution and characteristics of the disorder beyond clinical settings

(4,

5) .

Currently, there is limited information on the epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid psychiatric disorders based on suitable standardized diagnostic instruments

(4), especially with random samples of the total population. The first National Comorbidity Survey

(6) did not include obsessive-compulsive disorder. Fourteen epidemiological studies that used the Present State Examination identified only one individual with the disorder because of the exam’s rigid hierarchical structure and exclusion criteria

(7) . The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study

(8) comprised individuals from only five sites in the United States; most epidemiological studies in other countries were also restricted to specific centers

(9) .

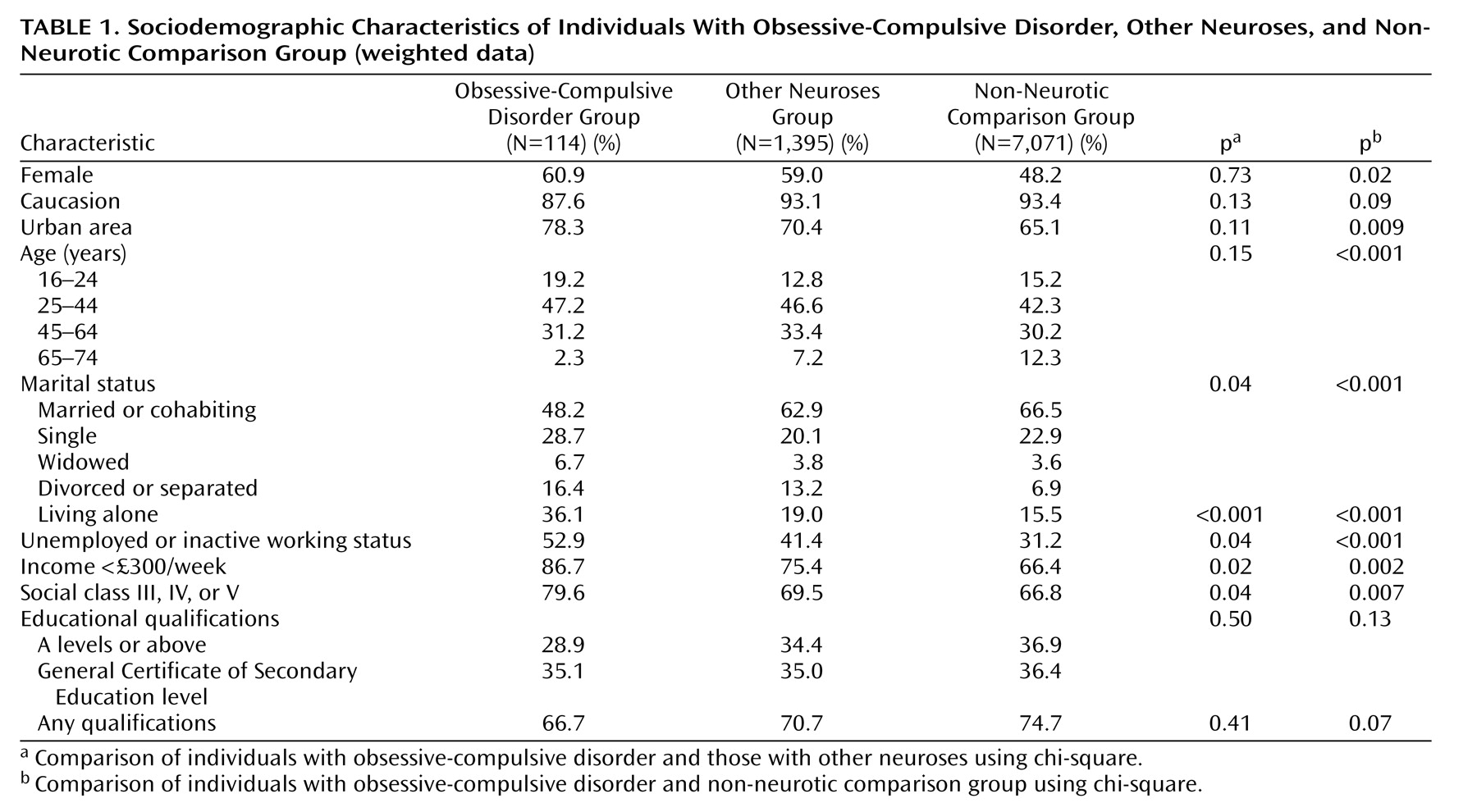

In this study, we sought to assess the prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid neuroses and alcohol and substance use in adults who participated in the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000. Sociodemographic factors, comorbidity, indicators of impairment, and help-seeking were compared between participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder, participants with other neurotic disorders, and a non-neurotic comparison group. To our knowledge, this is the first such analysis from a large national, representative survey.

We hypothesized that participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder would have a high prevalence of comorbid neurotic disorders, with a predominance of depressive episode, phobias, panic and generalized anxiety disorders among women and of substance use disorders among men. We expected those individuals with both obsessions and compulsions, with other co-occurring neuroses, and males to have more psychosocial impairment and to be receiving more treatment.

Discussion

In our community study, we analyzed data from a carefully conducted survey of a representative random sample of adults from all areas of Great Britain. The study does, however, have some limitations that must be highlighted. Only 114 participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder were identified, which lowered the power of some statistical analyses, especially those of subgroups of obsessive-compulsive disorder participants. The response rate of 69.5% suggests that the prevalence of the condition may have been underestimated, since those with obsessive-compulsive disorder might have been more likely to refuse. The use of lay interviewers and a fully structured clinical interview may, on the other hand, have led to overestimates of the presence and severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms

(2,

20) . The validity of the obsessive-compulsive disorder ICD-10 diagnosis, as generated by the Clinical Interview Schedule, has not been established. Although agreement about the diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder with the SCAN clinician semistructured assessment has been poor in general validations of the Clinical Interview Schedule, the numbers of obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals were inadequate to draw robust conclusions

(21) . Psychotic disorders were fully assessed in a second phase of the survey and only for a stratified subsample of participants. Only three participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder were thus identified as suffering from schizophrenia; since it could not be determined whether these were comorbid or misclassified and the numbers were too small substantially to affect our findings, these three participants were retained in the analysis. The study did not include eating and somatoform disorders. The cross-sectional design only provides information about the present state and does not allow inferences on lifetime psychopathology.

Our general findings are consistent with the available epidemiological data on obsessive-compulsive disorder

(7 –

9,

22) . The weighted prevalence of 1.1% is similar to most previous studies in different countries. Seven international studies using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule

(9) show annual prevalence ranging from 1.1% to 1.8%, and recent studies from Great Britain

(16), Canada

(2), and Chile

(22) report current prevalence varying from 1.1% to 1.3%.

The data presented in this study are also in agreement with most epidemiological studies pointing to a predominance of obsessive-compulsive disorder in lower age groups

(8) and in women

(7,

9) . In the previous British survey

(16), obsessive-compulsive disorder was diagnosed in 1.5% of women and 1.0% of men. An equal prevalence in both sexes was found in the Edmonton study

(23), while summarized data from international studies

(9) showed a female/male ratio varying from 1.2 to 1.8. Our findings also reinforce the predominance of individuals with pure obsessions in the community

(8,

9,

23) . By contrast, in clinical samples, the sex ratio tends to be equal

(24), and the majority of individuals have both obsessions and compulsions

(4) . This may reflect differences in assessment methods or in the types of individuals that reach health care; presumably, women and the purely obsessive individuals are less likely to seek treatment

(4) .

Our data do not confirm the reported rarity of obsessive-compulsive disorder in ethnic minority groups in the community

(4,

7,

8) but are in line with those that show similar educational qualifications

(4) and lower rates of marriage

(8) .

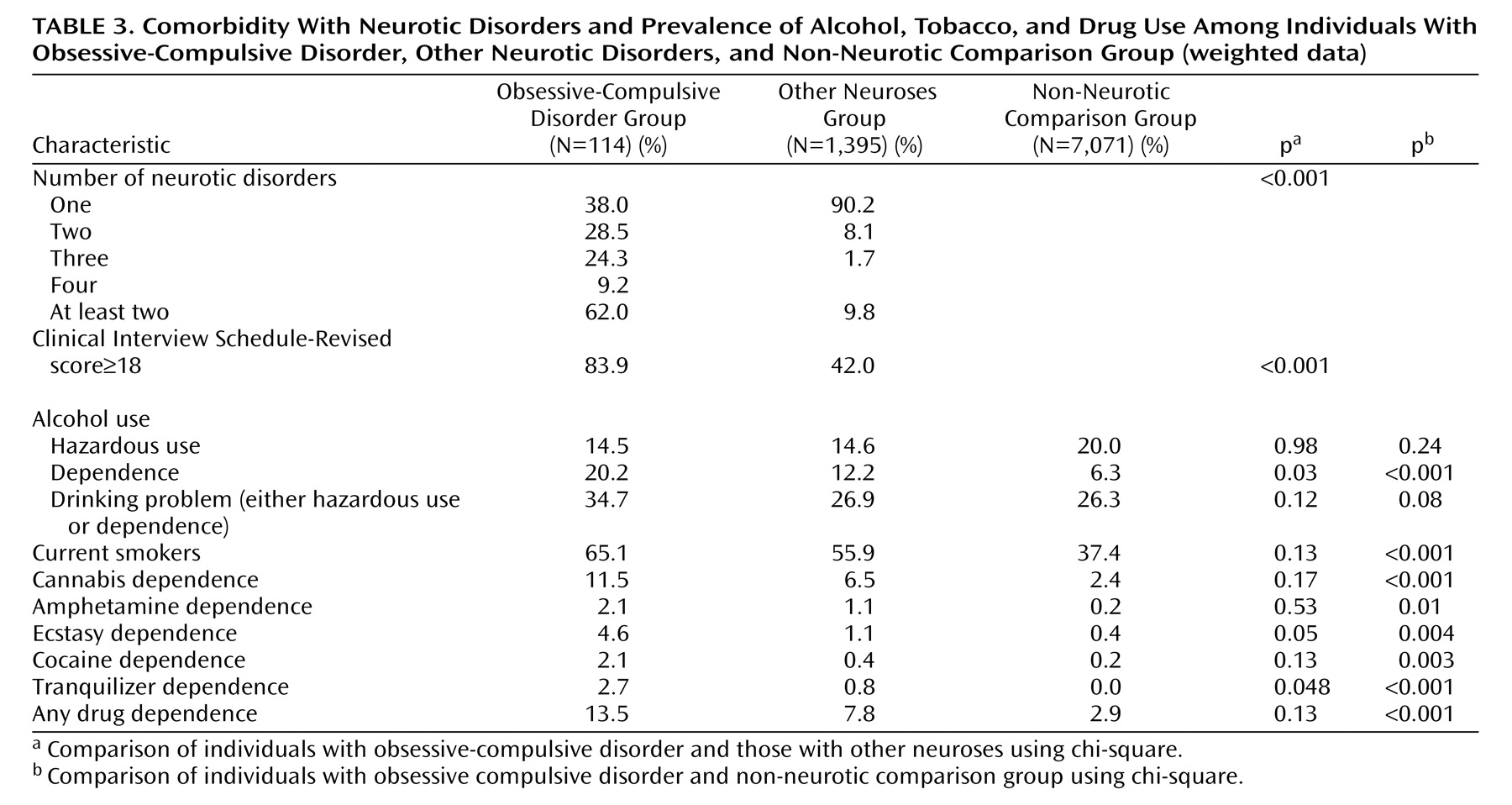

Obsessive-compulsive disorder participants had relatively high rates of comorbidity, a finding that is in accordance with most data from both community

(8,

16,

23) and clinical settings

(25,

26) . While our comparison was of necessity skewed (those with obsessive-compulsive disorder and one or more other neurotic disorders were counted only once as being comorbid obsessive-compulsive but not as comorbid with other neurosis), this could not have accounted for more than a small part of the large difference in comorbidity between those with obsessive-compulsive disorder and those with other neuroses. The most frequent comorbid condition was depressive episode, followed by anxiety disorders

(25 –

29) . Direct comparison with other studies is complicated, since most are from clinical settings and several use different diagnostic categories. However, our findings are in the reported range for depressive episode (20%–67%), simple phobia (7%–22%), social phobia (8%–42%), and generalized anxiety disorder (8%–32%)

(24 –

26,

28,

30 –

33) . The 34% prevalence of problem drinking (hazardous drinking or dependence) among obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals is similar to the 36% described in Canada

(23) but higher than the 24% found in the Epidemiological Catchment Area Study

(8) . This higher rate may be because of measurement or cultural differences, since the prevalence of problem drinking in our non-neurotic comparison group was as high as 26%. Dependence may be a specific problem for obsessive-compulsive disorder sufferers, since they differed in this aspect (but not in hazardous drinking) from the other two groups. The lower rates of alcohol dependence (approximately 10%) described in clinical samples

(34 –

36) may suggest that individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder and alcohol dependence are either less likely to seek treatment or are being treated for their alcohol problem, with their obsessive-compulsive disorder going unrecognized

(37) . More obsessive-compulsive disorder participants were current smokers (65%) than non-neurotic individuals (37%), contradicting previous reports of low rate tobacco use

(29,

38) . Interestingly, pure obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals had significantly higher rates of dependence on drugs (particularly on cannabis) than comorbid individuals, lending support to the notion that some sufferers may use substances as an attempt to deal with the distress caused by the obsessions or compulsions rather than seeking professional attention

(8,

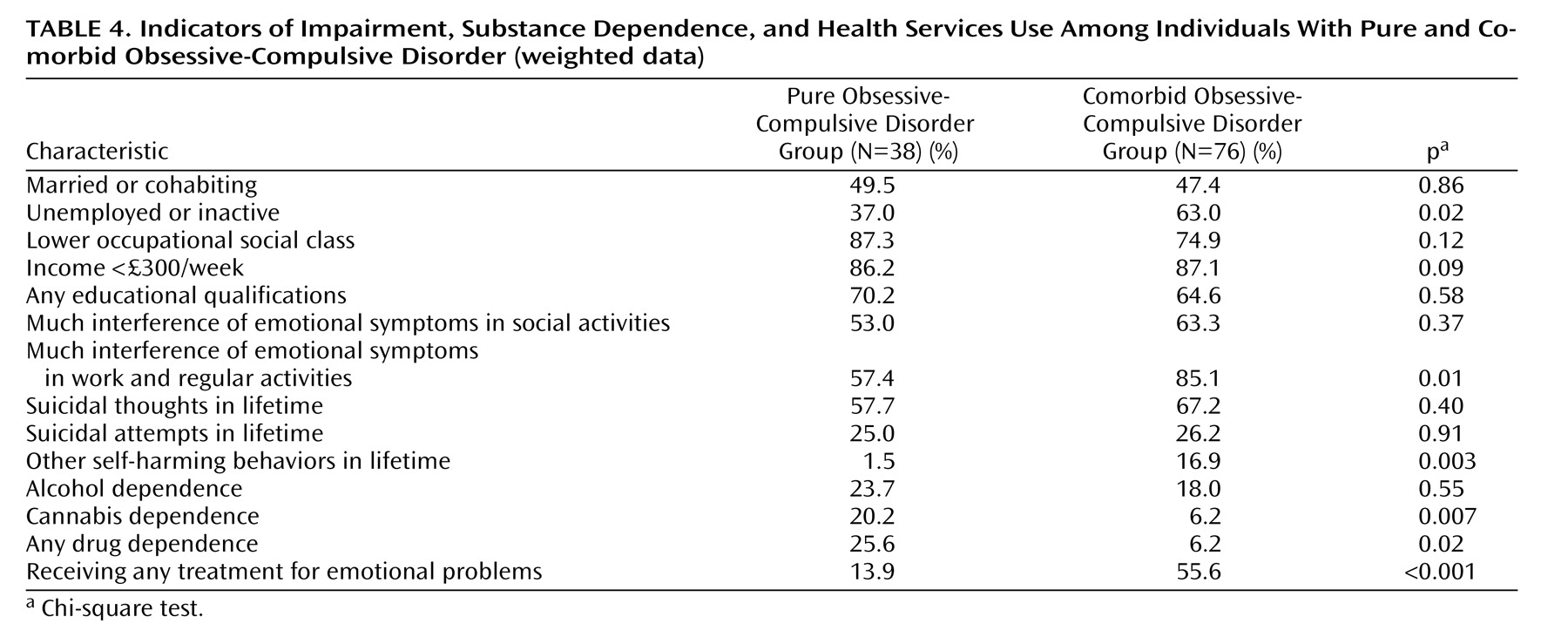

23) . As expected, both alcohol hazardous use and dependence were significantly more common in men

(32), and all kinds of drug dependence were more frequent in men, although many of the differences did not reach statistical significance.

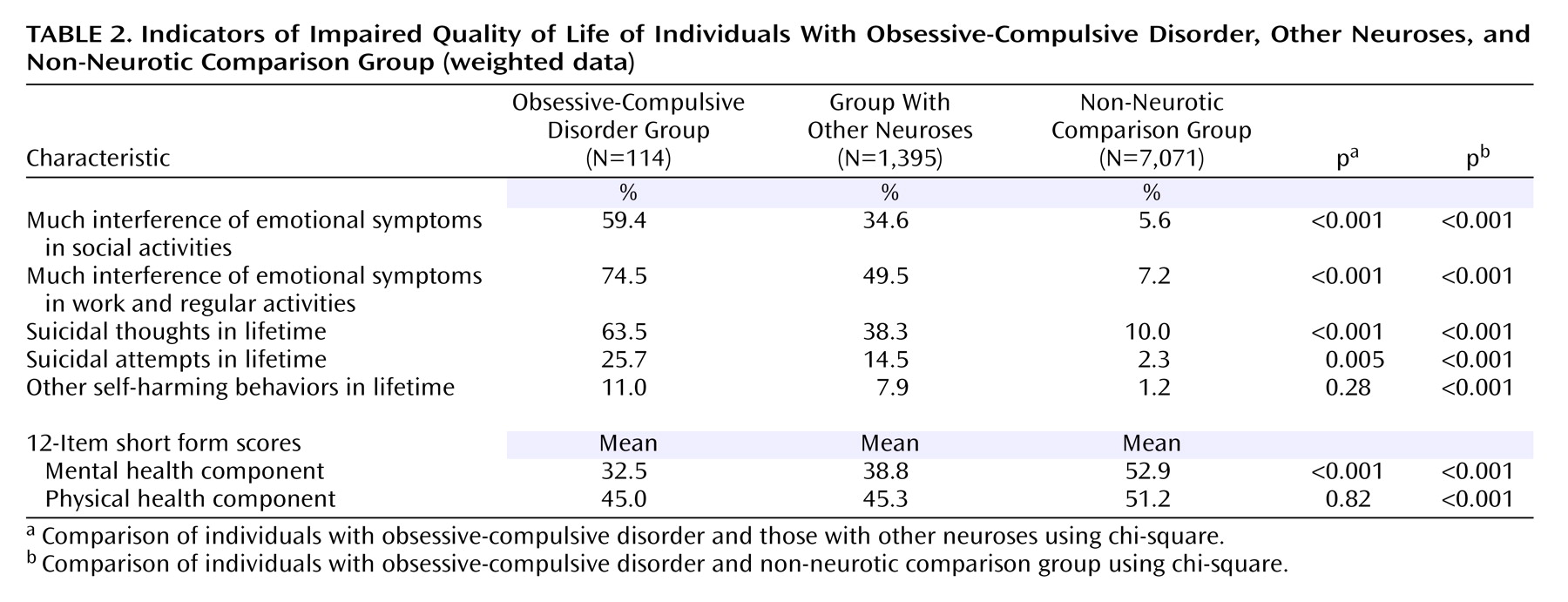

Our analysis highlights the public health significance of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although it is a relatively rare condition, it is associated with a very high degree of impairment. Individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder stand out not only from those who are mentally well but also from those with other neurotic conditions. With respect to those individuals with other neuroses, individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder are less likely to be married, more likely to be unemployed, more likely to have very low income levels, and more likely to have low occupational status. They are also more likely to report impaired social and occupational functioning. These differences are largely independent of the extent of non-obsessive-compulsive-disorder-related psychological morbidity, suggesting an intrinsic effect of obsessive and compulsive symptoms. An important finding in our study is that 26% of the obsessive-compulsive disorder participants reported at least one suicidal attempt in their lifetime, nearly double the proportion among those with other neuroses, and 10 times that of non-neurotic comparison individuals. Historically, and perhaps erroneously, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder have been considered at low risk for suicide

(39,

40), with the exception of a few studies

(33,

41) . Our data suggest that obsessive-compulsive disorder does not fit conveniently into the fashionable relabeling of neurosis as “common mental disorder” and psychosis as “severe mental illness.” Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a neurosis that is both rare and severe and should be prioritized accordingly.

Encouragingly, perhaps because of the chronicity and severity of the disorder, rates of help-seeking and engagement with treatment are relatively high among obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals overall. However, even with similar degrees of psychosocial impairment and suicidal risk and more drug dependency, pure obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals are receiving much less treatment than those with comorbidity (14% versus 56%). This is a clear indication of unmet need and a cause for concern. More research is warranted to identify the barriers to seeking and receiving help in this subgroup. These may include the egodystonic nature of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms and the low level of public awareness about the existence or nature of the condition, compared, for example, with that which exists for depression, phobia, or psychosis. An appropriate public health response may need to combine public education with training of professionals, particularly primary health care workers.