Investigation of mortality risk among offspring of mentally ill people has been conducted since the 1930s

(1) . Earlier studies generally reported no evidence for higher risk in offspring of affected parents

(2 –

4), whereas most studies since the 1960s have indicated greater risk of fetal, perinatal, and infant mortality associated with parental schizophrenia

(5,

6), specifically maternal schizophrenia

(7 –

9) and the broader range of maternal psychoses

(10) . The best available evidence to date has come from large register-based studies conducted in Denmark

(8), Sweden

(9), and Australia

(11), although the latter recently found no evidence of higher offspring mortality risk. The two Scandinavian studies reported elevated relative risks associated with maternal schizophrenia of approximately twofold for stillbirth and between two- and threefold for infant death. The Danish study

(8) additionally found a fivefold relative risk for sudden infant death syndrome. An elevated risk of sudden infant death syndrome associated with postnatal depression

(12,

13) and maternal substance misuse

(14,

15) has also been indicated. Evidence is, however, currently lacking for mortality risk among these offspring beyond infancy and for effects of paternal versus maternal disorder

(1) .

Higher mortality risks may be linked to inadequate antenatal care

(16), restricted fetal growth

(17), obstetric complications

(18,

19), medication toxicity

(20), adverse social environment

(21,

22), and genetic inheritance

(23) . The relative importance of these putative mechanisms is likely to vary with the age of the child, parental diagnosis, and which parent is affected. It seems intuitive to expect that effects of maternal disorders are stronger, especially during the perinatal period and infancy. Maternal schizophrenia may be associated with particularly high risk because of the enduring and debilitating nature of the disorder and because parenting outcomes have been shown to be poor in these mothers compared with those admitted with affective disorders

(24) .

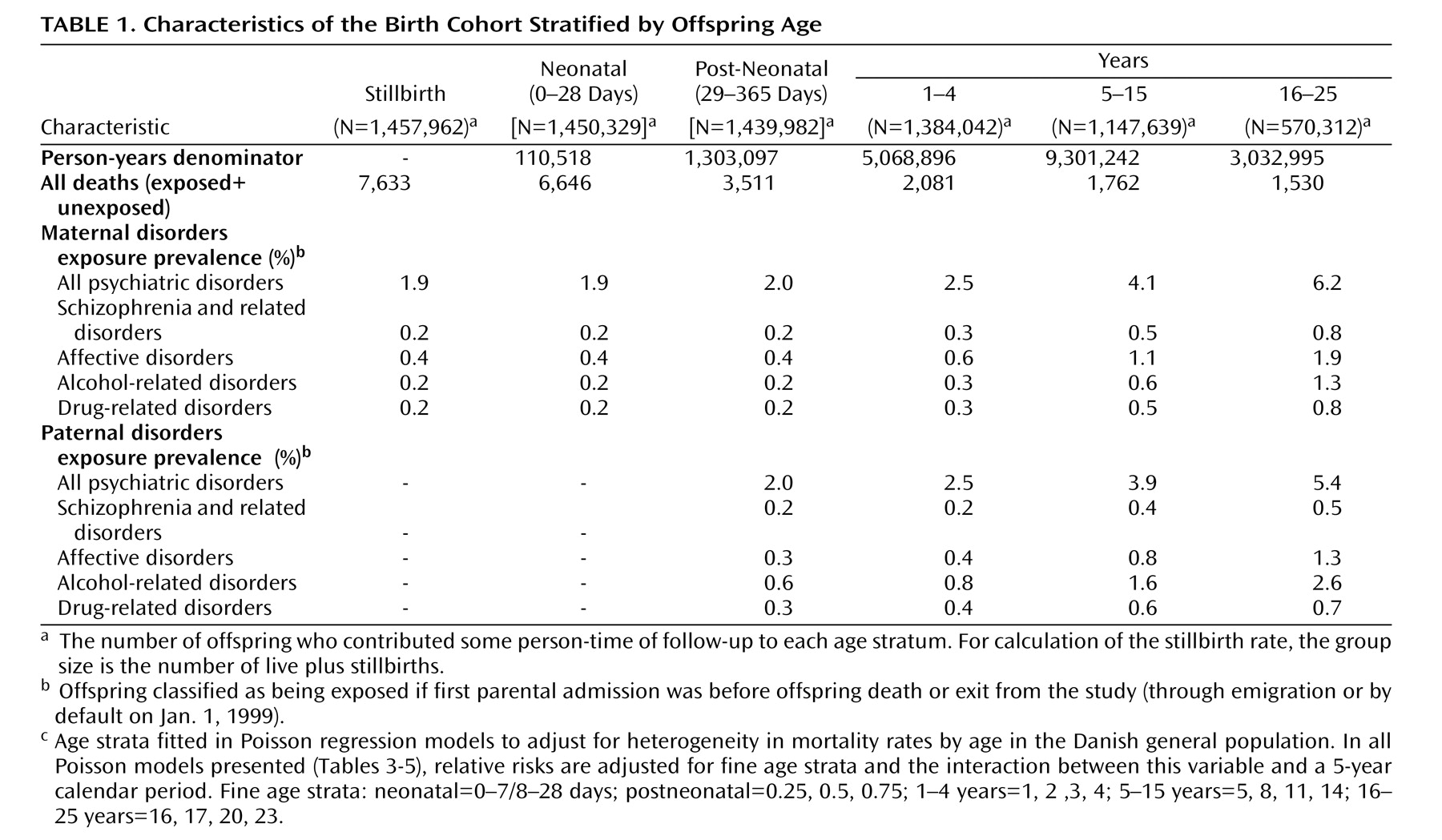

The objectives of our investigation were 1) to conduct a population-based follow-up study of all-cause mortality risk in offspring of mentally ill people from birth through early adulthood; 2) to investigate different parental diagnostic groups (i.e., schizophrenia and related disorders, affective disorders, alcohol and drug-related disorders), and 3) to compare relative risks for maternal versus paternal disorder and by number of affected parents.

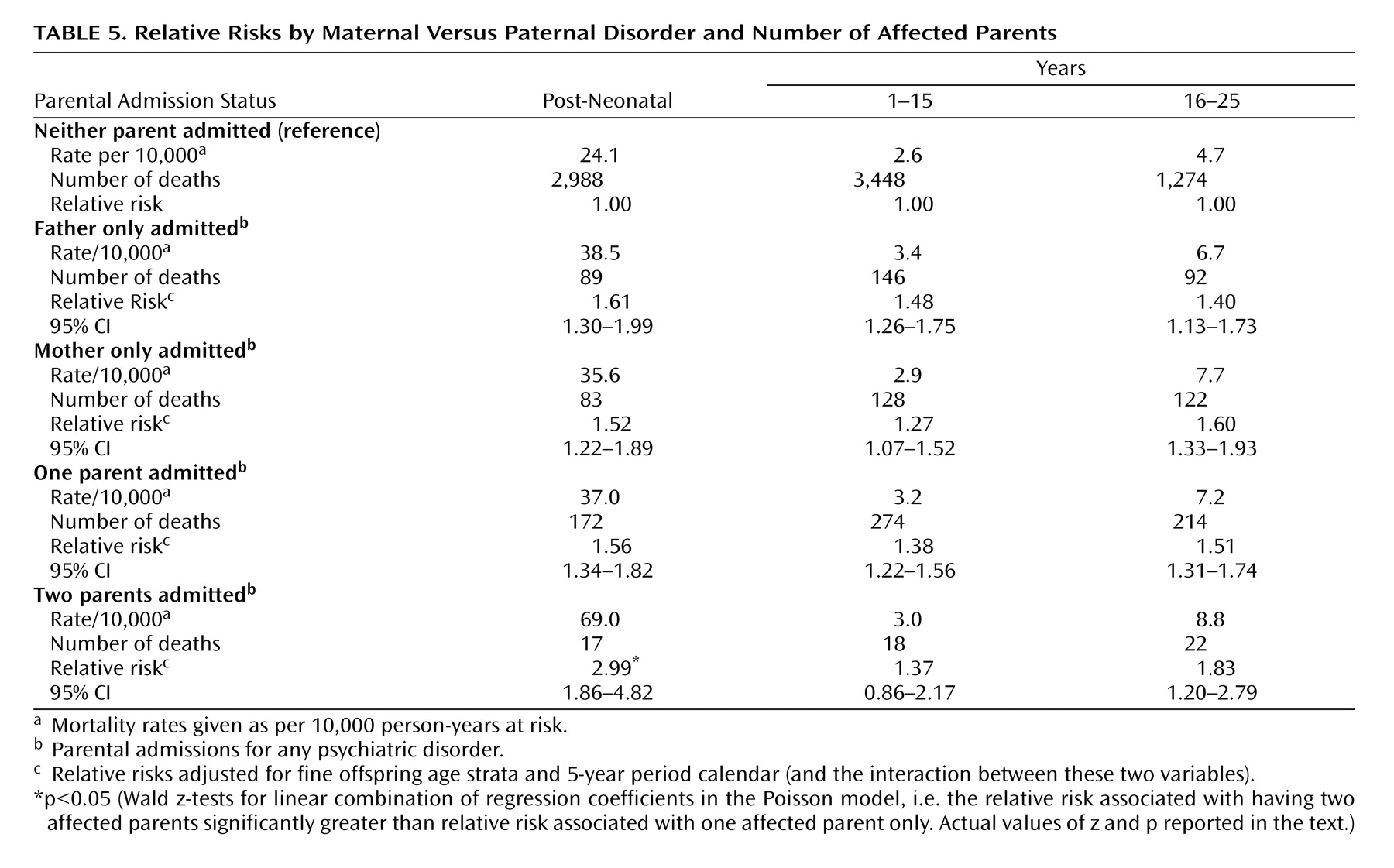

We hypothesized that 1) offspring of mothers and fathers admitted with some type of psychiatric diagnosis would be at greater risk of mortality at all ages compared with the general population; 2) relative risks would be greater for perinatal and infant mortality versus death at age 1 year and over, for maternal versus paternal disorders, and for two versus one affected parent; and 3) relative risks would be especially high among offspring of parents with schizophrenia and related disorders compared with those whose parents had other types of psychiatric disorder.

Discussion

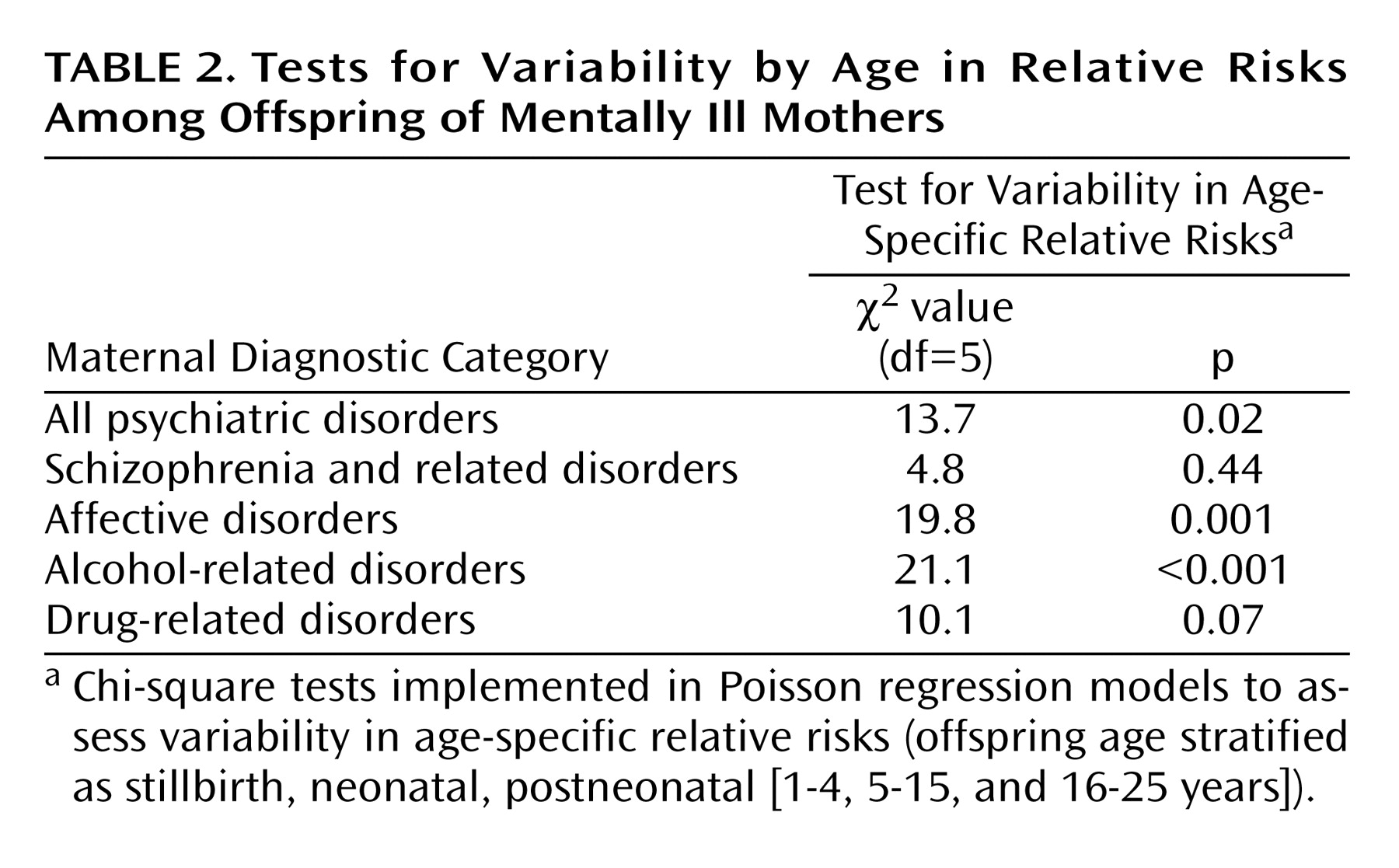

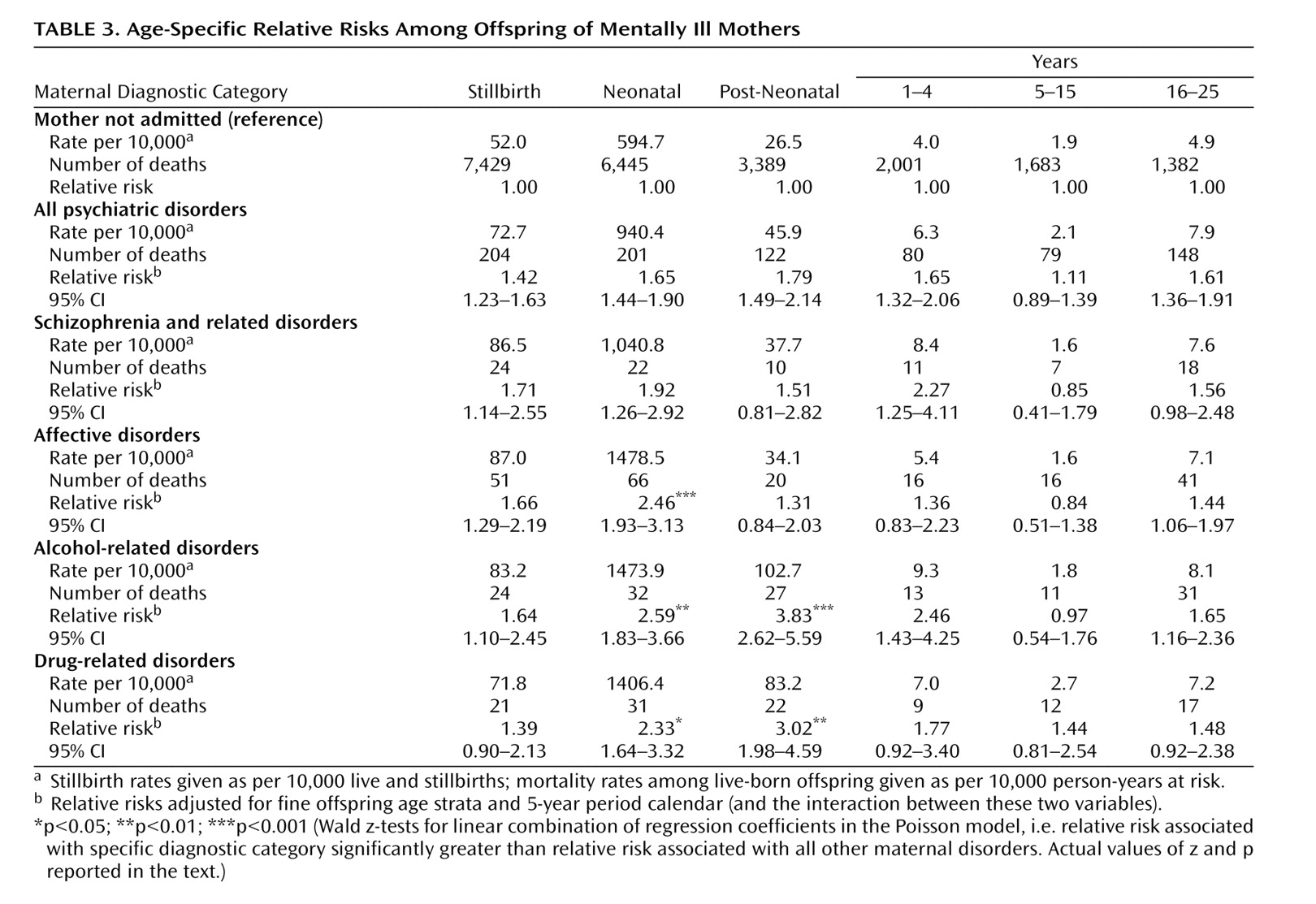

Some of these findings confirmed our prior hypotheses. First, significantly raised mortality risks in offspring of mothers admitted for any type of psychiatric diagnosis were observed from birth through early adulthood, although relative risks were attenuated at ages 5–15 years. Second, relative risks associated with maternal illness varied significantly by age and were generally greatest in the first year of life, during the neonatal (early and late) and postneonatal periods. Relative risks for stillbirth were, however, somewhat lower. Third, the relative risk of postneonatal death among offspring with two mentally ill parents was significantly higher than that associated with having only one affected parent.

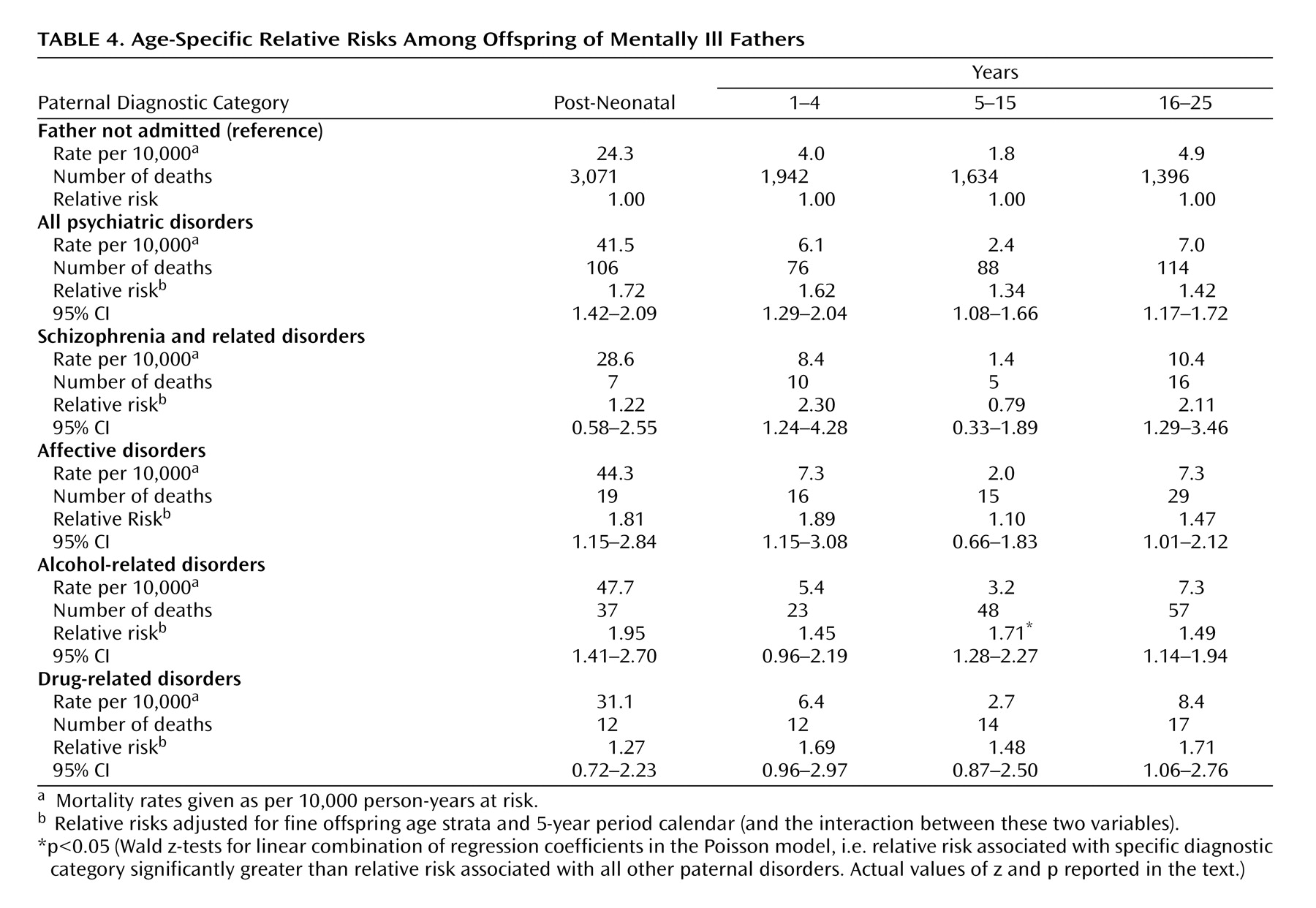

However, some findings were contrary to expectation. First, from the postneonatal period onward, similar effect sizes were observed for maternal verus paternal disorder in general. Second, we identified several high-risk subgroups that had relative risks higher than those associated with other psychiatric disorders, but these did not include offspring of parents with schizophrenia and related disorders. Compared with all other maternal disorders, relative risks were significantly raised among neonates and postneonates whose mothers had alcohol and drug-related disorders and among neonates whose mothers had affective disorders. The latter was a particularly surprising result.

This is the first large population-based investigation of mortality risk among offspring of mentally ill parents with follow-up through early adulthood. The effects of a broader range of parental disorders were assessed in previous studies, and derivation of time-dependent exposure variables enabled comparison of associations with specific diagnostic groups versus parental psychopathology in general. Comparisons of effects associated with maternal versus paternal disorders, and of having two versus one affected parent, were performed with a much larger study group than previously available

(5,

6) .

Since Denmark has no privately funded psychiatric inpatient services, the national register provides a near complete population-based record of admissions since 1969. Selection biases, however, do exist because the majority of mentally ill people are never admitted. The degree of bias is likely to vary by diagnostic category. Bennedsen et al.

(8) argue that most people with schizophrenia are probably admitted at least once. Thus, even though the register may not capture all cases of schizophrenia and related disorders that occur in the population, the group identified would have good external validity

(37) . Selection bias is likely to be higher for investigation of parental affective and substance-related disorders because most of these people are not admitted. For these categories, the observed results are applicable only to the severe end of the diagnostic spectrum. Currently, there are no registers available in Denmark or elsewhere to undertake population-based studies of illnesses that are usually treated in the community. In terms of diagnostic validity, Munk-Jørgensen

(38) reported a high positive predictive value of 90% for ICD-8 diagnosis of schizophrenia. Kessing reported good validity for ICD-10 diagnoses of affective disorders

(39) and continuity between 8th and 10th ICD revisions for these disorders

(40) . There have been no diagnostic validation studies of alcohol or drug-related disorders in the Danish psychiatric register.

Our study has several limitations. First, although a large birth cohort was investigated, the rarity of death among exposed offspring led to sparse data in certain subgroups. This, for example, precluded estimation of relative risks among offspring of two parents affected with specific diagnoses. Second, relative risks of stillbirth and neonatal death associated with paternal disorders were not estimable without substantial bias because of missing data for paternal identity. Third, as in many open cohort studies, bias due to left censoring is likely. Parental psychiatric admission histories were unavailable prior to April 1, 1969, when the psychiatric register was computerized. Thus, misclassification of exposure status because of previous unregistered parental admissions could especially bias effect estimates for births occurring in the earlier years of the cohort. However, this is likely to have attenuated the observed relative risks so that the associations we report are not spurious, and the effect size estimates are conservative.

Finally, we were unable to adjust for potentially important confounders, such as antenatal care attendance, smoking, substance misuse without inpatient admission, and socioeconomic status. Other investigators were also unable to adjust for these factors in recent register-based studies

(8,

11) . Nilsson et al.

(9) did account for maternal smoking and educational status, but their adjusted relative risks for stillbirth and infant death associated with maternal schizophrenia remained significantly elevated. It seems intuitive to assume that the confounding effects of these factors are greater in relation to maternal (versus paternal) disorder and for stillbirths and infant deaths compared with mortality beyond the first year. Controlling for factors such as low antenatal attendance, substance misuse, and smoking during pregnancy could also lead to overadjustment, since these measured exposures are likely to occur as a consequence of maternal psychiatric illness.

Our data overlap considerably with those used in a previous study

(8) investigating rates of stillbirth and infant death among all women diagnosed with schizophrenia who gave birth during 1973–1993. We extended the birth cohort up to 1998, investigated other maternal conditions as well as paternal disorders, and assessed mortality outcomes beyond infancy through early adulthood. To avoid potential reverse causality bias, we also used a more stringent definition of exposure to include only maternal first admissions that occurred prior to an offspring death. Where comparison is possible, i.e., risk of stillbirth and infant mortality associated with maternal schizophrenia, our findings are consistent with those reported from Sweden

(9), but not with those from a recent Australian study

(11) . These investigators found no evidence of higher risk of stillbirth, infant mortality, or early childhood mortality in offspring of mothers with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or unipolar disorder. Type II error seems an unlikely explanation for their negative finding, since the odds ratios reported were generally close to unity. Substantive differences between study populations, or between health and social care systems, may explain the incongruous findings. Our results are, however, consistent with those of most studies published since the 1960s, which have generally shown raised mortality risks among the offspring of mentally ill parents

(1) .

Relative risks vary according to age. Offspring of mentally ill parents are at higher risk of death during infancy and the years prior to attending school, and relative risks rise again in early adulthood. It may be that during schooling years these children are partially protected from the environmental hazards that are apparently associated with parental mental illness. Relative risks also vary by diagnostic category. Clinicians should be mindful of the high-risk subgroups identified as well as our finding that schizophrenia and related disorders are not associated with excess mortality risks relative to other parental disorders. The greatest number of excess deaths were attributable to alcohol-related disorders, this being the most prevalent paternal diagnostic group and the second most prevalent in mothers.

Identification and interpretation of etiological mechanisms must await investigation of cause-specific mortality, which was the objective of our current investigations. Future studies should investigate the impact of parental conditions that are generally treated in community settings and estimate unbiased relative risks of perinatal mortality associated with paternal disorder.