Depression is common, affecting about one in five people during their lifetime

(1 –

3) . Severe depression is also a major risk factor for suicide, and up to 15% of those hospitalized for depression eventually commit suicide

(4) . Most patients who commit suicide suffer from a psychiatric illness, with advancing age, male gender, and medical illness among important predisposing factors

(4,

5) . As the cause of death for approximately 1 million people worldwide each year, suicide can be a devastating event with a complex etiology, and a better understanding of contributing factors is essential to suicide prevention

(6 –

8) .

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have become increasingly popular for the treatment of depression

(9) . These drugs are well tolerated by most patients, are safer in overdose than traditional antidepressants, and their availability has encouraged antidepressant prescribing in primary care

(9,

10) . Several anecdotal reports describe the emergence of intense suicidality during the initial period of SSRI therapy

(11 –

16), but it is difficult to separate the role of depression from a possible adverse effect of treatment.

The potential association between SSRI antidepressants and suicide has garnered considerable media attention

(17), prompting multiple editorials

(18 –

21), litigation against the pharmaceutical industry

(22), allegations of corporate malfeasance

(23,

24), and national public health advisories

(25) . Industry-sponsored studies, single case reports, meta-analyses, and practice-based epidemiologic studies have yielded variable findings regarding the association between SSRI antidepressants and suicide

(26 –

37) . Moreover, the exclusion of actively suicidal patients from clinical trials of antidepressants renders pooled analyses underpowered to detect differences in mortality, as illustrated by the recent findings of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

(25,

32,

38) .

Recent attention has focused on the possible risks of antidepressant treatment in children, yet most cases of SSRI-induced suicidality have been reported in adults

(14,

15,

39) . No studies have addressed the risk in older patients, despite the high frequency with which antidepressants are used in this population

(9,

40) . In this study, we linked population-based prescription records and coroner’s data to explore the association between the initiation of antidepressant therapy and subsequent risk of suicide in a population of more than 1.2 million elderly patients.

Method

Setting

We conducted a population-based study in Ontario. Ontario is Canada’s largest province, with a population of 11,100,876 at the midpoint of the study period, which included 1,264,686 who were 66 years of age or older. All Ontario residents 65 years and older had universal access to health insurance for prescription drug coverage, physicians’ services, and hospital care. The study was approved by the Chief Coroner for Ontario and the research ethics board of Sunnybrook and Women’s College Health Sciences Centre.

Subjects

Using records from the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario, we identified consecutive cases of suicide among Ontario residents aged 66 years and older that occurred over a 9-year period (Jan. 1, 1992, to Dec. 31, 2000). We did not examine the first year of eligibility for prescription drug benefits (age 65) to avoid incomplete medication records, and we excluded patients younger than 65 because prescription records were not available for analysis. The date of suicide served as the index date for all analyses.

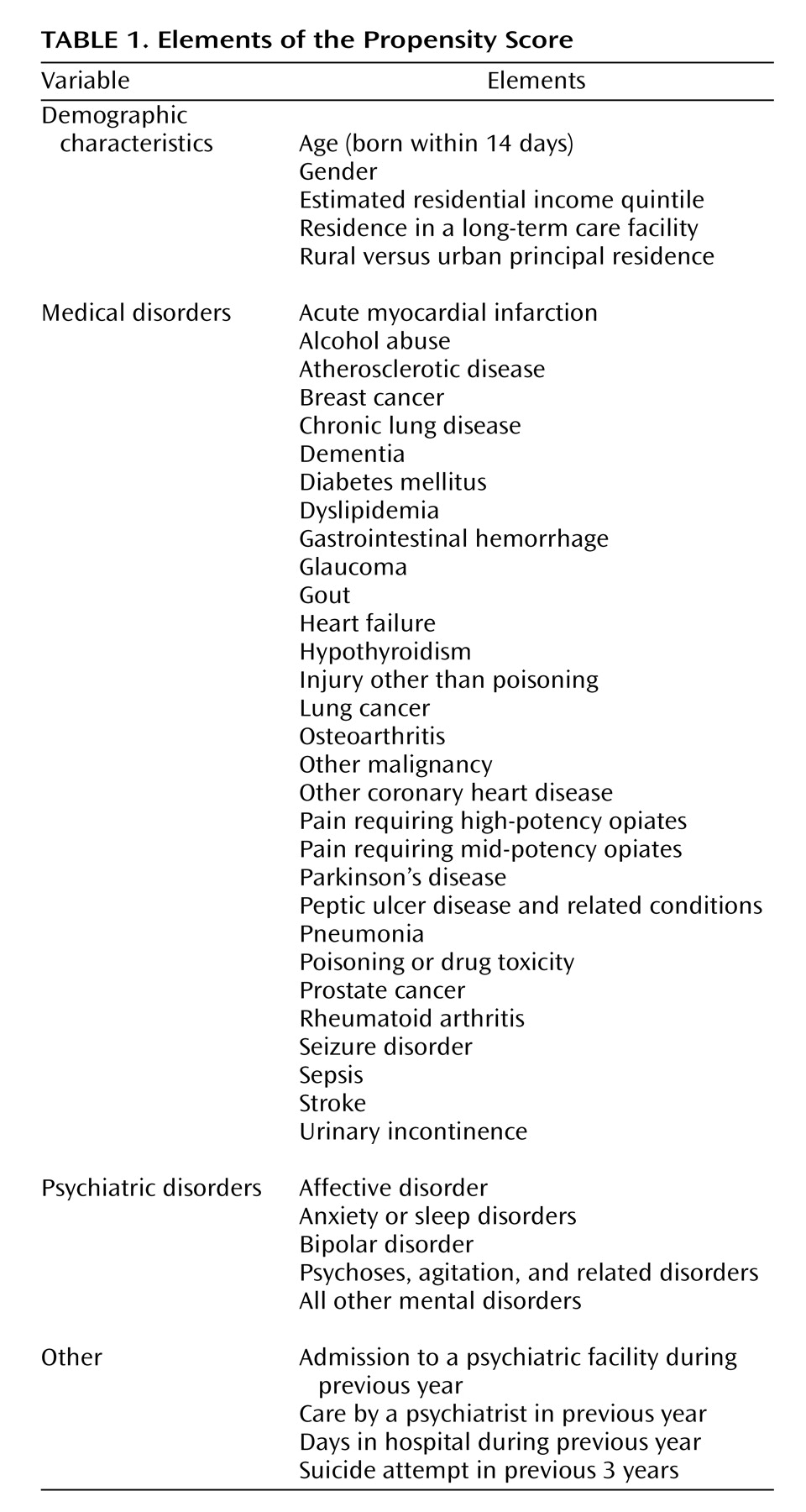

Propensity score methods were used to select comparison patients from the general population

(41,

42) . This is an advanced matching technique that involves modeling a large amount of information on each subject to minimize differences between suicide and comparison groups. This included demographic data as well as clinical information regarding specific medical and psychiatric conditions, collectively identified from hospital admission records, physician diagnosis claims, and outpatient prescription claims. A complete list of the various elements of the propensity score is shown in

Table 1 .

A structured, iterative process similar to that described by Rosenbaum and Rubin

(43) was used to construct a propensity score for each individual that predicted suicide outcome by balancing all characteristics shown in

Table 1 between the suicide cases and comparison subjects. To account for changing patterns of antidepressant use in Ontario over the study period

(9), propensity scores were calculated for all possible comparison patients for each case at every index date. Once the final propensity score model was developed and scores calculated for all potential comparison subjects, we identified all eligible comparison patients for each case using calipers of 0.2 standard deviations of the propensity score. From these we randomly selected four comparison subjects for each suicide case. Suicide cases whose propensity scores were too high to permit a match to four comparison subjects were retained for descriptive purposes but excluded from the matched analyses.

Exposure to Antidepressants

We examined prescription records of suicide cases and comparison subjects through the Ontario Drug Benefit program database. The Ontario Drug Benefit program collects detailed records of prescriptions dispensed to all elderly residents of Ontario, contains little (<1%) missing data, and is regularly used to analyze medication use in the community

(44 –

47) . SSRI antidepressants included fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, and citalopram. Other antidepressants included secondary amine cyclic antidepressants (desipramine, nortriptyline, protriptyline, maprotiline, and amoxapine), tertiary amine cyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, imipramine, doxepin, trimipramine, and clomipramine), and miscellaneous antidepressants (venlafaxine, trazodone, bupropion, and nefazodone). We did not examine monoamine oxidase inhibitors given their infrequent use, and we did not study mirtazapine because it was not an insured benefit during most of the study period.

In all main analyses, new use of an antidepressant was defined as no previous prescription for a drug from the same class in the previous 6 months. In a secondary analysis, we defined new use as no prescription for any other antidepressant in the preceding 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

Databases were linked in an anonymous fashion using an encrypted version of each patient’s health card number. The primary analysis used conditional logistic regression to estimate the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) for suicide associated with new use of an antidepressant at discrete monthly intervals from the start of treatment.

Multivariable analysis adjusted for rural place of residence (imputed from home postal code)

(48), estimated residential income quintile, previous suicide attempt, the number of prescription medications dispensed in the previous year

(49), and any evidence (from prescription records, physician diagnosis codes, or hospital discharge records during the preceding year) of alcohol abuse, malignancy, anxiety or sleep disorder, bipolar disorder, depression or other mood disorder, agitation or psychosis, poisoning or other injury, provision of care by a psychiatrist, or admission to a psychiatric facility. All tests of significance used a two-tailed p value of 0.05 for statistical significance and were conducted using SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.)

Discussion

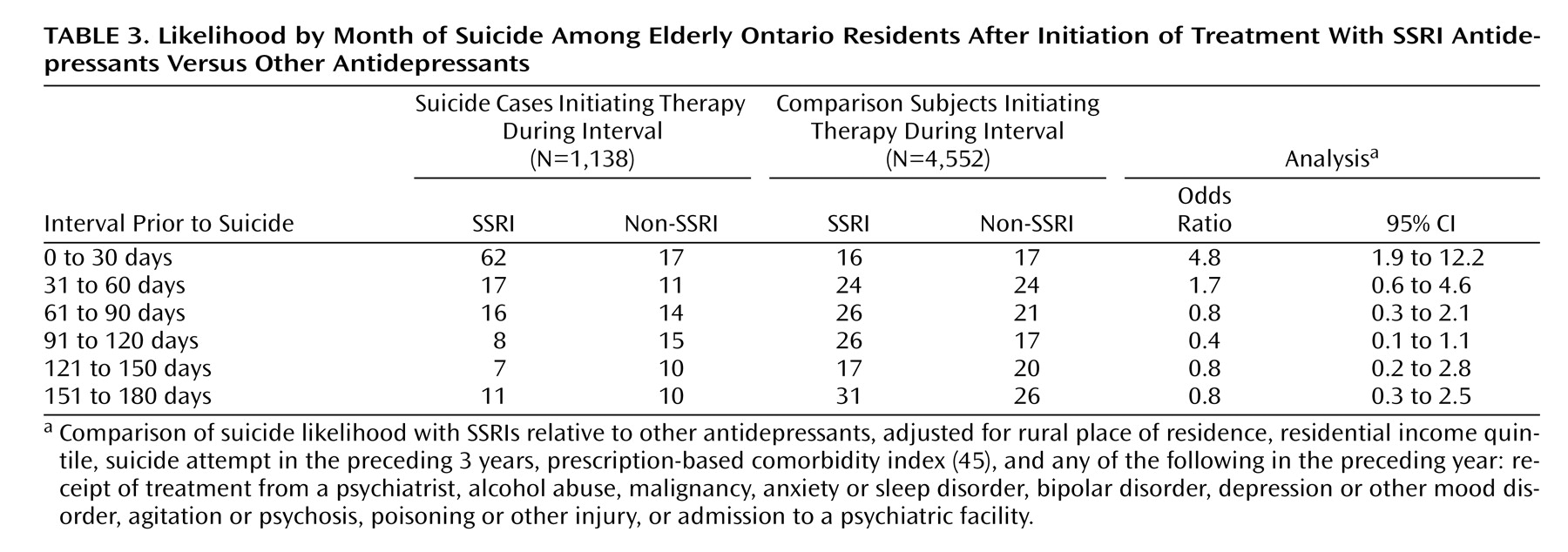

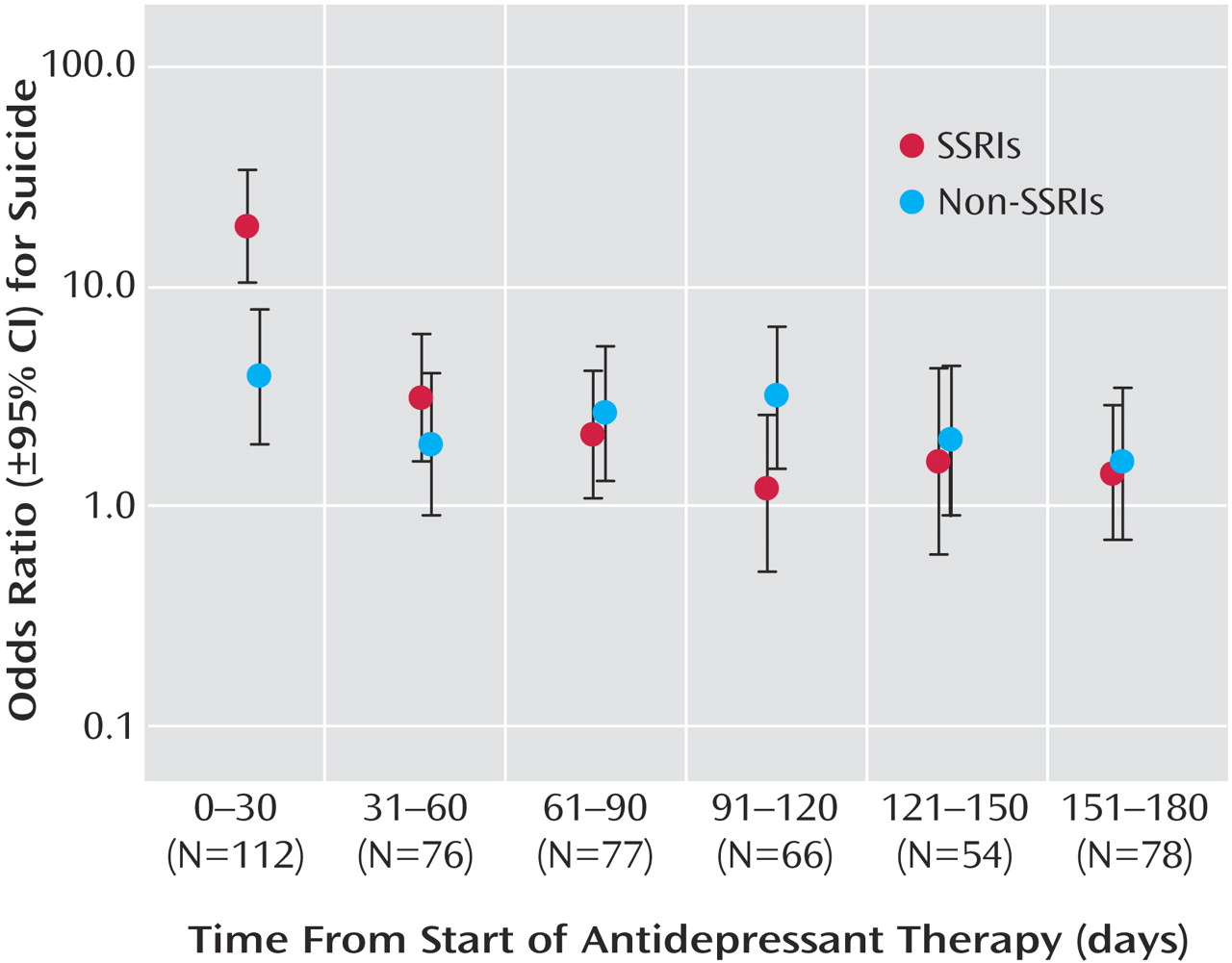

Previous research on SSRI antidepressants and suicide has been limited by an absence of suitable controls, small study group sizes, use of surrogate endpoints, inefficient study designs, and a lack of population-based data

(15,

26,

31,

32, 38, 52, 56–59). Using 9 years of comprehensive coroner’s records and prescription data in a population of more than 1 million older patients, we found a substantial increase in the relative risk of suicide following the initiation of SSRI treatment. The differential risk compared with other antidepressants was confined to the initial month of therapy, after which time no heightened risk was evident. It is interesting that we found SSRI antidepressants to be not associated with an increased suicide risk among women; however, as with all post-hoc analyses, this observation may be due to chance and should be interpreted cautiously.

Although case/control studies cannot generally yield estimates of excess risk, the population-based nature of our data indicates that the absolute risk of suicide during initial treatment with SSRI antidepressants is very low. In contrast, more than two-thirds of cases committed suicide while not receiving an antidepressant, highlighting the undertreatment of depression in older patients

(60,

61) .

Several mechanisms may underlie the association between SSRI antidepressants and suicide

(18,

19) . During initial therapy, the risk of suicide may increase as some aspects of depression resolve (e.g., psychomotor retardation), thereby energizing the patient to suicide

(62) . Patients may also develop akathisia-like symptoms during treatment with SSRI antidepressants, which may increase the risk of suicide (4, 14, 63–65). In addition, emerging evidence suggests that genetic differences in drug metabolism or serotonin receptor polymorphisms influence the safety and tolerability of these drugs (66, 66–69). Our findings mirror the clinical observation that the vast majority of patients treated with SSRI antidepressants do not attempt suicide, but that in rare instances these drugs appear to incite suicidal ideation during the first weeks of therapy (39, 70, 71). We speculate that treatment-emergent agitation or dysphoria can provoke suicidal ideation in some patients (72). Like other rare adverse drug events, this idiosyncratic response may have a pharmacogenetic basis (73–76), and future research may provide a means of identifying such individuals before commencing treatment (77, 78).

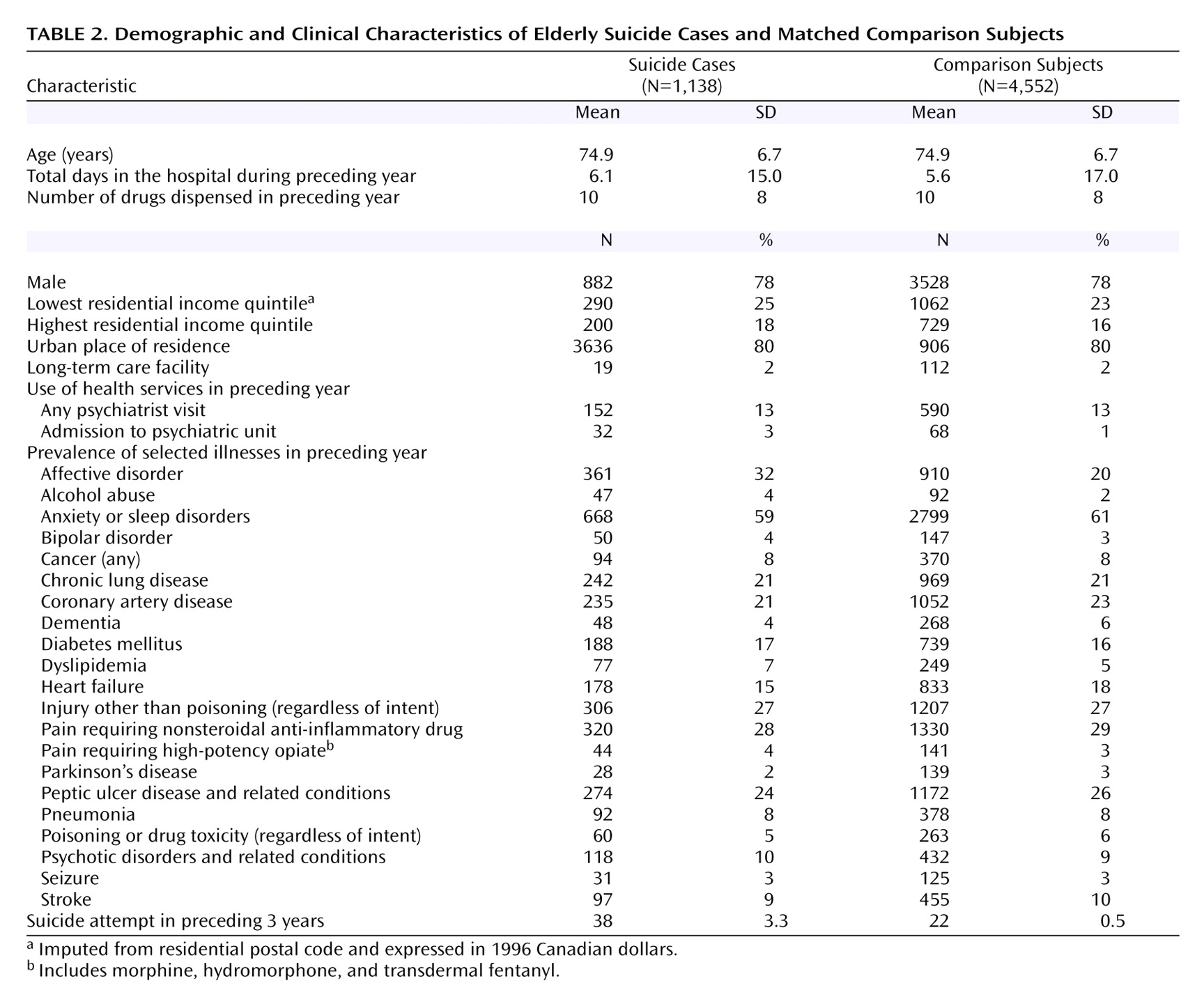

An alternative explanation for our findings might be that physicians preferentially prescribe SSRI antidepressants to patients at higher risk for suicide because these drugs are safer in overdose. However, this is unlikely to explain our findings for several reasons. Physicians frequently cannot identify patients at increased risk of suicide, particularly among the elderly (79, 80). Moreover, we selected comparison patients matched to cases on important characteristics (

Table 1 ), many of which are independently associated with suicide (54, 81, 82). In addition, we found consistent results regardless of a previous history of depression or psychiatric care, and in a separate nested case/control analysis restricted to patients receiving antidepressant therapy. Notably, no heightened risk of suicide was evident beyond the first month of treatment with SSRIs compared with other antidepressants. Had depression (rather than drug treatment) explained our findings, a more persistent risk should have been identified with SSRI therapy, since depressive symptoms rarely abate completely during the first month of therapy. Finally, the distinctly violent pattern of suicides during early SSRI therapy is consistent with previous reports and argues strongly against selection bias (15, 39), which would have yielded an increase in both violent and nonviolent suicide among patients treated with SSRI antidepressants.

Some limitations of our research merit emphasis. We used administrative data and had no direct measure of antidepressant doses or adherence, and the applicability of our findings to younger patients is not known. These limitations are particularly important given recent warnings regarding antidepressant use in adolescents

(21,

83) . We could not directly measure important risk factors such as bereavement and social isolation. Although administrative data are an imperfect means of identifying certain medical problems such as malignancy and alcoholism, differential detection of these conditions with SSRIs versus other antidepressant treatment is not likely to explain our findings. Although we used a population-based registry to identify suicides, some cases of nonviolent suicide in older patients may have been misattributed to natural causes

(84) . Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that SSRI antidepressants merely reduce the risk of suicide less effectively than other treatments.

Our study does not address the benefits of SSRI antidepressants and cannot establish the number of suicides prevented by treatment

(85 –

87) . The findings should not serve to anathematize SSRIs as a class, since they represent an important therapeutic option for patients with depression

(85) . Patients responding well to SSRI antidepressants should not discontinue therapy, and individuals with depression must not be deterred from seeking treatment based upon our findings

(55) . Indeed, in patients with major depression, the hazards of undertreatment almost certainly outweigh the risks of therapy, which our study suggests are low and transient. Further research is needed to explore the basis of our findings, including the possible role of genetic variability in drug response

(66,

68) . In the interim, our findings reaffirm the need for clinicians to reserve SSRI antidepressants for patients with established indications, monitor them closely after commencing treatment, and inform patients and their families of the possible emergence of suicidality during the first month of therapy.