All of the currently available information on the long-term course and outcome of borderline personality disorder comes from four large-scale, long-term, follow-back studies that were conducted in the 1980s

(1 –

4) . These studies found that the average patient with borderline personality disorder was functioning reasonably well a mean 14–16 years after his or her index admission. Each of these studies

(2,

4 –7) also tried to determine the best predictors of general outcome. A substantial number of factors were found to be associated with a good long-term outcome: high IQ

(4,

5), being unusually talented or physically attractive (if female)

(4), the absence of parental divorce and narcissistic entitlement

(7), and the presence of physically self-destructive acts during the index admission

(5) . A larger number of factors were found to be associated with a poor long-term outcome: affective instability

(5), chronic dysphoria (2), younger age at first treatment (2), length of prior hospitalization (5), antisocial behavior (4), substance abuse

(4), parental brutality

(4), a family history of psychiatric illness

(2), and a problematic relationship with one’s mother (but not one’s father)

(6) .

These studies were considered state of the art at the time they were conducted and added substantially to what is known about the long-term course of borderline personality disorder. However, they suffered from a number of methods limitations that are inherent in their follow-back design. Most relevant to the current study is the fact that many important predictor variables either were not assessed at all or were assessed only in the most rudimentary manner because they had to be rated from incomplete and unreliable chart material. In addition, only one of these studies assessed outcome at more than one point in time

(8), and none used an outcome that measured change from baseline.

The study is the first study to our knowledge to assess the relationship between a full array of clinically relevant predictor variables and time to remission from borderline personality disorder, which was assessed at five contiguous 2-year time periods. The group of patients with borderline personality disorder that we studied was large, carefully diagnosed, and socioeconomically diverse. In addition, symptomatic outcome was assessed blind to baseline predictor values, and a high level of retention had been maintained over the 10 years of prospective follow-up.

Method

The current study is part of a multifaceted longitudinal study of the course of borderline personality disorder: the McLean Study of Adult Development

(9) . All subjects were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. Each patient was first screened to determine that he or she 1) was between the ages of 18 and 35; 2) had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher; 3) had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and 4) was fluent in English.

After the study procedures had been explained, written informed consent was obtained. Each patient then met with a master’s-level interviewer who was blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses for a thorough psychosocial treatment history and diagnostic assessment. Four semistructured interviews were administered. These diagnostic interviews were 1) the Background Information Schedule

(10,

11), 2) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID)

(12),

3) the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R)

(13), and 4) the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders

(14) . The interrater and test-retest reliability of the Background Information Schedule

(10,

11) and the three diagnostic measures

(15,

16) have all been found to be good or excellent.

A childhood history of pathological and protective experiences, a family history of psychiatric disorder, and adult experiences of violence were assessed by a second rater who was blind to all previously collected information. Childhood experiences were assessed with the Revised Childhood Experiences Questionnaire

(17), a family history of psychiatric disorder was assessed with the Revised Family History Questionnaire

(18), and adult experiences of violence were assessed with the Abuse History Interview

(19) . The interrater reliability of these interviews has also been found to be good or excellent

(20 –

22) . Self-report measures with well-established psychometric properties assessing temperament and intelligence were also administered: the NEO Five-Factor Inventory

(23) and the Shipley Institute of Living Scale

(24) .

At each of five follow-up waves separated by 24 months, diagnostic status was reassessed with interview methods similar to the baseline procedures by staff members who were blind to baseline diagnoses. After informed consent had been obtained, our diagnostic battery was readministered (a change version of the SCID, the DIB-R, and the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders).

We defined time to remission as the follow-up period at which remission was first achieved. Thus, possible values for this time to remission measure were 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5, with time 1 for persons first achieving remission at the first follow-up period (at 24 months postbaseline), time 2 for persons first achieving remission at the second follow-up period (at 48 months postbaseline), time 3 for persons first achieving remission at the third follow-up period (at 72 months postbaseline), time 4 for persons first achieving remission at the fourth follow-up period (at 96 months postbaseline), and time 5 for persons first achieving remission at the fifth follow-up period (at 120 months postbaseline).

A discrete time-duration model was used to estimate the effects of explanatory factors on the probability of a patient with borderline personality disorder achieving remission. We used methods described by Prentice and Gloeckler

(25) in which it was assumed that the observations followed a continuous time-proportional hazards model, but because the data were grouped into 2-year intervals, a discrete hazards model was used to estimate the contribution of the independent variables to the hazard. Prentice and Gloeckler showed that a discrete hazards model generates unbiased estimates of the coefficients of a continuous time-proportional hazards model. In this discrete hazards model, the hazard of the patient achieving remission over the interval between follow-up waves t and t+1 is assumed to be constant over the interval between t and t+1, although the hazard may vary from one time interval to the next. In discrete time, the hazard is the conditional probability that the patient’s illness will remit on or before follow-up wave t, given that the patient has not achieved remission before wave t. Derived from the model are hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), adjusted for the effects of covariates included in the analytic models.

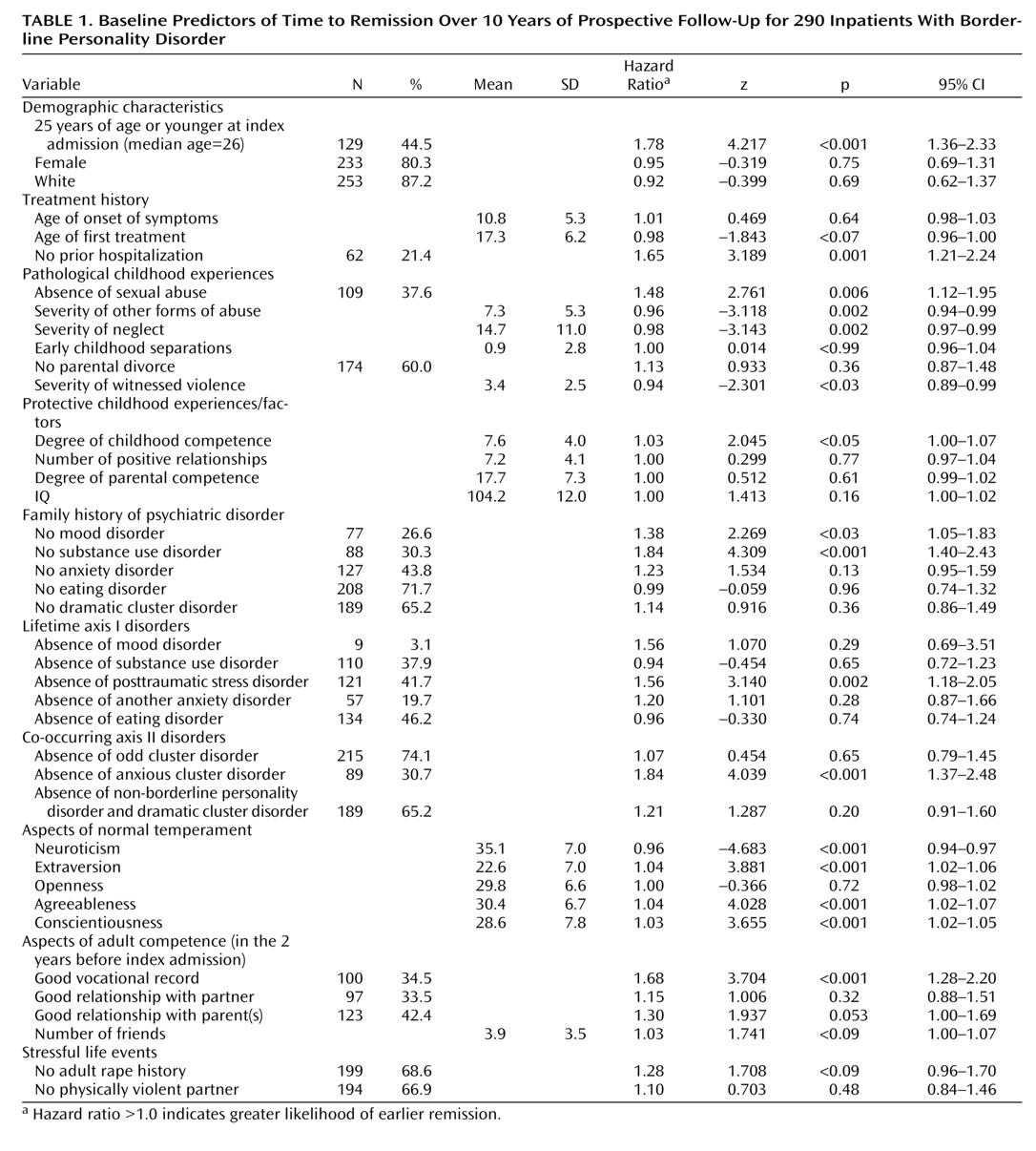

In carrying out the time-to-remission analyses summarized in this report, we first assessed the relationship between each baseline predictor variable and time to remission while controlling for the baseline severity of borderline psychopathology (as assessed by the total score on the DIB-R) and assessment period. These 40 variables are laid out in 10 groupings or “families” of predictors, and these families are similar to those used in recent studies of the course of dysthymic disorder

(26) and bipolar I disorder

(27) .

To select the predictor factors to be retained in the most parsimonious survival analysis model, we compared log likelihoods of a sequence of multivariable models. In these models, the baseline DIB-R score and assessment period were always included as covariates. This selection procedure started with the significant bivariate factors and stepped down to the most parsimonious model on the basis of significant change in the log likelihood. The significant within-family predictors were analyzed in roughly the chronological order of their impact. Demographic and treatment history variables were entered first because they are basic to the description of the group, followed by variables from each of the other predictive families (see

Table 1 for further details).

Categorical data are reported as numbers with percents; averaged continuous data are reported as means with standard deviations. Statistical significance required 2-tailed p<0.05.

Results

Two hundred and ninety patients met both DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder. In terms of baseline demographic data, 233 subjects (80.3%) were women, and 253 (87.2%) were white. The average age of the borderline subjects was 26.9 years (SD=5.8), their mean socioeconomic status was 3.4 (SD=1.5) (in which 1 was the highest and 5 was the lowest), and their mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score was 38.9 (SD=7.5), indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood.

In terms of continuing participation, 275 patients with borderline personality disorder were reinterviewed at 2 years, 269 at 4 years, 264 at 6 years, 255 at 8 years, and 249 at 10 years. All told, only 25 patients (8.6%) left the study before achieving remission from borderline personality disorder. We compared these 25 patients with borderline personality disorder to the other 265 on key demographic and clinical variables and found no significant between-group differences.

Over the 10 years of follow-up, 242 of 275 patients (88%) with at least one follow-up interview had a remission of his or her borderline personality disorder. (Remission was defined as no longer meeting either of our study criteria sets for borderline personality disorder: DIB-R or DSM-III-R.) In terms of time to remission, 95 of the 242 patients with borderline personality disorder (39.3%) who experienced a remission of their illness first experienced remission by their 2-year follow-up, 54 (22.3%) first remitted by the 4-year follow-up, 53 (21.9%) first remitted by their 6-year follow-up, 31 (12.8%) first remitted by the 8-year follow-up, and 9 (3.7%) by their 10-year follow-up.

Table 1 presents the baseline bivariate predictors of time to remission from borderline personality disorder. (Each row represents a separate discrete survival analysis that controlled for the effect of baseline severity of borderline psychopathology and time for that predictor.) As shown, 16 of these 40 variables were found to be significant in these discrete survival analyses. These 16 variables are younger age; no prior psychiatric hospitalization; no history of childhood sexual abuse; less severe childhood abuse of a verbal, emotional, or physical nature; less severe childhood neglect; less severe violence witnessed as a child; a higher degree of childhood competence; no family history of mood or substance use disorder; absence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxious cluster personality disorders; four facets of normal personality (low neuroticism and high extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness); and a good vocational record in the 2 years before the index admission.

As an example of how to interpret these findings, the adjusted hazard ratio for age dichotomized at the median of 26 is 1.53. This suggests a rate of time to remission differential of about 50% between younger (25 years of age and younger) and older (26 years of age and older) patients with borderline personality disorder, with younger patients more likely to achieve an earlier remission.

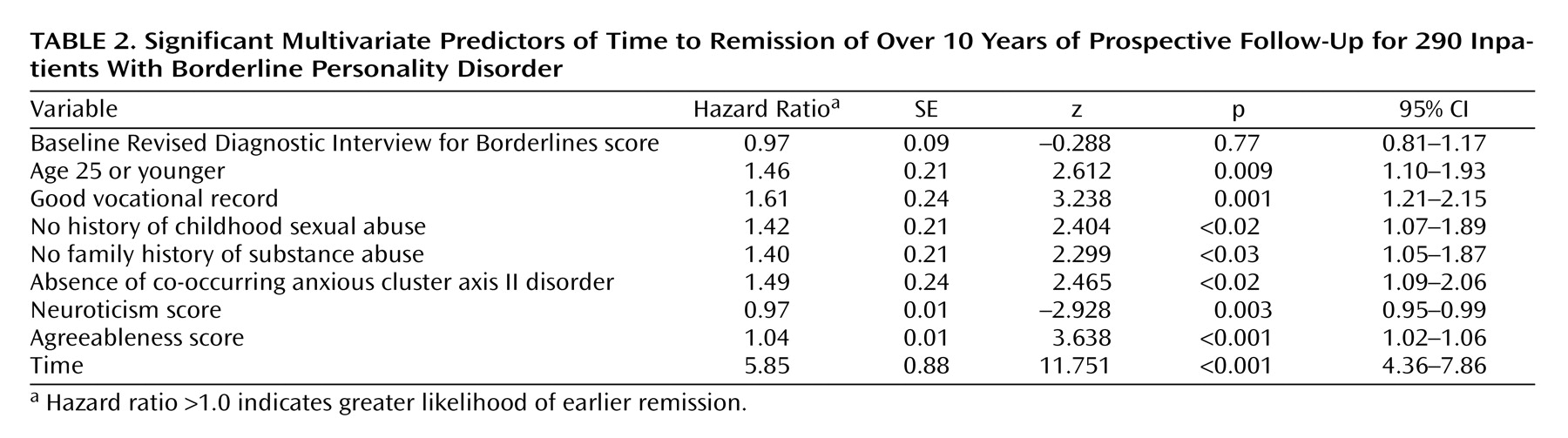

Table 2 shows the significant multivariate predictors of earlier time to remission of borderline personality disorder. As in the analyses summarized in

Table 1, both baseline DIB-R score and the assessment period were part of these discrete survival analyses, with control for baseline severity and time. As shown, the remaining seven predictors break down into two groups. The first—composed of younger age, good recent vocational record, no history of childhood sexual abuse, and no family history of substance abuse—consists of four key pieces of clinical information that are likely to be obtained during an initial evaluation. The second is composed of three predictors representing underlying aspects of temperament—absence of the anxious cluster personality traits commonly found in patients with borderline personality disorder

(28,

29), low neuroticism, and high agreeableness—two being elements of the five-factor model of normal personality believed to underlie borderline psychopathology

(30) . (We also calculated the percent of variance accounted for by this model by using McFadden’s pseudo-R-squared

[31] and found that it was 0.21.)

We repeated these analyses using the same variables but including indicators for each of the study’s follow-up periods. Using post hoc pairwise comparisons, we found that the hazard ratio associated with the period covering the time between baseline and the 2-year follow-up was significantly greater than the hazard ratio associated with each of the other time periods in the study (2-year follow-up versus 4-year follow-up: χ 2 =22.9, df=1, p<0.0001; 2-year follow-up versus 6-year follow-up: χ 2 =13.4, df=1, p=0.0002; 2-year follow-up versus 8-year follow-up: χ 2 =15.2, df=1, p=0.0001; 2-year follow-up versus 10-year follow-up: χ 2 =40.2, df=1, p<0.0001).

Discussion

All families of predictors were represented in the significant bivariate predictors of time to remission from borderline personality disorder, except for stressful life events or experiences of violence as an adult. Thus, factors pertaining to demographic characteristics, treatment history, adverse childhood experiences, protective childhood experiences, family history of psychiatric disorder, co-occurring axis I disorders, axis II co-occurrence, facets of normal personality, and psychosocial functioning in the 2 years before the index admission were all found to have a significant relationship to time to remission. More specifically, 16 of the predictor variables that were studied were found to significantly predict earlier time to remission after we controlled for baseline severity and the passage of time. One of these predictors is demographic in nature (younger age), whereas another pertains to treatment history (no prior psychiatric hospitalizations). Four are from the adverse childhood experiences family of predictors (no history of childhood sexual abuse; less severe childhood abuse of a verbal, emotional, or physical nature; less severe childhood neglect; and less severe violence witnessed as a child), one pertains to childhood protective factors (higher degree of childhood competence), and two pertain to family history of psychiatric disorder (no family history of mood or substance use disorder). Two are co-occurring disorders (absence of PTSD and absence of anxious cluster personality disorders), and four are aspects of normal personality (low neuroticism, high extroversion, high agreeableness, and high conscientiousness). Finally, one is an element of recent psychosocial functioning (a good vocational record).

The variables that were not found to be significant in these bivariate analyses are also interesting because of their presumed clinical importance (e.g., gender, early childhood separations) and the fact that some of them (e.g., younger age at first treatment, absence of parental divorce, high IQ) have been found to be significant predictors of outcome in other long-term studies of the course of borderline personality disorder

(2,

4,

5,

7) .

In terms of significant multivariate predictors, seven of the bivariate predictors remained significant after we controlled for baseline severity and time: younger age, absence of childhood sexual abuse, no family history of substance use disorder, good vocational record, absence of an anxious cluster personality disorder, low neuroticism, and high agreeableness. In terms of specific variables, the association of younger age with earlier time to remission runs counter to the clinical lore of borderline personality disorder (and other psychiatric disorders), where getting older is believed to lead to a lessening of symptomatic impairment. However, it makes clinical sense that younger people do better symptomatically because they may not yet be hampered by life mistakes and are probably less likely to be chronic patients.

No personal history of being sexually abused as a child and a family history of substance abuse also make clinical sense as predictors of a good symptomatic outcome because they suggest a childhood less marred by trauma and turmoil. In addition, a stable work or school history was a strong multivariate predictor of time to remission. This suggests that adult competence in the psychosocial realm is important for symptomatic improvement. This may be because these patients struggle harder to get better or, at least, may be less attached to the patient role. It may also be that they are more innately competent than borderline patients who perform more poorly.

The triad of temperamental predictors suggest that a higher level of agreeableness is helpful in getting better symptomatically, whereas a higher level of neuroticism and avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, and self-defeating personality traits make it harder to get well. This, too, makes clinical sense. Neuroticism, while an aspect of normal personality, is also a compilation of symptomatic states, such as anger, anxiety, and depression. Clearly, the patients with borderline personality disorder who are burdened with a higher degree of these states or traits would have a harder time making symptomatic progress. In a similar manner, borderline patients burdened by being shy, dependent, unduly perfectionist, and masochistic might have a harder time making the effort to get well. However, the borderline patients endowed with a more affiliative or agreeable personality (e.g., not being particularly argumentative or manipulative) may have an easier time getting other people to support and assist them emotionally. This, in turn, could be crucial to the process of getting better symptomatically because it could ameliorate the abandonment concerns that tend to intensify for borderline patients as progress is being made.

It should also be noted that the severity of borderline psychopathology was not a significant predictor of time to remission in this multivariate analysis. This may be because of the fact that all of the patients in this study were severely ill inpatients. Time, however, was a strong predictor of time to remission. This may suggest that the passage of time itself is important in the course of borderline psychopathology. It may also suggest that some type of maturation process is occurring over time. The 2-year period after index admission, in particular, seemed to be a time of change and progress. More specifically, almost 40% of the patients with borderline personality disorder who eventually remitted experienced their first remission in the first 2 years of follow-up.

It is also important to note that the “winnowing” procedure that was used to identify variables within each analytic family may have introduced some optimistic bias in the hazard ratio estimates (and their 95% CIs) found in our multivariate model. Because of the substantial strength of the significant results that we report, we believe that this potential bias is unlikely to have materially affected the direction and scope of these results.

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that prediction of symptomatic outcome for borderline personality disorder is multifactorial in nature. It encompasses predictors that are routinely assessed in clinical practice because of their clinical importance, such as childhood history of sexual abuse and family history of substance use disorders. It also encompasses predictors that are commonly discussed in treatment but may not receive the attention that they deserve, such as stage of adult development and adult competence. Finally, prediction of time to remission seems to encompass aspects of temperament, such as low levels of shyness and undue dependency, which are probably noticed but rarely discussed in clinical practice.