Aripiprazole is an atypical antipsychotic agent with a novel mechanism of action that has been successfully employed in medication therapy for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders

(1,

2) . It also has Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of the manic and mixed states of bipolar disorder. A partial agonist at dopamine D

2 and serotonin 5-HT

1A receptors and an antagonist at 5-HT

2A receptors, it is thought to have a stabilizing effect on the dopamine-serotonin system that is advantageous because it is associated with fewer adverse effects

(3 –

9), although some of them are reported to be severe

(10,

11) .

The characteristics that make aripiprazole interesting in the treatment of schizophrenia

(12) and bipolar mania

(13) could also prove to have a positive influence on the treatment of other psychiatric illnesses

(14 –

16) . One illness that is difficult to treat is borderline personality disorder

(17 –

22), which is characterized by a pervasive pattern of severe psychopathological symptoms with instability of affect regulation, impulse control, and aggression

(23 –

29) . Dysfunctions in the serotoninergic and dopaminergic systems have been demonstrated in—and considered as possible causes for—symptoms associated with the disorder

(30 –

33) . Several studies on the use of traditional

(34) and atypical antipsychotic agents in patients with borderline personality disorder

(35 –

36) have shown a positive effect on individual symptoms

(34,

37 –41) . However, we are not aware of any study evaluating aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. In the present double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the influence of aripiprazole on the multifaceted psychopathological symptoms and aggression of patients with borderline personality disorder was investigated.

Method

Subjects

Fifty-seven subjects ages 16 and older who were disturbed by moodiness, distrustfulness, impulsivity, and painful, difficult relationships were recruited through advertisements. They were screened on the telephone to assess whether they met DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder. A general medical history was also taken.

The subjects participated in face-to-face interviews. Possible side effects were fully explained, and written informed consent was obtained. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID II) were then carried out. Subjects were included if they met criteria for borderline personality disorder. They then underwent physical and laboratory examinations.

Criteria for exclusion (N=5) were schizophrenia, current use of aripiprazole or another psychotropic medication, current psychotherapy, pregnancy (including planned pregnancy or sexual activity without contraception), current suicidal ideation, or current severe somatic illness.

Assessment

The symptom checklist (SCL-90-R) is a self-report inventory that measures physical and mental symptoms during the previous week on nine scales: somatization, obsessive-compulsiveness, insecurity in social contacts, depression, anxiety, aggressive/hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid thinking, and psychoticism. The Global Severity Index (GSI) measures the person’s basic mental stress on a 5-step Likert scale. Transformation of the raw values to T values, which take sociodemographic factors into consideration, permits classification of individual cases. T values of 60 or more are regarded as mildly increased, of 70 or more as greatly increased, and of 75 or more as very greatly increased. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) ranges from r=0.75 to r=0.87

(42) .

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)

(43) is a validated scale that quantifies the severity of depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.52 and 0.95; retest correlation between 0.65 and 0.81), including depressed mood, vegetative, and cognitive symptoms of depression and comorbid anxiety symptoms, and rates them on either a 5-point (0–4) or a 3-point (0–2) Likert scale. It provides ratings on current DSM-IV symptoms of depression, with the exception of hypersomnia, increased appetite, and concentration/indecision.

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A)

(44) is a validated scale that quantifies the severity of anxiety, regardless of the etiology (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.74 and 0.96; retest correlation between 0.64 and 0.96) on a 5-point (0–4) Likert scale covering 14 psychological and physical symptoms.

The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory measures anger and the expression of anger (women: Cronbach’s alpha=0.75; retest correlation after 8 weeks=0.70–0.76) on five scales—state anger: a subjective state of anger at the time of measurement; trait anger: a readiness to react with anger; anger in: a tendency to repress anger; anger out: a tendency to express anger; and anger control

(21,

22,

45) .

The necessary group size was calculated for a type I error rate of 5% (z

1 =1.96) and a power analysis of 80% (z

2 =0.84) based on the means (m

1 =57.2 and m

2 =67.8) and SDs (s

1 =14.3 and s

2 =12.9) for the psychoticism scale of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey, which were obtained from a small pilot study. The formula is the number per group as follows: [(z

1 +z

2 )

2 × (s

1 2 +s

2 2 )]/(m

1 –m

2 )

(46) . Based on this analysis, 52 patients were required for an aripiprazole trial

(46) . The random assignment was carried out confidentially by the clinic administration and arranged so that the same number of patients would be treated with the active drug (N=26, 21 women and 5 men) as with a placebo (N=26, 22 women and 4 men).

Between June 2004 and April 2005, the subjects received medication in a blinded manner, which constituted either 15 mg/day of aripiprazole or a matching placebo

(47,

48) . The dosage remained constant. Tablets were supplied in numbered boxes. Both the subjects and the clinicians were blinded regarding the assignment of aripiprazole or placebo. The subjects were tested with the SCL-90-R, the HAM-D, the HAM-A, and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory every week. During the course of the trial, the intermediate results were not analyzed. After 8 weeks, both groups were tested for the last time and physically examined. Five subjects who missed more than two weekly evaluations dropped out. The questionnaires were filled out by the patients both independently and anonymously.

Data Analysis

We used the statistical program SPSS, Version 11 (SPSS, Chicago). Because the data were not normally distributed, the Mann-Whitney U test was performed for comparison of continuous variables. We employed means, SDs, changes between two groups with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and probability (p) for reporting the treatment results according to the intent-to-treat principle

(46) .

Ethical Considerations

The study was planned and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical laws pertaining to the medical profession, and its design was approved by the clinic’s ethics committee. The study was conducted independent of any institutional influence and was not funded.

Results

The patients in the aripiprazole group were a mean age of 22.1 years (SD=3.4) (placebo group: mean=21.2 years, SD=4.6); 11 (42.3%) were in a relationship with a significant other (placebo group: N=9, 34.6%); seven were laborers (26.9%) (placebo group: N=8, 30.8%); 14 were office workers (53.8%) (placebo group: N=15, 57.7%); and five were homemakers (19.2%) (placebo group: N=3, 11.5%).

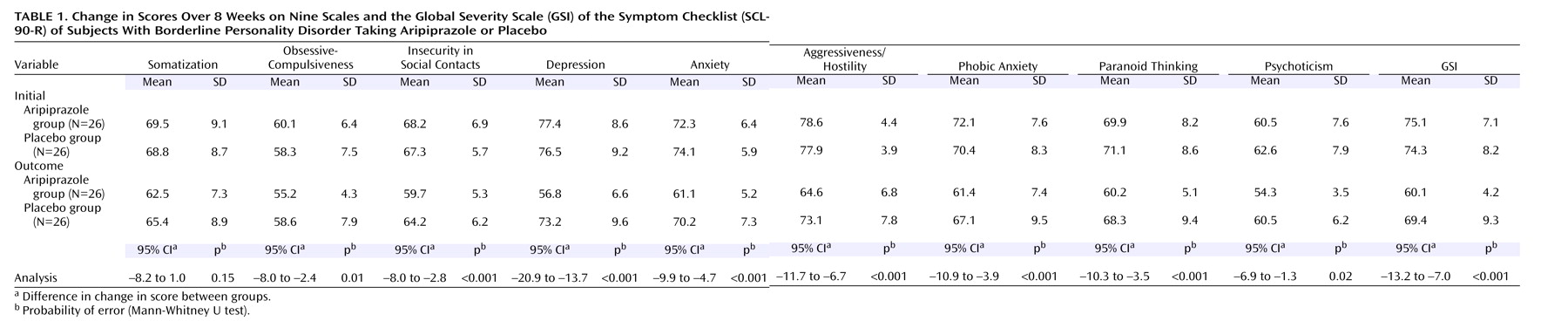

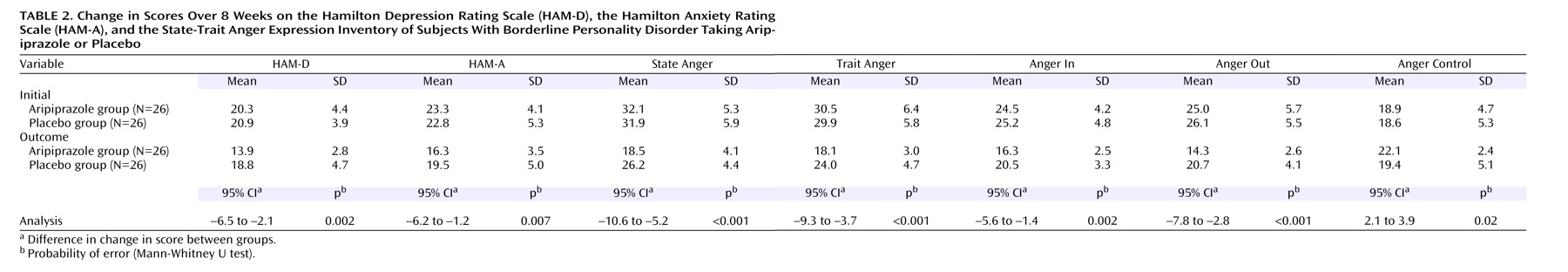

Eighteen had had previous psychotherapy (69.2%) (placebo group: N=19, 73.1%); all had received psychotropic drugs, and 10 had been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons (38.5%) (placebo group: N=11, 42.3%). Their psychiatric comorbidity included depressive disorders (aripiprazole group: N=21, 80.8%; placebo group: N=22, 84.6%), anxiety disorders (aripiprazole group: N=16, 61.5%; placebo group: N=14, 53.8%), obsessive-compulsive disorders (aripiprazole group: N=3, 11.5%; placebo group: N=3, 11.5%), and somatoform disorders (N=18, 69.2%; placebo group: N=19, 73.1%). The patients’ initial measurements with the SCL-90-R (

Table 1 ) and the HAM-D, the HAM-A, and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (

Table 2 ) at the time of random assignment revealed no essential differences between the two groups. At the beginning of the study, both groups had distinctly modified SCL-90-R (

Table 1 ), HAM-D, HAM-A, and State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory scores (

Table 2 ), indicating the presence of multiple psychopathological symptoms.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the rates of change between the aripiprazole and the placebo groups over the course of the entire study. The aripiprazole group experienced a significantly greater rate of change than the placebo group on most of the SCL-90-R scales (with the exception of somatization), as well as on the HAM-D and the HAM-A and all of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory scales.

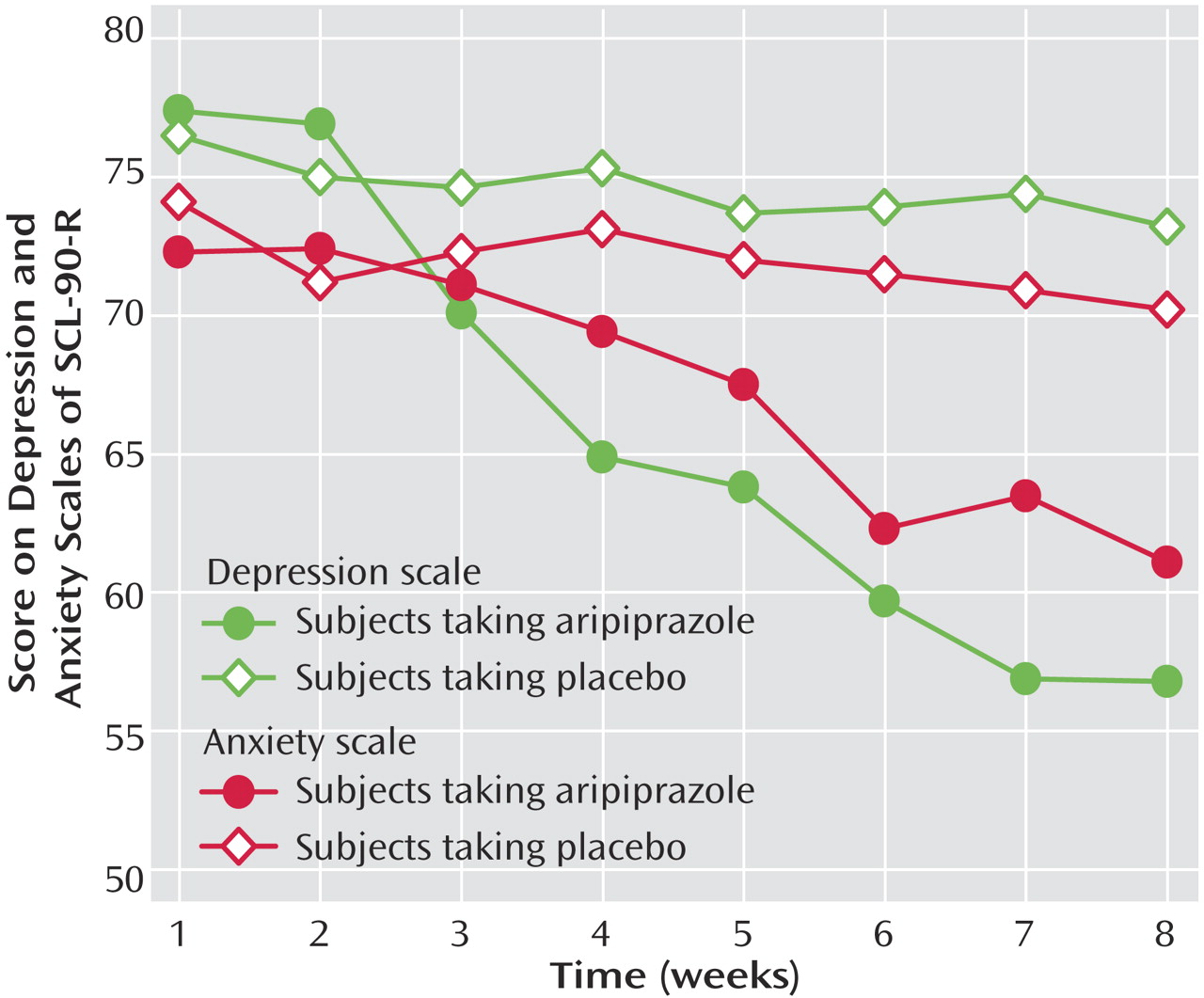

Figure 1 shows the changes over time on the depression and anxiety scales of the SCL-90-R for both groups. On the anxiety scale, aripiprazole was initially associated with a gradual change but on the depression scale, with a rapid change. Self-injury was observed in both groups (8 weeks before therapy—aripiprazole group: seven of 26, placebo group: five of 26; over the 8 weeks of therapy—aripiprazole group: two of 26, placebo group: seven of 26). Neither serious side effects nor suicidal acts were observed during the study. No significant weight changes were observed.

Discussion

Both groups were comparable in light of their sociodemographic and medical data, comorbidity

(29,

49), and initial measurements with the SCL-90-R, the HAM-D, the HAM-A, and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory.

Aripiprazole treatment resulted in a significantly greater rate of improvement than did placebo on all of the SCL-90-R scales, especially the obsessive-compulsive, insecurity in social contacts, depression, anxiety

(49,

50), aggressiveness/hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid thinking, and psychoticism scales

(42) . These findings conform to previous reports

(3 –

6,

8,

12,

13,

16) but clearly broaden the range of possible psychological symptoms that can be positively influenced through aripiprazole. In all, aripiprazole resulted in a significant reduction of global psychological stress (as measured by the GSI [

Table 1 ]).

On the HAM-D and the HAM-A scales, the aripiprazole group experienced greater change than the placebo group. The difference in change between both groups was significant, which supports previous findings of antidepressant and anxiolytic effects from aripiprazole

(8) .

Aripiprazole treatment resulted in a significantly greater rate of change than did placebo on four State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory scales. Thus, aripiprazole was more effective in treating the aggression component of borderline psychopathology. Among our patients, aripiprazole appeared to influence the intensity of the subjective state of anger (state anger) as well as their readiness to react with anger (trait anger). Furthermore, the tendency to direct anger outward (anger out) and inward (anger in) decreased significantly. This is important because the socially desirable tendency to control anger was strengthened (anger control).

The most common side effects of aripiprazole are headache, insomnia, nausea, numbness, constipation, and anxiety

(1,

2,

13) . No significant weight change was observed

(1,

2) . This supported findings from Keck et al.

(13) that aripiprazole is a safe and well-tolerated agent.

Aripiprazole appears to be a safe and effective agent for improving not only the symptoms of borderline personality disorder but also the associated health-related quality of life and interpersonal problems.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Despite a valid power analysis, the group was small. The length of this trial was only 8 weeks, which possibly reduced the failure rate. The study focused on only three dimensions of borderline personality disorder, namely, affective dysregulation, aggressive impulsivity, and cognitive perceptual impairment. The effects of aripiprazole on the fourth dimension—disturbed relationships—were not evaluated. Finally, the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder

(50), a new clinician-rated outcome measure specifically designed for borderline personality disorder, was not available in the German language when we began the study. Additional research is needed to see if these results can be replicated and how long-lasting the benefits are.