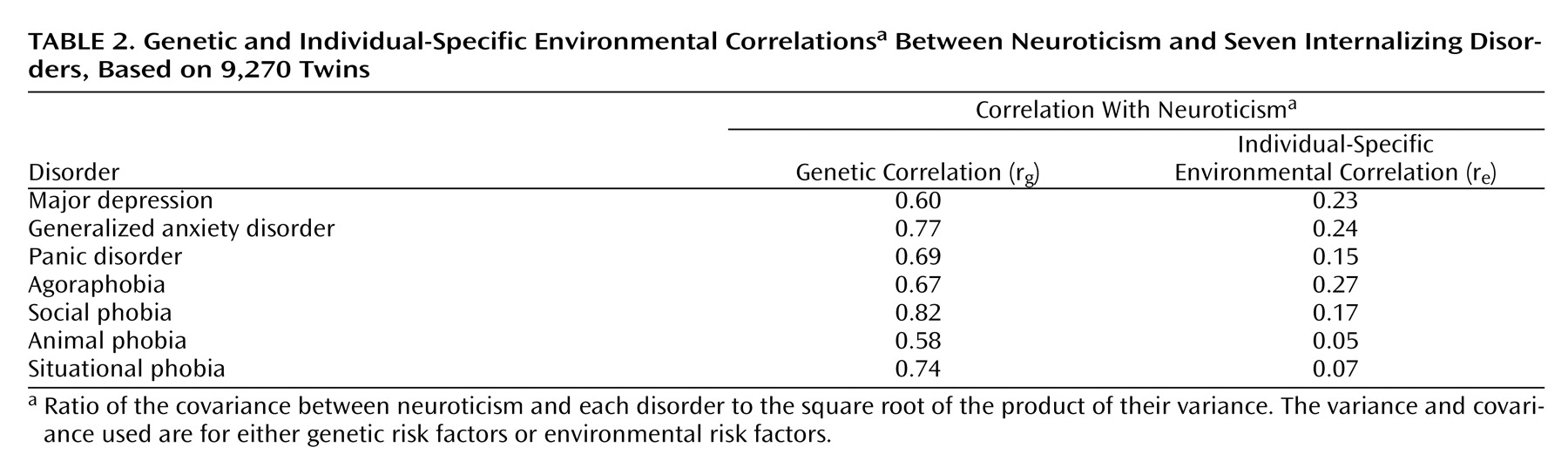

In this study we used multivariate modeling of twin data to examine the genetic and environmental risk factors shared by the personality trait neuroticism and a range of internalizing disorders. Our results suggest that the genetic factors underlying neuroticism are largely shared with those that influence liability to these conditions. Environmental risk factors, on the other hand, are only modestly correlated between these phenotypes. Furthermore, shared genetic factors account for a substantial amount of the comorbidity among the internalizing disorders, especially the genetic factors shared with neuroticism. These effects are roughly the same in men and women.

Relation to Previous Findings

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the factors underlying the relationship between neuroticism and a range of internalizing

disorders. A large, population-based study of Australian twins that examined the covariation between neuroticism and current depression and anxiety

symptoms showed genetic correlations between symptom scores and neuroticism of about 0.8 in both sexes

(5) . Our group previously published the results of separate bivariate analyses on the sources of covariation between neuroticism and major depression

(6) and between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder

(7), with findings consistent with those in the current study.

Several large, population-based phenotypic factor analytic studies examining comorbidity among psychiatric disorders have provided evidence for a single, higher-order “internalizing” factor that accounts for correlations among anxiety and depressive disorders and differentiates itself from an “externalizing” factor, which relates to the substance use and antisocial personality disorders

(17,

18) . The internalizing factor is made up of two lower, correlated factors, the first roughly corresponding to an “anxiety-misery” factor, which loads most strongly on major depression, dysthymia, and generalized anxiety disorder, and the second a “fear” factor, which loads primarily on panic and phobic disorders. This model has been expanded by our group through a population-based twin sample version of a similar factor analysis that allows differentiation of genetic and environmental components of these factors

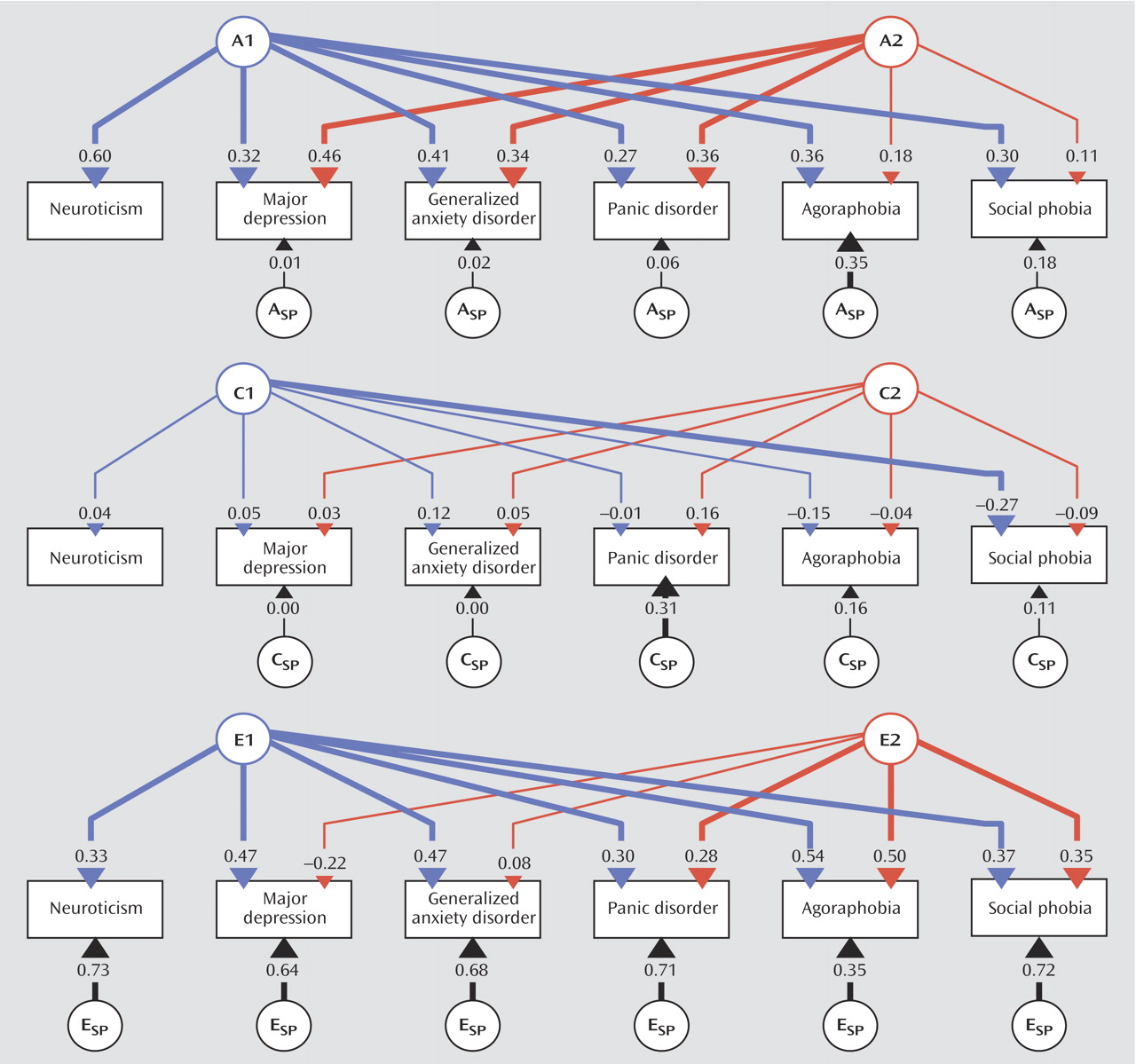

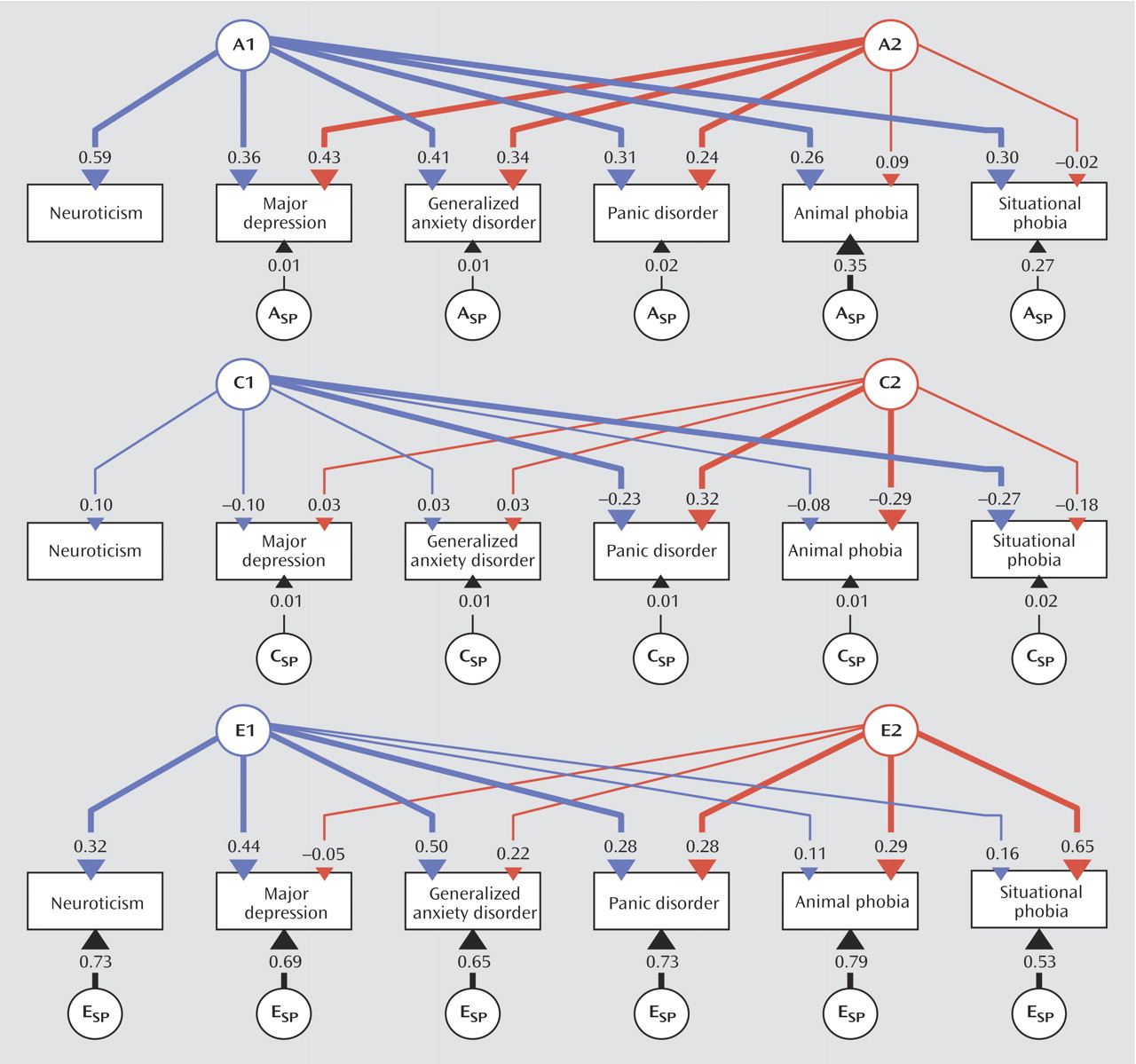

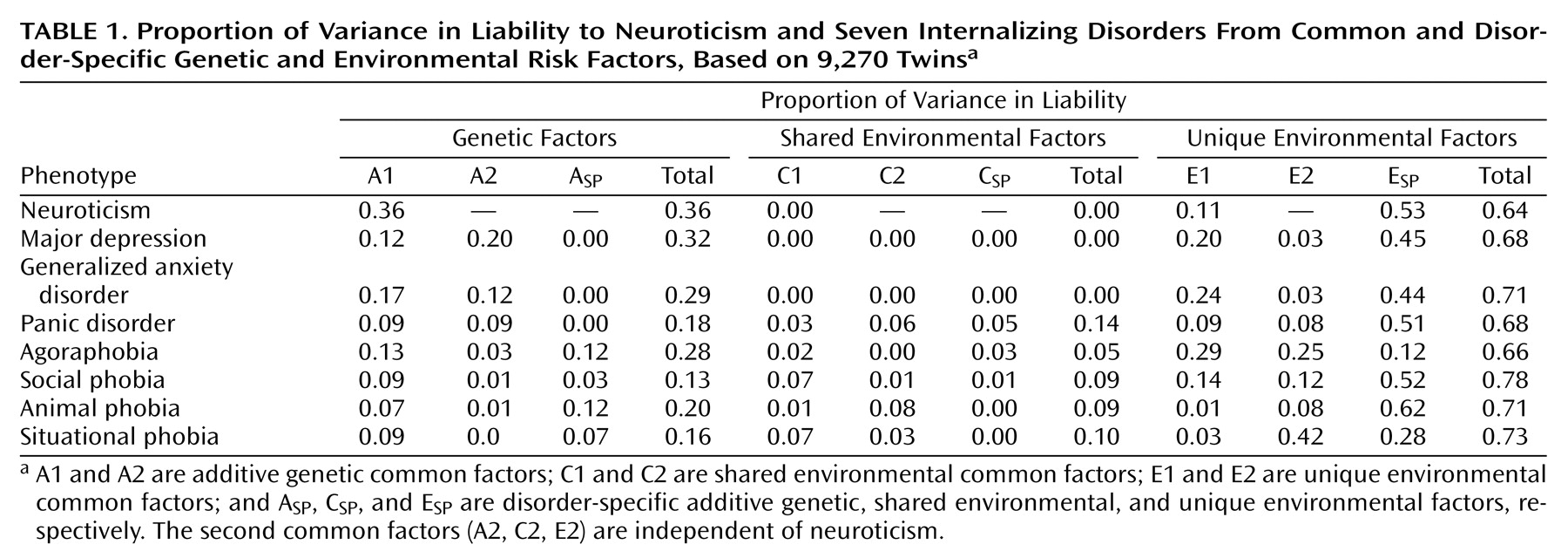

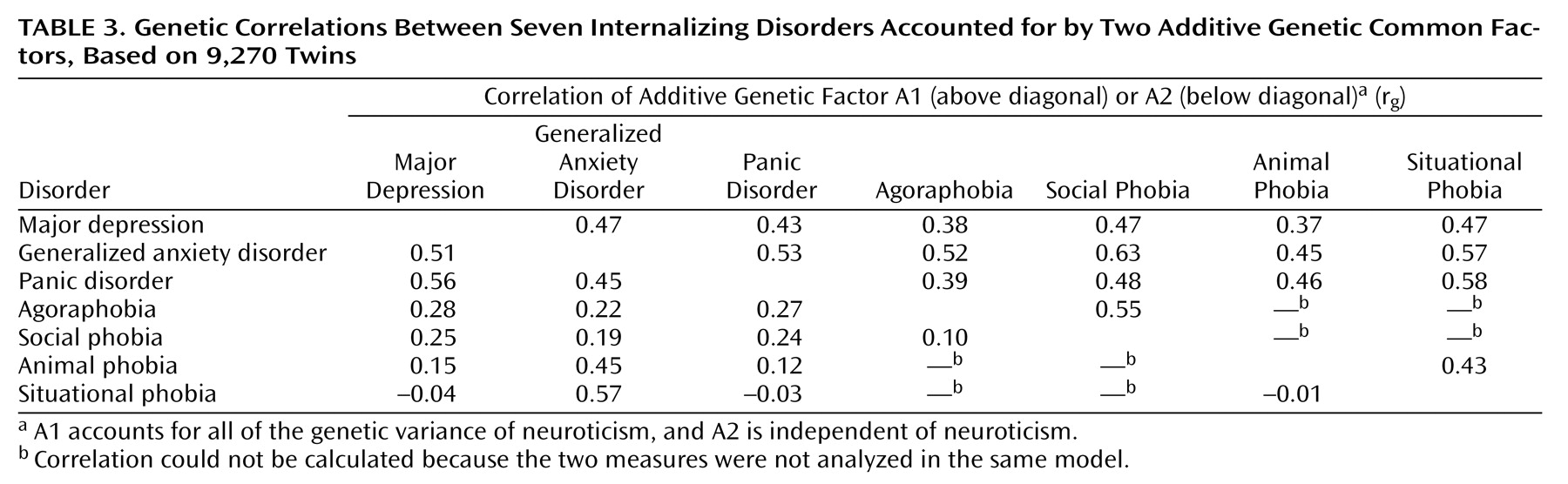

(19) . That study identified internalizing and externalizing genetic risk factors that help explain the phenotypic factor structure, the former being made up of analogous lower-order “anxiety-misery” and “fear” factors. In this context, the current analysis ascribes a somewhat different partitioning of this two-factor internalizing structure into genetic factors specifically shared or not shared with the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire concept of neuroticism. The genetic factors underlying individual differences in neuroticism exhibit significant overlap with the genetic risk for major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and the phobias. They also account for a sizable proportion of the observed comorbidity among these disorders. Other common genetic risk factors not shared with neuroticism are important for major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder but hardly at all for phobias. In addition, each phobia type has contributions from disorder-specific genetic factors not accounted for by the two common genetic factors. One might speculate that, had we been able to analyze models with more than two common factors, a third factor might have been identified that represents genetic risk shared among the phobias alone.

Gene Studies

These findings have several important implications for identifying candidate susceptibility genes for depressive and anxiety disorders. First, although many published studies have used the assumption that the

phenotypic relationship between neuroticism and these conditions justifies its use in searching for genes for anxiety or depressive disorders, this study informs and extends those findings by establishing neuroticism as a reasonable target endophenotype in molecular genetic studies of a range of internalizing disorders. This has increasing relevance as both association studies

(25) and linkage studies

(26) have identified putative genetic regions that influence individual variation in neuroticism. Second, unlike in classic, Mendelian disorders, where pure, homogeneous phenotypes are the most powerful for identifying disease genes, for complex conditions like those studied herein, a phenotype that combines information from personality constructs, such as neuroticism, and several disorders may provide a more efficient initial target for gene-finding studies

(27,

28) . However, these results also show that neuroticism does not capture all the genetic variance underlying the internalizing disorders. Indeed, a second, neuroticism-independent common genetic factor was identified that accounted for a proportion of the genetic variance for the nonphobic internalizing disorders (major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder) that was similar to the proportion accounted for by the neuroticism-related common genetic factor.

Limitations

The results of this analysis should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, we used broadened diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder to increase prevalence and maximize our power to estimate model parameters. Prior analyses suggest that these approaches reflect the same continuum of liability as the fully syndromal disorders

(11,

12) . Consistent with this, our prior bivariate analysis of neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder produced findings that did not strongly depend on the stringency of the definition used

(7) .

Second, although the overall risk structure was generally invariant to sex, our study did not possess sufficient statistical power to determine whether the magnitudes and sources of genetic correlations among the phenotypes were the same or different in men and women. Thus, while such differences would have important implications for identifying susceptibility genes for these conditions, we were limited, despite the size of our sample, in our ability to establish their presence with a high degree of confidence.

Third, we had to restrict our analyses to the simultaneous modeling of six phenotypes in order to keep computer run times tractable; therefore, the analysis for animal and situational phobias was separate from that for agoraphobia and social phobia. This produced estimates of path coefficients and correlations for the remaining phenotypes (neuroticism, major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder) that differed somewhat from one model to another owing to stochastic variation. Calculating confidence intervals would have been desirable to estimate their precision, but the computer run times would have been prohibitively long.

Fourth, the findings of this analysis are predicated on the assumptions of the method used, that is, structural equation modeling of twins. These assumptions include independence and additivity of the latent variables, absence of assortative mating, and equal correlation in monozygotic and dizygotic twins for environmental experiences of relevance to the trait under study

(15) . If the latter, known as the equal environment assumption, is violated, the greater similarity for monozygotic twins could potentially result from their increased environmental similarity instead of greater genetic similarity, potentially biasing the correlations obtained. Using several approaches to this problem, we have not been able to detect such violations for the psychiatric disorders examined in this study

(29,

30) .

Fifth, neuroticism and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses were each assessed at one time point, which potentially confounds the effects of individual-specific environment and measurement error, reducing the corresponding estimates of genetic effects. For example, we found, for major depression in our sample of female-female twin pairs, that improving the diagnostic reliability by reducing error through multiple, sequential assessments increased the heritability estimate substantially

(31) . This measurement “noise” would reduce the correlations between twins and between measures. Given the low reliability for some measures, such as generalized anxiety disorder, this may have a substantial effect on our results. If this is the case, our analysis may have underestimated both genetic and environmental correlations.

Sixth, we were unable to examine the longitudinal relationship between neuroticism and the risk of developing any of the psychiatric disorders with the current design. In particular, we cannot differentiate state (i.e., “in episode”) and scar (“postepisode”) effects of illness on neuroticism that may disturb it from its premorbid or baseline level

(32) . Similarly, while it is possible that some depressive and anxiety disorders might directly increase the risk for other disorders that we studied, our design does not test this model of causation.

Seventh, because the sample was made up entirely of Caucasian twin subjects born in Virginia, these results may not generalize to other groups.