Assessment of Psychiatric Disorders

At ages 18 and 26 years, the study members were administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule

(25,

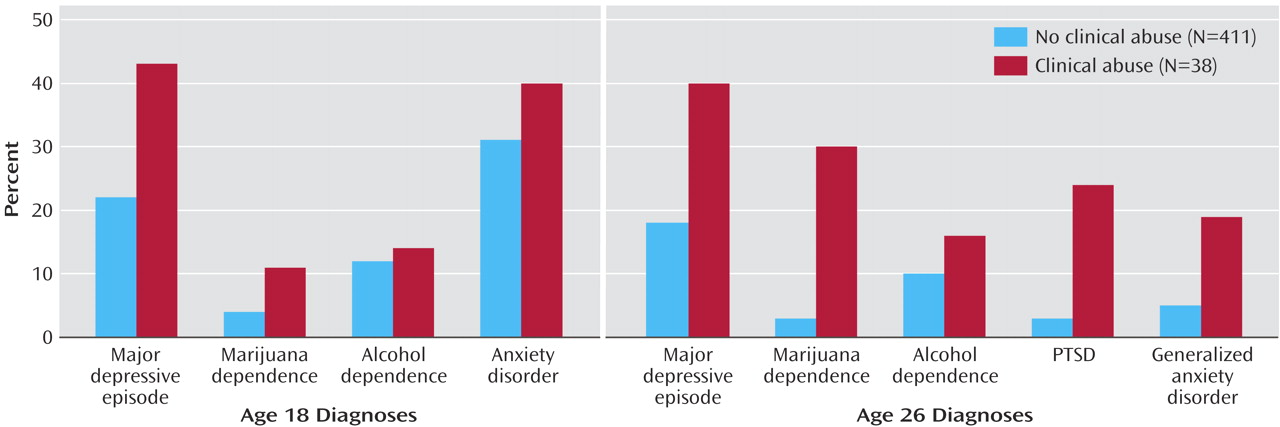

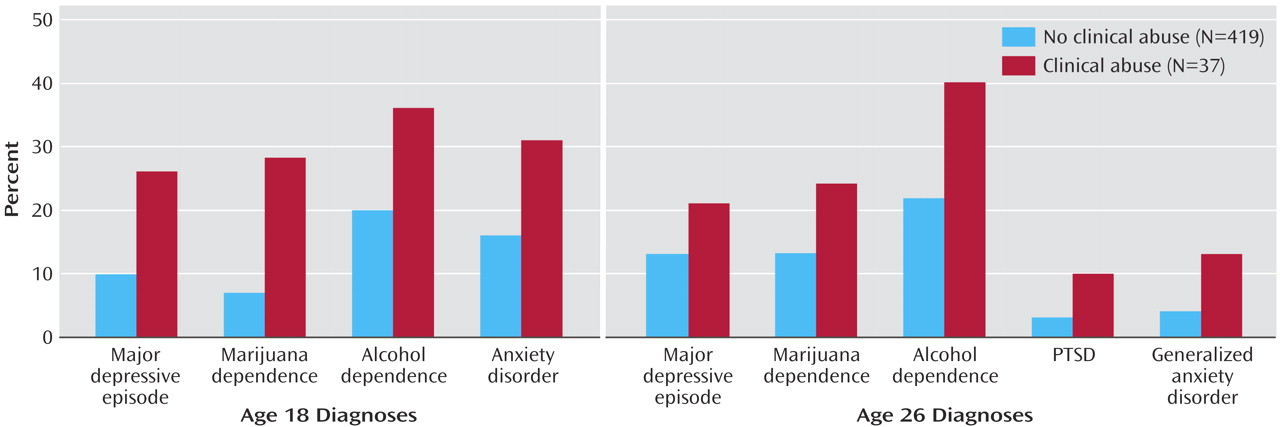

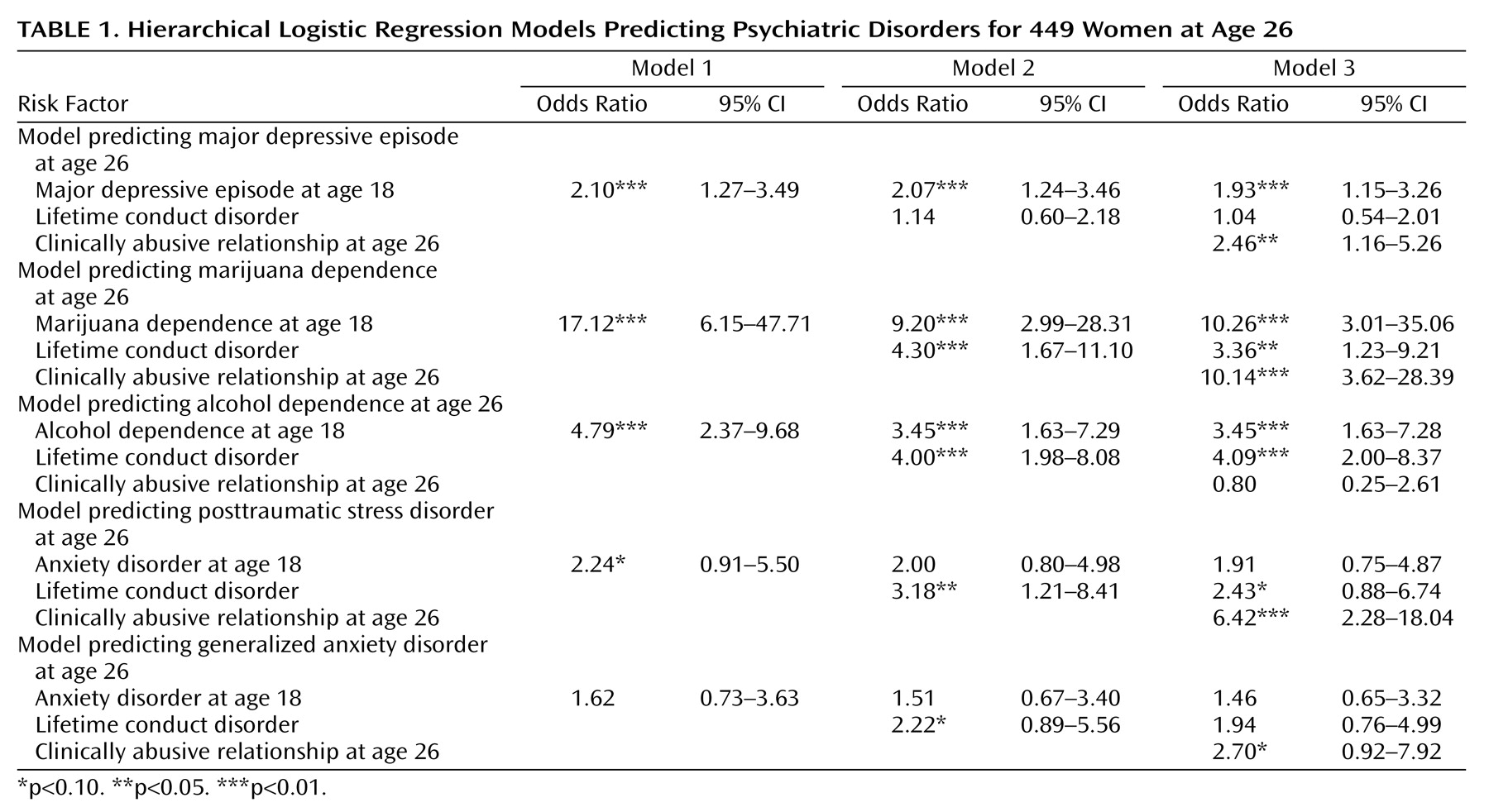

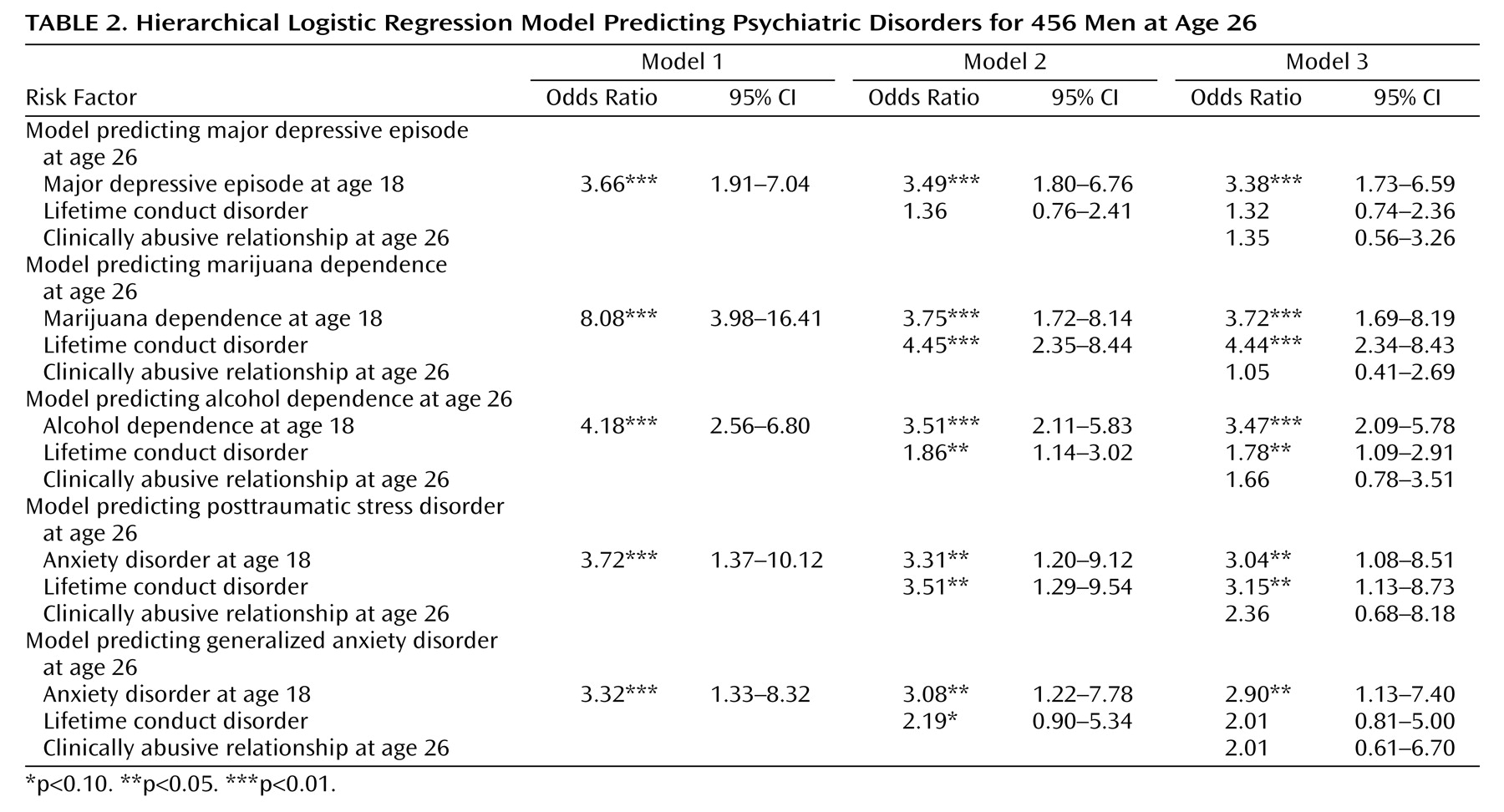

26) . Psychiatric disorders were diagnosed according to DSM-III-R at age 18 and DSM-IV at age 26, with a reporting period of the past 12 months. For the present study, we analyzed diagnoses at both assessment points for major depressive episodes, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and generalized anxiety disorder were assessed at age 26; their antecedent at age 18 was a measure of any anxiety disorder (including panic disorder, social phobia, simple phobia, generalized anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder). Finally, we included a lifetime diagnosis of DSM-IV conduct disorder, assessed at ages 11, 13, 15, and 18

(24) .

We selected age 18 as the assessment point for prior psychopathology because it was the most recent assessment point that antedated all relationships about which we had partner abuse data. The majority of the participants still lived at home during the reporting year before their 18th birthday, and few had yet cohabited with a partner. None of the relationships on which the study members reported partner abuse at ages 24–26 were ongoing at the age 18 assessment.

Assessment of Partner Abuse

The Partner Conflict Calendar was used to identify individuals in abusive relationships that entailed clinically significant consequences, such as injury, medical treatment, or agency involvement

(6) . The Partner Conflict Calendar covered relationships in the 3 years before the interview. The relationships had been ongoing an average of 3.3 years (SD=2.7) before the interview. Before beginning the Partner Conflict Calendar, study members first completed a Life History Calendar, a visual data collection grid for obtaining reliable retrospective reports about demographic changes and other life events. The Partner Conflict Calendar was laid beside the completed Life History Calendar to cue memories about any months in which partner abuse occurred during the past 3 years. This calendar method capitalizes on advances in survey methods and cognitive psychology to collect reliable retrospective data. It is a visual aid and reminds subjects about streams of events rather than isolated events. It contextualizes questions about life events by linking them to other events. We and others have found excellent reliability for the Life History Calendar method, above 90% agreement over test-retest periods up to 5 years

(27,

28) .

A violent incident on the Partner Conflict Calendar was defined by showing the respondent a card with “pushing, shoving, twisting arm, grabbing, shaking, throwing, choking, strangling, using a knife or a gun, kicking, biting, punching, and slapping” in large block letters. The respondents were asked to recall months in which any of these things had happened “between you and your partner.” The interviewers then asked follow-up questions about each month to ascertain the frequency of incidents, whether either partner was injured in that month, whether treatment was sought, and whether agencies became involved (police, shelter or refuge, counselor or therapist, lawyers or courts).

The test-retest reliability of the Partner Conflict Calendar reports were evaluated by administering it on two occasions, 1 month apart, to 24 women inmates in the Wisconsin women’s community corrections system

(6) . Those women reported abuse in an average of 8 months of their 36-month calendars, totaling an average of 60 violent incidents per woman. Although the women inmates had extensive substance abuse histories, low cognitive ability, and complex histories of domestic violence, their 1-month test-retest agreement was very good when it was aided by the calendar method, yielding kappas from 0.6 to 1.0 for the precise timing of months with violence. The test-retest correlations were above 0.80 for the number of months with violence, injury, medical treatment, and agency involvement.

We did not attempt in the context of the Partner Conflict Calendar to ascertain which partner had been the perpetrator or victim because prior research documents that more incidents involve mutual violence than one-sided violence. Moreover, our pilot research revealed that retrospective recall of which partner hit first is unreliable. In our earlier work with this group, the most seriously or “clinically abusive” group had the highest level of mutuality on standardized self-report measures of abuse, and both partners’ characteristics predicted reciprocal abuse

(6,

29) . Others, too, found that frequent partner physical aggression was bidirectional rather than men only or women only

(30) . Thus, we classified the relationship, rather than the individual, as clinically abusive but with the expectation of studying empirically whether the physical consequences for women outweigh those for men

(31) . A measure of each study member’s experience as perpetrator and victim was obtained by using the Conflict Tactics Scales

(32) .

We identified 38 women and 37 men who met criteria for clinical abuse because they endorsed one or more abuse consequences on the Partner Conflict Calendar (for details, see reference 6). Of these, 68% of the women and 60% of the men reported being injured (sprains, bruises, cuts, loss of consciousness, broken bones, loose teeth), 24% of the women and 3% of the men had an injury requiring medical attention, 24% of the men and women reported that the police were called, 3% of the women and no men reported using a shelter, and court records showed that 15% of the men and no women had an official domestic violence conviction. This group of 75 individuals experienced abuse lasting 5 months, on average, in the past 3 years (range=1–32 months).

Of particular importance to the present investigation of mental health consequences of abuse, the men in the clinical abuse group reported being victimized by the same mean number of acts at the hands of their partners as did the women in the group. On the Conflict Tactics Scales

(32), both the men and the women in the clinical abuse group reported more victimization experiences than other cohort members of their sex. The effect size for this difference was 1.51 SDs more victimization on the Conflict Tactics Scales for men in clinically abusive relationships (t=9.60, df=454, p<0.001) and 1.63 SDs more victimization for the women (t=10.77, df=447, p<0.001). Furthermore, the men and women in the clinical abuse group did not differ from each other on mean scores on the victimization scale (effect size=0.12 SDs) (t=0.25, df=73, p>0.10). Both men and women in the clinical abuse group also reported perpetrating significantly more physical abuse compared to the rest of the cohort (men: effect size=1.36 SDs) (t=8.47, df=455, p<0.001) (women: effect size=1.29 SDs) (t=8.20, df=447, p<0.001). Men and women in the clinical abuse group did not differ from each other on their mean perpetration scale scores (effect size=0.10 SDs) (t=0.19, df=73, p>0.10). Thus, the 38 women and 37 men in clinically abusive relationships on the Partner Conflict Calendar were involved in abuse to the same extreme extent, whether as perpetrator or as victim, and moreover, they scored the most extreme of all cohort members on the Conflict Tactics Scales abuse measure, thereby validating the Partner Conflict Calendar’s identification of serious abusive relationships.