Impairment in odor naming, as measured by the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT)

(1), has been reported in patients with a first episode of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder

(2) . However, the clinical significance of this olfactory identification deficit and the relevance of the UPSIT to clinical practice are less clear.

The use of the UPSIT results to identify clinically relevant subgroups has been examined in a study with patients at “ultra-high risk” of developing a psychotic disorder

(3) . When followed prospectively, the patients who eventually developed a psychotic illness had poorer premorbid UPSIT performance than those who developed other psychiatric disorders or who remained well.

In the current study, first-episode patients with psychosis who had not previously received antipsychotic medications were studied. UPSIT scores, measured shortly after the onset of treatment, were examined in relation to remission of symptoms after 1 year of treatment.

Method

Fifty-eight antipsychotic-drug-naive patients were recruited as they entered the Nova Scotia Early Psychosis Program, where they received clinical care based on best-practice standards

(4) . Written informed consent was obtained. Exclusion criteria included head injury with a loss of consciousness exceeding 5 minutes, nasal or facial fracture, and current rhinitis or sinusitis.

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

(5) was given by trained raters (with an interrater reliability of 0.8 or greater) at baseline (a drug-naive state) and after patients had received 1 year of treatment. A five-factor model of the PANSS was used

(6) . The factors were positive (P1, P3, P5, P6, G9), negative (N1, N2, N3, N4, N6, G7, G12), cognitive/disorganized (P2, N5, N7, G11, G12, G13, G15), anxiety/depression (G1, G2, G3, G4, G6), and excitement (P4, P7, G8, G14).

The subjects were tested with the UPSIT

(1), which is composed of 40 cards, each containing a scratch-activated scent-impregnated patch and four possible answers. All subjects had a normal olfactory threshold, as assessed by the compound phenyl ethyl alcohol (score: mean=9.3, SD=2.6, normal range=8–11; unpublished data of Good et al.).

Olfactory assessment was carried out as soon as it was judged that the subject could participate without direct interference from psychotic symptoms. On average, this occurred 4 weeks after treatment initiation. Olfactory performance appears to be unaffected by exposure to antipsychotic medications

(7) .

Symptom remission for each PANSS-derived factor was defined as no item within the factor rated as more severe than a 3 (mild)

(6,

8) . With PANSS ratings at 1 year for each factor, remitted and nonremitted groups were identified. Note that this criterion for remission, while identifying patients with persistent symptoms, does not assess treatment response, defined as a change in symptom severity.

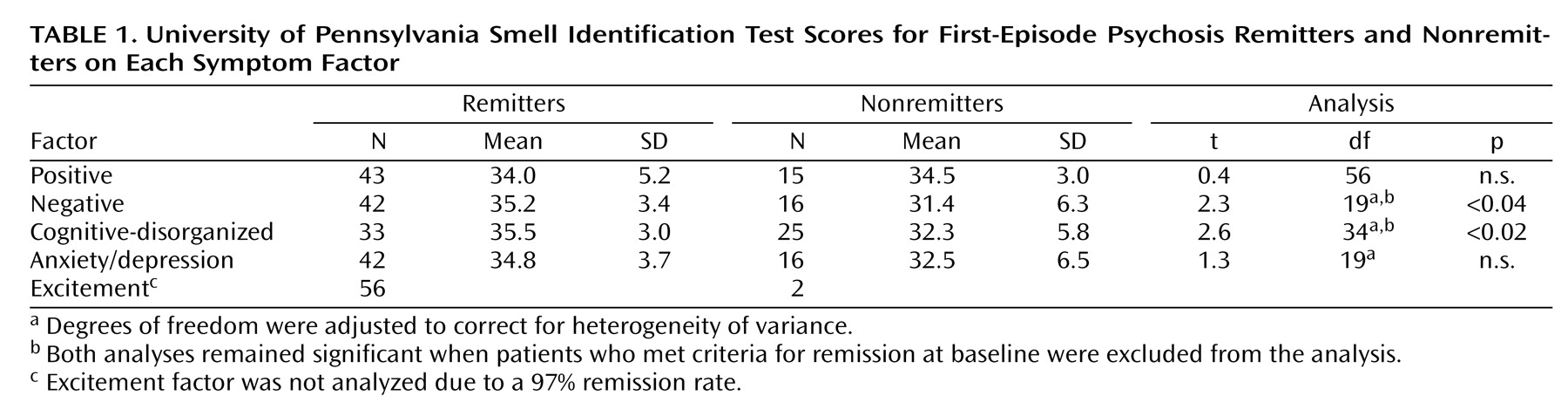

For each factor, the remitted and nonremitted groups were compared on baseline UPSIT scores with independent t tests (with correction for heterogeneity of variance where applicable). The excitement factor was not analyzed due to a 97% remission rate.

Results

The 58 patients (18 women, 40 men) were a mean age of 22.5 years (SD=4.7). After 1 year, 75% (N=44) met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and the remainder were diagnosed with psychosis not otherwise specified. The mean baseline UPSIT score was 34.1 (SD=4.7). After we used standardization data (1), 31% (N=18) were considered microsmatic (UPSIT score <34 of 40).

When we compared baseline olfactory test scores, they revealed no differences between remitters and nonremitters based on positive (n.s.) or anxiety/depression (n.s.) symptoms (

Table 1 ).

The patients who met remission criteria for the negative symptom factor had significantly higher olfactory test scores than those who did not (p<0.04), as did patients who met criteria for remission on the cognitive/disorganized factor (p<0.02) (

Table 1 ).

Because status at baseline may have influenced the results of the 1-year analysis, the patients who met criteria for remission at baseline were excluded, and the same analyses were conducted. The results were identical to those observed by examining the total group.

The patients were also stratified based on olfactory status. For the patients who were normosmatic, 80% (N=32) had remission of negative symptoms, and 68% (N=27) had remission on cognitive/disorganized symptoms. Among microsmatic patients, the corresponding remission rates were lower: 56% (N=10) and 33% (N=6), respectively. Remission groups did not differ in terms of baseline symptom severity, except that negative symptom remitters had less severe baseline negative symptoms.

Discussion

The results highlight the clinical utility of assessing patients for olfactory identification deficits early in the course of a psychotic disorder. Olfactory identification deficits appear to serve as one marker for a subtype of patients who are characterized by less frequent remission of negative and cognitive/disorganized symptoms. In contrast, the UPSIT results were not predictive of persistent positive or anxiety/depression symptoms.

It is beyond the scope of this study to determine the relative importance of the UPSIT for other variables, including the duration of untreated psychosis, premorbid adjustment, and affective flattening

(9) that may characterize patients with enduring negative symptoms. Larger groups are needed to support meaningful multivariate analysis, and such a study is currently under way in our center.

In the field of schizophrenia spectrum disorders research, few easily measured behavioral markers exist. Olfactory performance, as measured at the first episode by the UPSIT, clearly warrants further study.