A previous suicide attempt is a powerful predictor of future suicidal acts

(12,

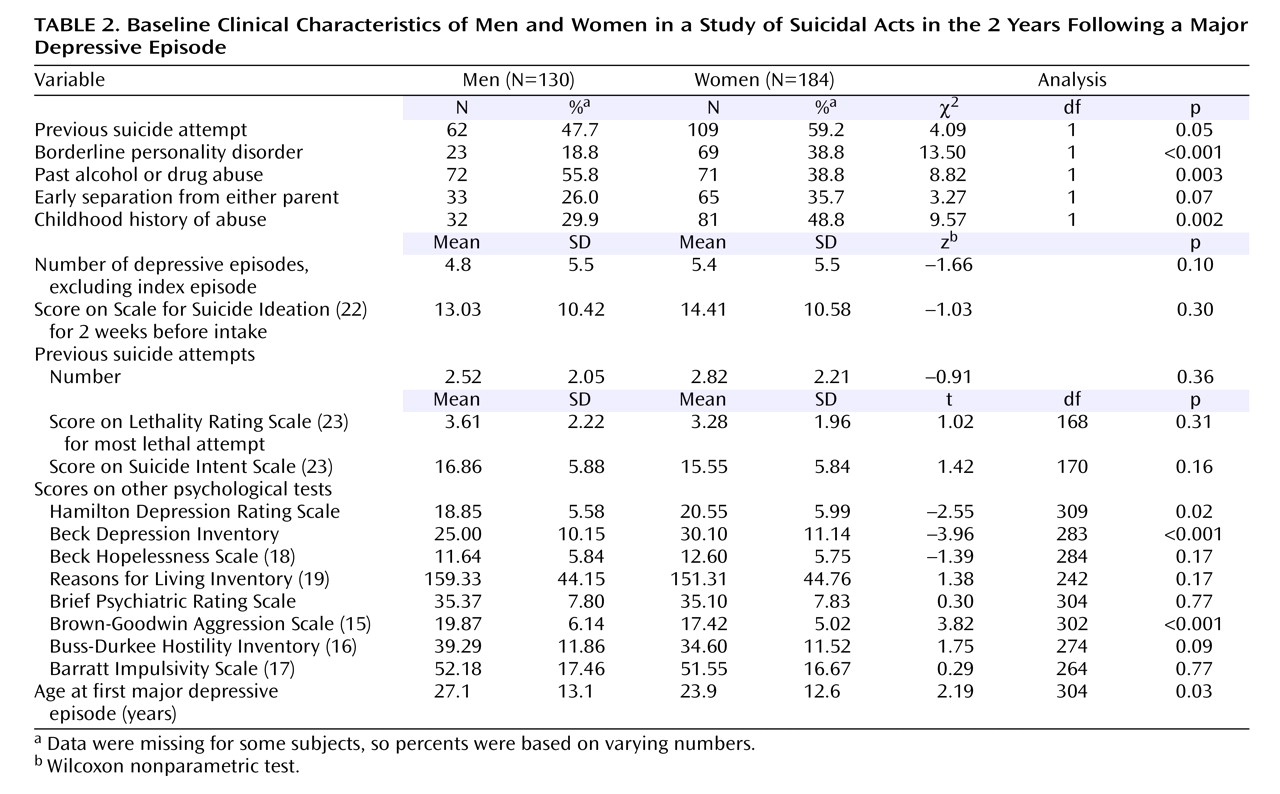

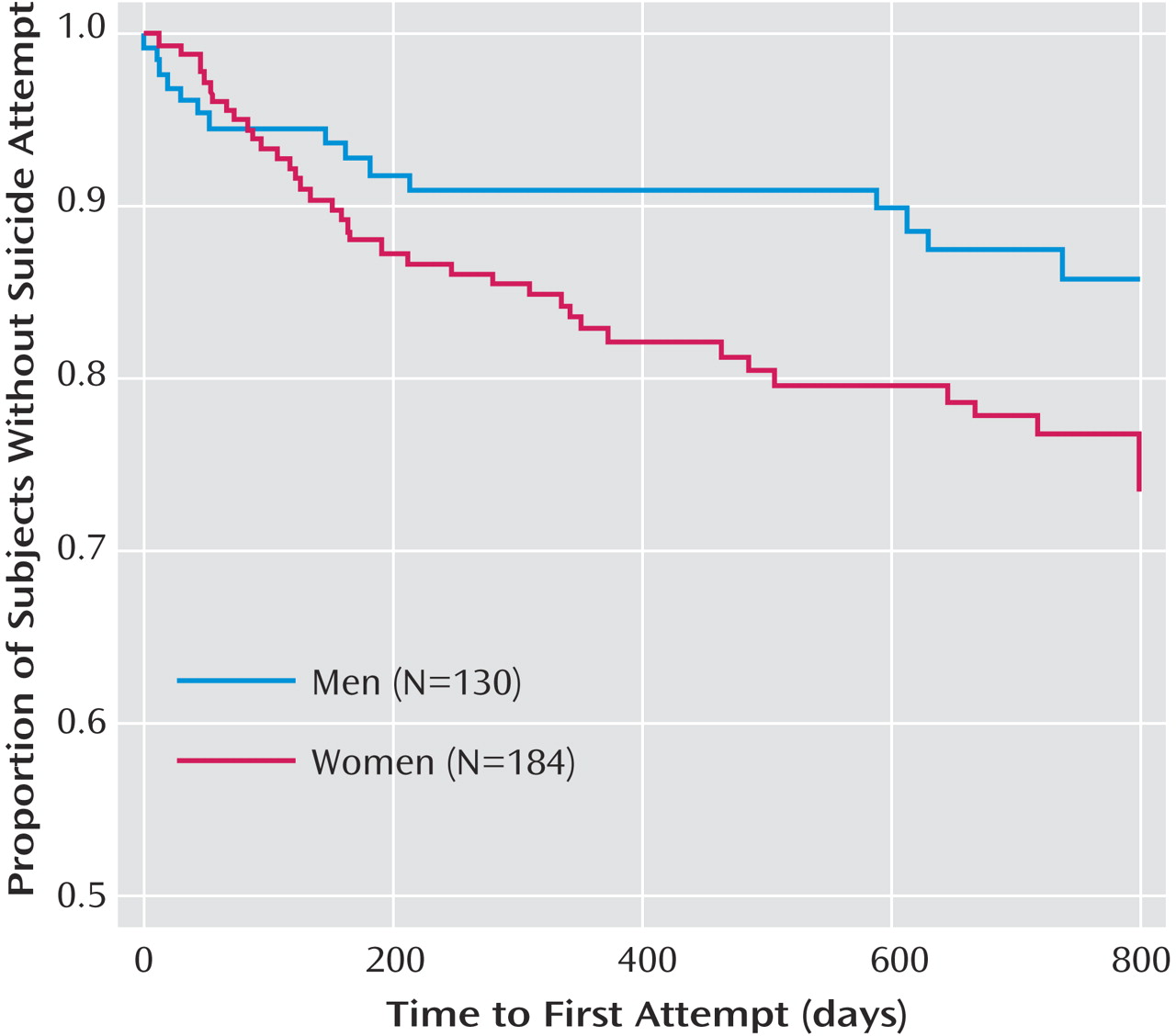

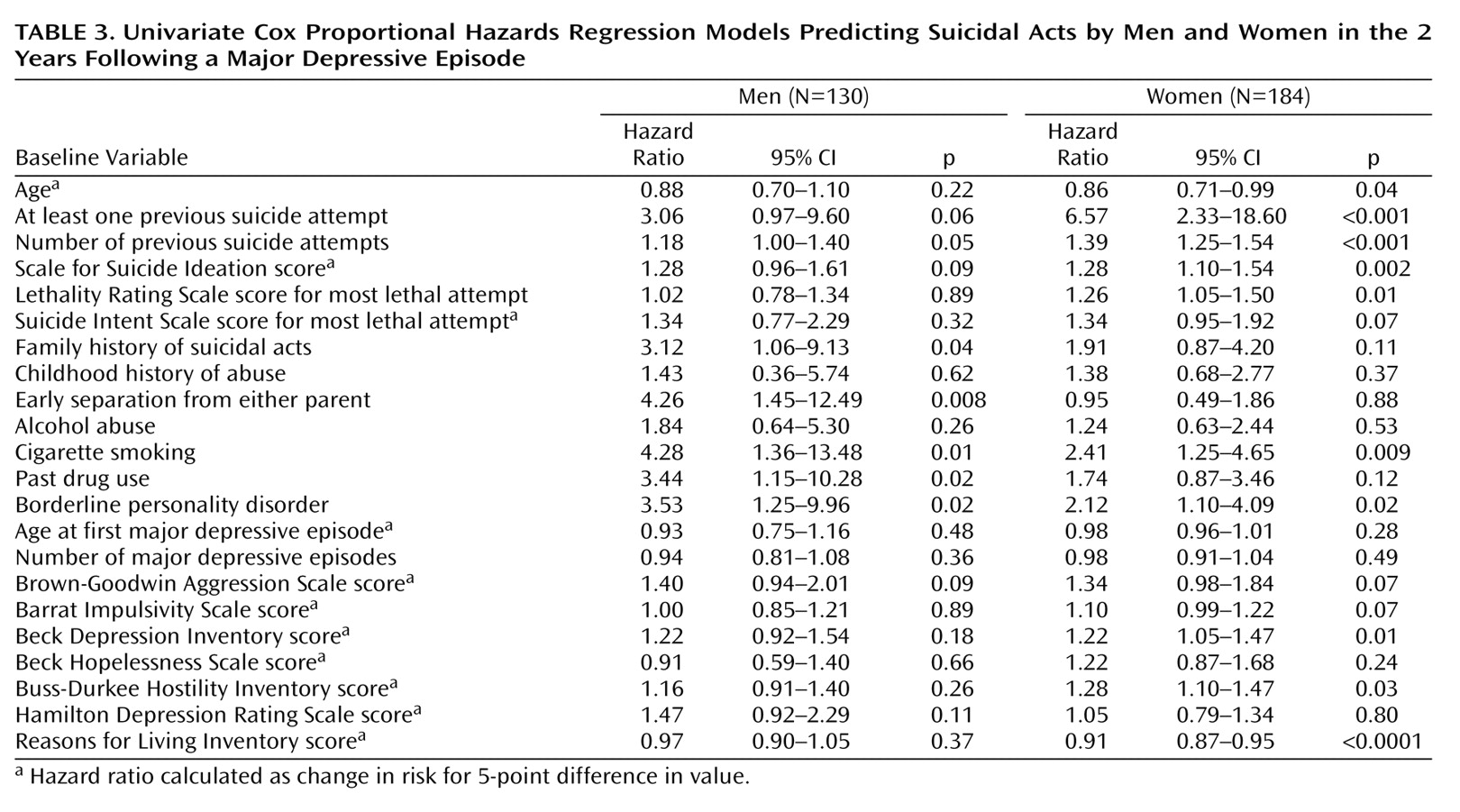

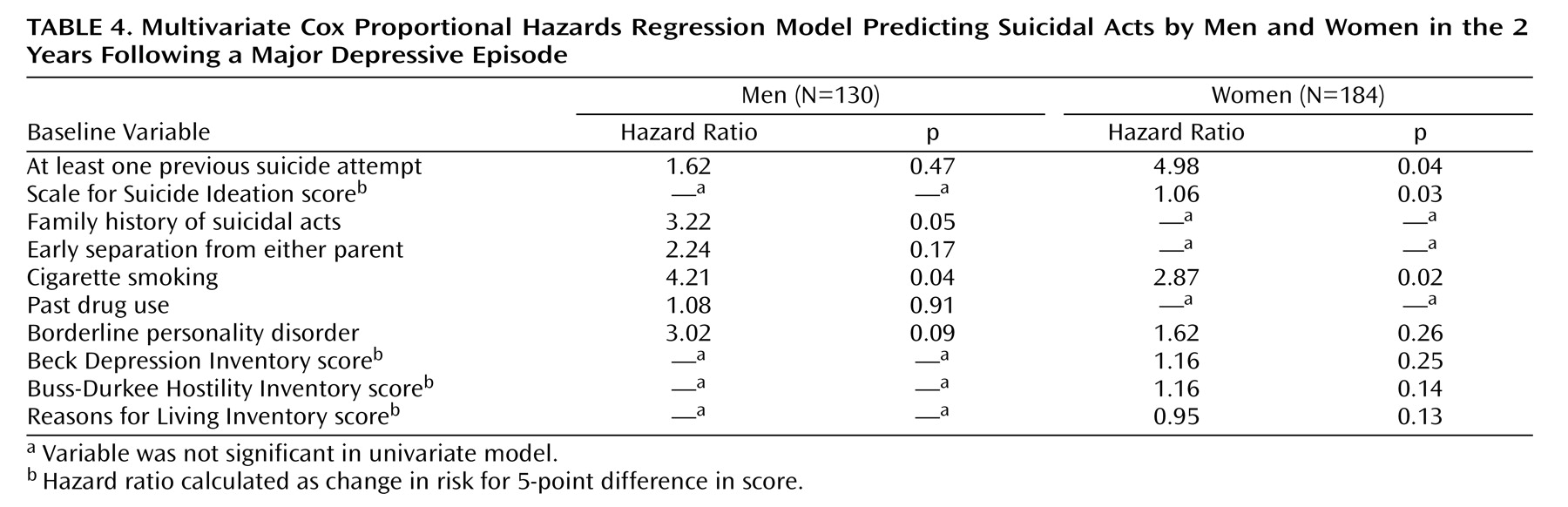

24) . In this study, men with past suicidal behavior had a threefold, but nonsignificantly, greater risk for future attempts. Women had a significant, sixfold higher risk of a future suicide attempt if they had made past attempts. The large effect among depressed women may be due to the earlier onset of depression among women, perhaps hampering the development of coping skills and rendering them more vulnerable to suicidal behavior. Alternatively, because men often use more lethal means than women, they may be more likely to die as a consequence of suicidal behavior, thus skewing clinical groups toward men with fewer, less lethal attempts.

Risk Factors for Men

Substance abuse has been reported to predict suicide attempts and completed suicide by people with mood disorders in general

(25) . In this study group, past drug abuse predicted suicidal behavior in men only, a finding that is consistent with the observation that suicide deaths among men frequently occur within the context of substance use disorders

(26) . Drug and alcohol misuse may predispose men to suicidal behavior in the setting of disruptions in important relationships

(26) . Whether disinhibition

(11), serotonergic dysfunction

(11) due to drug abuse, interpersonal factors, or a combination of these mediate the effect of drug abuse on future risk in men requires further study.

We expected aggression and hostility to affect future suicidal behavior in men. Our data suggest a 7% increase in risk for future suicidal acts for each point on the aggression scale, but the finding did not reach significance, nor did hostility predict suicidal acts. Although in this group, men reported more aggressive behavior than women, perhaps more aggressive depressed men at risk for suicidal acts do not seek treatment. We do not have data to address this possibility. Nonetheless, it has been noted that anger at oneself predicts suicidal ideation, not acts, in young men living in the community

(8) . The relationship between anger at oneself and aggression is likely to be complex.

Family history of suicidal acts tripled the risk of future suicidal acts only for the men in our study. Suicidal behaviors cluster in families

(27), independent of the transmission of psychiatric conditions

(28) . A large epidemiologic study

(29) showed that a family history of psychiatric disorders increased the risk for suicide completion in both sexes, but it indicated a more robust effect of familial suicide on females than males. Whether family history affects males and females differently is unknown but could be related to genetic contributions from X-linked genes or mitochondrial DNA or differences in child rearing between the sexes. Moreover, the heritability of suicide attempts and completions in the two sexes may differ, resulting in these apparently contradictory results.

For men, early parental separation increased the risk of suicidal acts more than threefold. Early parental loss is a risk factor for suicide in adolescents and young adults regardless of sex

(30,

31) . One retrospective study

(32) demonstrated that early loss, separation, or inadequate child rearing in young men was more strongly associated with death by suicide than with death from car accidents. Differential effects by sex may relate to genetic or rearing differences; perhaps girls can attach to new caretakers more easily in the absence of a parent.

Multivariate analyses uncovered that among depressed men, the predictive power of several of the variables could be explained by their relationship to the increased risk ascribable to cigarette smoking. This finding underscores the need for studies that have comprehensive clinical assessments so that such relationships can be uncovered, leading to accurate predictive models for suicidal behavior.

Risk Factors for Women

We hypothesized that women with more subjective depression, fewer perceived reasons for living, borderline personality disorder, or a history of childhood abuse would be more likely to engage in future suicidal behavior. Except for childhood abuse, these factors were predictive in univariate analyses. Each point increase on the BDI increased the risk for suicidal acts in women by 4%. We previously reported that subjective depression severity is a risk factor for suicidal acts

(12) . Several studies have examined the predictive capacity of depressive subtype

(33 –

36), but none has focused on sex differences. The 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey

(37) found that, compared to women with natural deaths, women who completed suicide had endorsed depressive symptoms at all ages; however, depression was only a factor among older male suicide victims, implying that other conditions, such as alcoholism or substance abuse, are associated with suicide in younger men, such as those included in our study group (mean age=38 years), and that depression as a risk factor for suicide by men appears later in life.

There was an inverse relationship between risk for suicidal behavior and scores on the Reasons for Living Inventory for women. Women may attach more importance to their responsibilities toward children, an important factor assessed by the Reasons for Living Inventory. Studies show that being married is protective for men, whereas having a child under the age of 2 is protective for women

(10,

29,

38) . Among women, the protective effect of marriage against suicide has been attributed to the effect of having children

(38,

39) .

For women, the number of previous suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, lethality of prior attempts, and hostility all increased the risk for suicidal acts. Each previous suicide attempt increased the risk of subsequent attempts by over 30%. These findings are consistent with the findings from two prospective studies, in which women who committed suicide had previously attempted suicide but men had not

(7,

9) . Indeed, despite the similarity between men and women in the levels of suicidal intent, women’s use of less lethal means may result in more frequent survival of attempts.

Several

(40 –

42), but not all

(12,

43), prospective studies have implicated suicidal ideation as a risk factor for future suicidal acts. Some cross-sectional studies showed greater suicidal ideation in female teens

(44,

45), while others showed no sex differences in suicidal ideation, despite higher prevalences of suicidal behavior in women, younger persons, those living alone, and women in urban areas

(46) . Thus, the predictive capacity of suicidal ideation requires further study.

We found that in women, for each increment in medical damage from the most lethal attempt, future suicidal risk increased by 26%, suggesting that lethality and frequency of suicidal behavior are related in women. This is of concern in light of reports that the proportions of men and women who make medically serious suicide attempts are similar despite the fact that twice as many women use nonlethal methods

(47) . Examining the medical consequences of attempts made by women may help guide assessment of risk for future suicidal acts.

For women, greater hostility increased the risk for a suicidal act. Hostility in association with depression has been linked to suicidal behavior

(11,

48), although why it should be predictive for women only is not clear. As mentioned previously, it is possible that more aggressive, hostile men at risk are not represented in clinical samples.

As was the case among men, multivariate analyses revealed that some of the predictive variables found in the univariate analyses owed their robustness to their association with other variables. Among women, past suicidal behavior explained the effect of borderline personality disorder on the future risk of suicidal acts. The complexity of finding appropriate predictors for rare events cannot be overstated.

Risk Factors Affecting Men and Women

We predicted that borderline personality disorder would increase the risk for suicidal acts in women. However, it also increased the risk for depressed men. Men and women with both major depression and borderline personality disorder have more suicide attempts and objective planning than do those with either diagnosis alone

(49) . This was the case for the subjects in this study: 81% of the patients with borderline personality disorder had previous attempts. Among the female subjects, a history of suicide attempts accounted for the predictive power of borderline personality disorder. However, for men, the predictive power of borderline personality disorder was only partially explained by previous attempts. An association between “sensitive/brittle” personality and later suicide in depressed men but not women has been reported

(7,

9) . Brittleness and sensitivity are perhaps more typical of narcissistic personality disorder but may also be consistent with borderline personality disorder. Although borderline personality disorder is less often diagnosed in men, its presence alongside depression may pose incremental risk for future suicidal behavior.

The only other risk factor that significantly predicted future suicidal behavior in both sexes was cigarette smoking. Cigarette smoking increases the risk for suicidal acts

(12,

41,

50) independent of the effects of major depression, alcohol abuse, or drug use

(51), and smokers are reported to have more aggressive or impulsive behaviors. Current smokers but not former smokers

(52) have lower monoamine oxidase activity, which may result in serotonergic dysregulation, mediating the association of cigarette smoking with depression and suicide

(11) .

Limitations

The inclusion of individuals treated at a university clinic and exclusion of current substance and alcohol users hamper the generalizability of our findings. For example, the exclusion of current substance abusers may explain our finding that aggression and hostility do not predict suicidal behavior in men. We followed the patients for 2 years only, although this is the period of highest risk for suicidal acts. The naturalistic design means that potentially relevant variables, such as the intensity of antidepressant treatment, presence of treatment refractoriness, and the time-varying nature of depressive symptoms, cannot be addressed.

Another limitation is that the statistical analyses to assess sex differences in the hazard ratios by using interaction terms (variable by sex) showed that the interaction terms lacked statistical significance, except in the case of parental separation. These results are reflected in the overlap in confidence intervals for the hazard ratio for women compared to men. It is possible that the smaller number of subjects and fewer future suicidal acts among men led to large differences in the hazard ratio estimates with wide confidence intervals for the two sexes, thus leading to nonsignificant differences. However, we think it is useful to document the hazard ratios within each sex because the order of importance of the individual risk factors differs in men and women. Moreover, in the multivariate models, while previous suicide attempts is an independent predictor for women, among men it is not driving the risk, just “standing in” for other factors.

From a clinical standpoint, the relative lack of protection afforded by reasons for living in men, compared to women, is notable. Furthermore, despite the well-documented fact that men are at greater risk for completed suicide, depressed female suicide attempters appear at relatively greater risk for repeated suicidal behavior. Thus, clinical evaluation may be enhanced by considering the difference between the sexes in the importance of risk factors for suicidal acts.