Diagnostic Agreement

To evaluate the accuracy of diagnoses, we calculated kappa reliability coefficients

(18) to compare the gold standard diagnoses to the routine diagnoses, SCID diagnoses, and SCID-plus-chart diagnoses, respectively. Kappa coefficients represent the amount of agreement between pairs of ratings (e.g., agreement on a diagnosis five out of 10 times) adjusted for chance agreement. Chance is based on the likelihood that a specific diagnosis will occur in a sample. For example, if in a sample of 100 patients, 50 have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, a rater is going to be correct at least 50% of the time if he or she arbitrarily gives everybody a diagnosis of schizophrenia. When the base rate of a specific diagnosis is high in a sample of patients, the chance of being accurate in giving that diagnosis will also be high. Kappa subtracts the percentage of agreement (agreements divided by the total number of comparisons) from the probability of agreement by chance. This offers a less biased estimate of agreement.

The comparisons of the gold standard and the other diagnoses were conducted at three levels of diagnostic specificity. Level 1 was the most specific, and level 3 was the least specific. Level 1 required that the gold standard diagnosis match exactly with the others on core diagnosis (e.g., bipolar disorder) but not the subtype (e.g., most recent episode manic, depressed, or mixed). It was not required that the diagnoses match on whether the major depressive disorder was a single episode or recurrent, on the specific subtype of schizophrenia, on the specific drug type in substance abuse, or on the symptom or feature type for organic mental disorders or adjustment disorders. In addition, discriminations between substance abuse and dependence were not required at level 1.

At level 2, diagnoses that shared symptoms, and therefore could be easily confused with one another, were grouped together (i.e., less precision in diagnosis was required). Major depressive disorder, depression not otherwise specified, and dysthymia were grouped together as depressive disorders. Bipolar disorders (I, II, and not otherwise specified) and cyclothymia constituted a second grouping. Generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, and social phobia were combined under anxiety disorders. All other diagnoses were grouped the same as for level 1. At this second level of analysis, diagnoses were considered in agreement if they fell within a grouping. For example, panic disorder and OCD were considered a match at level 2, just as major depressive disorder and dysthymia were considered a match at level 2.

At level 3, more global categories were created, requiring even less precision in diagnoses than at level 2. Depressive disorders and bipolar disorders were grouped together under mood disorders. All psychotic disorders were grouped together with the exception of schizoaffective disorder, which stood alone. All other groupings were the same as for level 2. To be considered a match, agreement only within the broad diagnostic groupings was required. For example, major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder were considered a match at level 3, just as schizophrenia and delusional disorder were considered a match at level 3.

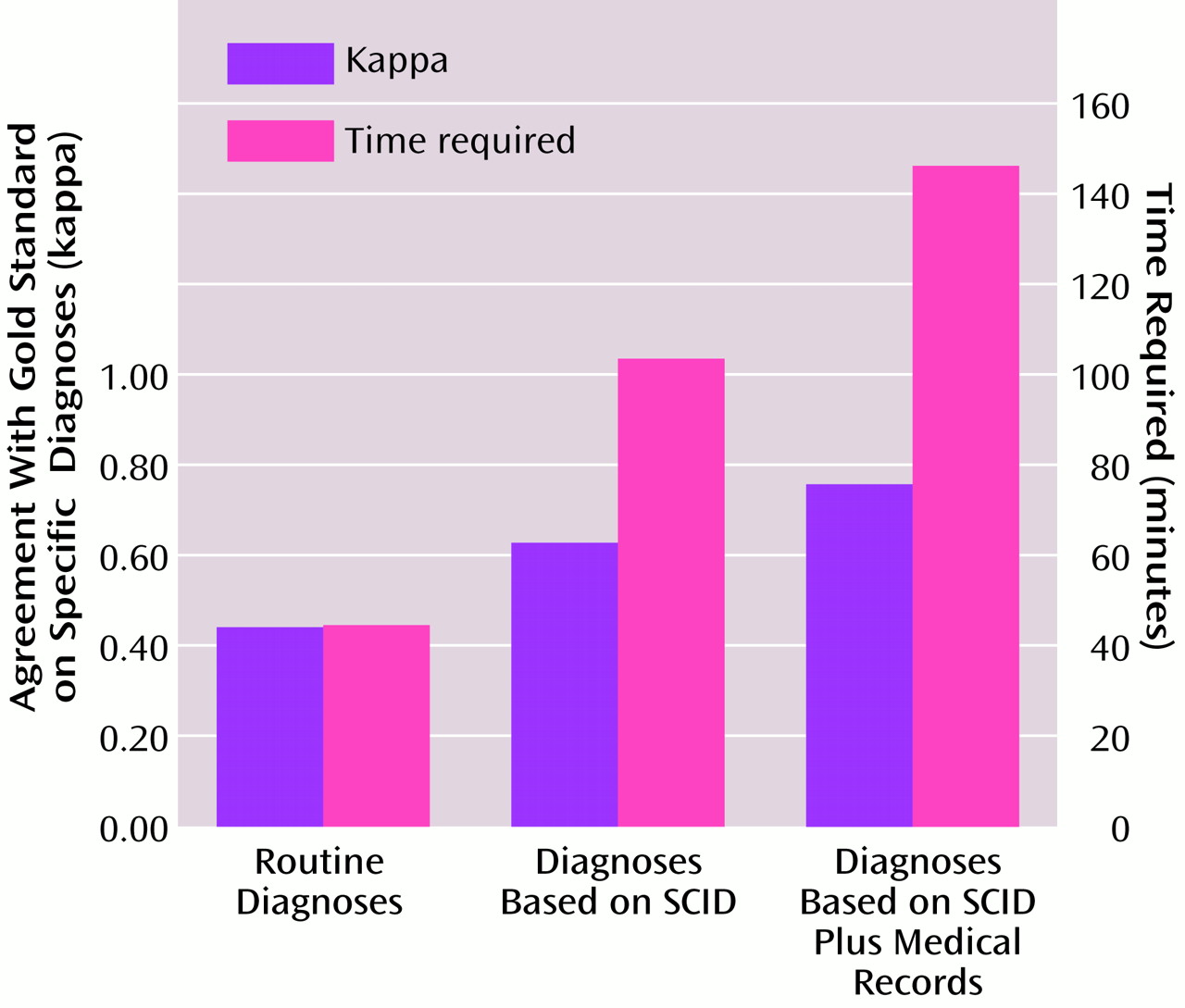

A comparison of gold standard diagnoses with the clinic psychiatrists’ routine diagnoses based on standard interview practices revealed levels of agreement for the total sample as follows: level 1, kappa=0.45; level 2, kappa=0.51; and level 3, kappa=0.52. As less precision was required, the amount of agreement between diagnoses increased. In an examination of kappa coefficients for subsamples of diagnostic groups containing at least nine patients, the routine diagnoses were most accurate for schizophrenia, which had kappa values from 0.59 to 0.69, and least accurate for schizoaffective disorder, with a kappa of 0.46 across levels 1–3.

In the comparison of the gold standard to the diagnoses derived by the study nurses using the SCID only, the kappa reliability coefficients for the total sample were 0.61 (level 1), 0.64 (level 2), and 0.64 (level 3). SCID diagnoses were also most accurate for schizophrenia, with a kappa of 0.72, and least accurate for schizoaffective disorder, with a kappa of 0.57.

To assess the relative importance of adding the medical record review to the diagnostic process, kappa coefficients were calculated for the comparison of the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses to the gold standard diagnoses. The kappa values were 0.76 (level 1), 0.76 (level 2), and 0.78 (level 3) for the total sample. The diagnoses were most accurate for schizophrenia, with a kappa of 0.87, and least accurate for depression, with kappas from 0.76 to 0.81 across levels 1–3.

There were no differences in kappa coefficients between male and female patients in any of the comparisons. For the comparison of the gold standard and the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses, there were no differences in kappa values by racial group. For the comparison of the gold standard and routine diagnoses, there were no differences at level 1; however, at levels 2 and 3, the kappa coefficients were lower for Caucasians (0.47 and 0.49, respectively) than for non-Caucasians (0.57 and 0.59, respectively). These differences were not due to differences in group size or in chance agreement.

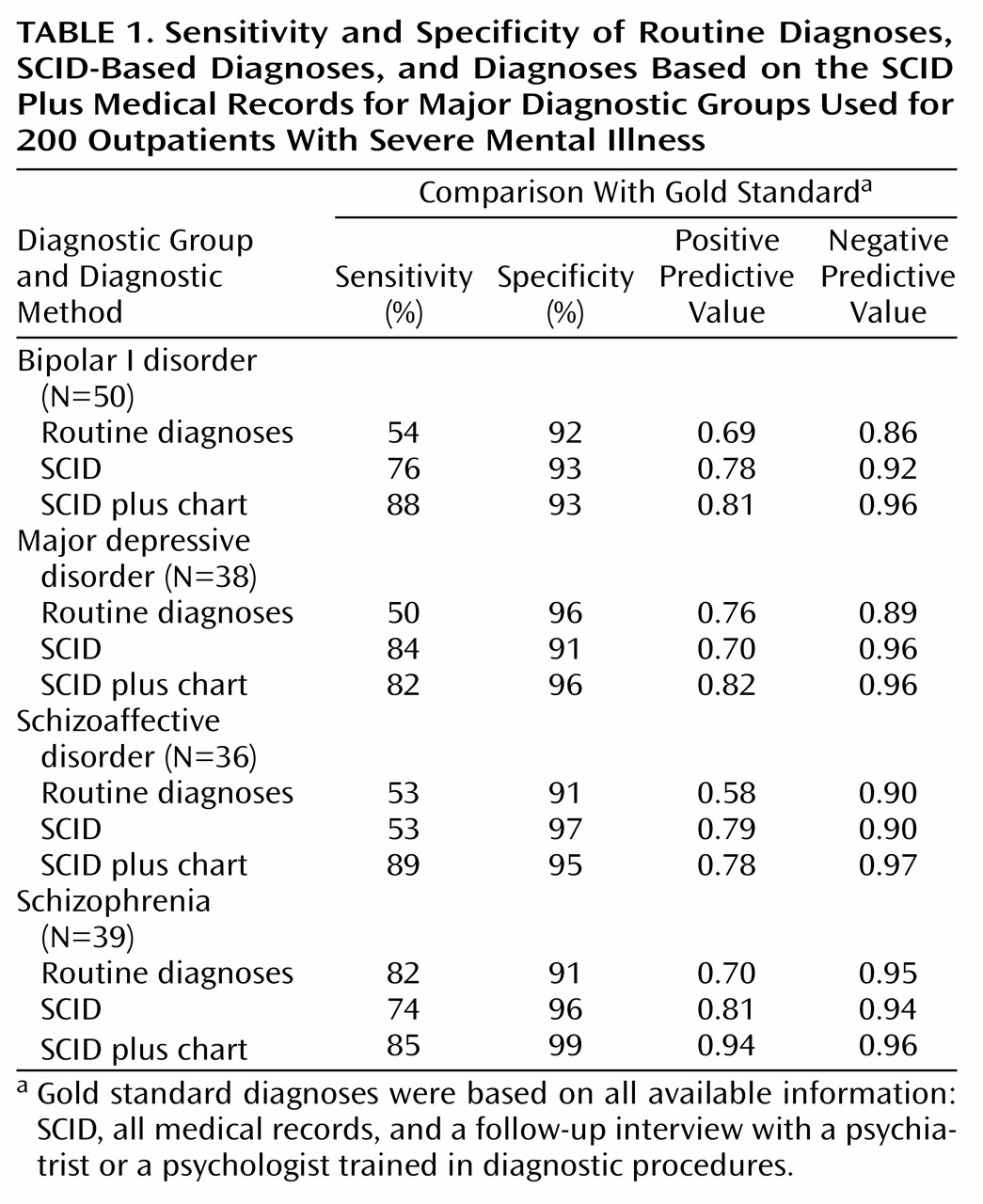

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value and negative predictive value for the four major diagnostic groups at each step in the diagnostic process are presented in

Table 1. Relative to the gold standard diagnoses, the sensitivity and specificity of the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses were generally superior to those of the routine diagnoses and the SCID alone. In particular, use of the SCID plus medical records substantially improved the detection of mood disorders and schizoaffective disorder over clinic procedures, while maintaining a high level of accuracy. Note that sensitivity and specificity analyses do not adjust for chance agreement and, therefore, inflate performance levels.

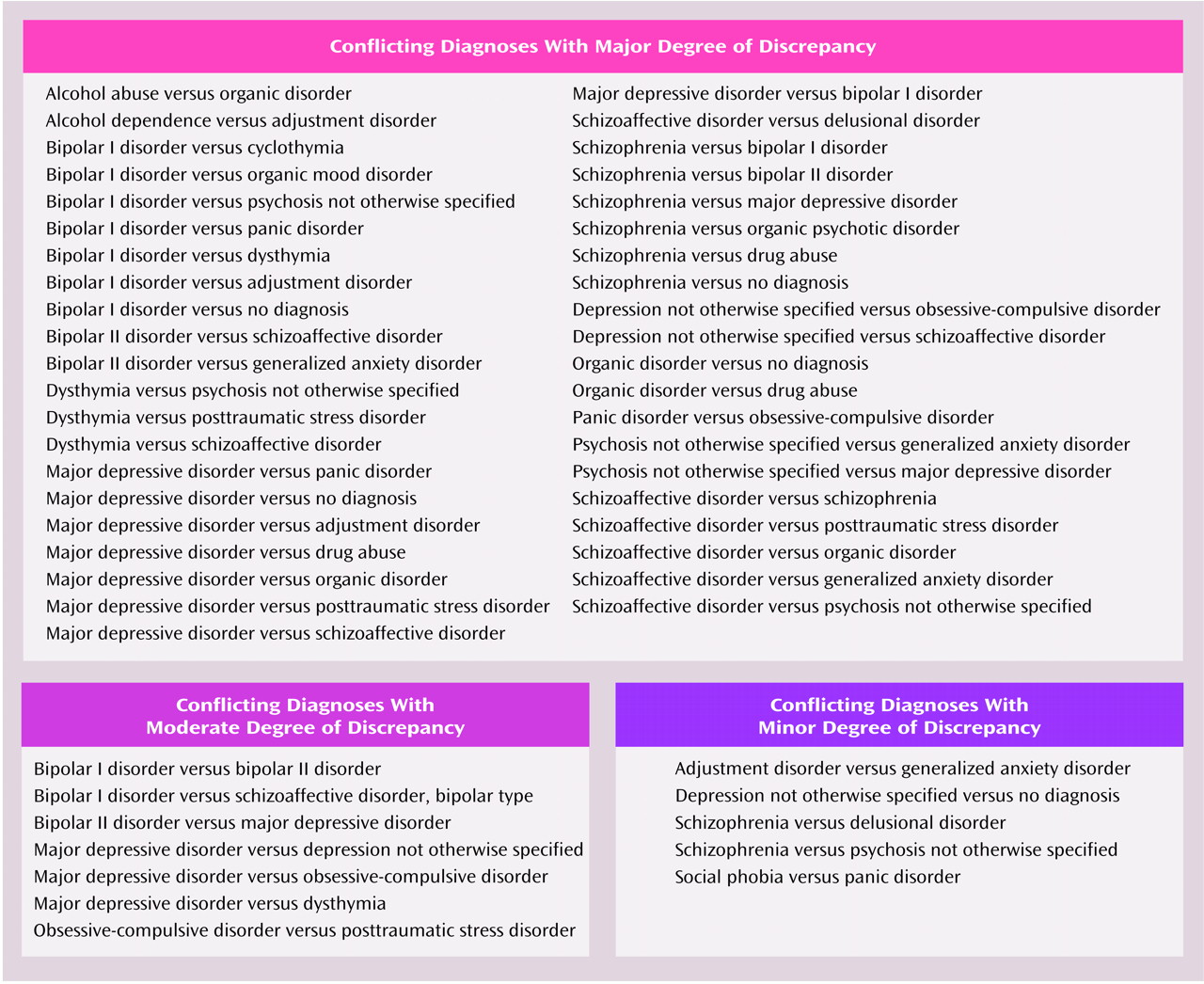

To evaluate the clinical importance of the diagnostic disagreements, each was categorized as a major, moderate, or minor discrepancy (

Figure 1). Diagnostic disagreements were defined as major if the differences would imply different pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatment strategies or different prognoses or would influence the decision to seek additional general medical evaluations. Moderate discrepancies were those in which the treatment indications would not differ as dramatically as for the major category and additional diagnostic workups would not be indicated. Minor discrepancies were those in which treatment plans would not be likely to change much or at all despite diagnostic differences. The majority of the diagnostic differences between the routine diagnoses and the gold standard (64 of 94, 68%), between the SCID and the gold standard (51 of 65, 78%), and between the SCID-plus-chart method and the gold standard (30 of 43, 70%) were considered major discrepancies. Of the remaining diagnostic disagreements, 29% of the routine diagnoses (N=27), 17% of those based on the SCID (N=11), and 23% of those based on the SCID plus medical chart (N=10) were considered moderate discrepancies with the gold standard.