Even though both reviews considered studies that almost exclusively consisted of hospitalized populations, subsequent authors, all citing Guze and Robins, have generalized their 15% figure to populations neither Guze and Robins

(1) nor Goodwin and Jamison

(2) considered. Following this convention, major American textbooks continue to report the 15% figure as correct for all depressed patients

(3–

7). Moreover, “depression” is no longer defined as it was in 1970. Subsequent editions of DSM have made the diagnosis of a major depressive episode more inclusive. Today up to 20% of the population meet criteria for a watered-down, broad, and, ultimately, a less lethal depressive diagnosis. Klein and Thase

(8) made this point powerfully when they observed that in 1972, the lifetime prevalence of depression in the American population in DSM-II terms was 2%–3%, when the definition of depression included only involutional melancholia, the unipolar form of manic depression, psychotic depression, and “severe depressive neuroses.” By 1994, under the rubric of DSM-IV, the lifetime prevalence of depression had increased to 10%–20%. The major difference between 1972 and 1999 is not that we are caught in an affective epidemic. “Much broader and more inclusive definitions of mood disturbance, with major differences in thresholds for ‘clinical depression’ and when we recommend treatment” are the explanation

(9). Today, many more people carry a depressive label, but the incidence of the severe forms remains relatively low.

Method

Our reexamination began with a reanalysis of the data in the 17 studies included in the meta-analysis of Guze and Robins

(1). For each study, we compared both proportionate mortality and case fatality. The additional 13 studies that Goodwin and Jamison

(2) used to confirm the findings of Guze and Robins

(1) were also reanalyzed. We also conducted a computer search of the MEDLINE (1966–present) and PsycINFO (1984–present) databases and reviewed the bibliographies of relevant psychiatry textbook chapters, studies, and review articles to identify additional studies. The search was limited to English-language studies.

The purpose of our study was to reassess the lifetime prevalence of suicide in patients with affective disorders. All studies analyzed in this article are, by definition, survivorship studies, and most are observational rather than randomized and controlled. O’Brien and Shampo

(13) stated that “in every study of survivorship, the first requirement is to describe the group studied.” Thus, we have only included those reports containing a minimum data set that summarized the number of suicides and deaths among a cohort of affectively ill patients. Each included study plainly indicated whether the subjects at the inception of the investigation were inpatients, outpatients, or a mixture of both.

We chose the general and inclusive term “affective disorders” because it encompasses the incongruence among investigators

(12) as well as the definitional heterogeneity bred over the past several decades by the evolution of classification systems such as DSM and ICD. Many studies predated or ignored these systems. The jumble of terms for affective disorders included manic depression, bipolar depression, neurotic depression, nonpsychotic depression, reactive depression, endogenous depression, neurosis, involutional melancholia, unipolar depression, primary depression, secondary depression, and affective psychosis. Adding to the confusion was the fact that some authors are of the opinion that the presence of endogenous features, rather than depressive subtype, determines suicide rates

(14,

15).

Over 30 years ago, Silverman

(16) determined that suicide in depressed patients was not clearly associated with the presence or absence of physical symptoms, diagnostic subtype, psychosis, or treatment modality. The search for definitive suicide risk factors, detailed in hundreds, if not thousands, of papers, remains inconclusive. Among psychotropic medications, only lithium has been found to reduce the incidence of suicide

(17) and then only after patients have reliably taken it for at least 2 years

(18).

This study scrutinized each population’s treatment status, since we hypothesized that different patient statuses have different suicide rates. First, we confirmed that the studies included in the two previous reviews

(1,

2) almost exclusively contained inpatient subjects. As new studies were identified, we took special pains to distinguish how patients were classified for comparison purposes. The new studies of affective disorder patients were sorted into two inpatient categories and one outpatient category on the basis of how the authors classified patient status at study commencement

(19). The first inpatient category was undifferentiated according to suicidality; the second comprised patients hospitalized after suicidal ideation or attempt.

After noting treatment status, we restricted the studies accepted by excluding studies that did not have a mean follow-up time of at least 2 years, since the incidence of suicide is elevated in the first 2 years after hospitalization

(20–

23). In addition, all studies included had to have at least a 90% rate of follow-up. This restriction was based on the common sense presumption that the larger the number of original subjects unaccounted for, the greater the number who may have been lost to a condition like suicide

(11,

24). As more subjects are lost to follow-up, more questions must be raised about what happened to them and what conclusions can be drawn with confidence from the remaining data

(25).

While we took great pains to obtain the cleanest collection of studies possible, several problems presented themselves. First, the suicidal inpatient category contained mixed diagnoses, since only two of the studies specifically excluded all but affective disorder patients. Second, few outpatient studies could meet our initial rigid inclusion criteria. Most studies began with a mix of patients from a variety of psychiatric services, including inpatient, outpatient, emergency room, and day hospital. In one study, 54% had a history of prior hospitalization, and 86% had been hospitalized at least once during the 5-year follow-up period

(26). The largest American study of mortality in psychiatric “outpatients,” Morrison’s San Diego study of 12,000 patients, was, in fact, a report of a mixed group

(27). More than 40% of these so-called “outpatients” had at least one hospitalization during the 8.5 years of the study (J.R. Morrison, personal communication, 1999). As a result, we relaxed the outpatient category criteria to include studies in which at least two-thirds of the subjects were nominal outpatients at the starting point.

Another potential limitation of this study, and of the two previous reviews

(1,

2) as well, arises from the failure to consider additional factors that may influence suicide risk. For instance, while the discrepancy between male and female suicide rates in the general population is significantly narrowed in the psychiatric population, it is not completely erased

(28). While some studies distinguished between the sexes, others simply provided the number of patients followed. Other potential risk factors surely exist for which data are not generally available. These may include rehospitalization, treatment modalities, employment, age, race, country, or any of the myriad other factors that can be used to characterize populations.

Like the two previous reviews

(1,

2), our study used a small set of variables from each study to examine the risk of suicide in affective disorder patients. Our data analysis considered only the number of patients, the number of deaths, and the number of suicides in each of the studies we analyzed. It would have been preferable to collect the survival status and length of follow-up for each subject, but those data were not universally available. Our analysis included as suicides only those deaths classified specifically as such and excluded accidental deaths, “quasi-suicides,” and other categories of ambiguous deaths. This narrow suicide definition only slightly diminishes suicide counts. Coroners over the last century have been shown to apply consistent standards to suicide classification

(29) and to underestimate suicide by exclusion of accidental deaths and the like at a consistent rate of 15%–20%

(30).

Like the two previous reviews

(1,

2), ours is a meta-analysis, an approach “developed as a way to summarize the results of different research studies of related problems”

(31). Admittedly, many difficulties arise when dealing with data from such studies. The studies themselves do not fully reflect the situation in the population at large

(32–

36). Further, the various studies differ in their aims and in their execution

(37). While it was impossible to completely overcome these limitations, we were able to minimize their impact by carefully delineating the terms and conditions for inclusion.

Statistical methods can compensate for the remaining heterogeneity. These methods are often referred to as “random effects models”

(38) as opposed to “fixed effects models,” which do not account for study-to-study variability. The idea behind random effects techniques is that some universal set of studies exists, from which the observed studies are randomly drawn. This construct has the effect of ascribing study-to-study variability to this unobserved sampling mechanism. The global estimates of probabilities or averages obtained by using random effects models are usually approximately equal to the quantities that are calculated by using traditional techniques. However, the variance estimates are larger, which reflects the additional study-to-study variability.

In this article, we calculated four distinct probability estimates for each of five different populations of psychiatric patients (affective disorder outpatients, affective disorder inpatients, suicidal inpatients, and the hospitalized affective disorder patients from the two previous meta-analyses [

1,

2]). The first probability estimate is the “case fatality prevalence,” or the probability that a subject will die by suicide during the course of the study. Within a single study, this can be estimated by dividing the number of suicides by the number of subjects. The second probability is the “proportionate mortality prevalence,” or the probability that a subject will die as a result of suicide given that the subject will die during the course of the study. This corresponds to the rates used in the two previous meta-analyses

(1,

2). For a single study, this can be estimated by dividing the number of suicides by the number of deaths. The third probability represents the “general mortality prevalence,” or the probability that a subject will die of any cause during follow-up. For a single study, this probability can be estimated by the ratio of total deaths to total subjects. The fourth probability is a projection of what the suicide mortality would be if all subjects were followed until death. It is obtained by an application of Bayes’s Rule, which states that the probability of suicide is equal to the probability of suicide, given death, times the probability of death

(39).

Each of the first three probabilities, and its 95% confidence interval, was calculated by using the generalized estimating equations

(40) capabilities found in PROC GENMOD, a part of the SAS statistical package

(41). The suicide mortality estimate was calculated as the product of the proportionate mortality prevalence and the general mortality prevalence. In addition to obtaining probability estimates, pair-wise comparisons among the various mortality prevalence estimates were performed, again by using PROC GENMOD.

Results

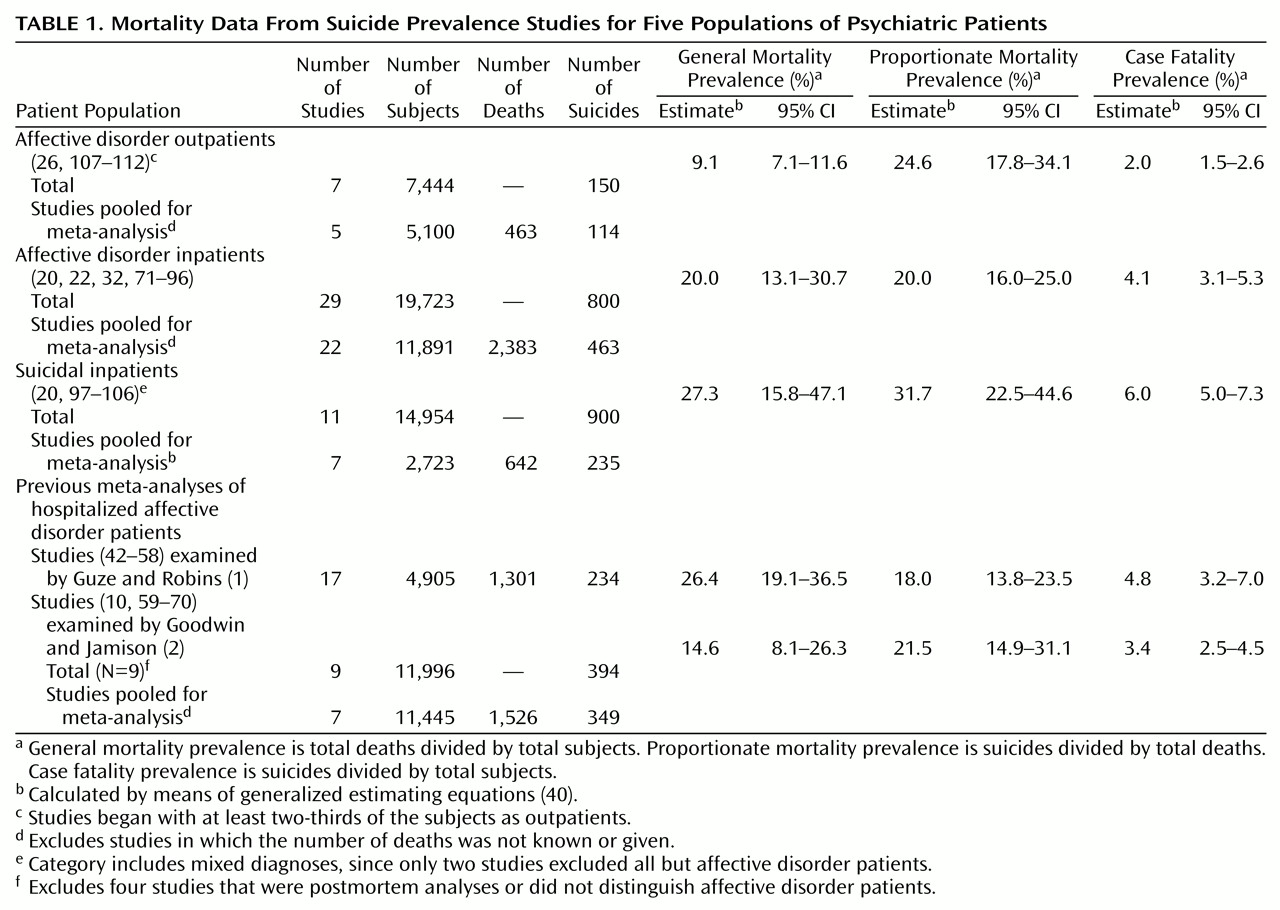

Table 1 summarizes the data obtained from the studies belonging to each of our five populations of psychiatric patients. One group reflects the 17 studies

(42–

58) originally examined by Guze and Robins

(1). Another represents the 13 studies

(10,

59–

70) in Goodwin and Jamison’s review

(2). The other three groups were those we identified for this study. Twenty-nine studies

(20,

22,

32,

71–

96) met inclusion criteria for the “affective disorder inpatients” category. Eleven studies

(20,

97–

106) focused specifically on inpatients hospitalized after a suicide attempt or ideation. Seven studies of affective disorder patients

(26,

107–

112) began with at least two-thirds of the subjects as outpatients. The information recorded for each group of studies includes the number of studies that could be pooled in our meta-analysis as well as the total number of subjects, deaths, and suicides in each collection of pooled studies. It also contains the random effects estimates of the general mortality prevalence, proportionate mortality prevalence, and case fatality prevalence rates, along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The group-wide general mortality estimates varied from 9.1% to 27.3% among the different populations of psychiatric patients. The estimates of proportionate mortality ranged from 18.0% to 24.6% for four of the groups, with that for suicidal inpatients equal to 31.7%. The case fatality estimates were considerably smaller, ranging from 2.0% for affective disorder outpatients to 6.0% for suicidal inpatients. The case fatality estimates nearly matched the final estimates of suicide risk we obtained by applying Bayes’s Rule to the probability estimates obtained from the random effects models (

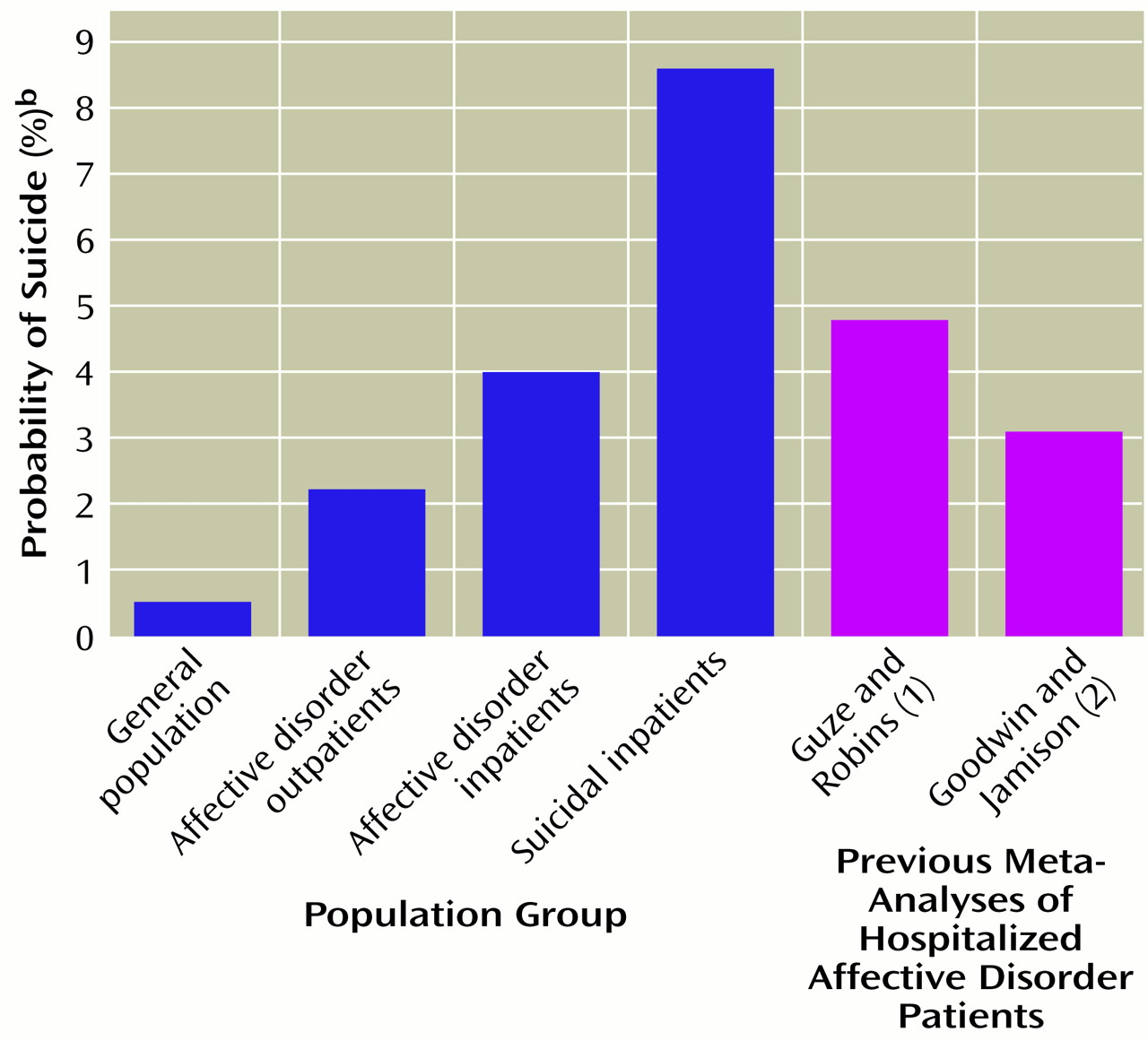

Figure 1).

The case fatality rates of all of the three populations of psychiatric patients for which we identified new studies were significantly different from one another. The case fatality prevalence of affective disorder inpatients significantly differed from that of both suicidal inpatients (χ

2=5.40, df=1, p=0.02) and affective disorder outpatients (χ

2=12.87, df=1, p=0.0003). Also, the case fatality prevalence of the affective disorder outpatients and the suicidal inpatients significantly differed (χ

2=43.84, df=1, p<0.0001). As we expected, the earlier studies collected by Guze and Robins

(1) and Goodwin and Jamison

(2) were most similar to our new collection of studies of affective disorder inpatients. The case fatality prevalence from Guze and Robins was significantly different from that of our affective disorder outpatients (χ

2=12.73, df=1, p=0.0004) but was not statistically different from that of Goodwin and Jamison (χ

2=1.91, df=1, p<0.17) or from our affective disorder (χ

2=0.42, df=1, p<0.52) or suicidal (χ

2=1.15, df=1, p<0.29) inpatients. While not different from that of Guze and Robins

(1), the case fatality prevalence from Goodwin and Jamison

(2) significantly differed from those of both affective disorder outpatients (χ

2=6.36, df=1, p<0.02) and suicidal inpatients (χ

2=10.58, df=1, p<0.002). These results support our hypothesis that suicide risk is hierarchical among the affectively ill.

Discussion

This study was a meta-analysis that drew upon data pooled from diverse sources. Even with the crudeness of the data, however, two points emerge robustly. First, case fatality rates are a better measure of suicide risk than proportionate mortality rates. Second, lifetime suicide prevalence sorts out in a stair-step hierarchy of increasing risk according to treatment history (

Figure 1).

We are not the first to argue that case fatality rates describe suicide risk better than proportionate mortality rates. In a 1968

American Journal of Psychiatry review on the epidemiology of depression

(16), Silverman roundly criticized the use of proportionate mortality to describe suicide risk in an earlier meta-analysis of Robins and associates

(113).

The proportionate mortality measure reflects only the percentage of suicides among those who died during the study, and that is its weakness. It estimates a conditional probability: the risk of a suicide should death occur during the study. It cannot approximate the actual risk of suicide unless at least one of two conditions is met: either all of the subjects under observation are followed until they die or suicides occur at the same rate relative to the total number of deaths.

The first of these conditions is difficult to meet. Many subjects in a given study are likely to outlive the career of a single researcher. For instance, Helgason’s 1979 paper followed a cohort for 61 years

(10), and almost one-half of the cohort was still alive at the end of this extensive follow-up period.

The second requirement does not fit what we know about suicide epidemiology. Suicide is overrepresented in youthful populations

(11). Further, numerous researchers have demonstrated that suicide occurs variably at different points in the natural course of affective illness

(20,

23,

114–

117). It is evident that suicide risk decreases as the time from the most recent hospitalization, or treatment, increases

(20,

114–

116,

118). Also, suicide risk is highest during the years immediately following the onset of affective disorders

(23,

117,

119).

Because the risk of suicide is not constant across the history of affective disease, proportionate mortality must provide a biased estimate of suicide risk. This is particularly true for studies with a short length of follow-up in which very few patients have yet died from any cause. With suicide concentrated in the first months after discharge, and in the early stages of disease, it will be disproportionately represented in a suicide-to-death ratio. This is reflected in the results of the studies we examined. Studies with a short length of follow-up produced estimates of proportionate mortality that were very high. In fact, the proportionate mortality prevalence estimates from two studies, one with a mean follow-up of 3.2 years

(76) and one with a mean follow-up of 0.5 years

(44), were equal to 100%

(44,

76). Case fatality estimates do not suffer from this bias, since they allow individuals who have not yet died to provide information concerning the probability of suicide during follow-up. Of course, we must acknowledge that case fatality prevalence will underestimate the lifetime rate of suicide by missing future suicides. However, proportionate mortality prevalence misses not only future suicides but also future deaths. As suicides tend to occur at a higher rate soon after diagnosis or treatment, the bias in case fatality estimates is sure to be smaller than the bias incurred by using proportionate mortality prevalence to estimate lifetime suicide risk.

As a final evaluation of the appropriateness of case fatality and proportionate mortality methods, consider the results presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. The case fatality prevalence estimates are quite close to our final estimates of suicide risk, while the proportionate mortality prevalence estimates are much higher. While neither proportionate mortality prevalence nor case fatality prevalence is a perfect estimate of suicide risk, from this combined evidence, it would appear that case fatality is better.

If case fatality rates are used to approximate suicide risk, a hierarchical layering of suicide risk becomes apparent. The results in

Table 1 suggest, and pair-wise comparisons verify, that suicide prevalence differs according to treatment history. Those who are not psychiatric patients have the lowest risk. Psychiatric outpatients have a higher risk, but it is not so great as that of psychiatric inpatients. In turn, psychiatric inpatients who are suicidal have the highest risk. While we must recognize that only two of the 11 studies of suicidal inpatients specifically concerned affective disorder patients, these had two of the four highest case fatality prevalences, at 9.2%

(99) and 15.2%

(104). This points to greater lethality in the affective subgroup. Clinical judgment about the level of treatment intensity required appears to predict suicide prevalence.

Others before us have recognized this hierarchy. Black and Winokur

(120) asserted that hospitalized psychiatric patients form “a special subgroup” whose elevated death risk early after discharge “may not be generalizable.” Moreover, Kiloh and colleagues

(88) found that in the long-term outcome of depressive illness, “few factors apart from prior hospital admission seem to be of prognostic importance.” A number of studies that included one or more types of psychiatric patients, as well as nonpsychiatric subjects, provided further evidence that our proposed hierarchy is correct

(10,

34,

67,

121,

122). These studies consistently demonstrate that those who are deemed to be the most severely ill at baseline are at the greatest risk for suicide. They complement the finding of VanGastel and colleagues

(123), who reported that both suicidal ideation and attempt are directly related to the severity of depression.

Given that a suicide risk hierarchy is present, we now recall that the studies included in the meta-analyses of both Guze and Robins

(1) and Goodwin and Jamison

(2) almost exclusively consisted of inpatients. Subsequent authors, including those in most major English-language textbooks, who have referenced the seminal Guze and Robins meta-analysis, have extrapolated the results to

all patients with affective disorders. In most cases they have failed to acknowledge the preponderance of inpatients in the original studies. This consequent bias cannot be ignored. The case fatality prevalence estimates from the two previous meta-analyses compared favorably to that from our newly gathered inpatient collection but differed from those of outpatients. Additionally, Goodwin and Jamison’s case fatality prevalence was significantly different from the case fatality prevalence obtained from studies that examined suicidal inpatients. We emphasize that the results of the two previous meta-analyses are applicable only to patients with affective disorders who have been hospitalized without specification of suicidality.

If hospitalized depressed patients are at greater risk of suicide, what then determines which ones are hospitalized? Rather than depression itself, it is the threat of suicide that usually decides which patients are offered—or forced to accept—admission

(9,

23). The severity of depression and, hence, the degree of suicidality, may be driven by specific factors occurring along with the core depressive syndrome. These include substance abuse or dependence in the patient or first-degree relatives, anxiety (particularly the malignant anguish or “psychache” described by Shneidman

[124]), impulsivity, aggressivity, and family history of affective illness, suicide, or suicide attempts

(125). Hopelessness is pervasive in suicidal states

(126). Goldney and colleagues

(127) found that the patients in a series who died as a result of suicide after psychiatric hospitalization had more and longer hospitalizations, more previous suicide attempts, more overt depression, and more neuroleptic use. All these factors, rather than specific indicia of affective disease, will likely enter into the clinical judgment and result in some patients being admitted to the hospital while others are treated in less restrictive settings.

In summary, the case fatality method gives a more accurate accounting of suicide prevalence than the proportionate mortality method. This is because suicide risk in affective disorders concentrates early in the course of illness and soon after hospital discharge. Case fatality rates are different among groups of affective disorder patients, defined by history of treatment and suicidality. Those recently hospitalized with a suicide attempt or suicidal ideation are at highest risk. Those recently hospitalized for any psychiatric reason have the next highest risk. Psychiatric outpatients are at lower risk than inpatients but are at higher risk than those in the general population who do not carry an affective diagnosis. From a public health perspective, suicide prevention efforts should thus be focused on recently or repeatedly hospitalized patients, especially the suicidal ones. In the absence of other compelling data, it may be reasonable to relax concern somewhat as the length of time from the last hospitalization or suicidal state increases for any given patient.