The efficacy of ECT is well established for the acute treatment of depression, particularly in patients with very severe symptoms, mood-congruent delusions, prominent suicidality, and inanition and dehydration

(1–

5). Unfortunately, this population of severely ill patients remains at high risk for relapse and recurrence, even when adequate extended pharmacotherapy is provided

(6). The identification of effective continuation and maintenance strategies for these patients is a critical issue in the long-term management of depression.

Continuation therapy is often narrowly defined as treatment that occurs during the several months immediately after resolution of an acute episode of illness, with the primary purpose of relapse prevention

(7). Maintenance therapy is sometimes differentiated as a more prolonged course of intervention, extending beyond continuation therapy and used to prevent recurrence of the illness (i.e., a new episode). In practice, the distinction between continuation therapy and maintenance therapy is arbitrary

(5); what is important is that continuation therapy of some sort is necessary to prevent the return of depressive symptoms, irrespective of whether ECT or antidepressant medications are used to treat an acute episode of depression

(8).

Although the practice of extended and long-term drug therapy for depression has become standard, the use of broadly defined continuation ECT has failed to gain general acceptance

(9). Proponents of continuation ECT argue that this approach represents an effective alternative or adjunct to drug treatment in selected patients who are at high risk of relapse. This group includes patients who have demonstrated response of their acute episode to a standard course of ECT and 1) have experienced an acute episode that was refractory to drugs, 2) have relapsed during long-term pharmacological treatment, or 3) have had contraindications to long-term antidepressant or thymoleptic drug treatment

(7,

10,

11). The published literature on continuation ECT consists mainly of case reports

(12–

15), naturalistic studies

(8,

16), and retrospective case series

(11,

17–

20) of patients who clearly obtained benefit from continuation ECT. We are aware of no prospective or randomized studies, and only three reports have included some form of controlled comparison, even if retrospective

(11,

16,

18).

The present retrospective case-controlled study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of continuation ECT plus long-term antidepressant treatment versus long-term antidepressant treatment alone in a large sample of patients with severe chronic depression treated under naturalistic conditions. Before beginning long-term treatment of any sort, all patients had responded positively to a standard course of ECT given for an acute episode of illness. Both within- and between-subjects comparisons were used, and outcome measures corresponded to those used in previous reports

(12). Clinical and demographic factors were evaluated with respect to their ability to predict outcome. On the basis of the published literature, we hypothesized that continuation ECT combined with long-term antidepressant treatment would be superior to standard treatment with long-term antidepressants alone in these severely ill patients.

Method

Patients

To determine patients’ eligibility for the study, we reviewed the charts of all patients who received continuation ECT from April 1985 to July 1999 in the ECT Program at Butler Hospital, a university-affiliated psychiatric facility in Providence, R.I. Continuation ECT patients with a primary DSM-III, DSM-III-R, or DSM-IV axis I diagnosis of either major depression (unipolar) or bipolar I or bipolar II disorder (most recent episode depressed) were enrolled (continuation ECT group). Excluded were continuation ECT patients who 1) had severe concurrent medical illness, 2) had a preexisting nonaffective psychiatric illness, or 3) met criteria for schizoaffective disorder. This protocol was reviewed by the Butler Hospital institutional review board and judged to be exempt from the requirement for written informed consent.

A comparison group consisting of patients given long-term antidepressant treatment alone (antidepressant-alone group) was matched to the continuation ECT group for age, gender, primary axis I diagnosis, age at onset of depression, presence of comorbid psychosis, and year during which the index course of acute ECT was administered. Like the continuation ECT group, all patients in the antidepressant-alone group had had a positive response to acute treatment with ECT. Patients included in the antidepressant-alone group were subjected to the same inclusion/exclusion criteria as the continuation ECT patients. The patients in the antidepressant-alone group had received four to 15 treatments of acute ECT for their depressive episode. After acute ECT, these patients were continued or maintained with antidepressant medications alone, without additional ECT, for prevention of relapse and recurrence.

Additional data on demographic and clinical characteristics were abstracted from all patients’ charts. Additional demographic characteristics included ethnicity, marital status, and employment history. Ancillary clinical characteristics included secondary axis I diagnoses, any axis II diagnoses, bipolar versus unipolar subtype, family history of affective disorder in first-degree relatives, age at onset of depressive symptoms, age at first ECT, age at index ECT, medications administered during the index depressive episode (including number, duration of trials, and doses of antidepressants, neuroleptics, thymoleptics, and anxiolytics), number and duration of hospitalizations, and the use of psychotherapy. Clinical information suggestive of greater severity (psychosis, severe suicidality, and melancholia)

(7,

16,

21) was noted. The method of electrode placement (unilateral versus bilateral) and mean seizure duration were determined.

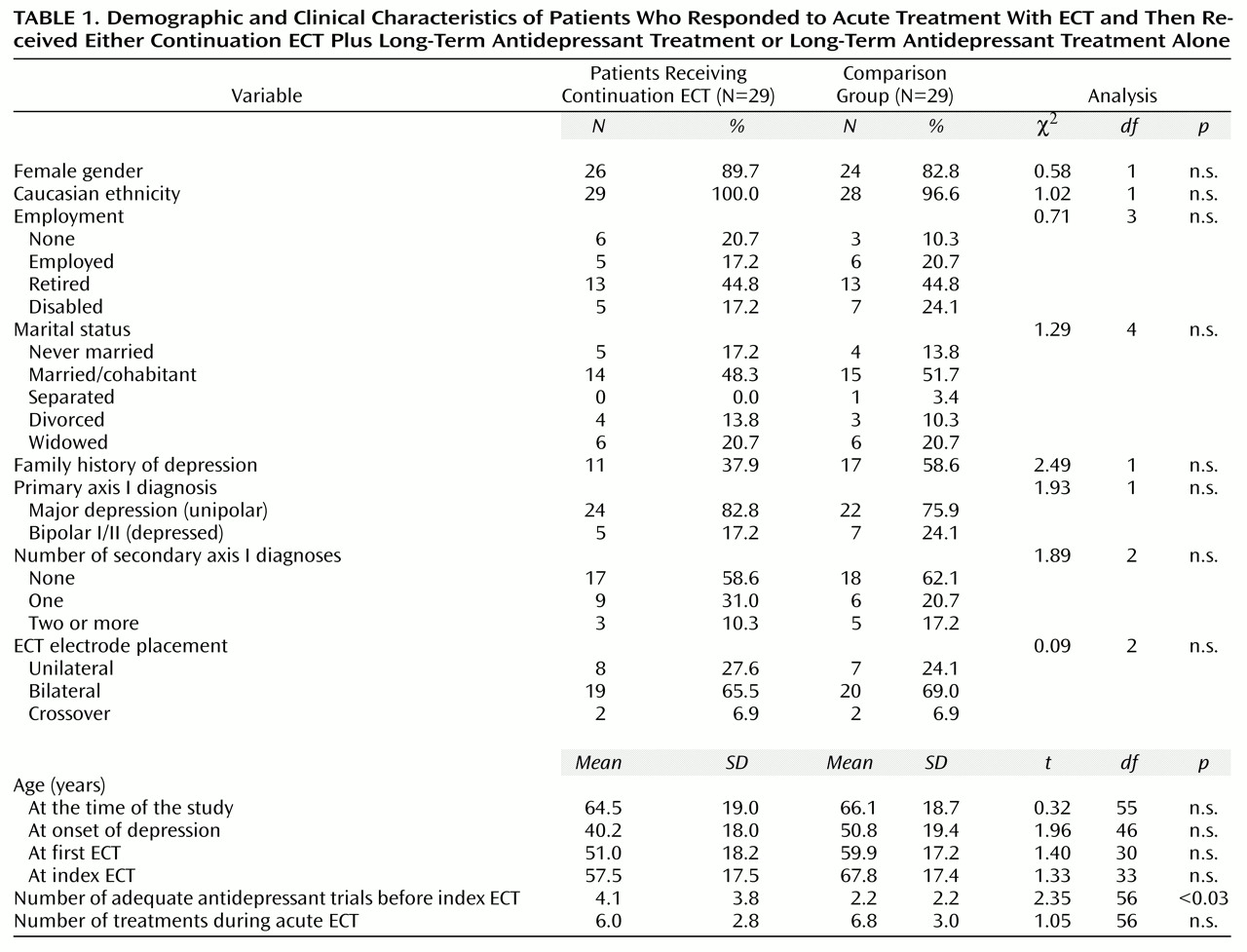

A total of 58 patients were included in the study, 29 in the continuation ECT group and 29 in the antidepressant-alone comparison group. The mean age of the continuation ECT patients at the time of the study was 64.5 years (SD=19.0, range=29–91) and that of the antidepressant-alone patients was 66.1 years (SD=18.7, range=34–96). Both groups were predominantly (>80%) female and appeared similar in terms of socioeconomic background and ethnicity (

Table 1).

After the course of acute ECT, 28 (96.6%) of 29 continuation ECT patients and all of the antidepressant-alone patients were managed with antidepressant medications. One continuation ECT patient received no psychotropic medication during the course of continuation ECT. A comparably broad range of agents was used in both groups, including tricyclics (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, nortriptyline), heterocyclics (amoxapine, bupropion, venlafaxine), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (phenelzine, tranylcypromine), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (sertraline, fluoxetine, paroxetine), and serotonin receptor antagonists (nefazodone, trazodone). Patients with bipolar disorder in both groups received mood stabilizers (carbamazepine, lithium, divalproex), and a similar proportion of psychotic patients in both groups received neuroleptics. No patients with bipolar disorder were maintained with antidepressants without a mood stabilizer. Drug doses were generally in accepted therapeutic ranges and were similar between treatment groups.

ECT Treatment

ECT was administered by using a Mecta SR-1 (Mecta, Portland, Ore.) brief-pulse, constant-current device. ECT duration was considered optimal if the seizure duration (determined by observable tonic-clonic seizure) lasted 30–60 seconds. All ECT was given by a single psychiatrist (M.J.F.), who adjusted the treatment frequency on the basis of the patient’s clinical response. Patients generally received ECT for acute episodes at a rate of two to three treatments/week until a positive clinical response occurred, on the basis of the consensus evaluation of M.J.F. and the referring psychiatrist that the core depressive symptoms necessitating hospital admission were much or very much improved. The decision to institute continuation ECT was similarly based on the clinical consensus of M.J.F. and the referring psychiatrist that medication maintenance alone was unlikely to be effective given the patient’s history of treatment response and most recent clinical presentation. If the patient continued with ECT, treatments generally were delivered weekly for the first month, every 2 weeks for the following month, and then monthly.

Study Design and Methods

This retrospective study evaluated the efficacy of continuation ECT by comparing the outcomes of patients who received this treatment combined with long-term antidepressant treatment (continuation ECT group) with those of matched comparison patients who received long-term antidepressant treatment alone (antidepressant-alone group). Both groups had manifested a positive response to acute treatment with ECT just before entering the period of long-term treatment under study. In addition, patients in the continuation ECT group were included in a mirror-image comparison of their own clinical course during the time period immediately preceding the index episode of illness versus their course afterward.

Acute ECT was defined as a standard course of ECT administered for the acute treatment of an index episode of depression. The index ECT was the first treatment in the course of acute ECT, and it served as the reference point for calculating the major outcome variables and for the beginning of the survival analysis. Continuation ECT was defined as ongoing ECT that was administered after completion of the course of thrice weekly acute ECT, beginning with the administration of ECT on a weekly or less frequent basis.

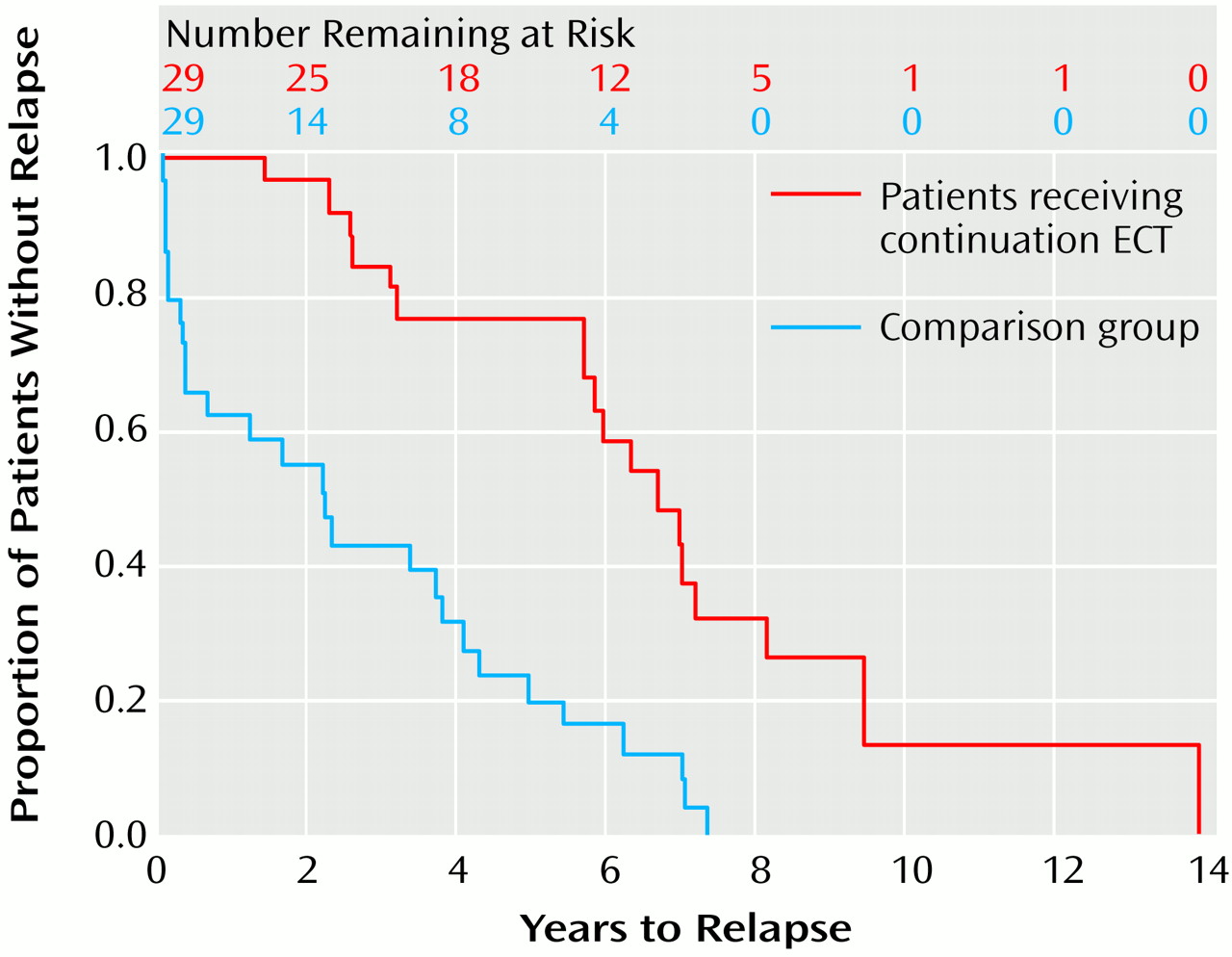

The four outcome measures of primary interest were the probability of surviving without relapse or recurrence, the time to relapse/recurrence, the frequency of hospitalization quotient, and the hospital day quotient. Probability of survival and time to relapse/recurrence were evaluated by using survival analysis, with relapse/recurrence stringently defined as the reemergence of depressive symptoms of sufficient severity to result in either rehospitalization or a new course of acute ECT. Time was counted in years from the date of the index ECT. Data from patients who did not experience relapse or recurrence during the observation period were censored. The mean duration of the observation period for all patients was 3.9 years (SD=3.1) (for continuation ECT patients, mean=5.4 years, SD=3.1; for antidepressant-alone patients, mean=2.4 years, SD=2.4).

As described elsewhere

(12), the frequency of hospitalization quotient and hospital day quotient were used to quantify the clinical history and functional status of each patient. Each variable was computed for the observation period after index ECT and for an equivalent time period preceding the index ECT. The frequency of hospitalization quotient, reflecting the average number of hospital admissions per year, was calculated by dividing the total number of admissions by the number of days in the observation period and multiplying the quotient by 365. The hospital day quotient, reflecting the average number of psychiatric inpatient hospital days, was determined in a similar manner. Both measures were calculated only for patients with an observation period ≥6 months (periods of <6 months would have resulted in artificially inflated quotients).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of clinical and demographic characteristics between groups were performed with t tests for continuous variables or contingency tables (chi-square or Fisher’s exact test) for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier product-limit method was used to estimate survival curves. Differences between the continuation ECT and antidepressant-alone groups were evaluated by using the Mantel-Cox test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to determine the significance of potential risk factors for relapse/recurrence. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with significance set at p<0.05. Analyses were performed with SPSS, version 6.1

(22).

Discussion

In this sample of chronically depressed patients responding to a standard course of acute ECT, continuation ECT in conjunction with long-term antidepressant treatment resulted in a marked improvement in clinical outcome. In comparison with rates of survival for patients who received long-term antidepressant treatment alone, rates of survival without relapse or recurrence for patients who received continuation ECT and long-term antidepressant treatment were nearly doubled (93% versus 52%) at 2 years and showed a fourfold increase (73% versus 18%) by 5 years. The mean time to relapse or recurrence more than doubled in the continuation ECT group (6.9 years versus 2.7 years for the antidepressant-alone group).

Comparison patients were closely matched with continuation ECT patients on standard demographic variables (i.e., gender and age), as well as on clinical variables (i.e., primary axis I diagnosis, age at onset of depression, the presence of comorbid psychosis), a treatment variable (i.e., positive response to an index course of ECT), and a temporal variable (i.e., year during which the index course of acute ECT was administered). As a result, patients in both groups appeared similar, as demonstrated by the lack of significant differences between groups across a broad array of clinical and treatment variables. The only significant difference detected was the greater number of previous adequate antidepressant trials in the continuation ECT group, suggesting that the depressive symptoms of these patients were more refractory to pharmacotherapy. However, neither this nor any other identified factor was related to risk of relapse/recurrence.

The follow-up period in the present study lasted more than 5 years for the continuation ECT patients, comparing favorably with the results of previous studies of continuation ECT that have employed a comparison group, none of which extended beyond a 1-year follow-up

(11,

16,

18). In this regard, it is notable that survival rates for the continuation ECT patients appeared to deteriorate appreciably between 5.5 and 7 years. It is unclear whether this decline represents a true clinical phenomenon or merely the diminished reliability of the right-hand tail of the survival curve with smaller numbers of at-risk patients

(23). For example, although the survival curve in

Figure 1 suggests that all patients in both treatment groups eventually relapsed, a marked preponderance of relapses (27 [93.1%] of 29 patients) occurred in the antidepressant-alone group; 11 (37.9%) of the 29 continuation ECT patients were censored before relapse.

In a previous study that also utilized survival analysis, Schwarz et al.

(18) detected no significant differences between continuation ECT patients and comparison patients. The lack of difference may have been due partly to the relatively short (6-month) follow-up period employed by those investigators. Surprisingly, hospitalization rates and number of hospital days, as reflected by the frequency of hospitalization quotient and hospital day quotient, respectively, proved insensitive to the effects of continuation ECT in between-groups comparisons in the present study. This finding is in contrast to the significant findings of other investigators who used these or analogous measures

(3,

16,

21,

24). Although our findings for the mean frequency of hospitalization quotient and mean hospital day quotient were similar to those previously reported, greater variance in our data precluded findings of statistically significant differences. Significant within-group decreases before and after continuation ECT were also not demonstrable, even though mean changes were in the predicted direction. Again, these results appeared to be due to marked variability and artifacts related to the manner in which the frequency of hospitalization quotient and the hospital day quotient were computed for the time period before the index ECT, even though efforts were made to minimize such artifacts. In any case, these observations underscore the importance of utilizing the more robust survival analytic techniques in subsequent research on continuation ECT.

The present findings must be considered in light of the many caveats that apply to naturalistic, retrospective studies. The sample size, although among the largest yet reported on this topic, was still modest, resulting in limited power to detect possibly meaningful differences in the clinical and demographic characteristics of the two groups. Assignment of patients to treatment groups was not random, and assessments of outcome were not blind or prospectively systematic. Diagnostic and clinical data were not derived from structured instruments and, even though the medical records were relatively complete, detailed information on patients’ clinical and functional status over time was not available. The use of hospitalization or initiation of a new course of acute ECT as measures of relapse/recurrence may have been overly stringent, resulting in an underestimation of the true relapse/recurrence rates. The relatively older age, female preponderance, and Caucasian ethnicity of the study group limit generalizability, as does the fact that all of the patients in this study demonstrated a positive response to a standard course of acute ECT before entering long-term treatment. Finally, even though treatment groups were matched on several clinical and demographic variables of obvious relevance, it is possible that other key clinical or treatment variables that were not subjected to matching or assessment may have differed between groups and may have affected outcome.

It is possible that the more favorable outcome of patients in the continuation ECT group was a result of nonbiological and nonpharmacological aspects of the different follow-up treatments. Patients who received continuation ECT were required to have direct contact with clinicians at least once a month to maintain treatment. If a continuation ECT patient missed an appointment, the ECT staff attempted to contact and reengage the patient. Such active efforts to ensure compliance were probably less vigorous for patients in the antidepressant-alone group. As a result, continuation ECT patients may have benefited both from the psychosocial support of additional contacts with treaters and from an increased likelihood that the biological treatment was actually being taken.

In summary, this study demonstrates that, in chronically depressed patients who have responded to an acute course of ECT, continuation ECT in combination with antidepressants is more effective than antidepressants alone in preventing relapse and recurrence. Prospective research currently underway should provide more definitive data about the magnitude and duration of this effect, as well as about relevant prognostic factors

(25). In the meantime, this study supports the continued judicious use of this therapeutic approach in patients who have failed to tolerate or benefit from long-term antidepressant pharmacotherapy.