Method

Subjects were 30 patients (27 inpatients and three outpatients) with diagnoses of schizophrenia spectrum disorder (24 with schizophrenia, five with schizoaffective disorder, and one with psychotic disorder not otherwise specified). After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Comprehensive clinical assessment—including the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

(8), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the Schedule for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)

(9), and the Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

(10)—was completed with at least two authors present (L.A.F. and T.W.M.); consensus ratings were used.

The Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorders

(11) is a semistructured interview and scale that assesses present and past awareness of illness and symptoms. There are general questions and items that assess awareness of specific symptoms, and participants are asked questions based on symptoms endorsed on the SANS and SAPS. Items are rated on a 5-point, Likert-type scale, with 1 indicating full awareness and 5 indicating complete unawareness of a symptom.

In addition, these subjects, along with 13 healthy comparison subjects, completed a neuropsychological examination and a structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study by means of a 1.5 Tesla General Electric (Milwaukee, Wis.) magnet (parameters: spoiled grass sequence, TE=13 msec, TR=38 msec, flip angle=45°, number of excitations=1), which yielded a series of 124 contiguous, 1.5-mm coronal slices. Lobar region volumes (in cubed millimeters) were calculated by means of a standardized semiautomated procedure developed at the University of Iowa; detailed methods, including boundary definitions, have been previously reported

(12).

Results

On the basis of their average scores for awareness of current episode symptoms on the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorders, patients were divided into two groups: those who were aware of their symptoms (average score ≤3, N=12) and those who were unaware of their symptoms (average score >3, N=18). Groups did not differ in terms of age (aware patients: mean=36.4 years, SD=14.9; unaware patients: mean=33.9 years, SD=9.9) (t=0.55, df=28, p=0.59), full-scale IQ (aware patients: mean=96.0, SD=4.6; unaware patients: mean=93.0, SD=14.3) (t=0.55, df=28, p=0.59), gender composition (aware patients: nine men and three women; unaware patients: 13 men and five women) (χ2=0.03, df=1, p=0.87), or handedness (aware patients: 11 right-handed and one left-handed; unaware patients: 16 right-handed and two left-handed) (χ2=0.59, df=1, p=0.80). All left-handed subjects were men. There was a significant group difference for education; the aware patients were more educated than the unaware patients (mean=13.1 years, SD=2.3; mean=11.3 years, SD=2.8, respectively) (t=2.44, df=28, p=0.03). The patient groups were similar on clinical indices, including total SAPS scores (aware patients: mean=9.4, SD=2.9; unaware patients: mean=10.9, SD=2.8) (t=–1.38, df=28, p=0.18), total SANS scores (aware patients: mean=11.7, SD=3.6; unaware patients: mean=9.5, SD=4.1) (t=1.45, df=28, p=0.16), and BPRS scores (aware patients: mean=41.6, SD=12.0; unaware patients: mean=48.5, SD=7.9) (t=–1.90, df=28, p=0.12).

There was no significant correlation between unawareness of symptoms and education (Pearson’s r=–0.20, p=0.29). Pearson correlations indicated no significant correlations between unawareness of symptoms and either SAPS (r=0.02, p=0.90), SANS (r=–0.03, p=0.88), or BPRS (r=0.30, p=0.10) scores.

Thirteen healthy comparison subjects (no history of psychiatric or neurologic illness or injury) did not differ from the patient groups in terms of age (mean=32.8 years, SD=9.2) (t=–0.41, df=41, p=0.68), sex (12 men and one woman) (χ2=1.97, df=1, p=0.16), or handedness (12 right-handed and one left-handed) (<χ2=0.11, df=1, p=0.81), although they had a higher full-scale IQ, with a mean of 108.3 (SD=8.6) (t=3.64, df=41, p=0.0008). The left-handed comparison subject was also male. The comparison group also had slightly more education (mean=14.5 years, SD=1.8) (t=3.49, df=41, p=0.001) than the unaware patient group.

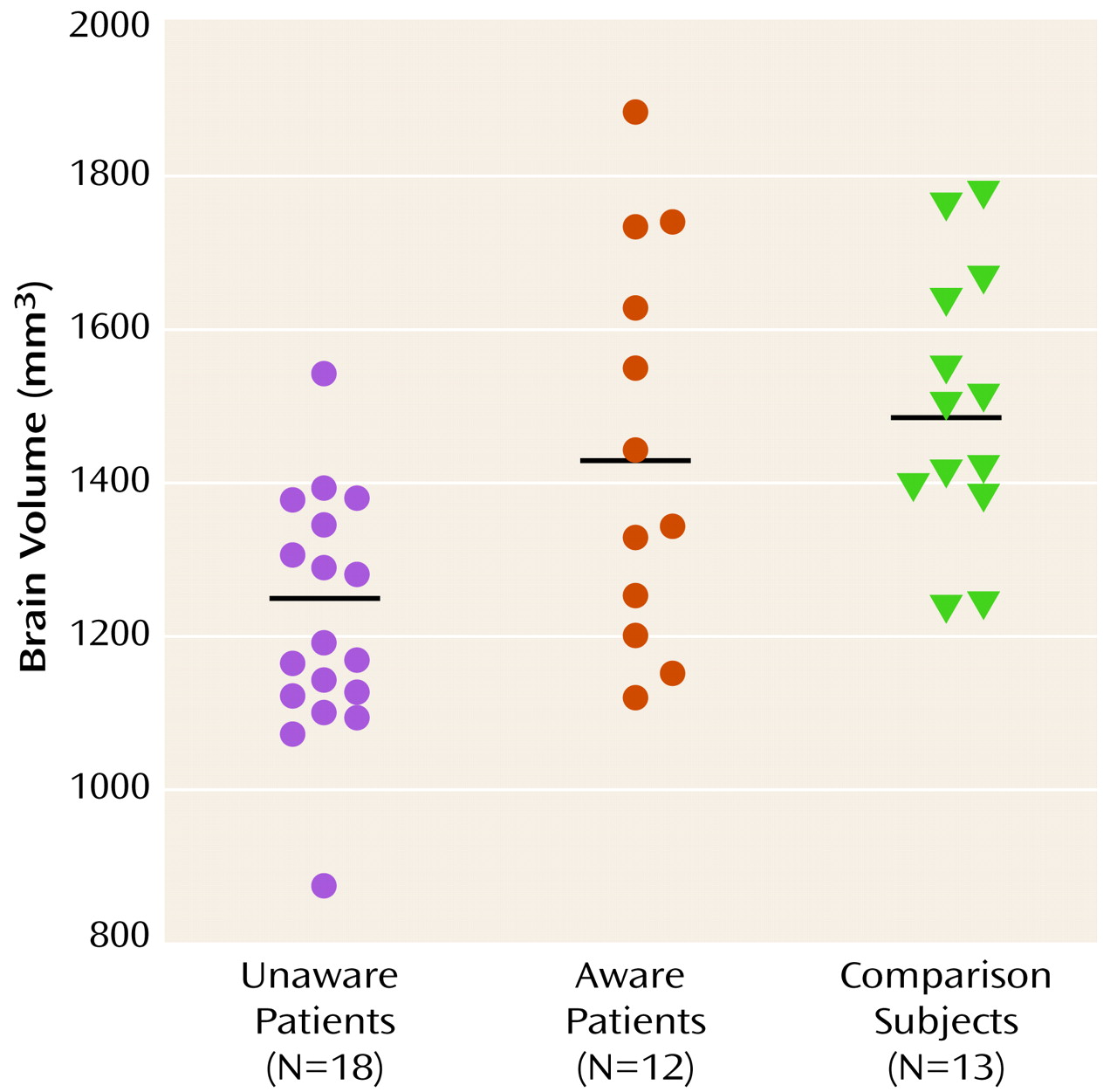

Analyses of variance (PROC GLM, SAS Systems, Inc., Cary, NC) indicated group differences for both brain size (F=9.11, df=2, 40, p=0.0006) and intracranial volume (F=6.50, df=2, 40, p=0.004). Separate planned comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment indicated that the unaware patient group demonstrated smaller brain size (mean=1219.3 mm

3, SD=156.5) and intracranial volume (mean=1426.6 mm

3, SD=188.5) than either the aware patient group (whole brain mean=1441.1 mm

3, SD=255.3; intracranial volume: mean=1672.1 mm

3, SD=293.2) or the normal comparison subjects (whole brain mean=1497.3 mm

3, SD=175.8; intracranial volume: mean=1674.6 mm

3, SD=185.1), although those two groups did not differ significantly from each other. For comparison of individual brain volumes, see

Figure 1. Pearson’s correlations were also used to examine awareness as a continuous variable. Inverse correlations were significant for both brain size (r=–0.47, p=0.009) and intracranial volume (r=–0.44, p=0.02); greater unawareness was associated with smaller volumes.

Finally, differences in lobar volumes were examined for the two patient groups. Although significant lobar differences were noted between the aware and unaware patients groups for bilateral frontal, temporal, and parietal lobe tissue volumes, these differences did not remain significant after intracranial volume was entered as a covariate.

Discussion

Patients with schizophrenia who were unaware of their symptoms were found to have smaller brain size and intracranial volume than patients with schizophrenia who were aware of their symptoms. These differences were found despite nonsignificant differences in gender composition or intellectual ability, which have previously been found to be correlated with brain size

(13,

14). Furthermore, there were no significant relationships found between unawareness of symptoms and positive symptoms, negative symptoms, illness severity, or education. Unawareness of symptoms appears to represent another important dimension of the heterogeneity seen in schizophrenia. Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that unawareness of symptoms represents a distinct phenomenological feature rather than a simple reflection of suffix of psychopathology, symptom severity, or level of cognitive functioning.

We did not find lobar correlates of unawareness of symptoms in schizophrenia, as anticipated on the basis of previous neuropsychological findings. Although our results appear consistent with theories of anosognosia that attribute the deficit to diffuse brain dysfunction

(15), localized involvement cannot be ruled out. An examination of frontal and parietal lobe subregion differences with a larger study group may help clarify this issue.

It will be important for future studies to investigate other correlates of unawareness in schizophrenia. Although there have been a number of investigations examining neuropsychological differences, to our knowledge, this is the only neuroanatomical study of correlates of unawareness of signs and symptoms of schizophrenia. Studies of neurodevelopmental factors, including obstetric complications, genetic and familial risk factors, and functional neuroimaging, would likely provide a comprehensive perspective of the etiology of unawareness in schizophrenia.