Major depression is one the most common and disabling conditions among individuals seeking psychiatric care in general medical and mental health treatment settings

(1). Although the course of the illness in these settings is usually remitting, remission is gradual, and residual symptoms and impairment often persist after remission

(2–

4). Studies of patients in treatment, however, include individuals with more severe illness

(5). Only a small proportion of individuals with major depression in the community seek help in treatment settings

(6,

7). Little is known about the prevalence and course of residual symptoms and impairment among individuals with major depression in the community. This knowledge is essential for assessing the community burden of major depression. A report from the North Carolina site of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study indicated that 38% of the individuals with 6-month major depression had subsyndromal symptoms (minor depression) 1 year later

(8). However, that study did not examine the level of residual symptoms and impairment relative to the time since remission of major depression.

The present study used data from the National Comorbidity Survey

(9), which included a nationally representative household sample of respondents in the United States, to assess the course of residual symptoms and impairment in work functioning and daily activities after resolution of a major depressive episode. With this aim, respondents categorized according to the time since resolution of the last major depressive episode were compared with respondents without a history of major depression. Although a more detailed evaluation of the course of residual symptoms and impairment in the community would require a longitudinal design, the National Comorbidity Survey sample comprises a representative cross-section of individuals in the community at different stages of recovery from a major depressive episode and thus provides a broad but unbiased picture of the course of residual symptoms and impairment associated with major depression in the community.

Method

Sample

As described in more detail by Kessler et al.

(9,

10), the National Comorbidity Survey was a multistage stratified survey of 8,089 individuals between age 15 and 54 years selected from the noninstitutionalized household United States population (48 contiguous states). The survey was administered between September 1990 and March 1992 and had a response rate of 82.4%. Informed consent was obtained before beginning the interviews from all respondents, and, in addition, from the parents of those under age 18 years.

The National Comorbidity Survey interview had two parts. Part 1 was administered to all respondents and included questions about mood and anxiety disorders, including major depression. Part 2 was administered to a subsample of 5,877 respondents (all those identified as having a lifetime disorder in part 1, all those 15–24 years old, and a random subsample of other respondents in part 1). The symptom scale and questions about impairment in the past 30 days were contained in part 2; therefore, the analyses reported in this paper are based on the part-2 sample.

Previous analyses of the National Comorbidity Survey revealed that significant symptoms and impairment were associated with major depression in adolescents and younger adults (ages 15–24), as in the older age groups

(11). Therefore, the 15–24-year age group was included along with other age groups in the analyses reported here. The variable of age, however, was entered into all multivariate analyses to control for its possible effect.

Diagnostic Assessment

The diagnosis of major depression and other disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey was based on a modified version of the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview. The reliability and validity of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview diagnoses of depression and other disorders have been established in previous studies

(12). The instrument was administered by the field staff of the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan. On the basis of information from these interviews, lifetime DSM-III-R diagnoses were generated with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview diagnostic program.

Timing of the Last Major Depressive Episode

Data on the timing of the last major depressive episode were based on two questions: 1) had the period of depressive symptoms ended or was it ongoing? And, 2) if the period had ended, when did it end? In the past month, past 6 months, past year, or more than a year ago? On the basis of the responses to these questions, the following four groups, representing different stages in the course of major depressive episodes, were identified: 1) current major depressive episode group, which included respondents for whom the last episode was ongoing or had ended in the past month; 2) >1 to 6 months group, whose last episode ended within the past 6 months but not in the past month, 3) >6 to 12 months group, whose last episode ended in the past 12 months but not in the past 6 months, and 4) >12 months group, whose last episode ended more than 12 months ago.

Previous studies have found adequate test-retest reliability for self-reported timing of symptoms

(13). It should be noted, however, that the end of the major depressive episode in the present study is not equivalent to “full remission” as defined in DSM-III-R, which requires that no significant signs or symptoms of the disturbance be present for at least 6 months. As would be expected, the proportion of the major depressive episodes that are classifiable as current or in remission and the time since remission of an episode vary with different definitions of remission

(14,

15). The substantive findings of the present study, however, do not depend on any specific definition of the end of an episode.

Symptoms Questionnaire

Specific depressive symptoms as well as nonspecific symptoms of distress were assessed by using 14 questions, mostly drawn from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist

(16,

17). The items covered specific symptoms of depression such as depressed mood, loss of interest, hopelessness, trouble concentrating, inappropriate guilt or feelings of worthlessness, lack of energy, and nonspecific symptoms of distress. The respondents were asked to rate the frequency of each symptom over the past 30 days on a scale ranging from “never” to “often.” For the purpose of this study, these ratings were given values ranging from 0 to 3, respectively. The possible scores on this scale, therefore, ranged from 0 to 42.

The internal consistency of this symptom scale was quite high (Cronbach’s alpha=0.92), and the items were moderately correlated (average interitem correlation=0.45). Principal components analysis of the items produced only one component with an eigenvalue of ≥1, indicating that one latent factor underlies all items.

To establish a cutoff point on this scale for identifying individuals with

significant symptoms, a receiver operating characteristic analysis was conducted

(18). The criterion condition for this analysis was current major depressive episode. The results indicated that a cutoff point of 16 on the symptom scale provided the best combination of sensitivity (0.78) and specificity (0.80). Of the respondents with current major depressive episode, 77% scored at or above this cutoff point.

Assessment of Impairment

The National Comorbidity Survey included three similarly structured sets of questions about days of impairment in work or other activities in the past 30 days

(17,

19), corresponding to the following definitions of impairment: 1) lost days: the number of days in which the respondent was “totally unable to work or carry out normal activities,” 2) cutback days: the number of days in which the respondent had to “cut down” on what he/she did or “did not get as much done as usual,” and 3) difficult days: the number of days in which it took the respondent “an extreme effort” to perform up to his/her “usual level.”

Two questions were asked for each definition of impairment. The first asked the respondent to estimate the number of days within the past 30 days in which he/she experienced impairment. The second asked the respondent to estimate the number of days of impairment that was due to “emotions, nerves, mental health or use of alcohol or drugs.” In this report, the terms “lost days,” “cutback days,” and “difficult days” are used to refer to self-reported impairment days due to emotional and substance use problems.

Data Analysis

Since the aim of the study was to assess the course of residual symptoms and impairment after resolution of a major depressive episode, respondents with a current episode and those whose last episode had resolved >1 to 6 months, >6 to 12 months, or >12 months ago (major depression groups) were compared with respondents without a history of major depression (comparison group). A significant difference in symptoms or impairment between a major depression group and the comparison group would indicate persistent residual symptoms or impairment, respectively, whereas the lack of a significant difference would indicate the return of symptoms or impairment to a level indistinguishable from that in the nondepressed general population. These comparisons would provide a rough indication of the time course of symptoms or impairment after resolution of an episode.

Consistent with this aim, the severity of residual symptoms was analyzed with linear regression in which the major depression groups were dummy-coded and entered as predictor variables. The comparison group was set as the reference category. Current (1-month) generalized anxiety disorder, current dysthymia, the use of any antidepressants during the past year, and age (in multiples of 10 years) were also entered as predictors in the model. The choice of generalized anxiety disorder and dysthymia as predictors was made on the basis of the frequent comorbidity of these disorders with major depression

(10) and the possible overlap of their symptoms with the residual symptoms of major depression. The use of antidepressants was chosen because of the potential impact of treatment on residual symptoms. Unfortunately, the National Comorbidity Survey did not measure the nature or the extent of treatments over the past 30 days. The unstandardized regression coefficients (beta) in the linear regression analysis can be interpreted as the difference in symptom scores between each major depression group and the comparison group, controlling for the effect of other predictors.

Analyses of the number of days of impairment were done with Poisson regression analysis, which is the optimal method for analysis of count data

(20). Three Poisson regression analyses were done, one for each type of impairment (i.e., lost days, cutback days, difficult days). The predictors used in the linear regression described earlier were also used in the Poisson regression. When exponentiated, each Poisson regression coefficient is an estimate of the incidence rate ratio, i.e., the ratio of the incidence of impairment days in each major depression group to that in the comparison group.

Poisson regression assumes that the variance of the distribution is equal to its mean. The variances of the distributions of impairment days, however, were larger than the means, indicating “overdispersion.” Therefore, analyses were repeated by using a modification of Poisson regression, i.e., negative binomial regression

(20), which can accommodate data with overdispersion. As the results of these latter analyses were similar to the results of the Poisson regressions, only the results of the Poisson regressions are reported here.

An alpha level of p≤0.05 was adopted for assessing the significance of the tests for regression parameters. Since these analyses involved a total of 32 statistical tests for the parameters, the Bonferroni-corrected

(21) level of statistical significance was calculated as p≤0.0016 (0.05/32).

The regression analyses addressed the question of how long after the resolution of a depressive episode do residual symptoms and impairment resolve. Pairwise comparisons with Wald tests

(22) were done to assess when the major changes in symptoms and impairment occurred. In these analyses, each major depression group was compared with a temporally adjacent group (i.e., the current major depressive episode group with the >1 to 6 months group, the >1 to 6 months group with the >6 to 12 months group, etc.).

To take account of the complex multistage sampling design of the National Comorbidity Survey, the survey researchers weighted the data to adjust for differential probabilities of selection, differential nonresponse, and discrepancies between the final sample and the total U.S. population on a variety of sociodemographic variables. These weights were used to adjust the descriptive data and the statistical tests reported here. The design-adjusted analyses were conducted by using the Taylor series linearization method

(23), as implemented in the svytab, svyreg, svypois, and svytest routines of STATA 6 for Windows

(24).

Results

Characteristics of the Major Depression Groups

Overall, 995 (17%) of the 5,877 respondents in part 2 of the National Comorbidity Survey met the criteria for lifetime DSM-III-R major depression. Of these, 271 (27%) were in the current major depressive episode group, 206 (21%) in the >1 to 6 months group, 112 (11%) in the >6 to 12 months group, and 406 (41%) in the >12 months group. Respondents whose last episode had resolved a longer time ago, especially respondents whose last episode had ended >12 months ago, tended to be older. The average age was 36.7 years (SE=0.4) in the >12 months group, 33.4 (SE=1.1) in the >6 to 12 months group, 31.1 (SE=0.8) in the >1 to 6 months group, and 31.5 (SE=0.7) in the current major depressive episode group (F=23.6, df=3, 40, p<0.001). As would be expected, respondents with current major depressive episode had more frequent episodes (F=16.5, df=3, 40, p<0.001). For example, 47.3% of respondents with current major depressive episode, compared to 15.3% of the >12 months group, had more than five lifetime episodes. The frequencies of lifetime episodes for the other two groups were between these extremes. There were also minor differences between the four depression groups in age at onset of the illness (F=3.1, df=3, 40, p=0.04). The average age at onset was 22.6 years (SE=0.8) in the current major depressive episode group, 22.7 (SE=0.7) in the >1 to 6 months group, 24.0 (SE=1.1) in the >6 to 12 months group, and 24.5 (SE=0.5) in the >12 months group. There were no differences in gender distribution across the major depression groups. Overall, 65% of the respondents with lifetime major depression were female.

Symptoms and Impairment

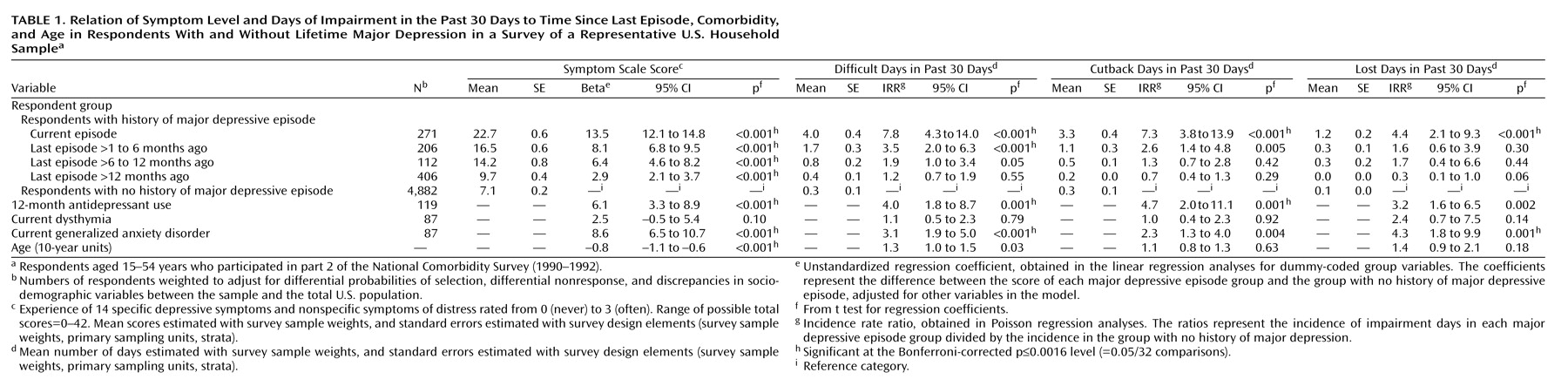

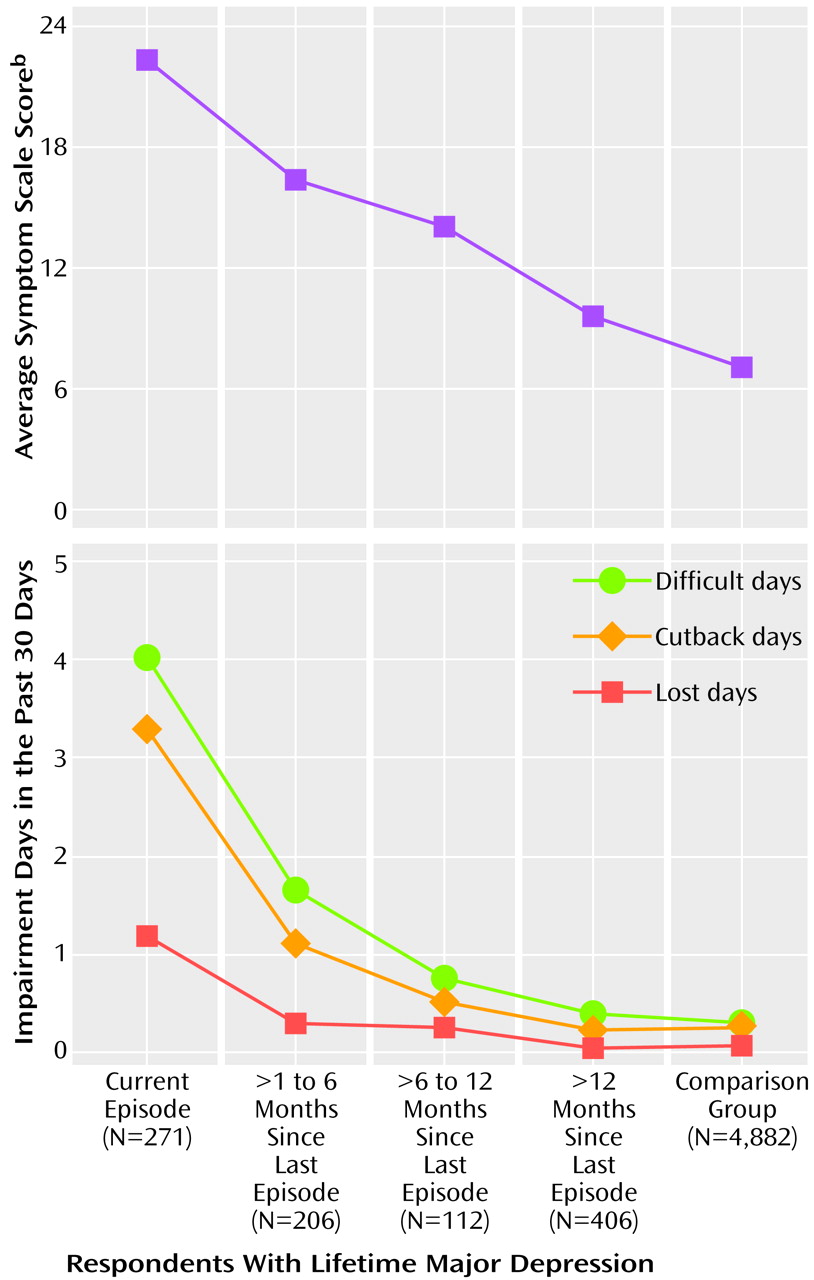

The level of symptoms and number of days of impairment for the four major depression groups and the comparison group are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. As the results of the regression analysis for symptoms in

Table 1 show, the level of symptoms in all four major depression groups was significantly higher than in the comparison group, indicating that residual symptoms persisted more than a year after resolution of the last episode. Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences (p≤0.05) between the current and the >1 to 6 months groups (F=35.6, df=1, 42, p<0.001) and the >6 to 12 months and the >12 months groups (F=14.9, df=1, 42, p<0.001), but no difference between the >1 to 6 months and the >6 to 12 months groups, indicating that the major changes in symptoms occurred immediately after resolution of a major depressive episode and after 12 months. Comparison of the profiles of symptoms across groups did not show that any particular symptoms or group of symptoms were more likely than others to persist after resolution of an episode (data not shown).

Respondents with current generalized anxiety disorder had more residual symptoms, whereas current dysthymia had no impact. The use of antidepressants in the past year was associated with more symptoms. This finding is consistent with other naturalistic studies

(25) and simply indicates that respondents who seek treatment (and receive medication) are more severely ill. Finally, older age was associated with lower levels of residual symptoms. The effect of age, however, was small compared to the effect of the other variables—an age difference of 10 years corresponded to a difference of less than 1 point on the symptom scale.

Among respondents whose last major depressive episode had ended, 52% of those in the >1 to 6 months group, 41% in the >6 to 12 months group, and 23% in the >12 months group scored at or above the cutoff point indicating significant symptoms (a score of ≥16). Overall, a third (34%) of the respondents whose last major depressive episode had ended and 14% of the comparison group scored in this range.

Impairment in work functioning and daily activities followed a different pattern (

Table 1). Only respondents with current major depressive episode and the >1 to 6 months group had a higher number of difficult or cutback days than the comparison group, indicating the resolution of impairment within the first 6 months after the resolution of the major depressive episode. However, the statistical analysis of the number of cutback days for the >1 to 6 months group did not reach the Bonferroni-corrected significance level. Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences (p≤0.05) in the number of difficult days between the current and the >1 to 6 months groups (F=11.3, df=1, 42, p<0.001) and between the >1 to 6 months and the >6 to 12 months groups (F=4.2, df=1, 42, p=0.05). On the number of cutback days, only the pairwise comparison between the current and the >1 to 6 months groups was statistically significant (F=21.1, df=1, 42, p<0.001).

In the Poisson regression analysis for the number of lost days (

Table 1), only respondents with a current major depressive episode had a statistically significant higher number of impairment days than the comparison group, indicating that this form of impairment resolves concurrently with the major depressive episode. Pairwise comparisons for lost days revealed significant differences between the current and >1 to 6 months groups (F=4.3, df=1, 42, p=0.05) and between the >6 to 12 months and >12 months groups (F=5.5, df=1, 42, p=0.02), although the last comparison should be viewed with caution because the average number of lost days in the >12 months group was even lower than in the comparison group.

With regard to the effect of other current disorders and treatment on impairment days, a pattern more or less similar to that for symptoms was observed. However, age had no significant effect on lost or cutback days, and the effect of age on difficult days (which did not reach the Bonferroni-corrected level of significance) was an increase in impairment with age.

Discussion

There were two main findings in this study. First, residual symptoms in major depression tend to persist long after the episodes of the illness resolve. Even respondents whose last major depressive episode had ended more than a year ago were still more symptomatic than respondents without a history of major depression. Furthermore, a third of the respondents whose last major depressive episode had ended had symptom scores indicating significant psychopathology.

This finding has implications for assessment of treatment needs in the community. Point prevalence estimates of major depression that are based on the number of individuals currently experiencing an episode might underestimate the morbidity associated with a lifetime diagnosis of major depression and the need for continued treatment. Treatment of residual symptoms is not only important for reducing current suffering but may also have a preventive effect by reducing the risk of future major depressive episodes

(26).

The second finding is the difference in the course of residual symptoms and impairment. Although symptoms appeared to last indefinitely after resolution of the major depressive episode, impairment resolved shortly after the last major depressive episode ended. The difference in the speed of the resolution of symptoms and impairment was especially pronounced for lost days of work and other activities, which is an indicator of more severe impairment than cutback days or difficult days. Compared with respondents without a history of major depressive episode, only those with a current major depressive episode had a higher number of lost days. The differences in the course of residual symptoms and impairment in this community sample are at odds with findings of studies from treatment settings, which often show that impairment resolves synchronously with symptoms

(27–

29) or even later than symptoms

(30).

One possible explanation for this difference in the course of residual impairment is a difference in the severity of impairment

during the major depressive episode. Subjects in treatment settings typically experience more impairment during their episodes than subjects in the community. For example, Von Korff et al.

(27) found that subjects with major depression in a treatment setting had a mean of approximately 7 days/month of disability (number of days in bed and of days with activity limitation), about twice as much as the mean of 3.7 days/month of disability reported by Broadhead et al.

(8) for depressed subjects in a community setting.

Another possible explanation for the delayed resolution of residual impairment in treatment settings, compared to community settings, may be the severity of symptoms rather than the impairment itself. As Simon et al.

(29) noted, “In more severely depressed patients, improvement in work productivity may not appear until substantial recovery has occurred (a type of threshold effect)” (p. 159). Individuals with major depression in the community may simply be closer to the severity threshold beyond which impairment in work and other activities resolves.

An earlier study of the National Comorbidity Survey sample found that respondents with major depression who reported less severe interference in their daily activities due to the illness were also less likely to seek professional help, be hospitalized, or receive medication for depression

(31). As

Table 1 shows, only 119 (12%) of the 995 respondents with a lifetime history of major depression received antidepressants over the past 12 months. Taken together, these findings suggest that the more limited course of residual work/activity impairment may be a contributing factor to the low rates of help seeking among individuals with major depression in the community, many of whom suffer from residual symptoms and are at risk of future episodes.

In interpreting the findings, however, several limitations of this study and of the National Comorbidity Survey should be considered. First, some evidence from clinical studies suggests that more severe residual symptoms are associated with increased risk of relapse. Thus, subjects with more severe residual symptoms would be expected to relapse earlier and be progressively censored from the sample of respondents at various stages after resolution of the last major depressive episode. Without such selective censoring, the average level of residual symptoms and impairment in these groups would probably be higher.

Second, the categorization of respondents with major depression into four groups was based on somewhat arbitrary and unequal time categories. Thus, whereas the current major depressive episode category included only respondents who experienced an episode within the past month, the >12 months category comprised subjects whose last episode ended from as recently as 13 months ago to as long as several years or even decades ago. More accurate assessment of residual symptoms and impairment would require more refined assessment of timing of the episodes.

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey was funded by NIMH grants MWDA-46376 and MH-49098, a supplement to grant MWDA-46376 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and grant 90135190 from the W. T. Grant Foundation. Ronald Kessler is the principal investigator for the National Comorbidity Survey. Collaborating National Comorbidity Survey sites and investigators are: Addiction Research Foundation (Robin Room); Duke University Medical Center (Dan Blazer, Marvin Swartz); Harvard Medical School (Richard Frank, Ronald Kessler); Johns Hopkins University (James Anthony, William Eaten, Philip Leaf); Max-Planck Institute of Psychiatry Clinical Institute (Hans-Ulrich Wittchen); Medical College of Virginia (Kenneth Kendler); University of Miami (R. Jay Turner); University of Michigan (Lloyd Johnston, Roderick Little); New York University (Patrick Shrout); State University of New York at Stony Brook (Evelyn Bromet); and Washington University School of Medicine (Linda Cottler, Andrew Heath). The author’s work was partly supported by Research Scientist Career Development Award MH-01754 from NIMH and a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression.