Major depression has a 17% lifetime prevalence in the U.S. general population

(1), yet rates of major depression differ among ethnic groups

(1–

6). Suicide is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States

(7), and most suicide victims suffer from major depression around the time of death

(8–

10). Thus, rates of major depression are related to suicide rates

(11,

12). However, estimates of suicide rates in people with affective disorders range from 9% to 60%

(13). Although differences in methods of identifying major depression in suicide victims and differences in access to treatment by different subject groups may contribute to this discrepancy, other factors may be relevant, such as differences between the sexes or among ethnic groups in suicide rates relative to depression rates. We know of no published reports of studies comparing the 1-year prevalence of major depression among whites, blacks, Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ricans in the United States. Furthermore, to our knowledge there have been no studies of suicide rates relative to major depression rates in these ethnic groups. If differences exist, the reasons for the differences may suggest strategies for reducing suicide rates. We decided to determine whether the 1-year prevalence of major depression varies across five major ethnic groups in the United States, whether the suicide rate relative to depression varies among ethnic groups, and whether three sociodemographic factors—disrupted marital status, low income, and not working for pay

(14,

15)—explain the results.

Results

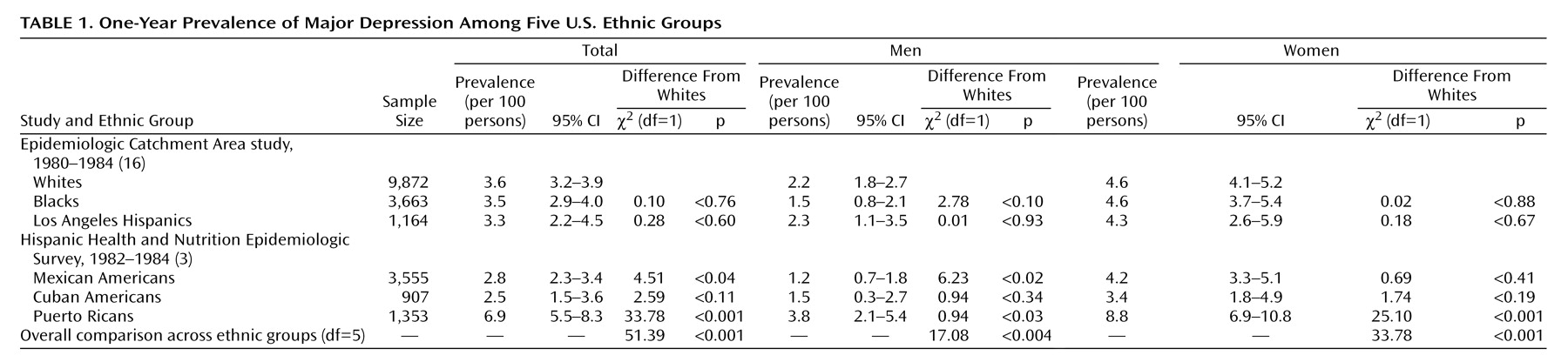

Table 1 shows the 1-year prevalence rates for major depression across the different ethnic groups in the United States. We included the ECA Los Angeles site’s Hispanic group because most of those subjects were Mexican American

(26). This group could thus serve as a comparison group for the Mexican American population studied in the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Epidemiologic Survey, a sample drawn from the Southwest, including California. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for these two populations overlap, with a wider CI for the smaller (Los Angeles) sample. The similar results support comparison of the results of these two surveys. Although the differences in rates of major depression for Mexican American men and Los Angeles Hispanic men in the three groups with specific sociodemographic characteristics (data to be presented later) may indicate that the results of the two surveys are not completely comparable, the CIs for separated and divorced men mostly overlapped, and those for men with low incomes and not working for pay completely overlapped, findings that also support the comparability of the survey results.

The rates of depression among the five ethnic groups were different overall. The 1-year prevalence rate of major depression was lower for Mexican Americans than for whites. In contrast, Puerto Ricans had a higher rate of major depression than did whites.

Among men, the depression rates across ethnic groups were different. Mexican American men had a lower rate of major depression than did whites, whereas Puerto Rican men had a higher rate than whites (

Table 1). Like their male counterparts, Puerto Rican women had a higher rate of depression than did whites in the same gender group. However, Mexican American women did not have a significantly lower rate of depression than white women.

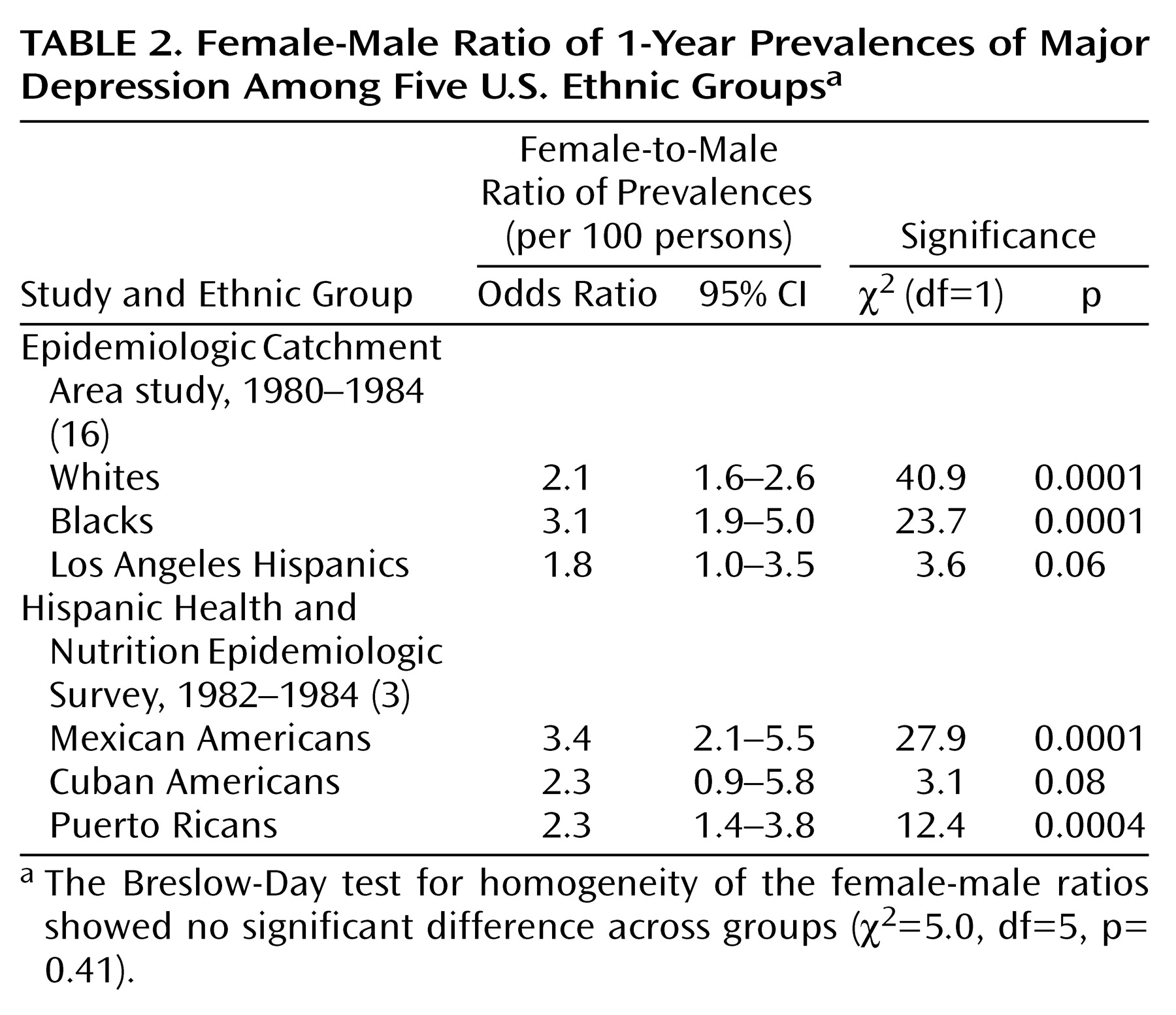

We also compared the depression rates of women and men in the five groups. Consistently, the rates of women were about twice those of men (

Table 2).

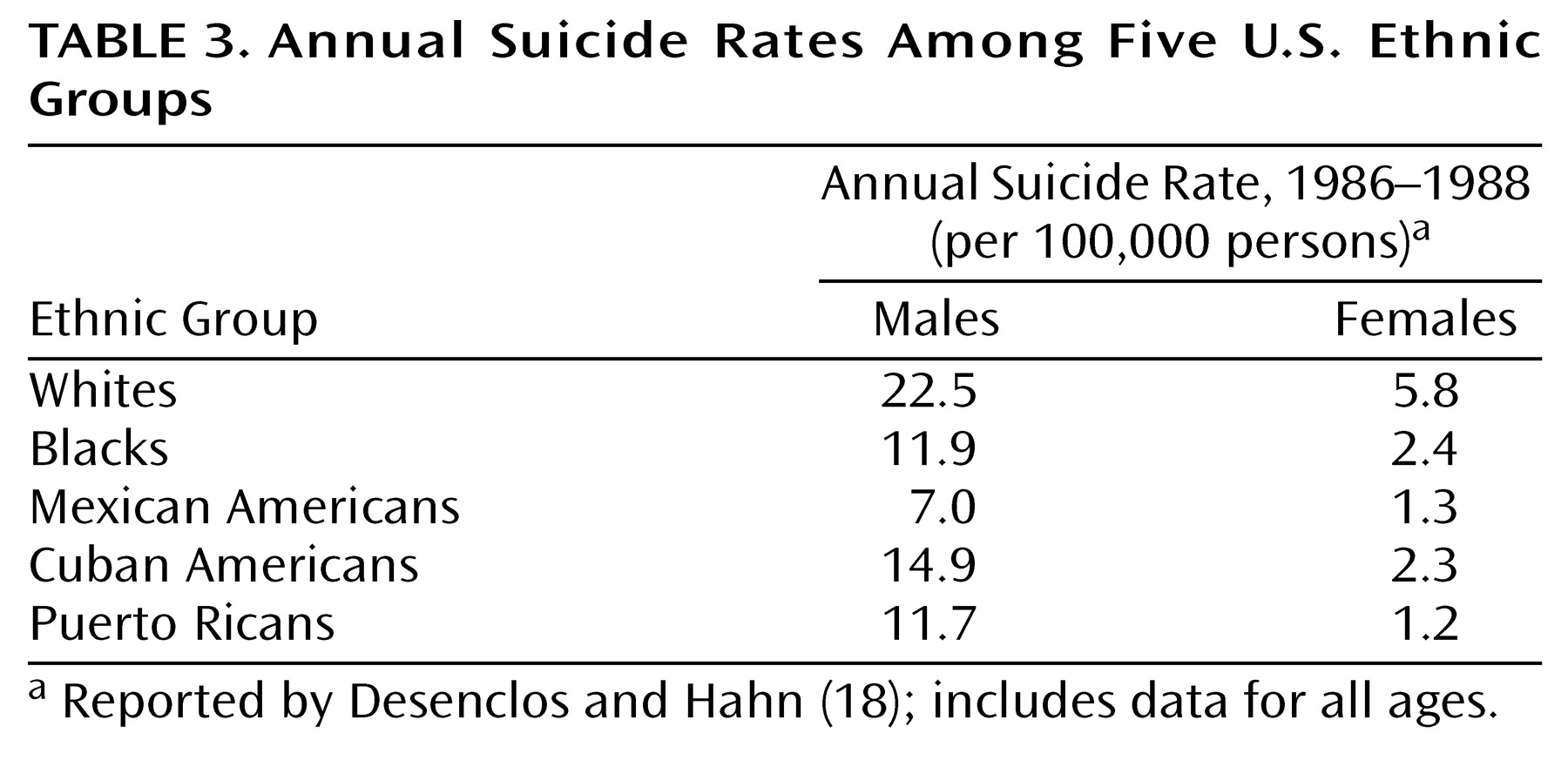

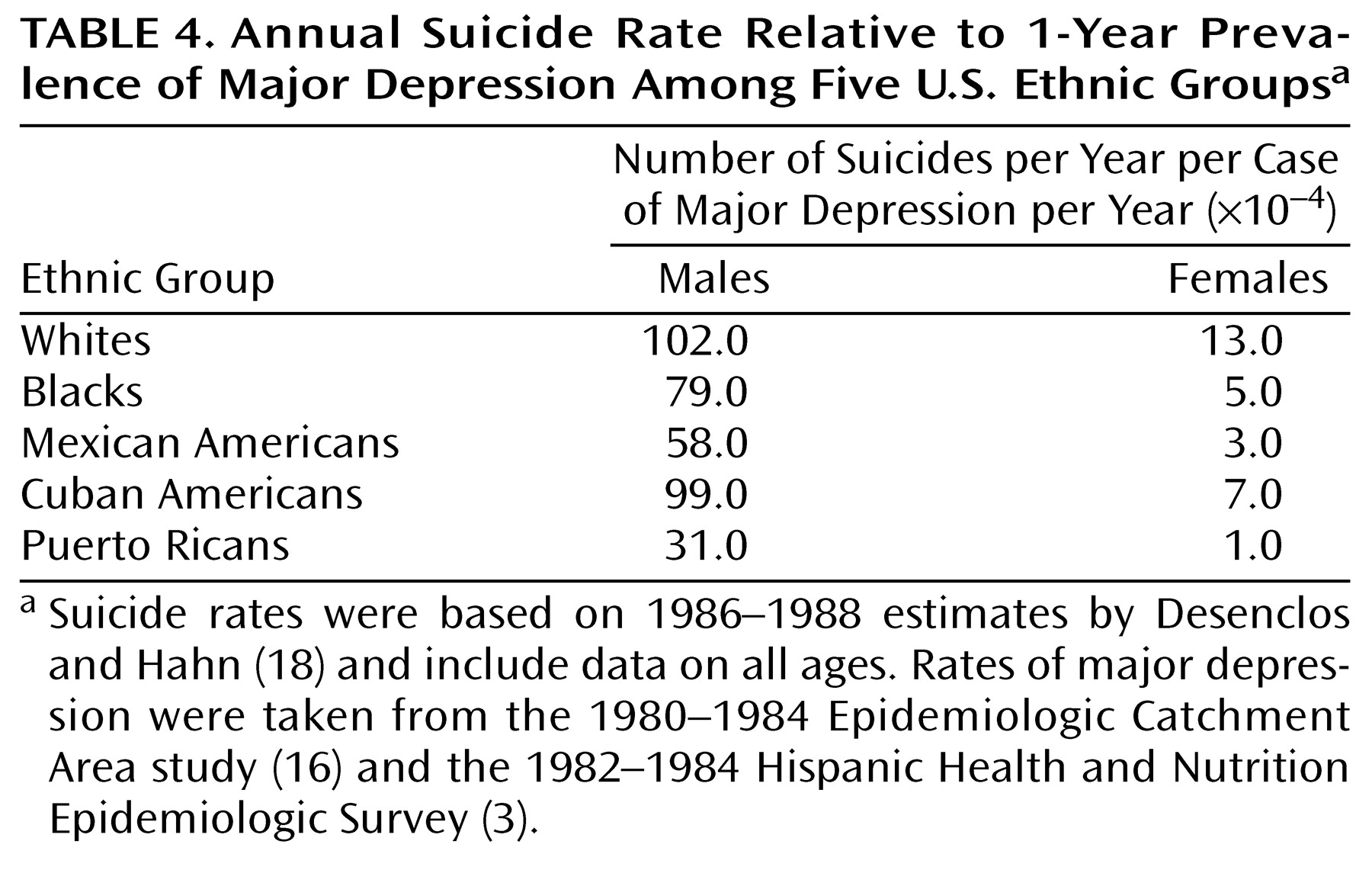

The suicide rates were higher in males than in females among all groups (

Table 3). White males and females had the highest suicide rates relative to depression rates (

Table 4). Mexican American and Puerto Rican males appeared to be better protected from suicide relative to 1-year prevalence of major depression than were the other groups (

Table 4).

Among the females, blacks and Cuban Americans had a relative suicide rate, that is, in relation to the rate of major depression, that was about one-half that of whites. Mexican American and Puerto Rican females had the lowest relative suicide rates, about one-quarter and less than one-tenth that of white females, respectively (

Table 4).

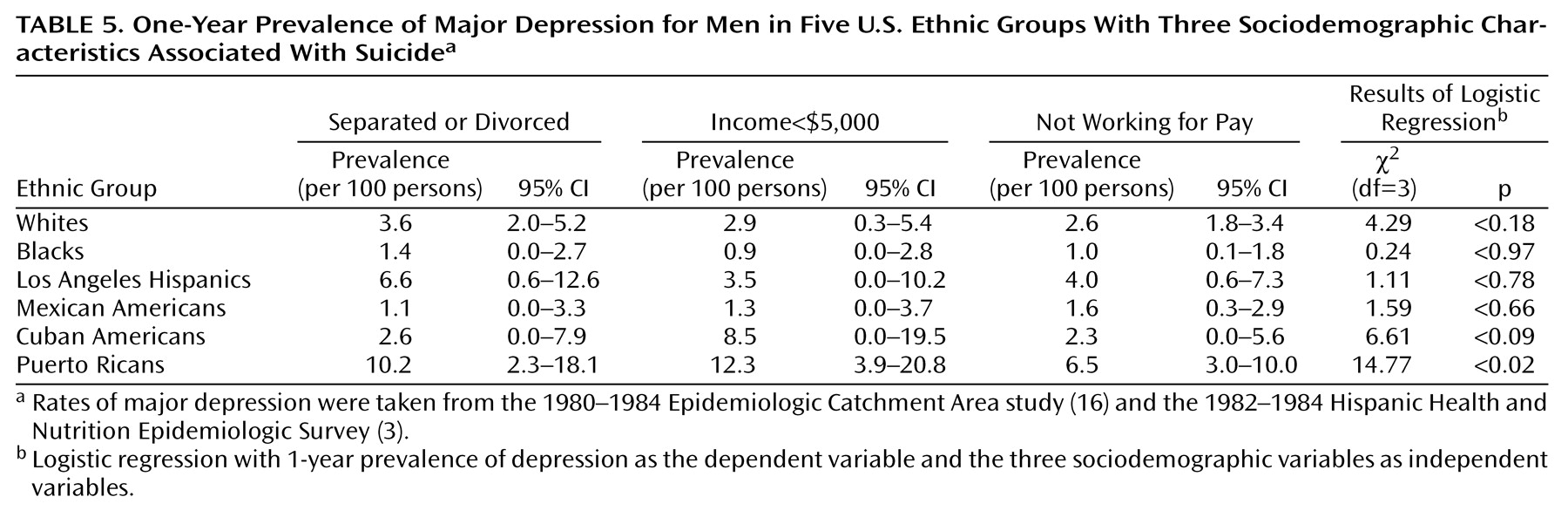

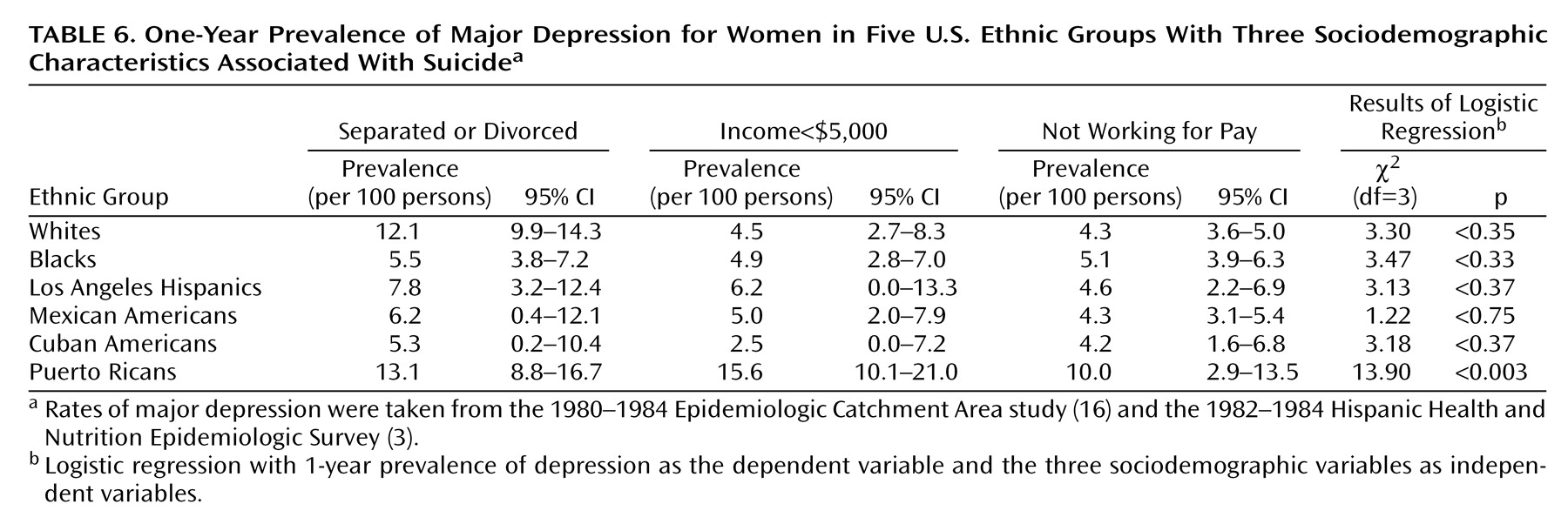

To determine whether the differences in suicide rates relative to the number of cases of major depression were due to variations in the rates of major depression associated with sociodemographic factors, we examined major depression rates for groups with sociodemographic characteristics that may confer risk for suicide (

Table 5 and

Table 6).

Among men (

Table 5), only Puerto Ricans had a significantly higher depression rate, relative to that of white men, if they belonged to the “at risk” sociodemographic group with low incomes (odds ratio=3.99, 95% CI=1.28–12.39, χ

2=5.71, df=1, p<0.02). The rate was not higher for Puerto Rican men with disrupted marital status (odds ratio=2.55, 95% CI=0.68–9.56, χ

2=1.93, df=1, p<0.17) or those not working for pay (odds ratio=0.65, 95% CI=0.21–1.98, χ

2=0.57, df=1, p<0.45).

Puerto Rican women (

Table 6) also were at higher risk for depression, relative to white women, if they were in the group with low income (odds ratio=2.16, 95% CI=1.24–3.77, χ

2=7.40, df=1, p<0.007) but not if they had disrupted marital status (odds ratio=1.42, 95% CI=0.82–2.48, χ

2=1.55, df=1, p<0.22) or were not working for pay (odds ratio=0.84, 95% CI=0.46–1.56, χ

2=0.31, df=1, p<0.58).

In general, the differences in suicide rates (

Table 3) did not parallel the differences in 1-year prevalence rates of major depression among the subjects in the three groups with sociodemographic characteristics associated with suicide risk (

Table 5 and

Table 6). For example, the depression rates among the men in the three sociodemographic groups were not different from the rates for their ethnic groups as a whole, except for Puerto Rican men, who showed a higher depression rate if they had low income. However, the Puerto Rican males had the lowest suicide rate relative to the rate of major depression, suggesting that their higher risk for depression when they are impoverished does not translate to more frequent suicide. The finding was similar among females.

Discussion

We found that the relationship between the 1-year prevalence of major depression and the annual suicide rate varied among five ethnic groups and by gender. Puerto Ricans as a whole and by gender had higher depression rates than whites. Mexican Americans as a whole and men, but not women, had significantly lower rates of depression than whites. Males of all ethnic groups had suicide rates relative to major depression that were an order of magnitude higher than those of the females from the corresponding ethnic group. Among males, whites, Cuban Americans, and blacks had the highest suicide rates relative to the rates of major depression. Puerto Rican males appeared to be relatively protected. Among females, whites had the highest relative suicide rate and Mexican American and Puerto Rican females had the lowest rates.

Prevalence of Depression in Five Ethnic Groups

Although Mexican Americans had a modestly lower 1-year prevalence of depression than whites, Cuban Americans, blacks, and whites had similar, although not identical, rates. In contrast, the 1-year prevalence of major depression for Puerto Ricans in the United States was about double that for whites. Potter et al.

(5) suggested that since the rates of major depression in Puerto Rico have been shown to be the same as in the general U.S. population

(27), perhaps the migratory process selectively involves Puerto Ricans with higher levels of psychological distress. Alternatively, Vera et al.

(28) reported that Puerto Ricans in the New York area, most of whom are impoverished, have the same depression rate as impoverished Puerto Ricans on the island. This is supported by our finding that Puerto Ricans with incomes of less than $5,000 per year had significantly higher depression rates than their counterparts. We also found that Puerto Ricans as a whole had a higher depression rate than whites. It has been suggested that Puerto Ricans in New York have a different response style, leading them to report more symptoms

(29). It is unclear why island Puerto Ricans as a whole would not show this tendency when asked about psychiatric symptoms

(27). Furthermore, that impoverished Puerto Ricans both in New York and in Puerto Rico would show similar rates of major depression

(28) that differ from the rate for the general population of Puerto Rico

(27) suggests that differences in depression rates between New York Puerto Ricans and whites or other Hispanic groups are related to issues other than national origin or identification, possibly socioeconomic.

Relation of Depression and Suicide Rates

Studies from a number of countries have indicated mood disorders in approximately 60% of suicide victims: Finland, 59%

(10); Hungary, 58%

(30); Australia, 55%

(31); England, 70%

(32); Sweden, 59%

(33). These studies have been conducted in largely white populations. However, the apparent stability of the percentage of suicide victims with mood disorders before death is striking, suggesting a close relationship between depression rates and suicide rates. Consideration of ethnicity and gender demonstrates a more complex picture.

The difference in the relationship between suicide rate and 1-year prevalence of major depression among ethnic groups in the United States is remarkable. Possible explanations include comorbid conditions associated with higher suicide rates, such as substance abuse, alcoholism, or borderline personality disorder, cultural and child-rearing environments, adequacy of antidepressant treatment, genetics, and neurobiology. For these groups, there are few data about comorbidity or other factors, such as history of physical abuse, that have significant influences on suicidal behavior in the context of major depression

(14).

We found that Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans of both genders and Cuban American females had lower suicide rates than expected given their depression rates. Black females also seemed to have a lower suicide rate given their depression rate, although the same was not true for black males. The finding that the suicide rate was almost as high for black males as for white males, proportional to their depression rates, was unexpected. Moreover, a study showing a lower suicide rate among blacks did not account for the rate of major depression

(34). Explanations offered included the role of black churches, a bias in reporting, differences in social integration, and differences in emotional expressiveness

(34,

35). Our results suggest that protective factors may be restricted to black females only. Further study is needed to identify these protective factors.

Our finding that, compared to non-Hispanic whites, Puerto Ricans and Mexican Americans of both genders and Cuban American females, but not Cuban American males, have a lower suicide rate relative to the rate of major depression is also unexplained. Cuban Americans, Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, blacks, and non-Hispanic whites are different ethnically. Cuban Americans are more frequently white, whereas Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans tend to be mixed racially, with Puerto Ricans having a significant black contribution and Mexican Americans having a significant indigenous contribution. Moreover, cultural differences among these groups should not be underestimated. The same historical and geographic factors that contribute to differences in racial composition also contribute to cultural heterogeneity. In addition, reasons for immigration differ because of historical and political circumstances. For example, many Cuban Americans have immigrated to the United States for political rather than economic reasons. Differences in suicide rates relative to major depression warrant study so that factors that protect against suicide in major depression may be uncovered.

Reported suicide rates are lower in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Mexico than in the United States

(36). Furthermore, the suicide rate for Hispanics in the United States is almost one-half that for non-Hispanic whites

(18,

37,

38). Although the relationship between suicide rate and major depression has not been addressed in these studies, Hoppe and Martin

(37) offered the concepts of familism and fatalism as contributors to lower suicide rates among Hispanics. Familism, an emphasis on close relationships with extended kinship, may offer protection against stress. Fatalism, the expectation of adversity, may be an adaptive stance in the setting of chronic stress. Both may serve to lower suicide risk in the context of depression.

Relation of Sociodemographic Variables to Depression and Suicide

Variables linked to suicide include unemployment

(15), marital isolation

(14), and socioeconomic status

(14). In our study, the differences in the rates of major depression among members of the five ethnic groups in those socioeconomic categories did not follow the pattern for suicide rates. In fact, the rate of major depression appeared to be influenced by low income only among Puerto Rican men and women. Yet Puerto Ricans were among the most protected from suicide given their high depression rate.

Methodologic Limitations

One of the study’s limitations is that the data about depression come from two surveys. Apart from specific differences in sampling techniques, the ECA study’s main purpose was to assess the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in five sites in the United States, by constructing samples similar to the U.S. population as a whole. The ECA study did not distinguish among Hispanic subgroups. The Hispanic Health and Nutrition Epidemiologic Survey, in contrast, sought information regarding health and nutrition, including but not restricted to psychiatric disorders. This survey targeted three Hispanic subgroups. However, between one-third and one-half of the respondents in the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Epidemiologic Survey did not receive the depression assessment. Alcohol use was the only other psychiatric variable that was assessed systematically. Also, this survey did not cover undocumented immigrants. In addition, both the ECA study and the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Epidemiologic Survey used the DIS administered by lay interviewers, the results of which have been shown to differ from results when clinicians interview the same subjects only a few weeks later

(23).

Also, depression is only one factor leading to suicide. This study did not address substance abuse, schizophrenia, and psychosocial determinants. Also, there are no data with which to investigate factors such as familism or the role of religion in lowering suicide rates relative to depression across ethnic groups.

Another limitation is the assessment of suicide rates. Because only some states in the United States report mortality by Hispanic origin, the suicide rate for each Hispanic subgroup was extrapolated from the rates for states that do report whether or not the decedent was Hispanic. Furthermore, suicide rates may be obscured by accidents or violence. In addition, the suicide rates were from 1986 to 1988. The ECA data were collected between 1980 and 1984, and the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Epidemiologic Survey data were collected between 1982 and 1984. Thus, the 1-year prevalence rates of depression are from 3 to 7 years before the years for which suicide rates are reported. The depression rates for both samples were adjusted to the postcensus estimates for the population for 1987 to address this issue. However, considerations such as the economic environment, which changed over the course of the decade, and its possible differential effects on suicide rates and prevalence of depression could not be addressed. In addition, the suicide rates reported cover ages under 20 and over 74, which are not covered in the reports of depression prevalence.

A further limitation is the use of a general categorization for whites and blacks. Blacks and whites in the United States are of heterogeneous cultural backgrounds and countries of origin. Depression rates that appear similar for Hispanics when taken together, but not when Hispanics are considered as subgroups, might also vary if blacks or whites were to be considered as subgroups categorized by country of origin.

Summary

Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans as a whole, and black and Cuban American females, have lower 1-year suicide rates relative to 1-year prevalence rates of major depression than do whites. Males in all ethnic groups had higher relative suicide rates than females in their respective ethnic groups. The robustness of the finding suggests the presence of as-yet undetermined biological, genetic, or cultural protective factors for suicide. The identification of these factors may guide suicide prevention efforts.