A number of studies in primary care, psychiatric, and substance abuse treatment clinics as well as population-based studies have shown that anxiety and alcohol disorders co-occur

(1–

10). Using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study, Regier and colleagues

(11) found that social and simple phobias have an early onset in adolescence and may predispose to subsequent substance use disorders. On the basis of data from four different geographic sites, Swendsen et al.

(12) reported that phobic conditions (unlike panic or depression) typically precede the onset of alcohol disorders; also, alcoholism, although associated with a higher number of depressive symptoms, was not associated with more phobic symptoms. Magee et al.

(13) also found that social phobia tends to be temporally primary. Furthermore, Kushner and colleagues

(14) found a reciprocal causal relationship between DSM-III anxiety disorders analyzed as a group and alcohol disorders. However, Schuckit and Hesselbrock

(7) concluded in their review that although these disorders co-occur in some studies, the rate of comorbid anxiety and alcohol disorders does not exceed the base rates for these conditions in the general population, and some of the comorbidity may be related to substance-induced anxiety symptoms. Similarly, Allen

(15), in a critical review, stated that anxiety reduction as a factor in the onset of drinking problems is not likely to be a plausible explanation for the co-occurrence of these conditions. He reported that anxiety in many instances is a consequence and not a cause of heavy drinking.

Other studies have examined the familial aggregation of alcoholism and specific anxiety disorders. Merikangas et al.

(16) found that in contrast to the findings for panic disorder, the onset of social phobia tended to precede that of the alcohol disorder and that social phobia and alcoholism tended to aggregate independently. Schuckit et al.

(17) found that the lifetime risk for social phobia among relatives of individuals with alcohol dependence was 2.3%, and they also concluded that there was little evidence for a common genotype for the anxiety and alcohol disorders.

In summary, the relationship of alcohol disorders to individual anxiety disorders may vary. Some studies (e.g., references

11–

13,

16) have produced evidence that the onset of social phobia predates that of the alcohol disorder. There may also be a bidirectional or reciprocal relationship, in that anxiety disorders may lead to alcohol use disorders as well as the reverse (e.g., reference

14). On the other hand, there is evidence

(18,

19) that alcohol consumption does not necessarily reduce anxiety symptoms among people with social phobia. Furthermore, the diagnostic threshold for social phobia may be appreciably altered depending on the level of distress or interference with psychosocial functioning used in the definition

(20).

In this study, we sought to further clarify the role of social phobia as a potential risk factor for heavy drinking and for alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence. Using prospective data from the Baltimore ECA follow-up study (a median follow-up of 12.6 years), we examined whether there was a greater risk for later heavy drinking or alcohol use disorders among individuals with social phobia at the time of the baseline interview in 1981. We separated our social phobia definition so that we could specifically examine individuals who met the full diagnostic criteria for social phobia (DSM-III in 1981) and individuals who reported having an unreasonable fear of specific social situations but not to the degree that they would avoid them or have significant impairment (i.e., subclinical social phobia). We hypothesized that the individuals who had an unreasonable social fear but who did not meet the full criteria for the disorder (in other words, were not attempting to avoid the situation) would be at greatest risk for alcohol use disorders and heavy drinking. Our rationale was that individuals who had an irrational fear to the point that they were functionally impaired and avoided the feared social situations were coping with the anxiety symptoms by using avoidance, thus resorting to less alcohol use. Individuals with unreasonable fears of social situations (such as eating in front of other people, speaking in front of a small group, speaking to strangers, or meeting new people) but who did not avoid these situations would be at greater risk for using alcohol as a potential anxiolytic (whether or not the alcohol consumed was successful in reducing the symptoms). We also specifically assessed risk for alcohol abuse or dependence as well as heavy drinking, believing that individuals with either social phobia condition would be at risk for both heavy drinking episodes and the more severe diagnostic classifications of abuse and dependence.

Method

The ECA Surveys

The ECA program recruited adult participants, aged 18 and older, from 1980 to 1984 at five metropolitan areas, including Baltimore

(21). The ECA collaborators drew probability samples of area residents selected by households and census tracts at each metropolitan site. The baseline sample for the Baltimore site was completed in 1981 (N=3,481; completion rate of 82%). The ECA surveys aimed to measure the prevalence and incidence of specific psychiatric disorders in the general population. In the initial survey, a total of 18,572 household residents were interviewed. All the study data on alcohol use, anxiety disorders, and other psychiatric conditions were gathered with the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) and other standardized interview methods for which reliability and validity estimates have been reported

(21–

24). Neither the interviewers nor the subjects were aware that an association between social phobia and alcohol use disorders or heavy drinking would specifically be tested. The participants gave written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Baltimore ECA Follow-Up

Respondents in the original 1981 cohort of the Baltimore ECA site (N=3,481) were traced and reinterviewed between 1993 and 1996

(25). Of the original respondents, 848 (24.4%) had died in the intervening years. A total of 415 individuals could not be located, and an additional 298 of the original cohort refused to participate in the reinterview. Of the 2,633 survivors, a total of 1,920 (72.9%) were successfully reinterviewed. Prior analyses of the ECA follow-up data have shown that the respondents did not differ from other survivors with respect to age and sex

(26). In addition, individuals who had a history of an alcohol use disorder were not significantly less likely to be successfully traced and reinterviewed than were those without alcohol abuse or dependence

(26). The Baltimore ECA follow-up included a household interview that incorporated the DIS to assess occurrence of substance use and psychiatric disorders, as did the initial baseline interview. The data collection for the Baltimore ECA follow-up continued until 1996. The median length of follow-up was 12.6 years.

Measures

Dependent variables

Case ascertainment for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence was based on computerized diagnoses using data gathered from the DIS, which was based on criteria from DSM-III at the time of the baseline interview in 1981 and on criteria from DSM-III-R during the Baltimore ECA follow-up study. Data on the precision and accuracy of the DIS and further discussion and description of the methods used to define and identify cases have been presented in detail elsewhere

(21–

23,

27).

Heavy drinking was assessed by using a question that was included in both the baseline interview in 1981 and the Baltimore ECA follow-up survey interview: “During the past month, about how many different times did you have five or more drinks?” Individuals who reported having consumed five or more drinks at least once during the past month at the time of the follow-up interview were defined as having an episode of heavy drinking. This definition has been successfully used in other analyses of the ECA survey

(28,

29).

Independent variables

As described in the introduction, in order to test our specific hypotheses, social phobia status was categorized into three mutually exclusive classifications: 1) satisfaction of the full DSM-III criteria (at the time of the baseline 1981 interview) for social phobia, including impairment and avoidance of the feared social situation, 2) an unreasonable fear of a social situation not meeting the criteria for specific avoidance or impairment by this fear (we labeled this condition “subclinical social phobia”), and 3) neither social phobia nor subclinical social phobia (the reference category). In the baseline ECA survey administered in 1981, three specific situations feared by many people with social phobia were assessed: eating in front of other people that the individual knows or in public; speaking in front of a small group of people, such as friends; and speaking to strangers or meeting new people. A current or lifetime history of social phobia and a current or lifetime history of subclinical social phobia were included in the analyses; thus, the two classifications were the two exposure variables. DSM-III criteria were used in this study because that was the current DSM version in use at the time of the baseline ECA survey completed in 1981.

Study sample

Of the 1,920 individuals who were reinterviewed for the Baltimore ECA follow-up, 166 did not complete items on either the baseline or follow-up interview and were excluded from the analyses because the data were not available. An additional 220 individuals were also excluded because their 1981 interviews revealed that they had either current or past alcohol abuse or dependence at baseline and were no longer at risk for these conditions. Furthermore, an additional 373 individuals had episodes of heavy drinking (but did not meet the criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence) at the baseline interview and also were excluded from these analyses. This resulted in 1,161 household residents who were at subsequent risk for the development of alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, or heavy drinking between the baseline and follow-up interviews. These individuals constituted the sample in which we identified the incident cases of the two dependent variables: 1) alcohol abuse or dependence and 2) heavy drinking. We used the term “at risk” to specifically describe individuals who did not have the diagnostic classifications at baseline and therefore were at risk for the future development of them.

Other variables

Potential confounding variables in the analyses that were assessed included age, sex, race, marital status, education level (dichotomized as having or not having a regular high school diploma or general equivalency diploma), age at first intoxication (dichotomized as early or late: before age 15 years or at 15 or later; individuals who said they had never been intoxicated were included in the “late” category), current or prior psychiatric or substance use disorder (affective disorder, anxiety disorder other than social phobia, schizophrenic disorder, illicit drug abuse or dependence). Information for the assessment of these potential confounding variables was gathered from the baseline interview.

Statistical Analyses

In order to assess the presence of potential confounding variables and to evaluate the relative importance of the covariates for inclusion in the multiple logistic regression models, we conducted chi-square analyses of the relationships of 1) the baseline sociodemographic and psychopathologic characteristics with the independent variables (social phobia categories) and 2) the social phobia classifications and the other baseline covariates with the alcohol outcomes (independent variables). After the exploratory analyses, two logistic regression models were used to estimate the degree of association of social phobia and subclinical social phobia with the alcohol conditions. In the first model, referenced to respondents without either social phobia condition, social phobia and subclinical social phobia were assessed for risk of later occurrence of heavy drinking. In the second model, referenced to respondents without either social phobia condition, social phobia and subclinical social phobia were assessed for risk of later occurrence of alcohol abuse or dependence. The logistic regression models provided statistical control of covariates with potential confounding effects.

Results

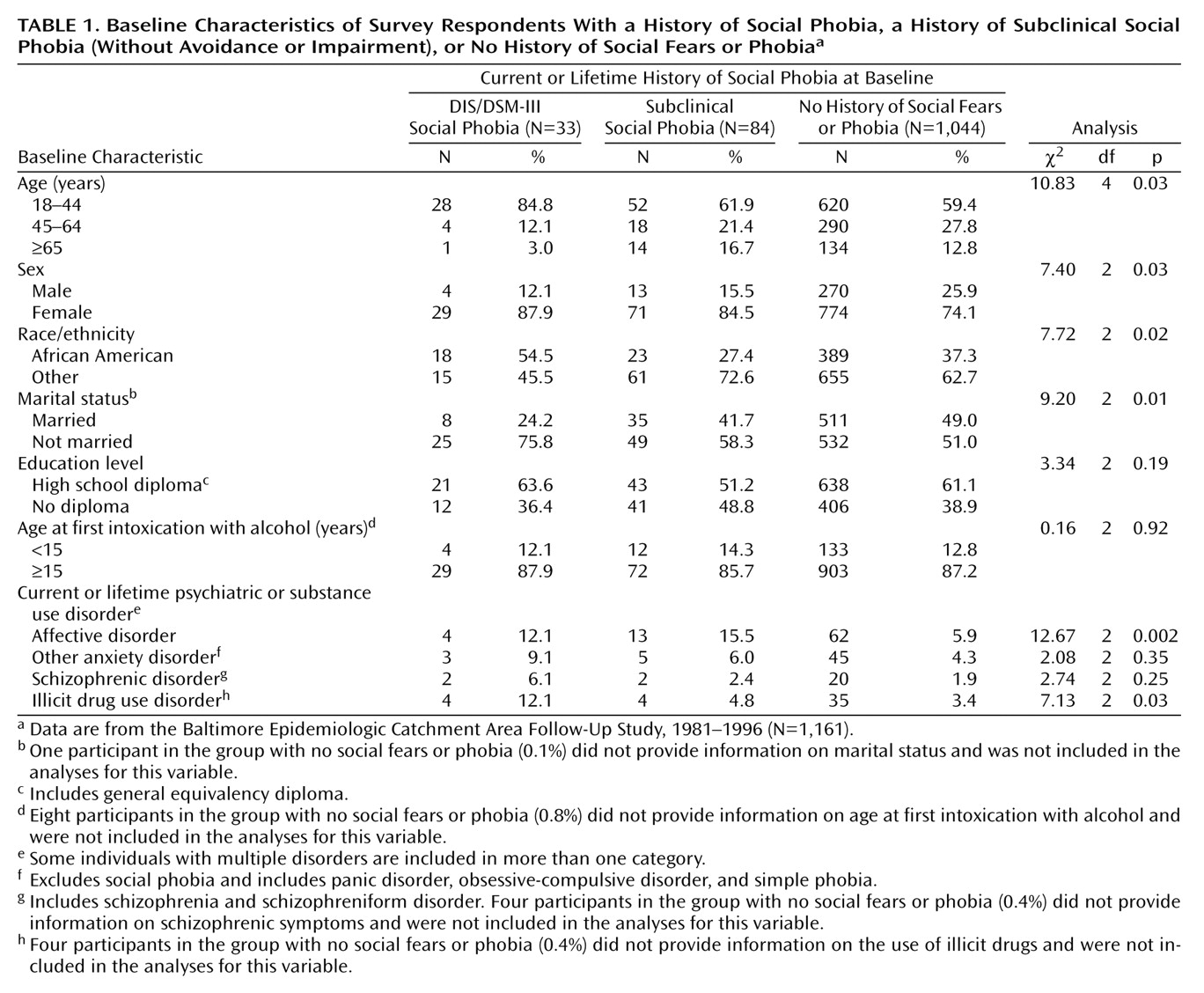

The frequency distribution of characteristics for the individuals with and without a history of social phobia and subclinical social phobia are presented in

Table 1. At the time of the baseline interview, 33 study participants had a history of current or lifetime DIS/DSM-III social phobia, and 84 individuals had a history of social fears without significant avoidance or impairment. The remainder had no history of social phobia or fears (N=1,044). Most of the study participants in 1981 were under age 45. In addition, a significantly greater proportion of those with social phobia were in the youngest age category. Being female, unmarried, and African American were associated with a history of social phobia. Furthermore, a greater proportion of the respondents with a history of social fears or phobia than respondents without them had a history of an affective or illicit drug disorder at the time of the baseline interview. There were no appreciable associations with respect to education level or age at first intoxication with alcohol.

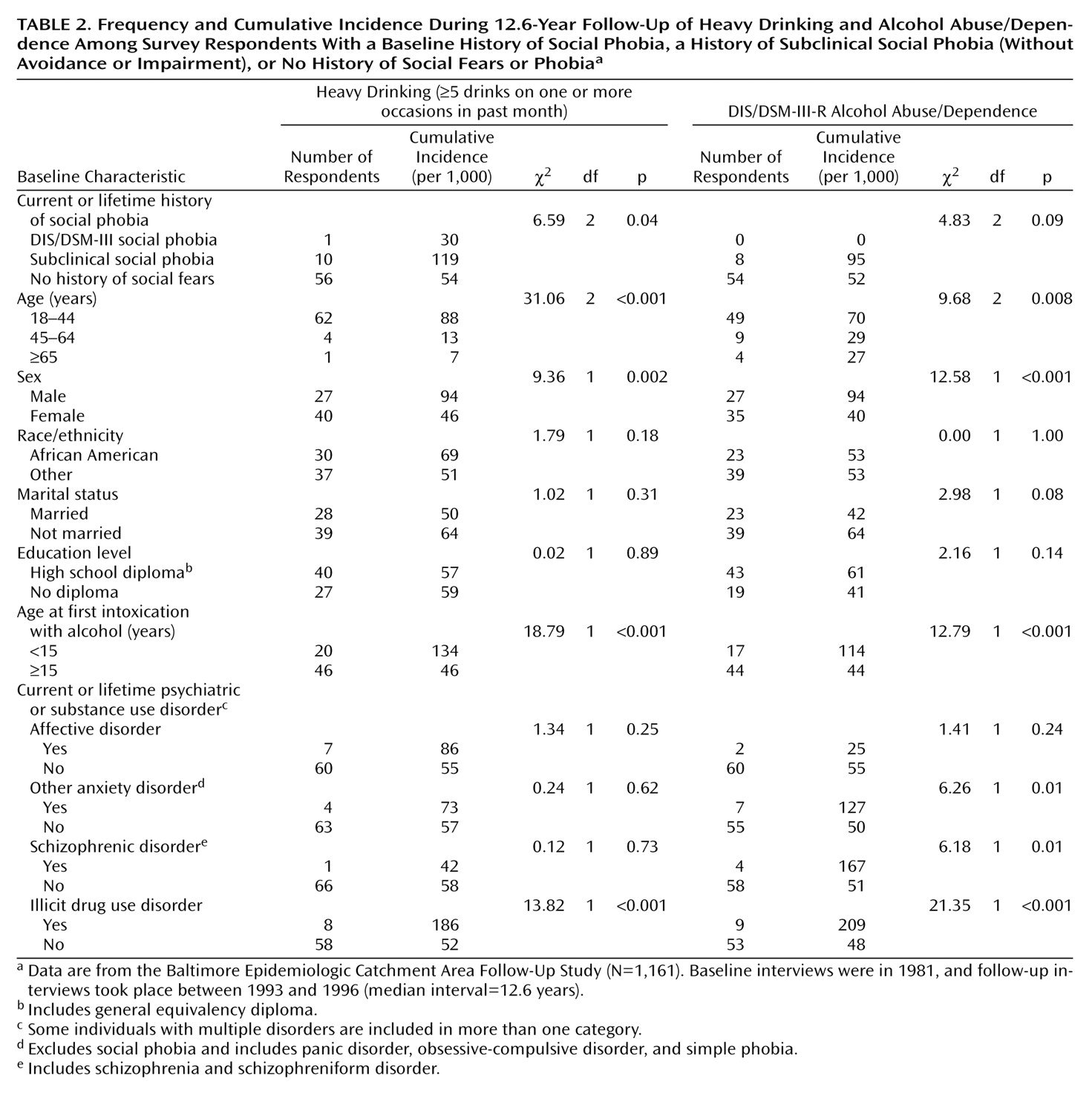

As shown in

Table 2, only one individual with a history of social phobia developed an incident episode of heavy drinking, and none had a new onset of alcohol abuse or dependence at the time of the follow-up interview. There was a relatively high incidence of heavy drinking among those with a history of subclinical social phobia (119 per 1,000), as well as a high incidence of alcohol abuse or dependence (95 per 1,000), when compared to those without a history of social phobia or fears (54 per 1,000 and 52 per 1,000 for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders, respectively). The incidence of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders, as expected on the basis of prior literature, was highest among men, among adults aged 18–44 years, and among those who reported that their age at first intoxication with alcohol was before age 15. The incidence rates of heavy drinking and alcohol abuse or dependence were highest for those with a history of illicit drug use disorder at the time of the baseline interview (186 per 1,000 and 209 per 1,000 for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders, respectively).

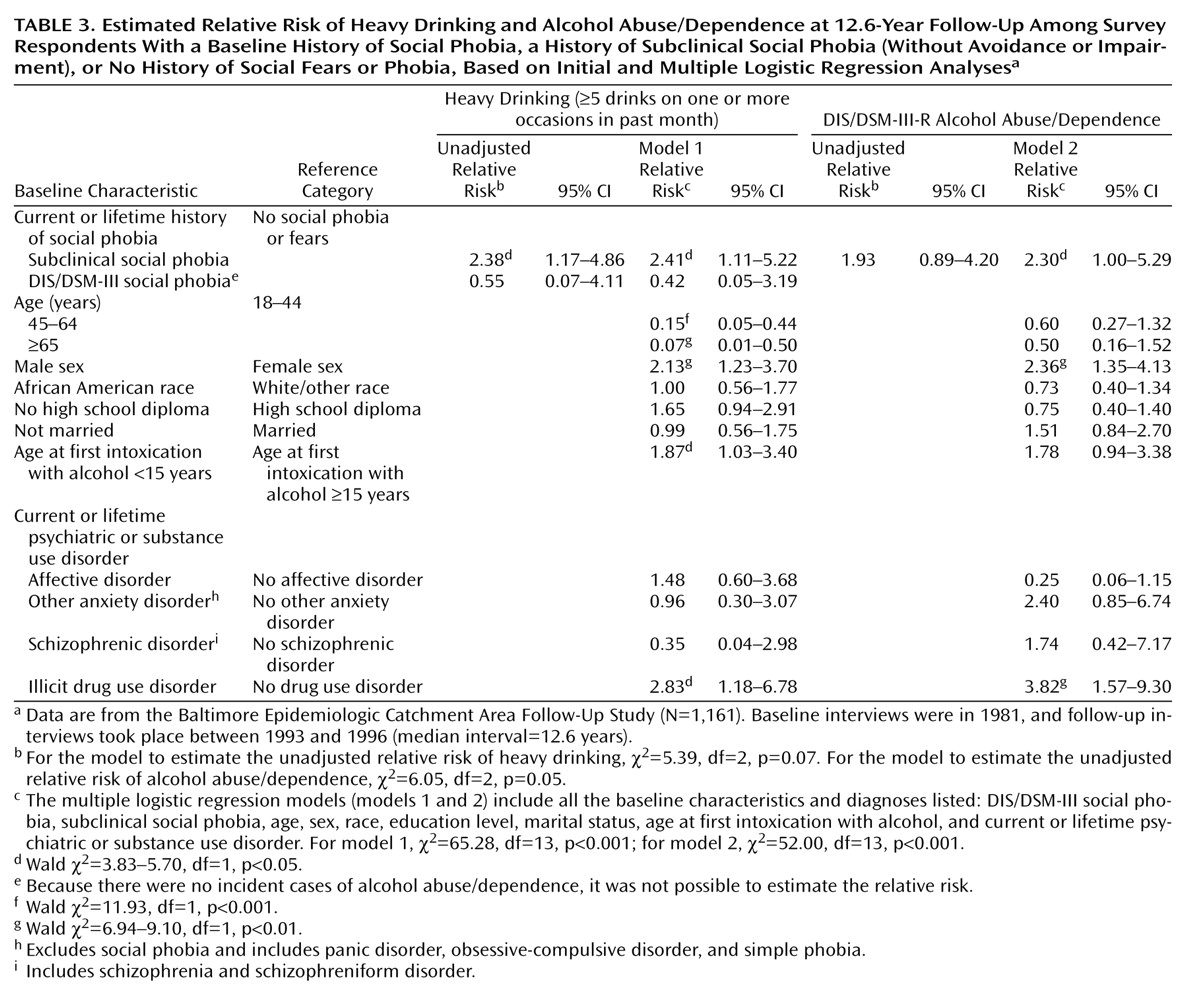

In

Table 3 the estimated relative risks for heavy drinking (model 1) and alcohol abuse or dependence (model 2) by prior occurrence of social phobia and subclinical social phobia are outlined in multiple logistic regression analyses. The crude relative risks did not change appreciably after inclusion of sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, race) and marital status, age at first intoxication with alcohol, and history of other psychiatric or illicit drug use disorders. Individuals with subclinical social phobia were twice as likely to develop heavy drinking and alcohol abuse or dependence as were those without social phobia. On the other hand, a history of DIS/DSM-III social phobia was not associated with a greater risk of heavy drinking, and because there were no incident cases of abuse or dependence in this group, no relative risk was estimated for this outcome.

Discussion

Consistent with our initial hypotheses, subclinical social phobia was associated with high risks of heavy drinking and alcohol abuse or dependence across a median 12.6 years of follow-up. In contrast, there was no appreciable association of social phobia with incidence of heavy drinking or alcohol abuse/dependence. This may indicate that individuals who are not specifically avoiding fearful situations may be at greater risk for using alcohol more frequently and may develop problem drinking behavior over time. The low incidence of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders among those with social phobia may have several explanations. First, the low incidence may be related to the fact that these individuals avoid exposure to anxiety-provoking social situations and may be therefore less likely to self-medicate these conditions with alcohol. Second, individuals with DIS/DSM-III social phobia may also be more likely to enter treatment, and therefore early problem drinking behavior may be identified and appropriate therapy initiated. Third, there is the possibility that individuals with DIS/DSM-III social phobia develop alcohol abuse/dependence or heavy drinking earlier in their lives. As a consequence, these individuals may have had a history of current or lifetime alcohol use disorder or heavy drinking at the time of the baseline interview and would therefore have been removed from our study sample for the assessment of incident alcohol syndromes. However, when we examined the rates of social phobia among participants with and without alcohol disorders or heavy drinking in the baseline sample, we found no significant differences in prevalence. Furthermore, we found no significant differences when we assessed whether those who were excluded from the baseline interview were more likely to have social phobia versus subclinical social phobia. Because of the relatively small numbers of individuals with social phobia who were at risk for alcohol disorders at the time of the baseline interview, firm conclusions regarding this relationship are not possible.

A number of studies have shown that social phobia tends to predate the onset of alcohol problems or maladaptive drinking behavior

(11–

13,

16). Despite growing awareness of its relatively high prevalence

(13,

20,

30–

32) and advances in appropriate identification and treatment

(33–

35), social phobia often goes unrecognized and untreated

(13,

36,

37). The subclinical syndrome is likely to remain unrecognized to a greater degree than the diagnostic disorder, and yet these individuals are potentially at greater risk for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders. It is conceivable that they will not contact psychiatrists or mental health clinics until later in the course of the condition or when comorbid conditions develop. Primary care clinicians may be the first to hear of these irrational fears, and in these clinic settings, knowledge about potential comorbid conditions is important and may improve our understanding of both the etiology of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders and the potential for preventive measures.

Several investigations

(18,

19) have shown that alcohol consumption does not necessarily alleviate anxiety symptoms. It may be the expectation that alcohol will alleviate symptoms that induces drinking. It is possible that the failure of alcohol to substantially alleviate anxiety symptoms does not serve as a deterrent to drinking in a specific anxiety-provoking social situation and that such a failure may actually induce greater drinking because of the person’s hope that at some level of consumption or subsequent intoxication, anxiety symptoms will subside. Although this study does not specifically offer evidence that self-medication is a viable explanation for the relationship between social phobia and risk for heavy drinking or alcohol use disorders, our findings are consistent with this possible explanation.

Several limitations in our study merit discussion. First, because the number of subjects in our social phobia category was small, firm conclusions about these relationships cannot be made. In addition, small subgroups prohibited us from examining alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence as separate outcomes and from more extensively assessing specific findings, such as the higher prevalence rates of the social phobia conditions among African American participants. Second, our study is limited because only three specific situations associated with social phobia were assessed as part of the baseline ECA survey completed in 1981: speaking in front of others, eating in front of others, and meeting new people. Other social fears, such as writing in front of others, were not assessed in this interview. Additional contexts for social phobia will need to be further assessed in longitudinal investigations. Third, because some of the study participants had a history of current or lifetime illicit substance use disorder, we cannot be certain that those with a current drug disorder did not experience social phobia symptoms as a result of their illicit substance use. However, the number with comorbid illicit substance use disorder was relatively small (of the 117 with either social phobia or subclinical social phobia, only eight had a current or lifetime illicit substance use disorder). Fourth, it was not possible to include other risk factors for alcohol use disorders in these analyses because the information was not available. Such potential confounding characteristics include, for example, personality traits and family history of alcohol and/or anxiety conditions. Finally, specific information regarding treatment for phobic or alcohol conditions during the follow-up interval could not be determined.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the study adds to the growing body of literature on social phobia and social fears as potential risk factors for heavy drinking and alcohol abuse or dependence. Although no relationship between social phobia and the incidence of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders was found, individuals with social fears but without significant avoidance or impairment were at increased risk for heavy drinking and for alcohol use disorders during the follow-up interval. Subclinical social fears are potential risk factors for these alcohol conditions and may be appropriate targets for future preventive efforts to reduce maladaptive drinking behavior.