Suicide is the eighth leading cause of death overall in the United States

(1). Many have conceptualized suicide as an inherently aggressive act

(2), and the role of hostility, aggressive behavior, and anger in completed suicide has been emphasized for most of the last century

(3,

4). With the exception of some neurobiological studies

(5), much of the research on the interrelationship of suicide and aggression has focused on personality traits and psychiatric diagnoses related to self-reported hostility and aggression. There remains a paucity of data about overtly violent behavior. In this study, we examined the relationship between violent behavior and suicide.

Research suggests a common neurobiology of suicide and other forms of aggressive behavior

(6). Lower levels of central serotonin distinguish clinical samples of suicide attempters from nonattempters

(7) and are associated with more lethal suicide attempts after psychiatric illness has been controlled for

(8,

9). Longitudinal investigations have demonstrated associations of self-reported aggression

(10) and hostility

(11) with completed suicide.

It is critical to account for alcohol misuse in investigations of the potential role of violence in suicide. For example, alcohol use disorders are strongly related to aggression toward others

(12) and suicide

(13,

14). Therefore, the apparent link between violent behavior and suicide may be spurious, attributable to the high base rate of alcohol use disorders among suicide victims. However, traits related to aggression are associated with attempted suicide

(15–

17) and completed suicide

(18) among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Therefore, it appears that the relationship between aggression and suicide cannot be ascribed to alcohol misuse alone.

The present study tested the hypothesis that violent behavior in the last year of life is associated with completed suicide, even after alcohol use disorders have been controlled for. Given the greater incidence of violent behavior among younger men

(19), we also examined the effects of gender and age on the apparent link between violence and suicide.

Method

Because of their efficiency, retrospective case-control designs are typically employed in studies of rare outcomes or diseases

(20). Suicide, with a base rate of 11.4 per 100,000 per year in the United States

(21), warrants such a design. The case-control approach assumes that variables distinguishing suicide victims from an appropriate comparison group are likely to be risk factors for suicide

(22).

We analyzed data from the 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey

(23). The data were released in 1998 with identifying information expunged to facilitate analyses. The 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey represents a 6-year collaborative project between the National Center for Health Statistics and several federal agencies, state and local governments, colleges and universities, and private associations and organizations. The survey was the sixth in a series first initiated by the National Center for Health Statistics in the early 1960s to provide additional information related to mortality in the United States beyond that obtained through the registration of deaths.

The 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey was based on a sample of 22,957 death certificates from 2,215,000 individuals aged 15 years and older who were residing and died in the United States in 1993. Death certificates were drawn from the 1993 Current Mortality Sample, a 10% systematic sample of death certificates received at the National Center for Health Statistics from state vital statistics offices. For each sampled decedent, sex, age, and cause of death were recorded from the death certificate.

To produce more robust analyses of predictors of death from violent causes, the National Mortality Followback Survey oversampled certain causes of death (e.g., homicide, suicide, accidental injury), certain age groups (e.g., individuals who were less than 35 years old at death) and black decedents

(23). Trained personnel contacted the decedent’s next of kin (or another person familiar with the decedent’s life history) by telephone or in person and asked them to participate in the survey and provide information on the decedent. Informed written consent was obtained before in-person interviews; verbal consent was obtained before telephone interviews. Questions tapped numerous domains, including mental health and health care utilization.

Subjects

We limited the study to individuals between the ages of 20 and 64 because aggression appears to be more closely associated with suicide in younger than older adults

(3). Cause of death was defined by death certificate. Victims of suicide were compared with accident victims. The accidents included motor vehicle accidents (drivers, passengers, motorcycle operators, pedestrians) and poisonings, falls, and other accidents (e.g., drowning or choking).

A total of 3,689 accident victims and 1,363 suicide victims met inclusion criteria. Analyses are based on a subgroup of 2,115 (57%) of the accident victims and 753 (55%) of the suicide victims. Of those included in the analyses, 1,483 (70%) of the accident victims and 517 (69%) of the suicide victims were men; 1,693 (80%) of the accident victims and 653 (87%) of the suicide victims were white, 358 (17%) and 80 (11%), respectively, were black, and 64 (3%) and 20 (3%), respectively, were other minorities. In education, 531 (25%) of the accident victims and 157 (21%) of the suicide victims had less than 12 years of education, 971 (46%) and 329 (44%), respectively, had 12 years, and 613 (29%) and 267 (36%), respectively, had more than 12 years. The remaining accident victims and suicide victims were excluded because of missing data on violence and/or history of alcohol misuse, either because a potential informant could not be contacted, declined to participate, or did not answer one or more of the survey questions regarding these variables. Data were routinely available for demographic variables.

The 653 white suicide victims included in the study represented a higher percentage (57%) of the 1,148 white subjects in the total sample of suicide victims than the 80 black suicide victims (47% of 171) or the 20 suicide victims of other races (45% of 44) (χ2=7.9, df=2, p<0.05). This also held for accident victims: the 1,693 white accident victims represented a higher percentage (59%) of the white subjects in the total sample of accident victims (N=2,878) than the 358 black accident victims (52% of 692) or the 64 accident victims of other races (55% of 116) (χ2=12.5, df=2, p<0.01). The 632 female accident victims included in the study represented a higher percentage of the women in the total sample (61% of 1,030) than the 1,483 men (56% of 2,659) (χ2=9.5, df=1, p<0.01). Likelihood of inclusion in the study did not differ significantly between male (56% of 932) and female (55% of 431) suicide victims. There were no significant age differences in the accident victims or suicide victims that were or were not included in the study.

Measures

Violent behavior in the last year of life was defined dichotomously by response to the question, “During the last year of life, how often did…[the decedent subject] make violent threats or attempts?” Informants were provided with a 4-point scale ranging from often to never. Subjects reported as displaying these behaviors often or sometimes were coded as displaying violent behavior; those reported as displaying these behaviors rarely or never were coded as not displaying violent behavior. The question did not specify the target of violent threats or attempts or if they were directed externally or inwardly. History of alcohol misuse was coded as positive if the informant endorsed one or more items on the CAGE questionnaire, a 4-item screening tool for detecting alcohol use disorders

(24); it was coded as negative if no CAGE items were endorsed.

Statistical Analyses

We used multiple logistic regression to predict case status (suicide victims versus accident victims). A correction for extrabinomial variation was included in each analysis

(25). When this correction is used, statistical significance is tested by using F statistics rather than the usual chi-square statistics. Independent variables of primary interest were violence in the last year, history of alcohol misuse, gender, and age. Race and education were included as covariates, and all variables were entered simultaneously. We tested the main effects for all variables in the model and interactions of violence with alcohol misuse, gender, and age in predicting case status. In addition to performing the overall significance test for multilevel categories, we also examined the parameter estimates and their associated significance tests to help determine the nature of the different effects. All tests were two-tailed, and alpha was set at 0.05. Case weights, provided in the database

(23), were assigned to each case and comparison record to adjust for oversampling and nonresponse.

Results

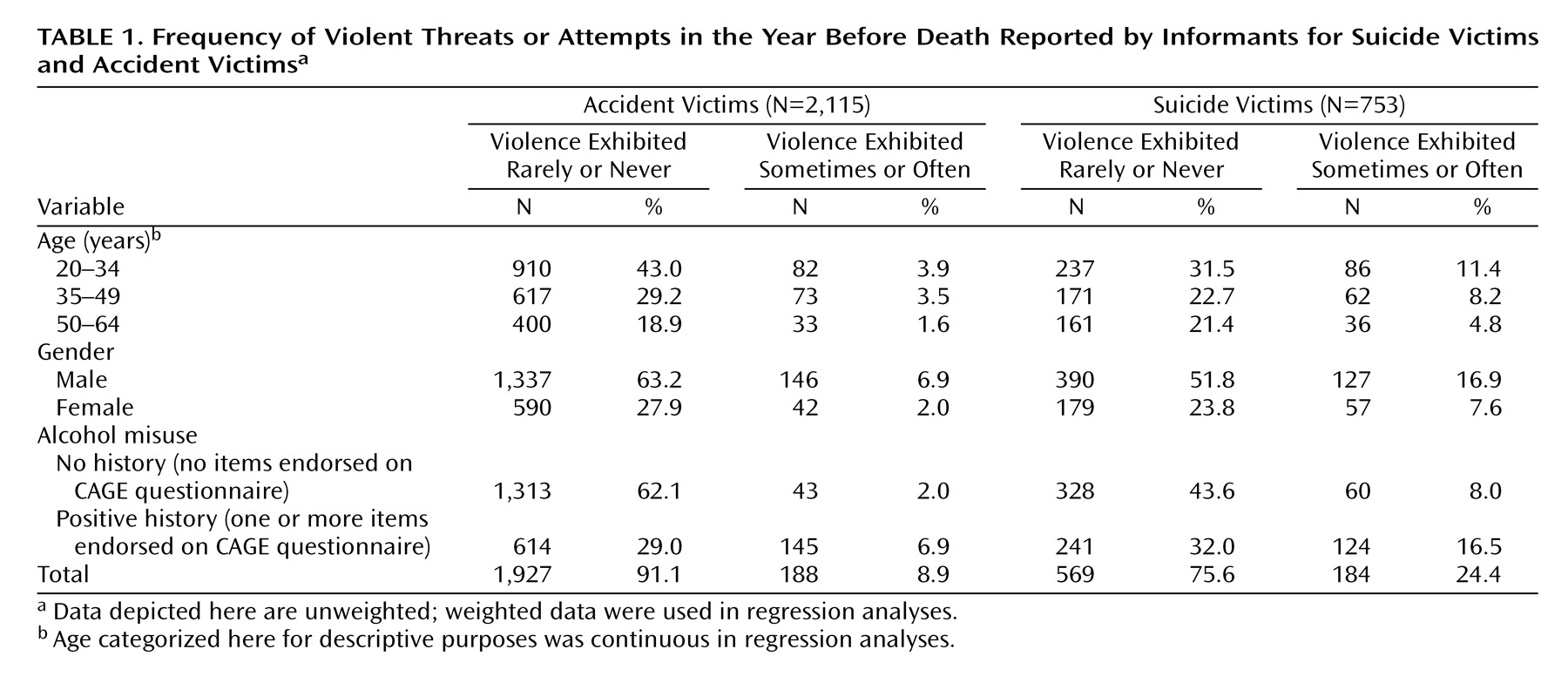

The history of violence in the past year of the suicide and accident victims as well as the variables (gender, age, history of alcohol misuse) investigated for their interaction with violence in predicting suicide are shown in

Table 1. These data are unweighted and thus were not entered in the regression analyses. They are presented in order to provide a concrete indication of the greater level of violence among the suicide victims compared with the accident victims.

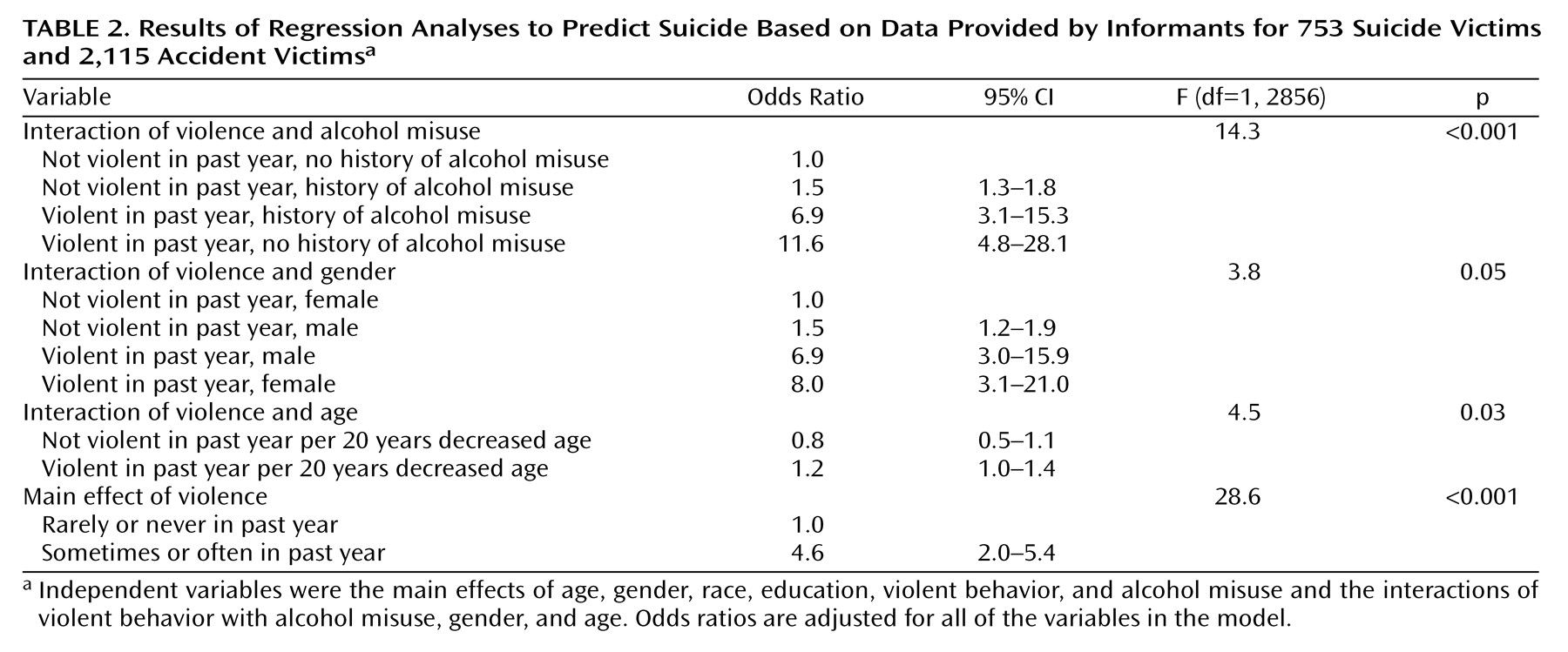

Results of regression analyses are shown in

Table 2. There were significant interactions between violence and alcohol misuse, violence and gender, and violence and age in predicting suicide. The association of violence and suicide was stronger among individuals without a history of alcohol misuse (

Table 1). It was also stronger among women and younger individuals. Suicide risk was also associated with higher education (F=11.7, df=1, 2856, p<0.001), and white race (F=14.9, df=1, 2856, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Even after controlling for alcohol misuse, we found that violence is a potent risk factor for suicide. Given that violence and suicide appear to share many common risk factors

(4), interventions effective in reducing violence may also reduce the potential for suicide. For example, providing behavioral marital therapy to treated alcoholics appears to be effective in decreasing domestic violence

(48). Principal targets of this treatment, alcohol misuse and marital distress and conflict, are also putative risk factors for suicide, and so progress in these areas may also minimize risk for self-harm. Given the apparent risk for suicide among men with histories of domestic violence

(36,

49), family violence courts and mandated domestic violence intervention programs may also be promising settings for suicide prevention initiatives. These efforts are likely to have their greatest impact on relatively younger men. The association between violence and suicide in women suggests that there is a need for novel prevention strategies targeting women displaying aggressive behavior. Overall, violence prevention and suicide prevention initiatives can inform one another and stand to gain by coordination.