Reducing ethnic disparities in access to and quality of health care is a goal of recent federal initiatives

(1–

5). The Surgeon General’s report on minority mental health

(6) emphasized the overall high levels of unmet need for mental health care nationally across diverse subpopulations. While major psychiatric disorders are common across major ethnic groups in the United States

(7–

10), rates of some disorders may differ across groups, e.g., major depression may be less prevalent among African Americans than among non-Hispanic whites

(8).

Among those with similar need, there may be ethnic differences in access to or quality of care for psychiatric disorders. Insured African Americans and Hispanics may be less likely than whites to use outpatient mental health services, while African Americans in the public sector may be more likely than whites to use mental health services

(10–

14). Less acculturated Mexican Americans may have much lower rates of use of mental health care and substance abuse treatment, especially specialty care, than more acculturated groups

(15). Young et al.

(16) found that among U.S. adults with probable depressive or anxiety disorders, African Americans had lower rates of appropriate care than did whites. But prior studies have not compared ethnic groups on multiple domains of access to and quality of care for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health conditions.

In this study we compared adult non-Hispanic whites, African Americans, and Hispanics in access to and quality of care for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health conditions. The study group contained too few data regarding Asian American/Pacific Islanders and Native Americans for separate study. We evaluated care from a consumer perspective, which includes perceptions of unmet need, and from a clinical perspective, which evaluates use of active treatments for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health conditions rather than assessing numbers of visits only. We hypothesized that minorities would have more unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health treatment.

Method

We analyzed data from Healthcare for Communities, a national survey funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Healthcare for Communities survey reinterviewed participants in the Community Tracking Study

(17) about 14 months after their initial interview. The Healthcare for Communities sample was a stratified random sample of 14,985 of the 30,375 adult telephone respondents in the Community Tracking Study; it was oversampled for psychological distress (i.e., shown by those scoring above a cutoff point on a two-item screen of the mental health inventory from the Medical Outcomes Study); use of prior specialty alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health treatment; and family income below $20,000. We obtained 9,585 eligible responses (for a 64% rate of response). Data were weighted for the sampling design and for responses on each survey to represent the noninstitutionalized adult U.S. population. The weighted Healthcare for Communities sample closely matches the 1997 U.S. household population in sociodemographic characteristics

(18). The study design has been described elsewhere

(19).

Independent Variables

We categorized the respondents’ reported main ethnic identification as African American, Hispanic, or non-Hispanic white. Clinical need was assessed for a probable 12-month psychiatric disorder or substance abuse problem. “Psychiatric disorder” was defined as having major depression, dysthymia, or generalized anxiety disorder (as assessed by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Short Form

[20]); probable panic disorder (based on a positive score on the panic stem item on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview plus a positive score for role limitation on the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey

[21]); or probable severe mental illness (as assessed by a positive score on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview stem item for lifetime mania or from a report of ever having had an overnight hospital stay for psychotic symptoms or of having received a diagnosis of schizophrenia from a physician

[22]).

Substance abuse problems were assessed by a positive score for alcohol abuse on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

(23) or recent use of illicit substances as determined from response to items derived from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview

(21). Concordance rates for DSM-III-R diagnoses obtained from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Short Form, and the full Composite International Diagnostic Interview are high, with sensitivity ranging from 77% to 100% and accuracy (specificity) ranging from 93% to 99%

(20). Perceived need was measured by asking individuals if they “needed help for emotional or mental health problems, such as feeling sad, blue, anxious, or nervous” or “needed help for alcohol or drug problems.” Other health assessments were for mental-health-related quality of life, as assessed with the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey

(21), the global mental scale of the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey

(22), and a count of 17 common chronic medical conditions.

We assessed age, family income, gender, marital status, and education and categorized insurance type as uninsured, Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance (fully managed, partially managed, or unmanaged on the basis of extent of use of utilization review, closed provider panels, or gate keeping).

Dependent Variables

Access to outpatient care was measured by self-report of use in the previous 12 months of any mental health specialty outpatient services and any general medical services, including counseling, referral, or other recommendations about a mental health or substance abuse problem. We also measured use of any alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health treatment on the basis of having had an overnight hospital stay, being in day treatment or residential care, and having had an emergency room visit or an outpatient visit for alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health care. Persons with perceived need but no use of alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health care treatment classified as having an unmet need; those reporting delayed care or receiving less care than needed were classified as having delayed care.

For persons with perceived or clinical alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health disorders, we used single-item measures of satisfaction with overall care, care for emotional or mental health problems, and care for substance abuse problems in the previous 12 months. We analyzed data for only the persons responding to each item; many persons who did not make use of such care did not respond to the substance abuse item.

To distinguish active treatment from visits involving assessment only, we developed an indicator revealing use of inpatient, day treatment, or residential care; use of prescribed psychotropic medication daily for a month or more; or a period of potentially therapeutic outpatient treatment for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health conditions, such as four or more outpatient visits or visits to a provider trained in counseling methods, improving skills in relationships or coping with loss, teaching ways to relax, encouraging enjoyable activities or taking responsibility for substance abuse problems, or teaching how to avoid recurrences.

Analyses

We used logistic and linear regression to compare individuals by ethnicity on their demographic characteristics and in access to care, unmet need for care, satisfaction with care, and use of active treatments. Analyses of unmet need were limited to data for respondents with perceived need. Analyses of satisfaction and active treatment were limited to data for persons with perceived or clinical need. To determine whether ethnic differences held after controlling for demographic and health characteristics, we also conducted multiple regression analyses controlling for covariates expected to affect utilization. For each dependent variable, we examined the significance of the overall effect of ethnicity using an F test and looked at differences between whites and African Americans and whites and Hispanics using t tests. To illustrate the results, we generated adjusted (predicted) means and percentages and calculated standard errors using the parameters of the regression models. Some variables (especially income) had missing data, so we used a multiple imputation method for their analysis

(24–

26). All analyses were adjusted for the clustered sampling design by using SUDAAN

(27,

28). For comparisons of whites and minorities in health care use, one-tailed tests seemed appropriate given documentation of disparities among ethnic groups in the literature. The results were in a consistent direction, so formal Bonferroni correction for multiple statistical comparisons was deemed too conservative

(29); instead we considered multiple statistical comparisons in interpreting findings.

Results

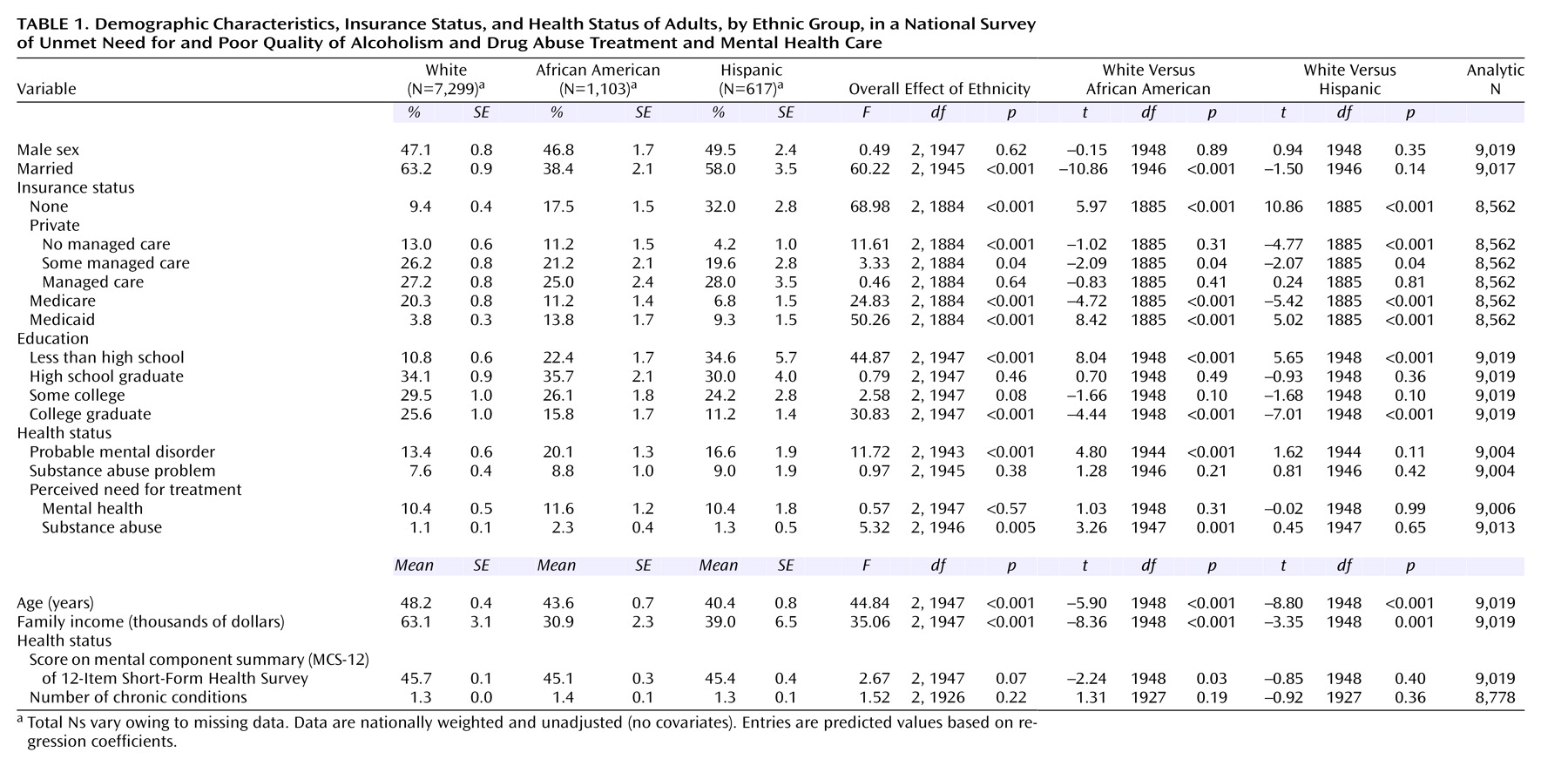

As expected, the ethnic groups differed significantly in demographic characteristics and insurance type (

Table 1). Relative to whites, Hispanics and African Americans had lower mean incomes and less education and were younger and less likely to be married. Hispanics and African Americans were more likely than whites to be uninsured or to be covered by Medicaid, while whites were more likely to be covered under Medicare or unmanaged or partially managed private insurance. Compared to whites, African Americans had higher rates of probable mental disorders (13.4% versus 20.1%, respectively; all data were nationally weighted and unadjusted) and of perceived need for substance abuse treatment (1.1% versus 2.3).

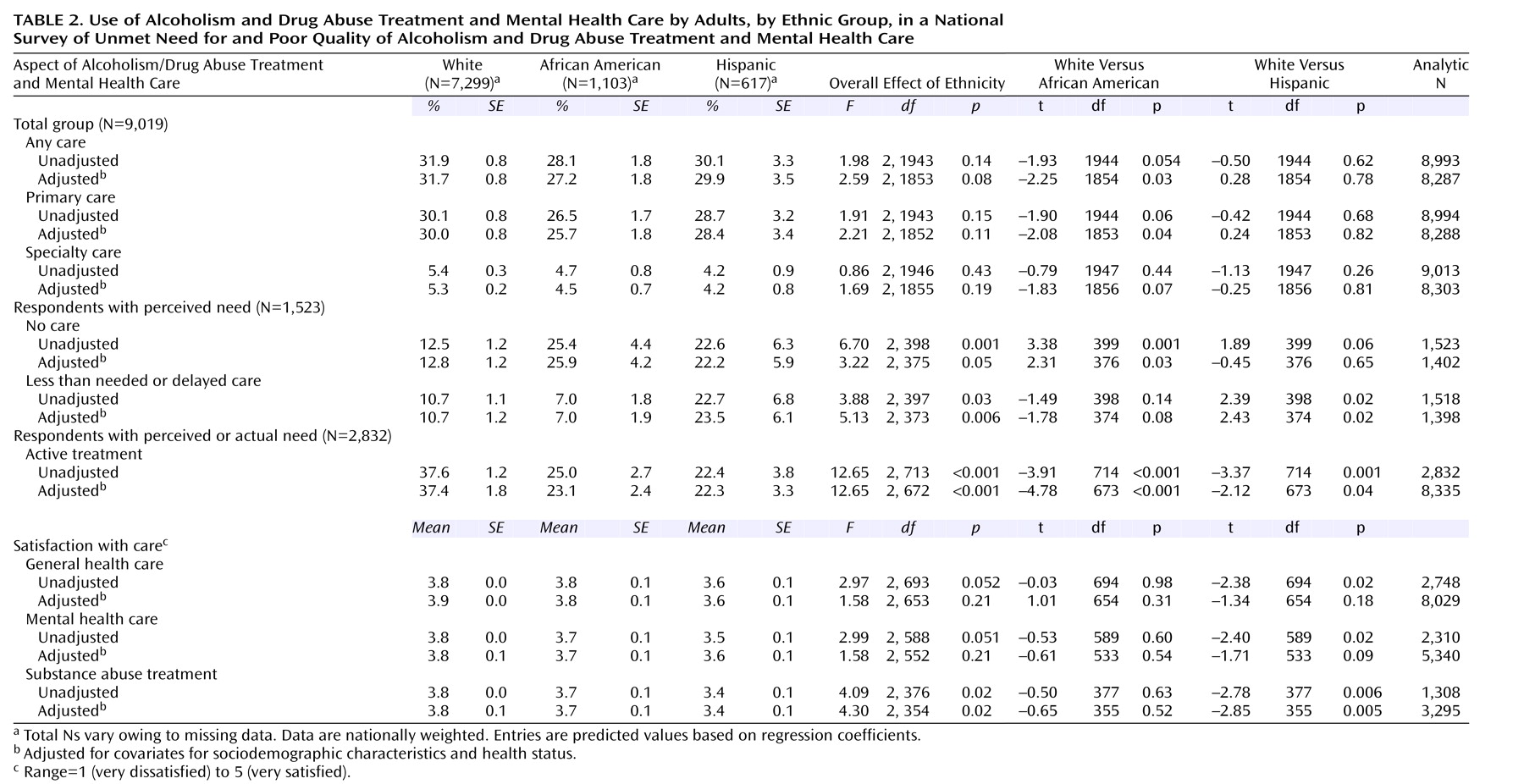

The percentage receiving any alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health treatment was 31.9% for whites, 28.1% for African Americans, and 30.1% for Hispanics (

Table 2). While the overall effect of ethnicity was not significant for any indicator of access, both minority groups had point estimates lower than those of whites for each access indicator, and African Americans had significantly lower use than whites when one-tailed tests were used on adjusted models for any use of alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health treatment; use of primary care alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health treatment; and use of specialty care alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health treatment.

Among those with perceived need for care for alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health disorders, minorities were more likely to report unmet need (12.5% of whites, 25.4% of African Americans, and 22.6% of Hispanics; data were nationally weighted). These differences were significant in unadjusted models, and the difference between African Americans and whites was significant in adjusted models (

Table 2). Furthermore, Hispanics tended to have more delays in care than whites in adjusted and unadjusted models (e.g., 22.7% versus 10.7%).

Among those with perceived or clinical need, whites were more likely to be receiving active treatment (37.6%) than either African Americans (25.0%) or Hispanics (22.4%), and both adjusted and unadjusted comparisons were significant. In addition, Hispanics were less satisfied than whites with every component of health care. These comparisons were significant for all unadjusted models and for satisfaction with mental health and substance abuse care in adjusted models.

Discussion

We found consistent ethnic differences, all in the same direction: less access to care, poor quality of care, and greater unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health treatment for Hispanics and African Americans in comparison to whites. With such consistency, formal correction for multiple statistical comparisons was deemed too conservative, and the overall pattern of findings for each minority group in comparison with whites was considered most relevant. For African Americans, the pattern included less access to care and greater unmet need for care among those with alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental health needs and also a lower rate of active treatment among those in need, relative to whites. For Hispanics, the pattern included more delays in receiving care, lower satisfaction with care, and lower rates of active treatment among those in need. We had somewhat less precision for comparing access for Hispanics versus whites than for African Americans versus whites, but the observed differences in access were relatively small. The ethnic differences in unmet need for care and for quality of care, however, seem large. For example, the percent of those with unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care was twice as high for African Americans as for whites, and the percentage of those in need who were receiving active treatment was nearly 50% less for Hispanics than for whites. Had we applied formal correction for multiple comparisons, differences in unmet need for care and for active treatment would still have been significant. Furthermore, these findings were robust after control for other individual characteristics, including indicators of socioeconomic status.

Our findings complement those of Young et al.

(16), who reported that African Americans have lower rates of guideline concordant care for depressive and anxiety disorders than whites. Our findings suggest, however, that some types of quality-of-care problems extend to Hispanics and involve treatment for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health conditions. Examples of new policies that might address these unmet needs are programs that extend insurance coverage to the near-poor who are in need of care and implementation of quality-improvement programs for major psychiatric disorders in community-based health care settings. For example, effective quality improvement programs have been developed for patients with depressive disorders in primary care settings

(30–

32), but few such programs have been evaluated or implemented for minorities or for those with other psychiatric disorders. Developing programs to improve access to care and quality of care for minorities should be a high priority for psychiatrists, other mental health specialists, and general medical clinicians.

Our study has important limitations, including modest sample sizes of minority groups, an absence of measures of acculturation, reliance on brief screening measures for psychiatric disorders, and use of self-reports regarding utilization. We had only moderate rates of response among persons who previously participated in a national survey, so nonresponse combined across surveys could have biased our results. We applied nationally representative weights to all phases of the study to control for attrition.

Overall, our findings document ethnic disparities in access to care, unmet need for care, and quality of alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care and emphasize the importance of public education and interventions in medical and psychiatric practice to broadly improve the quality of care for ethnic minorities.