Failure of corollary discharge, a mechanism for distinguishing self-generated from externally generated percepts, originally described in the visual system, has been posited to underlie certain positive symptoms of schizophrenia, including auditory hallucinations and delusions of alien control

(1,

2). Self-generated eye movements generate a “corollary discharge,” or “efference copy” of the motor plan, informing the visual cortex that the changing visual input results from a self-generated action

(3). A similar mechanism may exist in the auditory system, whereby corollary discharges from motor speech commands prepare the auditory cortex for self-generated speech, perhaps through a link between frontal lobes, where speech is generated, and temporal lobes, where it is heard

(3,

4). Although typically associated with sensorimotor systems, corollary discharge might also apply to inner speech or thought, which can be regarded as our most complex motor act

(5). Indeed, circuit-based models of brain dysfunction in schizophrenia suggest disrupted connectivity between the frontal and temporal lobes

(6), consistent with the hypothesis of a defective corollary discharge mechanism coordinating auditory responsiveness to self-generated speech (including inner speech) in schizophrenia.

While theoretically compelling, the role of corollary discharge in inner speech, and its failure in schizophrenia, are not easily amenable to direct or even indirect measurement. Recent magnetoencephalography studies

(7) of normal subjects have shown reduced and delayed responses (especially over the left hemisphere) to vowel sounds as subjects spoke them, compared to those sounds when played back through headphones, consistent with suppression by corollary discharge of the responsiveness of the auditory cortex to self-generated speech. Using event-related potentials recorded from healthy subjects and patients with schizophrenia, we directly assessed cortical responsiveness to self-generated speech sounds and to those sounds played back, by using N1, a component generated in the transverse gyri of Heschl of the primary auditory cortex

(8). We predicted that patients with schizophrenia would not exhibit normal reduction of the N1 response to spoken compared to played-back speech, which we expected to observe in healthy comparison subjects.

Method

Seven healthy men and seven men with schizophrenia gave written informed consent to participate in this study after the procedures had been fully explained. The healthy men were screened with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, and their mean age was 35.9 years (range=26–56). The men with schizophrenia were diagnosed according to DSM-IV, and their mean age was 34.1 years (range=23–52 years). All patients were taking atypical antipsychotics at stable doses. They uttered syllables [a:] and [ei] for about 3 minutes, after a demonstration of desired loudness and sequence (interstimulus interval=1.5 seconds, with [a:] on 80% of trials and [ei] on 20%). Each subject’s self-generated vowel sequence was recorded. The subject then listened through headphones to his own sequence of vowels, after first adjusting the playback gain so that the vowels sounded as loud as when he first spoke them. On average, the patients uttered 121 vowels and the comparison subjects uttered 118 vowels.

EEG, sampled every 2 msec, was recorded during both speech production and playback from multiple scalp sites, referenced to linked mastoids. Data recorded from Fza, Fz, Cz, C3, and C4 are presented here. Epochs of 1 second were synchronized to speech onset, corrected for eye blinks, and further screened to exclude speech-related artifacts during speaking, yielding a mean of 69.6 (SD=33.8) artifact-free trials for the comparison subjects and 66.6 (SD=42.5) for the patients. The event-related potentials were collapsed across [a:] and [ei] and were filtered (2–8 Hz) to reduce noise that might affect N1, which was measured as the maximum negativity between 40 and 180 msec.

Analyses of variance for group, condition, and site were performed. Because we attempted a replication of the study by Curio et al.

(7), we used a one-tailed test of significance for condition.

Results

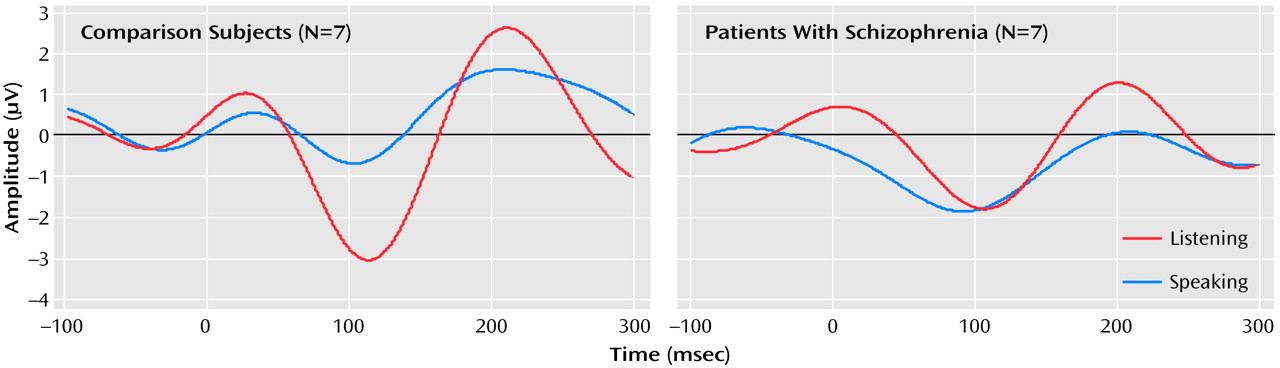

The effects of speaking and listening on N1 amplitude in response to speech sounds differed between the patients and comparison subjects (group-by-condition-by-site interaction: F=5.69, df=2, 24, p<0.02, two-tailed); the group-by-condition interaction was significant for the Cz site (F=4.83, df=1, 12, p<0.05, two-tailed) but not Fza or Fz. This interaction was due to the fact that the N1 elicited by vowels was smaller when the vowels were spoken (mean=–0.96 μV, SD=1.09) than when they were played back (mean=–3.08 μV, SD=2.54) in the comparison subjects (paired t=–2.04, df=6, p=0.04, one-tailed, effect size=0.77) but not in the patients (paired t=0.84, df=6, p=0.22, one-tailed, effect size=0.32 ). In the patients, the N1 during speech (mean=–2.53 μV, SD=2.07) was not smaller than during playback (mean=–2.09 μV, SD=1.64) (

Figure 1. ). Hemispheric effects at the central coronal sites were assessed at C3, Cz, and C4. Although the group-by-condition interaction was significant (F=4.72, df=1, 12, p=0.05), neither the group-by-condition-by-hemisphere interaction (F=0.61, df=1, 12, p=0.52) nor the condition-by-hemisphere interaction (F=2.51, df=1, 12, p=0.12) was significant.

Discussion

The results of this study show that in healthy subjects N1 elicited by uttered speech is less than that while the subject is listening to the speech played back, corroborating previous magnetoencephalography findings

(7) and providing neurophysiological evidence that a speech-related corollary discharge suppresses the responsiveness of the auditory cortex to self-generated speech sounds. Furthermore, that this speech-related N1 reduction was not observed in patients with schizophrenia suggests that this mechanism of auditory cortex suppression is dysfunctional in schizophrenia.

These findings are consistent with those of two other recent studies in our laboratory using acoustic probes to assess cortical responsiveness during speaking and listening to sentences

(9) and directed inner speech

(10). In comparison subjects, but not patients, cortical responsiveness to probes was less during talking than during a silent baseline period

(9). Also, in comparison subjects, but not patients, cortical responsiveness to probes was less during directed silent speech than during a silent baseline period

(10). The N1 response to probes tended to be smaller in patients than comparison subjects during the silent baseline period, perhaps because spontaneous thoughts in patients produce some central acoustic interference, reducing auditory cortical responsiveness.

Our current findings corroborate these findings, extend them to speech utterances themselves, and suggest that speech, whether spoken aloud or generated silently, fails to modulate auditory cortex responsiveness in schizophrenia. We propose that corollary discharge fails to alert the auditory cortex that impending input is self-generated, leading to the misattribution of it to external sources and producing the experience of auditory hallucinations.