From general population studies there is overwhelming evidence of serious undertreatment of individuals with depression

(1). However, since the introduction of the newer antidepressants, antidepressant use has grown markedly worldwide. For example, in Finland antidepressant use increased over fourfold between 1989 and 1998 after the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

(2). Is depression still undertreated?

Only a minority of people with depression seek treatment. In the National Comorbidity Survey only 28% of the respondents with major depression (in 1990 to 1992) reported having used health care services during the previous year because of their symptoms

(3); comparable findings emerged from a telephone interview study in the Toronto metropolitan area in 1996–1997

(4). In two general population studies undertaken between 1988 and 1994, just 7% of young adults with a current major depressive episode

(5) and 18% of subjects with a major depressive episode in the past year

(6) were currently taking antidepressant medication. In the European DEPRES II study

(7), 30% of depressed subjects with health care contact in 1994 were receiving antidepressant treatment. However, both help seeking and provision of treatment may have increased over time. In the present study we investigated the prevalence of antidepressant use among subjects with a major depressive episode in the Finnish general population in 1996.

Method

The present study formed part of the Finnish Health Care Survey, in which subjects in a random population sample of Finns were interviewed face-to-face by professional interviewers in 1996 (8). The sample analyzed comprised 5,993 subjects aged 15–75 years (details of sampling are provided in references

8 and

9). The depression section of the Short Form of the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview

(9,

10), including the DSM-III-R criteria for major depressive episode, was used to assess depression. The overall diagnostic agreement of the short form with the full Composite International Diagnostic Interview for major depressive episode is 93%

(10). The age-adjusted prevalence of depression during the preceding 12 months was 9.3% (N=557)

(9). The interview also included questions concerning the use of health care services and all medication use. All subjects participating in this study gave formal consent.

Age, gender, severity and duration of the major depressive episode, number of chronic conditions, number of medications, duration of sick leave (during 1996, irrespective of diagnosis), marital status, family income, education, employment, type of residential area, alcohol use, and smoking status were the variables chosen for logistic regression models, with antidepressant use as the dependent variable. All these variables were first analyzed alone in logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, and the severity and duration of the major depressive episode. The final multivariate logistic regression model for antidepressant use included all the significant variables (p<0.05) adjusted as just described. The severity of depression was dichotomized according to the number of depressive symptoms included in the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form: lower (3–5 symptoms) versus higher (6–8 symptoms). Age and duration of the major depressive episode were examined as continuous variables, the latter in 3-month intervals. Primary health care services included care provided by health centers and occupational public, private, and other medical services; psychiatric services included public and private services provided by a psychiatrist. SPSS version 9.0 was used for statistical analyses (Chicago, SPSS).

Results

Of the 557 subjects with a major depressive episode during the previous 12 months, 27% (151 of 557) reported that they had used health care services because of their depressive symptoms. Only 11% (61 of 557) had used primary health care services, another 16% (90 of 557) had used psychiatric services. Of the subjects with a major depressive episode, 13% (70 of 557) reported current use of antidepressant medication. Novel antidepressants such as SSRIs and moclobemide were used by 41 subjects, while 38 used other antidepressants, mainly tricyclic antidepressants. Benzodiazepine medication was used by 14% (77 of 557), and 4% (22 of 557) used neuroleptic medication; overall, 23% of the subjects with a major depressive episode (126 of 557) reported any use of psychotropic medication.

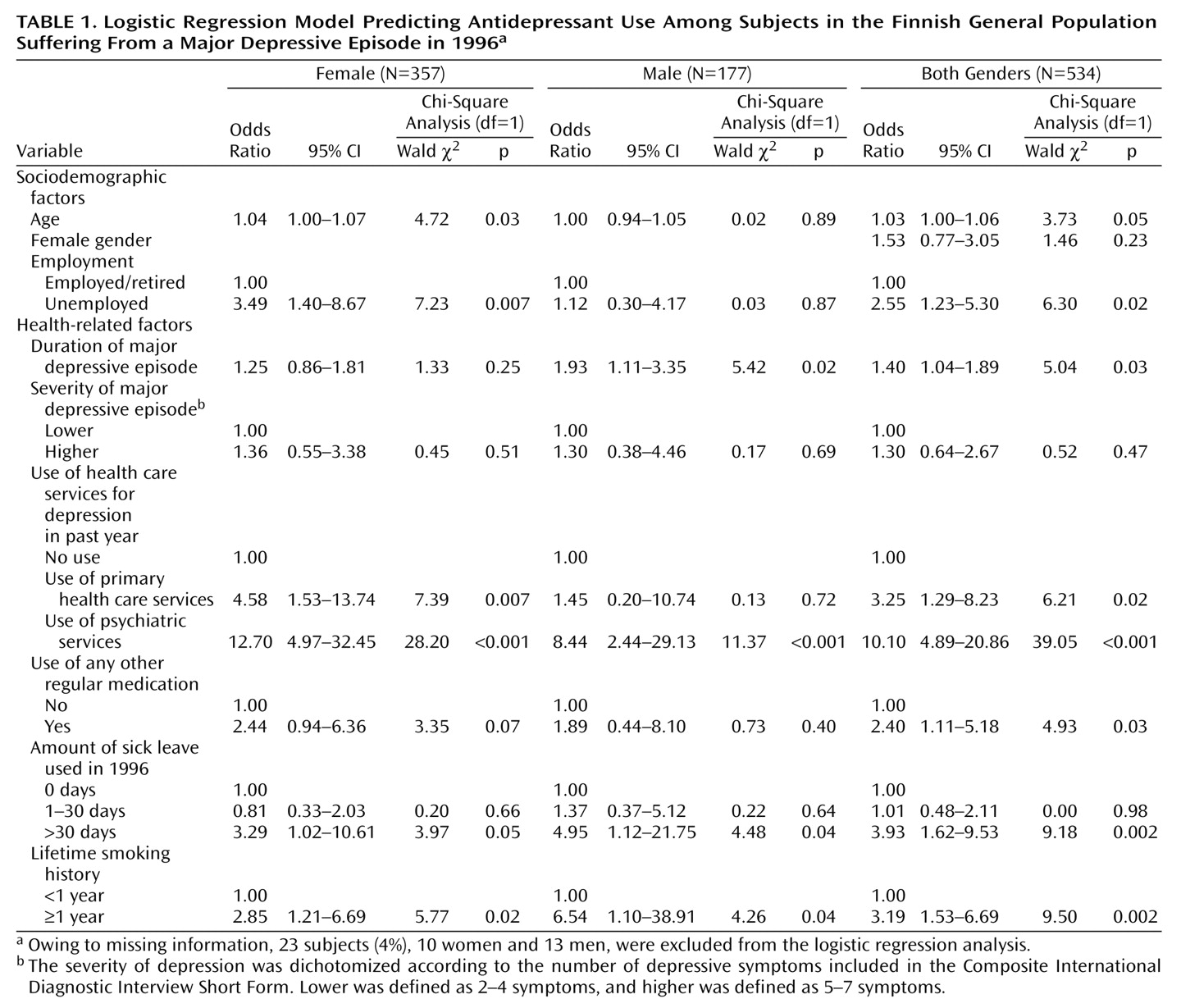

The main predictors of antidepressant use (

Table 1) were the use of psychiatric services for depression, cumulative sick leave of more than 1 month, smoking for more than 1 year, and any other regular use of medication. In gender-specific analyses the duration of the major depressive episode was associated with antidepressant use among men, while older age, the use of primary health care services for depression, and unemployment were associated with antidepressant use among women.

Discussion

We found that in the Finnish general population in 1996, depression was still largely undertreated, despite the several-fold increase in the use of antidepressants during the 1990s. Only 13% of the subjects with a major depressive episode during the previous year currently received antidepressant medication.

We know of no other large-scale general population studies conducted with face-to-face interviews for which there are reports of antidepressant use for depression in the latter half of the 1990s. While this study was based on a large, nationally representative general population sample

(8,

9), used a standardized interview to determine the presence of depression

(9,

10), and carefully evaluated the use of medication, some methodological limitations exist. Information on medications was restricted to current use, while the prevalence of major depressive episodes involved the preceding 12 months. Subjects may thus have used antidepressants and discontinued that treatment before the interview. However, even among subjects with current or very recent major depressive episodes, the prevalence of antidepressant use never exceeded 25%. This limitation is thus unlikely to have undermined the validity of the overall finding of undertreatment, although it may have caused underestimation of antidepressant use. Nonmedical treatments of depression were not investigated. Finally, our findings concern major depressive episode, not strictly defined unipolar major depression.

In studies from the late 1980s and early 1990s

(5–

7) and a recent telephone interview study

(4), 7%–18% of depressed subjects were receiving antidepressant treatment. The present finding from the latter 1990s that only 13% (up to 25% for recently diagnosed subjects) of people with major depressive episodes are using antidepressants suggests that still far too few depressed subjects receive antidepressant treatment.

We found, after controlling for the severity and duration of depression, that the use of psychiatric services because of depression was the strongest predictor of antidepressant treatment. This is consistent with findings from Ontario in 1990–1991

(6). The use of primary health care services was associated with antidepressant treatment only among women. Our findings also suggest that duration of sick leave may be a factor independently related to the use of antidepressants. Overall, our findings indicate that depression is still largely undertreated in the general population, despite the major increase in use of antidepressants in the 1990s.