Subjects were recruited by advertisement and from outpatient services at Stanford University Medical Center, McLean Hospital, and Washington University School of Medicine. Screening included a psychiatric interview, administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)

(7), clinical ratings, and a medical evaluation with a physical examination. Ratings were conducted by staff who had demonstrated adequate interrater reliability; kappa exceeded 0.85 for depression items on the SCID and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(8). All subjects were required to have no active medical problems, no weight loss of 5 lb or greater in the previous month, and no use of any medications for 2 weeks. Major depressive disorder patients were also required to have: 1) a diagnosis of unipolar major depressive disorder in a current depressive episode without psychotic features, 2) a minimum score of 21 on the 21-item Hamilton depression scale, 3) a minimum score of 7 on the Thase Core Endogenomorphic Scale

(9), 4) no use of fluoxetine within the past 6 weeks, 5) no use of electroconvulsive therapy within the past 6 months, and 6) no drug or alcohol abuse within the past 6 months. Comparison subjects were also required to have no history of psychiatric disorders and no first-degree relatives with axis I disorders, according to the Research Diagnostic Criteria family history assessment

(10). Standard dietary restrictions, described previously

(11), were observed. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

The protocol was conducted in General Clinical Research Centers at Stanford University Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Washington University School of Medicine. Subjects had an intravenous line placed in each arm. Baseline HPA axis hormone levels were monitored for 24 hours; the results of this baseline study have been reported elsewhere

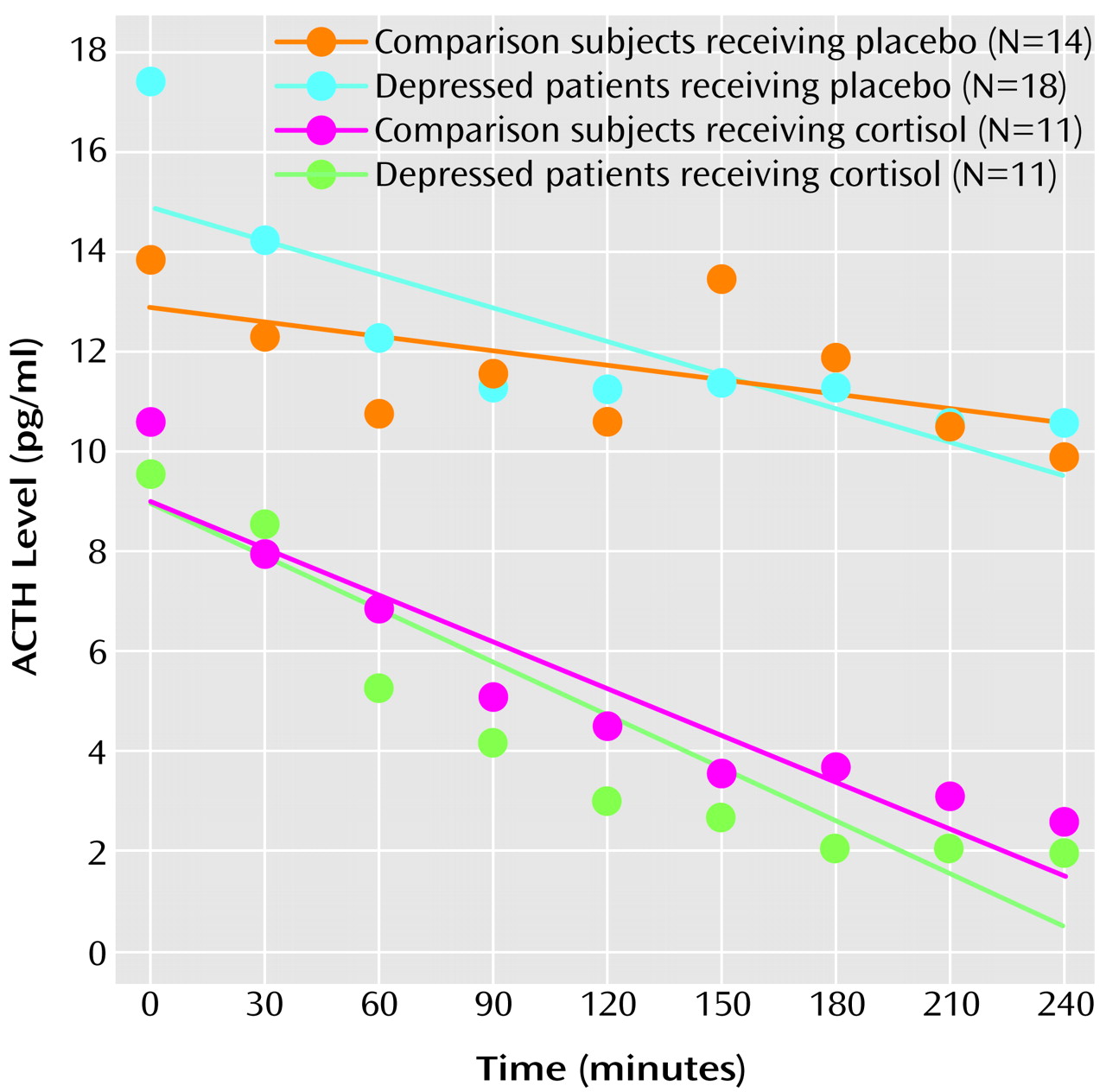

(11). Subsequently, at 7:00 p.m., blood was drawn through an intravenous line to measure cortisol and ACTH levels. The subjects were then randomly assigned to receive 15 mg of cortisol (hydrocortisone sodium succinate) or placebo, infused over 2 hours beginning immediately after the 7:00 p.m. baseline blood draw. Cortisol and placebo were administered by using a double-blind procedure. Every 30 minutes from 7:30 p.m. to 11:00 p.m., blood was drawn through the intravenous line not used for the infusion to measure cortisol and ACTH levels. Some subjects were randomly assigned to receive CRF instead of cortisol or placebo, and these results are not reported here. Cortisol levels were determined by radioimmunoassay

(12) and ACTH levels by immunoradiometric assay

(12) in the Endocrinology Laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

For each subject individually, ACTH levels from 7:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. were modeled, by using a least squares procedure, as having a linear decline, an assumption based on the known diurnal variation of HPA axis activity

(13). The ACTH response to administration of cortisol or placebo was represented by the slope of the modeled linear decrease. Values of the ACTH slope were subjected to a two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), in which diagnosis (major depressive disorder versus no psychiatric disorder) and treatment (cortisol versus placebo) were factors and the 7:00 p.m. baseline ACTH level, sex, and age were covariates. The hypothesis that patients with major depressive disorder have an abnormal ACTH response to cortisol was tested by examining the effect of the interaction of diagnosis and treatment.