The incidence of bipolar illness in patients initially identified as having unipolar depression remains an understudied area of outcome in mood disorders research. In the classical literature, Kraepelin

(1) broadly defined manic-depressive illness as including “the greater part of the morbid states termed melancholia” (p. 1). In modern times, large-scale estimates of the rate of conversion from unipolar depression to eventual mania seldom exceed 5%–10% in patients originally identified as having unipolar depression

(2,

3), although there have been reports

(4,

5) of mania arising in as many as 70%–83% of initially depressed patients. There have been few long-term follow-up studies from which to reliably estimate the cumulative proportion of depressed individuals who progress from unipolarity to bipolarity. Moreover, there is little contemporary information on estimating the risk for developing eventual mania after a depressive episode. The current study was designed to provide data on the longitudinal development of mania or hypomania in a large cohort of young adult patients originally hospitalized for unipolar depression, who were then studied prospectively at five consecutive follow-ups over 15 years.

The rate of unipolar-to-bipolar conversion has been shown to vary across depressive subpopulations. Among depressed outpatients, new-onset bipolar illness has been found in up to 20% of individuals followed for at least 6 years

(6). In depressed adolescents, follow-up studies have shown somewhat higher conversion rates, ranging from 19% to 37%

(7–

10). Cross-cultural studies have shown switch rates as high as nearly 40% in follow-ups from 3 to 13 years’ duration

(11).

1. What is the proportional risk for new-onset mania or hypomania over 15 years among patients formerly hospitalized for unipolar depression?

2. What clinical features may be associated with the eventual development of bipolarity among unipolar depressed patients?

3. To what extent is antidepressant use longitudinally associated with conversion from unipolar depression to bipolar illness?

Results

Development of Mania or Hypomania

By the time of the 15-year follow-up, a total of 30 (41%) of the 74 patients had experienced either a manic or hypomanic episode. A full manic episode occurred for 11 (15%) of the 74 patients, while one or more distinct hypomanic episodes occurred for an additional 19 patients (26%). Among patients who met the criteria for polarity conversion, based on data from the year preceding each follow-up, 20% (14 of 70) had one manic or hypomanic episode, 12% (nine of 75) had two manic or hypomanic episodes, 7% (five of 71) had three manic or hypomanic episodes, and 3% (two of 67) had four manic or hypomanic episodes by the end of the 15-year follow-up period.

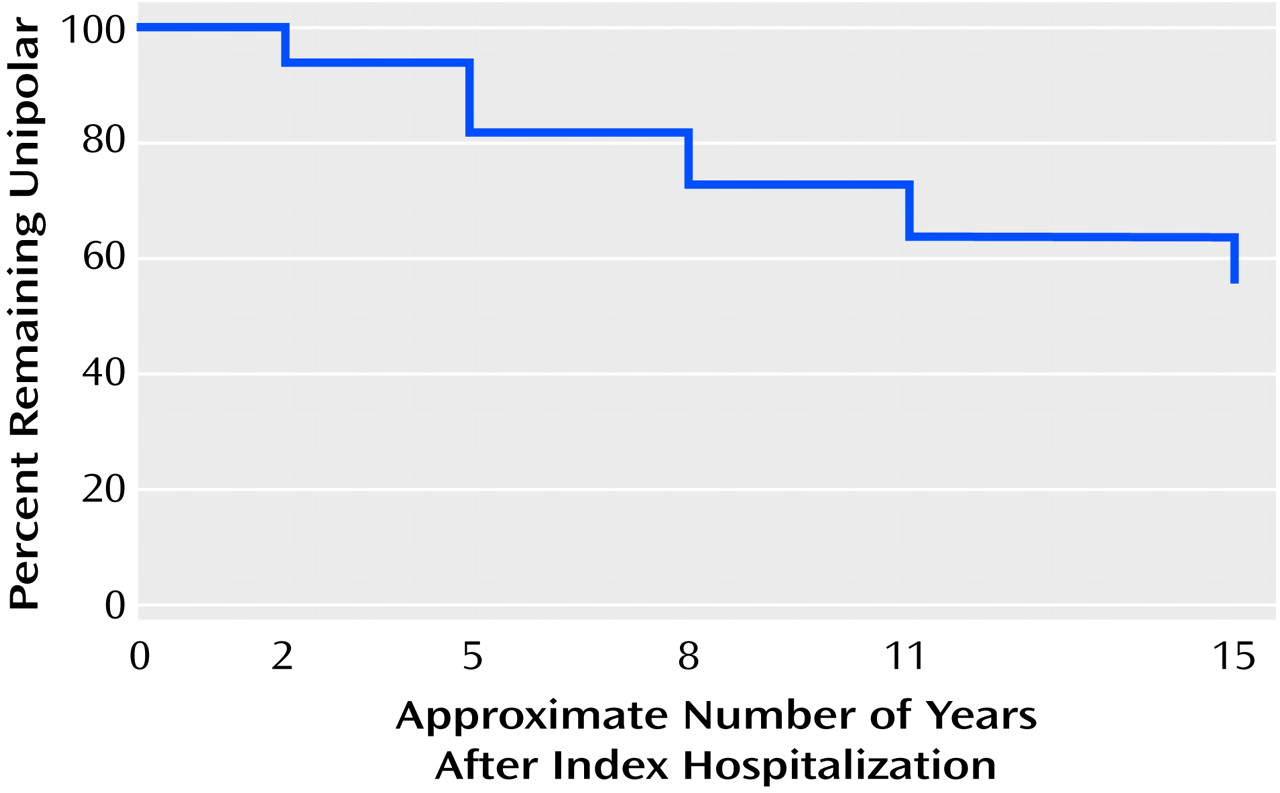

Figure 1 presents the Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for remaining unipolar (i.e., no diagnosis of either mania or hypomania) during the 15-year study period.

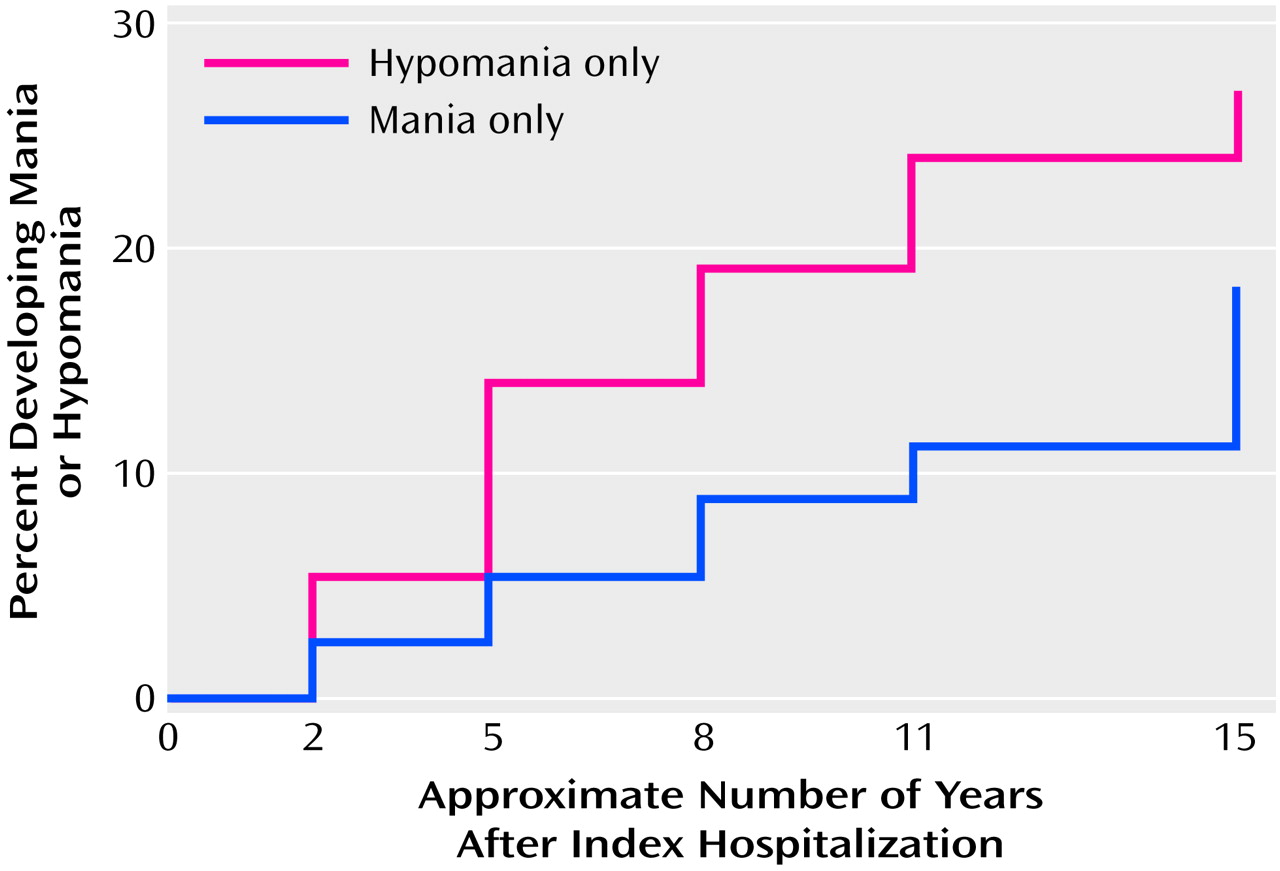

Figure 2 depicts the Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for polarity conversion to mania and hypomania as separate entities. A cumulative proportion of 45% of subjects converted to either mania or hypomania during the study period (

Figure 1). Within the study cohort, 19% had at least one full manic episode, and 27% had one or more hypomanic episodes without full mania (

Figure 2).

We further sought to determine whether full mania and hypomania occurred as independent phenomena or were more likely to arise in the same patient at different points in time. Among the total of 30 patients who developed either mania or hypomania, only five (17%) showed evidence for both clinical entities at two or more separate follow-up periods, while the remainder (25 patients, or 83%) experienced either mania or hypomania only across the five follow-up assessments.

Approximately one-half (45%) of the 11 patients who had a full manic episode during the 15-year study also had a hypomanic period during one or more of the five follow-up periods (N=5). Among the 24 patients who had a hypomanic episode, a lower percentage (21%, five of 24) were among the group who also had a full manic episode during the 15-year study. Of the 19 patients who had hypomania alone, nearly one-half (47%, nine of 19) met the RDC for hypomania at two or more separate follow-ups.

Based on the survival analyses, the conditional probabilities of polarity conversion to either hypomania or full mania during each follow-up interval (i.e., index admission to the first follow-up, first to second follow-up, second to third follow-up, third to fourth follow-up, or fourth to fifth follow-up), given no polarity conversion before each respective interval, were 0.08, 0.12, 0.12, 0.09, and 0.15. For hypomania conversions alone, the conditional probabilities for each of the preceding intervals were 0.05, 0.09, 0.06, 0.07, and 0.04. For full mania conversions alone, the conditional probabilities for each of these intervals were 0.03, 0.03, 0.04, 0.01, and 0.09. No substantial differences in conversion rates were observed among individual follow-up periods.

Naturalistic Pharmacotherapy

The use of antidepressant medications at one or more follow-ups before any mania or hypomania was noted for 14 (47%) of the 30 of the patients who eventually revealed a bipolar course and for 14 (32%) of the 44 patients who remained unipolar (χ2=1.02, df=1, p=0.31). Antidepressant use without a mood stabilizer before conversion to bipolarity was observed in nine (35%) of 26 patients who ultimately had a bipolar course, as compared to 11 (27%) of 41 patients who never became manic or hypomanic (χ2=0.46, df=1, p=0.50). Manic or hypomanic episodes that were unambiguously preceded by exposure to antidepressant medications were observed in four (20%) of the 20 evaluable patients who showed polarity conversions.

The patients who eventually met the criteria for mania or hypomania were more likely to be taking a mood stabilizer (lithium, divalproex, and/or carbamazepine) at some time during the follow-up period than were patients who did not switch polarity (χ2=8.24, df=1, p=0.004). However, fewer than one-half of those who displayed signs of bipolarity received a mood stabilizer (43%, 13 of the 30 converters) at any of the five follow-up assessments.

We also compared pharmacotherapy regimens for all subjects during the year preceding each follow-up. Antidepressant medications were being taken by nine (13%) of the 68 subjects with complete medication data at the 2-year follow-up, eight (11%) of the 72 evaluable subjects at the 5-year follow-up, 11 (15%) of the 74 subjects at the 8-year follow-up, 18 (25%) of the 71 evaluable subjects at the 11-year follow-up, and 17 (25%) of the 68 evaluable subjects at the 15-year follow-up. Neuroleptics were being taken by 10 (15%) of the 68 evaluable subjects at the 2-year follow-up, 11 (15%) of the 72 evaluable subjects at the 5-year follow-up, 12 (16%) of the 74 subjects at the 8-year follow-up, 14 (20%) of the 71 evaluable subjects at the 11-year follow-up, and 10 (15%) of the 68 evaluable subjects at the 15-year follow-up. The proportions of subjects who were taking a mood stabilizer (i.e., lithium, divalproex, or carbamazepine) numerically rose steadily, but did not differ significantly, across the five follow-ups: five (7%) of the 68 evaluable subjects at the 2-year follow-up, six (8%) of the 72 evaluable subjects at the 5-year follow-up, seven (9%) of the 74 subjects at the 8-year follow-up, 10 (14%) of the 74 subjects at the 11-year follow-up, and 12 (18%) of the 68 evaluable subjects at the 15-year follow-up.

Mixed-effect logistic regression models indicated that there were no significant linear effects of assessment time over the course of follow-up on the use of each of the preceding medication classes (for antidepressants: z=0.90, p=0.37; for neuroleptics: z=–1.31, p=0.19; for mood stabilizers: z=0.15, p=0.88).

Factors Associated With Development of Mania

We examined associations between several independent variables (chosen on the basis of their hypothesized clinical significance) and polarity status during the follow-up period (sustained unipolarity versus hypomania versus full mania). Among these variables, polarity conversion was significantly associated with the presence of psychosis at the index depressive episode: 80% of the 10 initially psychotically depressed patients showed signs of eventual bipolarity (four of 10 with hypomania only and an additional four of 10 with full mania), as contrasted with 15 (23%) of the 64 initially nonpsychotic patients who became hypomanic and seven (11%) who became fully manic (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U=482.0, p=0.003). In addition, among the 51 subjects with complete data on family history of affective illness, a family history of bipolar disorder was nonsignificantly associated with eventual mania or hypomania; two (33%) of the six patients with a positive family history became hypomanic and one (17%) of the six became fully manic, while among the 45 patients without a family history of bipolar illness, 10 (22%) became hypomanic and five (11%) became fully manic (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U=157.5, p=0.058).

No significant associations were observed between sustained unipolarity versus eventual hypomania versus eventual full mania and sex, comorbid substance abuse or dependence, or age at first episode of mood disorder. Eight (28%) of the 29 men became hypomanic, and four (14%) became fully manic, contrasted with 11 (24%) of the 45 women who became hypomanic and seven (16%) who became fully manic (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U=655.5, p=0.98). Complete data on substance abuse or dependence at index hospitalization were available for 38 subjects. Among the 21 patients with comorbid substance abuse or dependence at index hospitalization, six (29%) became hypomanic during follow-up and three (14%) became fully manic, whereas four (24%) of the 17 patients without substance abuse or dependence became hypomanic and two (12%) became fully manic (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U=192.0, p=0.64). Complete data on age at first affective episode were available for 31 subjects. For the 27 whose first episode occurred before the age of 25 years, six (22%) became hypomanic during follow-up and three (11%) became fully manic, while none of four patients whose initial episode occurred at or after age 25 became hypomanic and two (50%) became fully manic) (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U=39.0, p=0.33).

Discussion

The findings in this young cohort of patients originally hospitalized for unipolar depression, followed five times over 15 years, indicate that a relatively high cumulative proportion (45%) manifested signs of one or more manic or hypomanic periods at some point during these 15 years. These data suggest a somewhat higher incidence than previously reported for the eventual development of mania or hypomania among patients who are originally identified as having depression. In fact, these findings may

underestimate the magnitude of polarity switches, since the ratings were based on systematic assessments of affective syndromes for the 1 year preceding each follow-up assessment, combined with data on course of illness, treatments, and narrative clinical material obtained over the 15-year period. In contrast to findings from earlier studies

(2,

7,

25), the risk period for developing mania may extend somewhat longer than the first 5 years after an index episode of depression.

A relatively low switch rate (5.2% for bipolar I, 5.0% for bipolar II) was reported among 381 initially unipolar depressed patients followed over 10 years in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Study on the Psychobiology of Depression

(26). The present cohort differed from this group in that the majority of the current patients (86%) were first- or second-admission patients, many of whom were in their early to mid 20s at index hospitalization. By contrast, a smaller percentage of subjects who entered the NIMH collaborative study were under age 30, and a number of depressed subjects entered that cohort as outpatients rather than inpatients. It is possible that depressed patients at greater risk for conversion to bipolarity may do so before age 30 and may be more severely ill (i.e., hospitalized, with psychotic features). Indeed, Akiskal et al.

(27) observed that an illness onset before age 25 years carried a predictive value of 69% (sensitivity 71%, specificity 68%) in identifying depressed patients with an eventual bipolar outcome. In the present study, while this age distinction did not discriminate polarity converters from nonconverters, the small number of patients with first episodes occurring later than age 25 (10% of the cohort) may have precluded detection of such age differences.

Because the subjects in the current group included those who were available for follow-up assessments throughout the 15-year period, the findings may be less generalizable to young adult patients who become lost to follow-up soon after an initial hospitalization for major depression. Since no apparent decremental trend was observed in polarity conversion rates during the 15-year follow-up period, it is possible that the long-term risk for polarity conversion would differ in a more heterogeneous (or initially less severely ill) group of depressed patients. It is also likely that even in the early 1980s, hospitalization could have been viewed as a proxy for severity in patients with depression, making the current findings most pertinent to patients with more severe initial forms of major depression.

Bipolar II disorder has been hypothesized to differ from bipolar I disorder as a separate nosologic entity with unique family genetics and a low probability of progression to bipolar I mania

(26). The current findings support this view, inasmuch as the majority of patients who developed hypomania during the follow-up period did not also demonstrate full mania. The rate of conversion to hypomania in the present study (27% at 15 years) is higher than that reported in an 11-year follow-up study of initially unipolar depressed patients (8.6%)

(27), although as noted previously, the lower rate of conversion to either mania or hypomania in the NIMH collaborative study cohort may reflect a higher mean cohort age at study entry. In the current study, no significant differences between converters to hypomania versus mania were identified in any of the independent variables tested for their association with polarity change.

Although the diagnostic reliability of bipolar II disorder has historically been a subject of some debate, the literature has suggested that high interrater reliability may be achieved for hypomanic episodes through the use of structured interviews by experienced clinical raters

(28,

29). The present findings affirm these observations. Moreover, nearly one-half of the patients identified with bipolar II disorder at follow-up met the RDC for hypomania on two or more separate occasions, lending further support to the presence of a bipolar diathesis. While hypomania may pose a diagnostic challenge and could in theory be both under- and overrated by some clinicians, the use of structured clinical interviews (such as the SADS) by experienced clinical raters in the present study may significantly help to minimize this potential.

The current findings are strongly consistent with prior observations that psychosis in young depressed patients is associated with the eventual development of mania or hypomania. Previous studies attempting to identify risk factors associated with unipolar-to-bipolar conversion, or the stability of polarity distinctions between unipolar and bipolar disorder, have shown that mania is common among patients with sudden onset

(8,

26), early onset

(6,

26), psychosis

(8,

25), and psychomotor retardation

(6,

8). Familial mania has been linked with bipolarity in some studies

(6,

26,

30) but not others

(3), while multiple prior episodes have been associated with eventual polarity switches by some investigators

(3) but not others

(26).

In the present cohort, evidence for antidepressant-induced mania was apparent in 20% of the individuals who became manic or hypomanic, and polarity conversions were

not more likely to occur in association with antidepressant use (whether or not in conjunction with a mood stabilizer) than spontaneously. Elsewhere, antidepressant use has been reported to induce mania in approximately one-third of patients with known bipolar illness

(31,

32), although less is known about the induction of mania in depressed patients without an existing history of demonstrated bipolar illness. For example, Bunney

(33) reported an approximate 9.5% risk for cycling induced by tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors among previously “nonbipolar” depressed patients, although estimates based on the use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors or other newer-generation antidepressants have not been well established. Similarly, lithium has been reported to confer some degree of protection against mania induced by tricyclic antidepressants

(34,

35), but more extensive data are needed on the protective value of lithium and other mood stabilizers in depressed patients with high risk for eventual conversion to bipolarity. Few subjects in the current study had taken mood stabilizers before or with antidepressants, limiting the ability to estimate the effect of prophylactic mood stabilizers on mania otherwise preceded by antidepressant use.

Stoll and colleagues

(36) found that antidepressant-associated manic episodes were milder and shorter than spontaneous manic episodes among inpatients with known bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. These authors observed that antidepressant-associated mania may be a clinical entity distinct from spontaneous mania. In this regard, current treatment practice guidelines

(37) do not uniformly advise the use of mood stabilizers for instances in which mania or hypomania arises solely in the context of recent antidepressant exposure, especially when antidepressant discontinuation alone ameliorates manic or hypomanic symptoms. In the present cohort, the relatively small number of manic or hypomanic episodes clearly preceded by antidepressant exposure precluded a meaningful comparison of clinical characteristics that might differentiate spontaneous from medication-associated affective cycling. Further studies are needed to clarify risk factors for antidepressant-associated mania.

The current data support recent observations that a sizable minority of depressed patients are likely to demonstrate an eventual bipolar course, but clinicians may not regularly initiate mood stabilizer pharmacotherapy for them

(12). The data strongly support the view that late-adolescent and young adult patients hospitalized for psychotic depression, potentially with a family history of bipolar illness, carry a high risk for developing signs of bipolar disorder within at least the first 15 years after an index episode of depression, with a remarkably high percentage of these psychotically depressed individuals demonstrating signs of mania or hypomania at one or more subsequent time periods.