The superior temporal gyrus has been of particular interest in schizophrenia research since Barta et al.

(1) and Shenton et al.

(2) observed that it is associated with hallucinations and thought disorder. The involvement of the superior temporal gyrus in language-related schizophrenic symptoms has been confirmed by subsequent structural and functional imaging studies

(3–

7). Furthermore, the presence of premorbid speech abnormalities suggests the possibility of superior temporal gyrus dysfunction predating the onset of schizophrenia. Premorbid language problems in schizophrenic subjects are three times more likely than in healthy subjects

(8), and their prevalence may be higher in patients with early-onset (during childhood and adolescence) schizophrenia

(9).

It is not clear whether the degree or nature of superior temporal gyrus abnormalities is modified by the age at onset of the disorder. Morphometric studies in patients with adult-onset schizophrenia have reported mainly left-sided volume deficits compared to healthy subjects

(1,

2,

4,

5,

10–

12). In contrast, relative to healthy comparison subjects, Marsh et al.

(11) reported lower bilateral gray matter volume of the superior temporal gyrus in 56 male patients with chronic schizophrenia with early onset, and Jacobsen et al.

(13) found superior temporal gyrus enlargement in 21 adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia. Jacobsen et al. later reported a bilateral reduction in superior temporal gyrus volume in a group of 10 patients from their initial cohort rescanned after an average interval of 2 years

(14).

In the present study, we compared superior temporal gyrus volumes in adolescents with recently diagnosed schizophrenia to those of matched healthy volunteers. Our main aims were to examine 1) whether the earlier age at illness onset was associated with greater deviance of superior temporal gyrus volume and 2) whether the role of the superior temporal gyrus in the pathogenesis of language-related positive symptoms was similar to that seen in patients with adult-onset schizophrenia.

Results

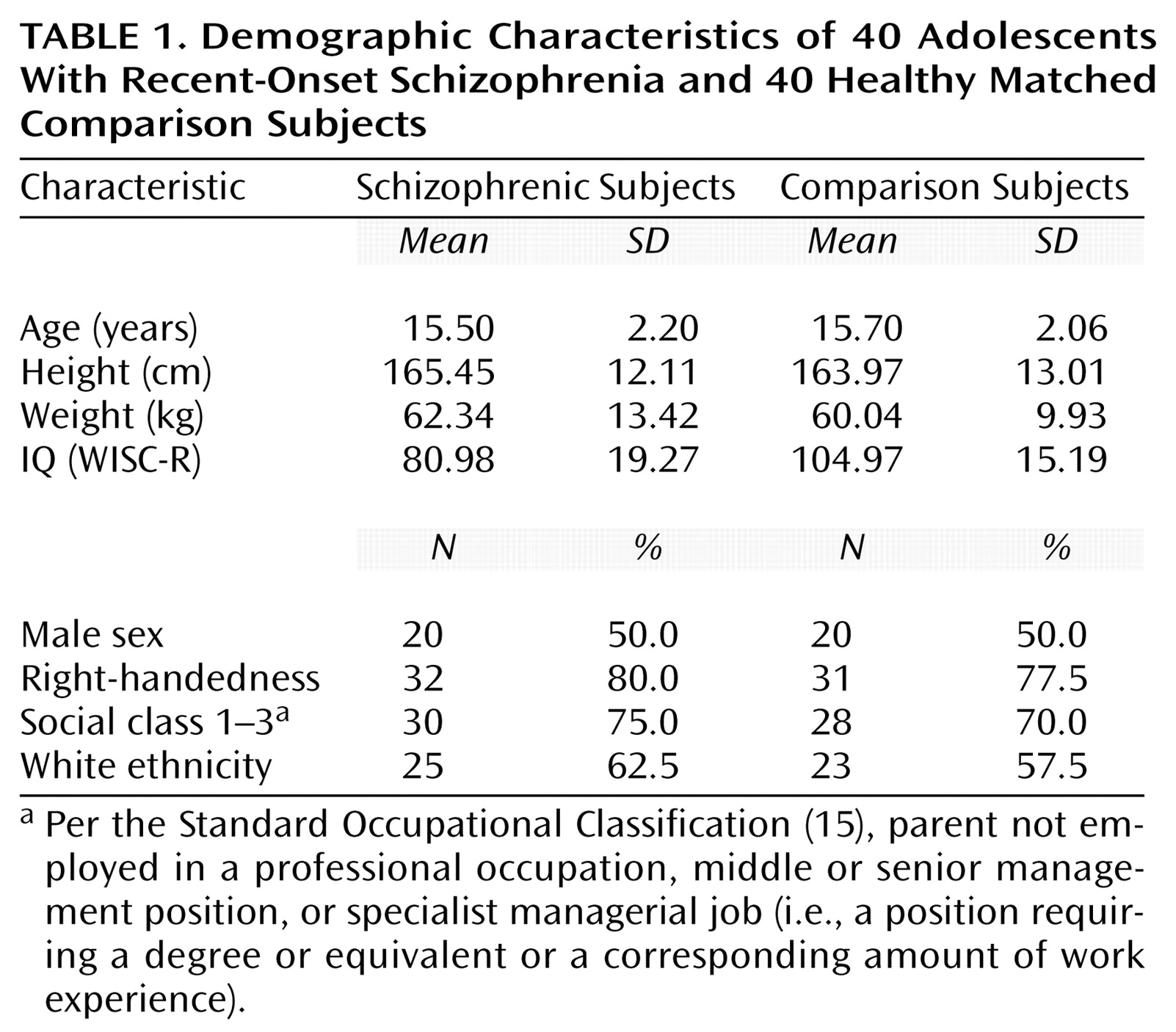

There were no group differences in age (t=–0.4, df=78, p=0.60), gender (χ

2=0.2, df=1, p=0.50), ethnic origin (χ

2=4.1, df=3, p=0.10), handedness (χ

2=2.2, df=2, p=0.30), or parental social class (χ

2=4.9, df=4, p=0.20) (

Table 1).

The patients’ mean age at assessment was 15.5 years (SD=2.0). Their mean age at onset of psychosis was 14.1 years (SD=2.1), and their mean duration of illness was 16.0 months (SD=14.4). Thirty-two patients had been receiving regular antipsychotic medication for a mean of 11.1 months (SD=14.8), mostly atypical antipsychotics (62.8%), while the remaining eight were medication free at the time of scanning.

There was no group difference in the mean age at spontaneous production of first words between the volunteers (mean=12.59 months, SD=5.81) and the patients (mean=15.20 months, SD=7.11) (t=–1.44, df=78, p=0.15). However, significantly more patients had received treatment for speech problems (12 patients versus three volunteers) (p=0.004, Fisher’s exact test).

Structural MRI Data

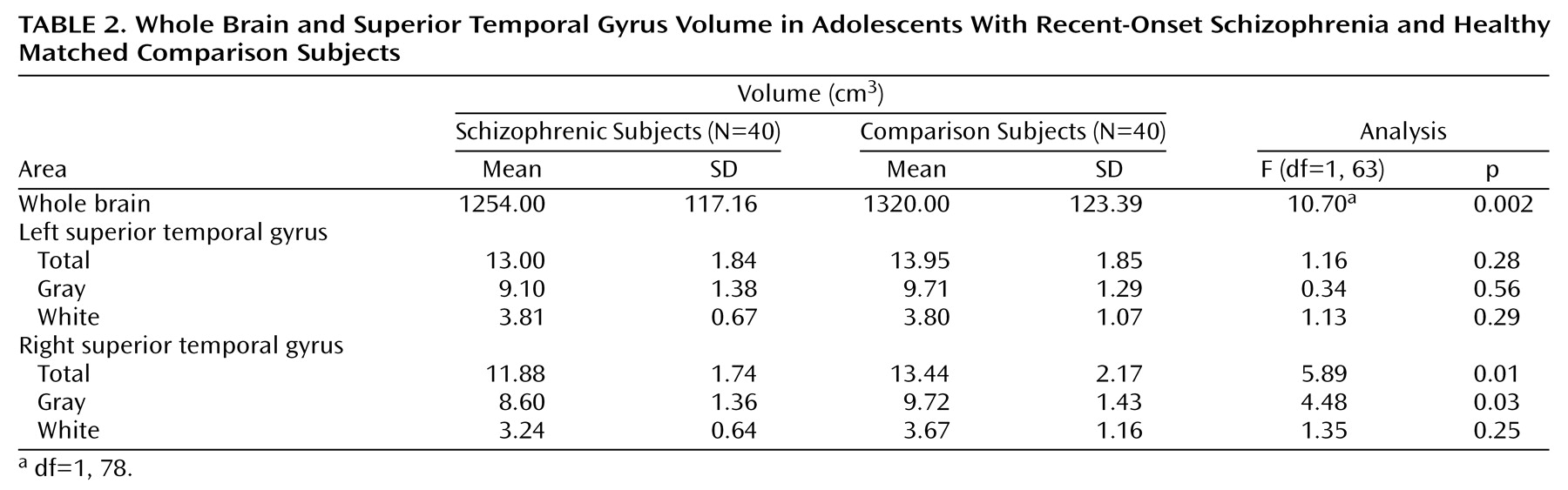

Compared to the volunteers, patients had significantly lower whole brain volumes (

Table 2). There was an effect of gender (F=37.80, df=1, 76, p<0.0001), with male subjects having larger volumes, but no gender-by-diagnosis interaction (F=0.03, df=1, 76, p=0.86). General linear model repeated measures analysis with side as the repeated measure; diagnosis, gender, and handedness as between-subject factors; and whole brain volume as covariate revealed a significant side-by-diagnosis interaction for the total superior temporal gyrus volume (F=8.39, df=1, 63, p=0.005). The interactions of side by gender (F=2.05, df=1, 63, p=0.15); side by handedness (F=0.94, df=2, 63, p=0.39); or side by diagnosis, gender, and handedness (F=2.75, df=1, 63, p=0.10) were not significant. Subsequent, univariate analyses revealed that the effect of diagnosis was significant for volume of the right superior temporal gyrus but not the left (

Table 2).

Similarly, there was a significant side-by-diagnosis interaction for the gray matter volume of the superior temporal gyrus (F=5.64, df=1, 63, p=0.02). The interactions of side by gender (F=2.35, df=1, 63, p=0.13); side by handedness (F=0.55, df=2, 63, p=0.58); or side by diagnosis, gender, and handedness (F=3.53, df=1, 63, p=0.06) were not significant. The effect of diagnosis was significant for the gray matter volume of the right superior temporal gyrus but not the left (

Table 2).

There was a significant side-by-diagnosis interaction for white matter volume as well (F=5.91, df=1, 63, p=0.01). The interactions of side by gender (F=0.49, df=1, 63, p=0.48); side by handedness (F=1.22, df=2, 63, p=0.30); or side by diagnosis, gender, and handedness (F=0.40, df=1, 63, p=0.52) were not significant. There was no effect of diagnosis on white matter volume for either side (

Table 2).

To further explore the issue of superior temporal gyrus asymmetry, laterality coefficients were calculated by using the following formula: (left–right)/0.5(left+right). This coefficient was entered in a univariate ANOVA as the dependent variable with diagnosis, gender, and handedness as fixed factors. This revealed an effect of diagnosis (F=9.53, df=1, 64, p=0.003) but not of gender (F=2.11, df=1, 64, p=0.15) or handedness (F=0.95, df=2, 64, p=0.40). The interactions between gender and diagnosis (F=2.57, df=1, 64, p=0.11) and handedness and diagnosis (F=1.86, df=2, 64, p=0.16) were not significant. The interactions between gender and handedness (F=2.68, df=2, 64, p=0.07) and for diagnosis, gender, and handedness (F=3.07, df=1, 64, p=0.08) failed to reach statistical significance. This finding of greater leftward laterality in patients than in healthy volunteers was consistent with our aforementioned finding of lower right-side total and gray matter superior temporal gyrus volumes in the patients with schizophrenia.

Finally, in order to examine the possible confounding effect of medication, the volume of the superior temporal gyrus was compared between schizophrenic patients divided into three subgroups according to treatment with typical or atypical antipsychotics or no medication. No significant effect of medication was found (F=1.56, df=4, 74, p=0.19). In addition, no correlation was found between medication duration and the volume of either the left or the right superior temporal gyrus (left: r=0.17, df=40, p=0.11; right: r=0.008, df=40, p=0.94).

Correlations Between Volumetric Measures and Clinical Variables

We examined the correlation between the volumetric measures and the scores from the items “hallucinatory behavior” and “conceptual disorganization” derived from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Neither score correlated with whole brain volume (hallucinatory behavior: r=–0.13, df=40, p=0.42; conceptual disorganization: r=–0.06, df=40, p=0.71). Both scores were negatively correlated with bilateral total volume of the superior temporal gyrus. The correlations were significant on the right (hallucinatory behavior: r=–0.31, df=40, p=0.006; conceptual disorganization: r=–0.24, df=40, p=0.03) but failed to reach statistical significance on the left (hallucinatory behavior: r=–0.12, df=40, p=0.06; conceptual disorganization: r=–0.11, df=40, p=0.09). For the gray matter volume of the superior temporal gyrus, significant bilateral correlations were seen for hallucinatory behavior (right: r=–0.39, df=40, p=0.0001; left: r=–0.27, df=40, p=0.02) and conceptual disorganization (right: r=–0.34, df=40, p=0.03; left: r=–0.22, df=40, p=0.05). No significant correlations were found between white matter volume and either hallucinatory behavior (right: r=–0.15, df=40, p=0.20; left: r=0.04, df=40, p=0.70) or conceptual disorganization (right: r=–0.06, df=40, p=0.58; left: r=0.11, df=40, p=0.34). Of these correlations, only the one between the right gray matter volume and hallucinatory behavior would have survived Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

No correlation was found between age and superior temporal gyrus total volume (right: r=0.10, df=40, p=0.51; left: r=0.12, df=40, p=0.43). However, there was a positive bilateral correlation between age at onset of psychosis and both total volume (right: r=0.31, df=40, p=0.04; left: r=0.33, df=40, p=0.03) and gray matter volume (right: r=0.34, df=40, p=0.03; left: r=0.35, df=40, p=0.03). No significant correlations were found between age at onset of psychosis and the volumes of the whole brain (r=0.16, df=40, p=0.29) or the white matter of the superior temporal gyrus (right: r=0.05, df=40, p=0.74; left: r=–0.01, df=40, p=0.93). None of these correlations would have survived Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Discussion

We found total and gray matter volumes of the right superior temporal gyrus that were lower in adolescents with recent-onset schizophrenia than in healthy comparison volunteers. The total and gray matter volumes of the superior temporal gyrus on both sides correlated positively with age at onset of psychosis. Bilateral gray matter volume of the superior temporal gyrus was negatively correlated with the severity of hallucinations and conceptual disorganization.

Our finding of right-sided superior temporal gyrus deficits was unexpected. Previous studies of this structure in adult-onset schizophrenia have suggested either left-sided deficits or no differences

(1,

2,

5,

21–

24). Holinger et al.

(25) reported right-sided superior temporal gyrus deficits, but they examined only left-handed male subjects (eight with schizophrenia and 10 volunteers).

The study that is most directly comparable to ours is that of Jacobsen et al.

(13). They examined the volume of the superior temporal gyrus in 41 volunteers and 21 patients who had developed schizophrenia in childhood but were assessed in adolescence (mean age at the time of their MRI scan=14.6 years). In this study, the superior temporal gyrus was larger bilaterally in patients but more so on the right after an adjustment was made for whole brain volume. There are differences in study populations and brain image analysis methods that could explain the discrepancy between their findings and ours, at least in part. Their study consisted of patients whose mean age at onset of psychosis was 10.2 years (SD=1.5), 4 years earlier on average than in the present study. In addition, their patients were selected on the basis of treatment resistance, and a number were later found to have comorbid neurological or pervasive developmental disorders

(14).

Clinical Correlates of Superior Temporal Gyrus Abnormalities

Morphometric studies of adult-onset schizophrenia point to a negative correlation between left superior temporal gyrus volume and thought disorder or hallucinations

(1,

2,

4,

5,

10,

24). Functional imaging studies, however, have revealed a bilateral involvement of the superior temporal gyrus in the pathogenesis of such symptoms

(6,

7). Lennox et al.

(7) and Dierks et al.

(6) found that during auditory hallucinations, activation spreads to a wide area, including both the right and left superior temporal gyri. This evidence suggests that in adult-onset schizophrenia, there is bilateral superior temporal gyrus dysfunction with morphometric abnormalities being prominent on the left.

We also found an inverse relationship between the severity of hallucinations and thought disorder and bilateral superior temporal gyrus volumes. This relationship was significant on the right but failed to reach statistical significance on the left. Therefore, although the direction of the relationship is the same as seen with adult-onset cases, the degree of lateralization of the effect is different. This is also supported by longitudinal data from 10 adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia in which higher positive symptom scores at baseline predicted larger volume deficits in the right posterior superior temporal gyrus at 2-year follow-up

(14).

Neurodevelopmental Considerations

Although our findings require replication, it is possible that predominately right-sided superior temporal gyrus pathology is indeed a feature of early-onset schizophrenia. The right hemisphere develops earlier and more rapidly than the left

(26). Because of this, right-sided brain abnormalities result from particularly early insults and are associated with more widespread brain pathology

(26). As early insults are associated with a lower likelihood of survival, conditions with predominantly right-sided developmental abnormalities are uncommon

(26).

It could be argued that such an early developmental deviance could be associated with the early onset of schizophrenia in our study and the predominantly right-sided pathology seen in the superior temporal gyrus. Other features of early-onset schizophrenia also conform to the characteristics of a condition resulting from an early developmental insult. Early-onset schizophrenia is uncommon: only 4.7% of patients have their onset before the 18th year of life

(27). Early onset is also associated with greater severity and higher levels of premorbid social and cognitive abnormalities, particularly in language development

(9,

28) and poor outcome

(29).

Antipsychotic Effects

There is increasing awareness of the effect of antipsychotics on brain morphology. This has been confirmed for the striatum, in which volumetric increases have been associated with exposure to typical but not atypical antipsychotics

(30–

32). Treatment-related changes in brain morphology might be quite widespread. For example, exposure of primates to typical and atypical antipsychotics leads to glial proliferation and increases in cortical thickness in the prefrontal cortex

(33).

There is theoretical evidence for an effect of antipsychotics on superior temporal gyrus volume measurements. The superior temporal gyrus has a well-differentiated pattern of high concentration of dopamine D

2 receptor expression

(34). Although the density of the D

2 receptor family in the temporal lobe is lower than in the striatum

(35,

36), the level of occupancy following treatment with neuroleptics is similar

(37).

Two longitudinal studies have found changes in superior temporal gyrus volume following alteration or initiation of antipsychotic treatment. Jacobsen et al.

(14) reported a bilateral reduction in the total volume of the superior temporal gyrus and a right-sided reduction in the anterior superior temporal gyrus over a 2-year period in a group of 10 subjects. At baseline, these patients were taking typical antipsychotics, while at the time of their second scan they were treated with atypical antipsychotics, mostly clozapine. There is also a preliminary and as yet unreplicated report of bilateral increases in the volume of the superior temporal gyrus, more pronounced on the right, following initiation of treatment with typical antipsychotics in previously drug-naïve patients

(38). To our knowledge, this is the only study to measure the volume of the superior temporal gyrus in such patients. Patients were already medicated in other first-episode studies of the superior temporal gyrus

(12), while the rest of the literature is based on chronically treated patients

(1,

2,

5,

21–

24,

39).

The existing evidence of a lateralized effect of antipsychotics on superior temporal gyrus volume is limited. However, it does point to antipsychotics as a possible confounding factor in volumetric studies of this brain region in schizophrenia. Subdividing our patient group according to medication status did not reveal significant differences in superior temporal gyrus volume between the different medication groups, but given the small group sizes this finding may be due to a lack of power.

Methodological Considerations

Despite our comprehensive assessment of patients and comparison subjects we cannot exclude the possibility that some individuals in either group may change diagnostic classification in the future. Our volumetric measurements made use of three-dimensional reconstructed images with simultaneous viewing of the structures in three planes. Thus, we were able to overcome the difficulties associated with recognition of superior temporal gyrus boundaries in single-plane measurements. However, raters were not blind to side, although it is unlikely that this influenced the results, since any bias would be in terms of known abnormalities in the left superior temporal gyrus.

In summary, we found right superior temporal gyrus volume deficits in patients with early-onset schizophrenia. This is in apparent contrast to findings from adult-onset cases and may reflect an unusually early neurodevelopmental insult resulting in right-sided brain pathology. We also confirmed that, as in adult-onset schizophrenia, abnormalities in the superior temporal gyrus are related to the severity of hallucinations and thought disorder, which implies continuity with adult-onset schizophrenia in the pathogenesis of these symptoms. However, this association appeared to be less lateralized in early-onset cases.