Memory and executive functions are frequently impaired in depressed elderly patients

(1). These cognitive impairments influence the course of geriatric depression

(2,

3) and may be associated with its pathogenesis

(1).

Resting neuroimaging studies of younger depressed patients have shown left-sided or bilateral hypoactivity in the dorsolateral, inferior, and medial frontal regions as well as the temporal limbic regions, particularly the amygdala

(4–

7). Resting state hypoactivity in the medial prefrontal cortex has been correlated with cognitive impairment

(8). Blunted left cingulate activation has been observed in younger depressed patients performing a response interference task

(9).

Geriatric depression often occurs in the context of age-related brain changes that contribute to its pathogenesis

(10). Therefore, findings in younger adults may not necessarily generalize to the elderly. Functional neuroimaging studies in geriatric depression have reported lower levels of global blood flow, orbitofrontal and inferior temporal regional blood flow decreased

(11,

12), and abnormalities in posterior association cortices

(13). These valuable findings were noted only under resting conditions and yielded limited information on the integrity of neural systems that serve executive functions and memory.

On the basis of clinical findings from elderly depressive subjects and neuroimaging findings from younger adults, we used positron emission tomography (PET) during an activation paradigm (involving a word generation task) in addition to resting state measurements to test the hypothesis that prefrontal and mesial temporal brain malfunction exists in patients with geriatric depression.

Method

The patient group consisted of six right-handed older subjects (four men and two women; mean age=70.7 years, range=59–82) with DSM-IV major depression, a 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(14) score greater than 30, and a Mini-Mental State Examination score greater than 24 (nondemented). The comparison group consisted of five right-handed subjects (three men and two women; mean age=67.6 years, range=62–78). Two patients were drug-free, while one patient each was taking bupropion, venlafaxine, lithium, and risperidone. Exclusion criteria were comorbid axis I diagnosis and axis III diagnosis of medical or neurologic conditions. All subjects signed informed consent.

Mattis Dementia Rating Scale data were obtained from five of six patients and four of five comparison subjects. Differences between patients and comparison groups on neuropsychological subtest scores were assessed with one-tailed t tests. A repeated measure one-way analysis of variance was performed to assess the correlation in patients between specific subtest scores and adjusted regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) during the rest condition as well as the correlation between subtest scores and activation changes in adjusted rCBF for the brain regions with significant between-group activation differences.

A GE Advance PET scanner in three-dimensional mode with interplane septa retracted was used. A high sensitivity [

15O]H

2O (8 mCi) slow bolus rCBF imaging technique

(15) was employed. Cognitive tasks were performed for 60 seconds, starting 10 seconds before the rise in brain time-activity curve. A 90-second acquisition time was used, which reflects the pattern of brain activity during radiotracer deposition. Each subject had 12 scans in one session, four scans in each of the three conditions. The activation condition was a word generation task in response to a computerized auditory presentation of letters at a rate of one every 5 seconds. The control condition required the subjects to repeat letters presented in the same manner as the activation condition. The third condition was a rest condition. The order of scans was counterbalanced within subjects to counteract time and order effects. The scans were performed with eyes closed, lights dimmed, and low levels of ambient noise. Response latency and accuracy were recorded on digital audio tape.

Image analysis with statistical parametric mapping (SPM 96)

(16) was performed on a Sun SPARC Ultra 2 workstation (Sun Microsystems, Mountain View, Calif.). After realignment of images, stereotactic transformation to Talairach space, and smoothing with a 15-mm gaussian filter, group and condition effects were estimated with multiple linear regression according to the general linear model at each voxel, with global flow considered as a potential confounding variable. A contrast was defined to identify areas of relatively lower rCBF in geriatric depressed patients versus comparison subjects, in the activation versus control state, and a z test was performed with 114 residual degrees of freedom over 255 resolution elements. A correlation analysis was also performed to assess the relationship between resting and activation rCBF measures and neuropsychological scores. Probability was estimated according to the theory of random fields

(16). For the activation contrast, all SPM maxima for which z>2.33 (representing a significance level of p<0.01, one-tailed, uncorrected) are reported.

Results

Available neuropsychological data (Mattis Dementia Rating Scale scores) from five of the patients and four of the comparison subjects showed that the patients performed significantly worse on the subtests of memory (one-tailed t test, without assumption of equal variance: t=2.92, df=4, p<0.03), initiation/perseveration (t=2.36, df=4, p<0.04), and conceptualization (verbal and nonverbal similarities) (t=2.11, df=5.21, p<0.05). A nonsignificant difference was noted for the attention subtest scores (t=1.95, df=4.52, p<0.06), and no significant difference was noted for scores on the construction subtest (t=0.88, df=4, p<0.21). Reaction time (t=0.52, df=7, p=0.62) and accuracy (t=–1.54, df=7, p<0.22) in scanning task performance in patients did not differ significantly from those of comparison subjects.

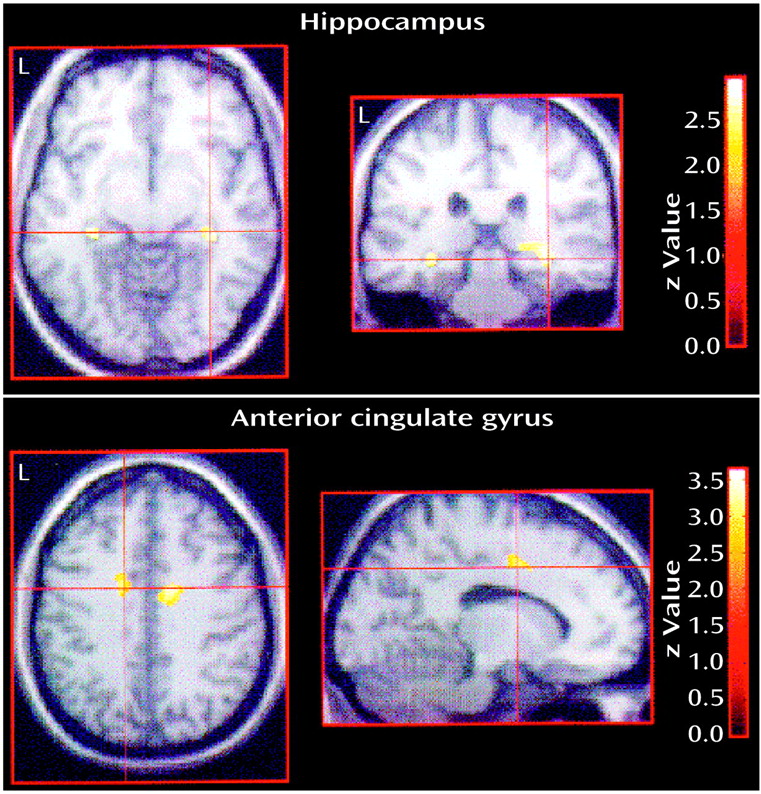

For the contrast that demonstrated lower activity in the depressed elderly group relative to the comparison group during activation (versus the control state), significantly lower rCBF (thresholded at p<0.01, uncorrected) was noted in frontotemporal regions: left anterior cingulate gyrus (x, y, z=–16, 0, 40) (z=3.23, p<0.001), right anterior cingulate gyrus (14, –2, 40) (z=3.43, p<0.001), left hippocampus (–32, –30, –10) (z=2.73, p<0.01), right hippocampus (34, –32, –4) (z=2.93, p<0.01), left insula (–34, –4, 18) (z=3.67, p<0.001), and the right inferior temporal gyrus (Brodmann’s area 20; 66, –1, –28) (z=3.86, p<0.001) (

Figure 1). Inspection of mean adjusted rCBF levels in the cingulate and hippocampal regions indicated a double dissociation, with increasing activity in comparison subjects and decreasing activity in patients.

For patients, considering the hippocampal and anterior cingulate maxima listed above, significant correlations were noted only between memory scores and left hippocampal resting adjusted rCBF (r=0.94, df=3, p<0.05), right hippocampal resting rCBF (r=0.91, df=3, p<0.05), and left hippocampal activation rCBF change (r=0.80, df=3, p<0.05).

Discussion

These data provide preliminary evidence that geriatric depression is associated with bilateral cingulate and hippocampal hypoactivity upon challenge with a word generation task. Given the neurobehavioral functions ascribed to these regions, it is plausible that hypoactivity of the dorsal cingulate is associated with executive and psychomotor symptoms

(17) often prominent in geriatric depression, while bilateral hippocampal hypoactivity is associated with memory impairment

(18) commonly observed in geriatric depression. The patients studied did indeed have memory and initiation/perseveration deficits relative to the comparison subjects. The available memory and initiation/perseveration data from the patients studied help to make additional, more specific statements concerning possible associations between the aforementioned neural and neuropsychological findings. In particular, they implicate resting and activation hippocampal dysfunction (especially on the left) in patients’ memory impairment.

These preliminary findings are limited by the relatively small study group size and potential medication effects in four of the patient subjects. However, the within-subject medication effects were reduced by having the subjects perform the activation and control tasks under identical pharmacological conditions, and the effect across subjects was reduced by partialing out subject-specific effects and by the fact that medicated patients were not all receiving the same class of medication. Hippocampal atrophy has been noted in recurrent major depression

(19). While such structural changes may relate to the current findings, it is notable that the mean adjusted rCBF levels at the hippocampal maxima were as high or higher in patients than they were in comparison subjects. Nevertheless, further studies of larger numbers of unmedicated subjects, with hippocampal volume measures, will be important to assess the generalizability of these findings.