Several studies have examined the efficacy of treatment interventions for anorexia and bulimia nervosa

(1,

2). Collectively, these studies have supported the use of cognitive behavior therapy, antidepressant medication, and, potentially, interpersonal therapy for the treatment of bulimia nervosa but have failed to provide compelling data concerning the treatment of anorexia nervosa

(1). In a review, Keel and Mitchell

(2) noted that controlled treatment outcome studies tended to find that treatment interventions predicted positive bulimia nervosa outcome, whereas naturalistic follow-up studies found treatment interventions to be unassociated with outcome. Possible explanations for this pattern were noted. For example, controlled treatment outcome studies randomly assign women to treatment in order to control for differences among women that could impact outcome. In naturalistic follow-up studies, it is possible that women who seek less treatment have less severe pathology. Indeed, higher levels of comorbidity were found in a clinic-based group than in a community-based cohort of women with bulimia nervosa

(3). Despite the potential importance of this pattern, few studies have investigated predictors of treatment utilization within a group of women suffering from anorexia or bulimia nervosa.

Method

Of 294 women recruited between 1987 and 1991, 246 (84%) participated. At intake, 136 (55%) met DSM-IV criteria for anorexia nervosa, and 110 (45%) met DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa. Additional inclusion criteria were minimum age of 12 years, residence within the Boston area, English speaking, and no evidence of organic brain syndrome or terminal illness. Demographic data have been presented elsewhere

(4). After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

After intake interviews, follow-up interviews were scheduled at 6-month intervals. The median follow-up period was 108 months (minimum=3, maximum=144; first quartile=96, third quartile=120). Thus far, 229 subjects (93%) have been retained.

Eating pathology, other axis I pathology, presence of personality disorders, overall symptom severity, and psychosocial function were assessed at baseline with the following measures: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version

(5), modified to include DSM criteria for anorexia and bulimia nervosa; the Structured Interview for DSM-III Personality Disorders

(6); and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale.

During follow-up assessments, the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation adapted for eating disorders

(4) was used to assess eating pathology, comorbid axis I disorders, Global Assessment of Functioning score, and treatment utilization on a week-by-week basis. Use of the following treatments was assessed: inpatient treatment, individual outpatient psychotherapy, inpatient or outpatient clinician-led group psychotherapy, and medication with antidepressants or anxiolytics.

Psychiatric status ratings were used to code psychopathology. Psychiatric status rating scores range from 1 to 6, with 1 indicating no symptoms and 5 and 6 signifying fulfillment of full diagnostic criteria. Details on the use of this rating scale are presented elsewhere

(4). Lifetime history of comorbid disorders was coded as present or absent on the basis of history at intake and follow-up evaluations. Severity of eating disorder symptoms was calculated from responses to DSM symptoms (e.g., amenorrhea, binge-eating, self-induced vomiting). Scores ranged from 0 to 14; higher scores indicated greater severity. Treatment utilization was calculated in two ways: total number of weeks receiving a specific intervention divided by the number of weeks of follow-up and whether or not treatment was received during each year. Because treatment utilization was not normally distributed, nonparametric tests were employed. Analyses were conducted by using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago) and SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Because of the large number of comparisons, alpha=0.01.

Results

Only 11 women (4%) reported receiving none of the forms of treatment assessed during follow-up. The number of women receiving treatment each year decreased as the duration of follow-up increased. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests revealed that significantly more women received treatment during the first year of the study than in the second year (z=–4.02, df=242, p<0.001), but no significant differences in numbers were found between the second and third years (z=–2.31, df=237, p=0.02), the third and fourth years (z=–2.20, df=235, p=0.03), or the fourth and fifth years (z=–1.10, df=229, p=0.27). Thus, women were most likely to receive treatment during the first year of follow-up. Treatment utilization during a previous year significantly predicted treatment utilization during the subsequent year (χ2=9.56–36.93, df=1, all p<0.00001). As a result of these two patterns, women who received treatment during year 5 of the study had significantly higher treatment utilization for all forms of intervention (z ranged from –3.76 for inpatient treatment to –10.35 for individual therapy, df=229, all p<0.001).

Mann-Whitney U tests demonstrated that women with anorexia nervosa spent significantly more time in inpatient (z=3.10, df=246, p=0.002) and group treatment (z=2.53, df=246, p=0.01) than did women with bulimia nervosa. However, the association between diagnostic status and group treatment was no longer significant after we controlled for inpatient treatment (F=4.80, df=1, 243, p=0.03), and no other forms of treatment differed significantly between women with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (all p>0.05). Among the women with anorexia nervosa, no significant differences were found between those with the restricting subtype and those with the binge-purge subtype for any form of treatment during follow-up (all p>0.25). Severity of eating disorder symptoms during each year significantly predicted treatment utilization during the subsequent year (Kendall’s tau-b=0.15–0.23, df=246, all p<0.01).

Presence of a personality disorder at intake was associated with greater subsequent treatment utilization for all forms of intervention (z ranged from –3.59 for group treatment to –4.38 for inpatient treatment, df=246, all p<0.001). Similarly, Global Assessment of Functioning scores at intake significantly predicted subsequent treatment utilization across all interventions (Kendall’s tau-b ranged from –0.20 for treatment with antidepressants to –0.42 for inpatient treatment, df=246, all p<0.001). Further, Global Assessment of Functioning scores during each year significantly predicted treatment utilization during the subsequent year (Kendall’s tau b=–0.21 to –0.33, df=246, all p values<0.001).

A lifetime history of mood disorders predicted greater utilization of individual psychotherapy (z=–3.07, df=246, p=0.002) and antidepressant medication (z=–3.48, df=246, p=0.0005) over follow-up. However, lifetime histories of substance use and anxiety disorders were not significantly associated with any form of treatment (all p>0.01).

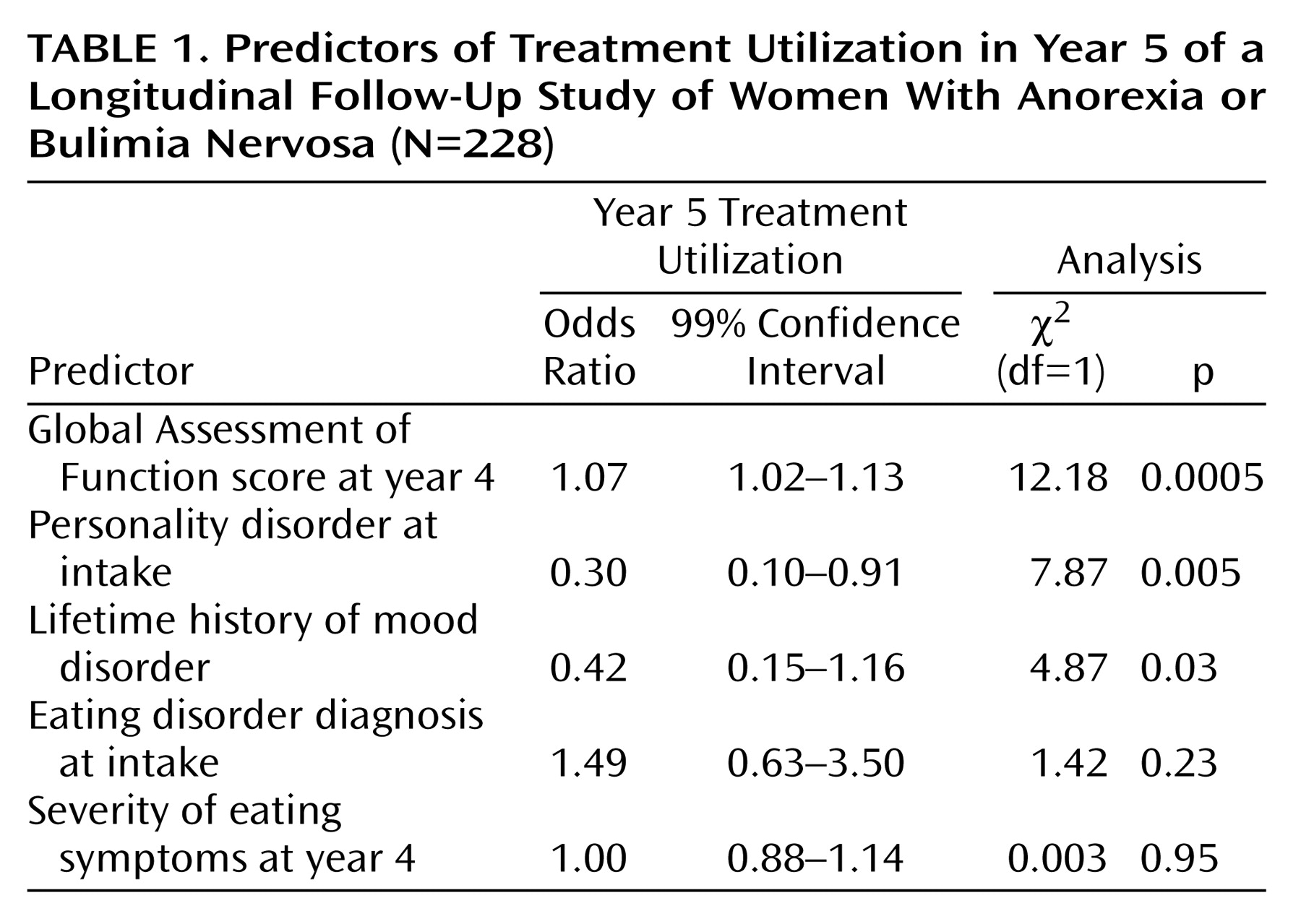

Table 1 presents results of a logistic multiple regression to determine predictors of receiving treatment during year 5 of the longitudinal study. Predicted values did not differ significantly from observed values (Hosmer-Lemeshow C=11.81, df=8, p=0.16).

Discussion

Over 95% of this group of women with eating disorders received some form of treatment during follow-up. Women with anorexia nervosa received more inpatient treatment than did women with bulimia nervosa. However, women with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa did not differ significantly in other forms of treatment. Although lifetime history of mood disorders and eating disorder severity predicted treatment utilization, the strongest predictors of year 5 treatment utilization were a poor Global Assessment of Functioning score in year 4 and a comorbid personality disorder at intake.

Despite several strengths (including a large study group, high retention rate, and careful prospective assessment of treatment utilization), certain limitations should be noted. The present investigation did not address treatment adequacy by evaluating medication doses or treatment duration according to treatment guidelines. Further, treatment utilization by these women may be unrepresentative, since most women were seeking treatment through a tertiary care center. Despite these limitations, significant predictors of treatment utilization were identified.

Our results indicate that women with more severe pathology receive more treatment. This replicates findings from the Collaborative Study of Depression

(7) in which greater episode duration, symptom severity, and worse Global Assessment of Functioning scores predicted greater treatment utilization before intake. Moreover, our results could explain the seeming lack of treatment efficacy outside of controlled treatment outcome studies

(2). Although women may benefit from treatment outside of controlled studies, those women with the most severe and chronic forms of pathology may receive the most care and thus obscure the favorable impact of treatment.