Neurodevelopmental models of schizophrenia posit an important role for aberrant hippocampal morphology in the pathophysiology of the disorder. There is considerable evidence from postmortem

(1–

6) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

(7–

9) studies that patients with schizophrenia have hippocampal structural abnormalities. Moreover, a meta-analysis of 18 structural MRI studies

(10) identified a 4% reduction in bilateral hippocampal volumes in patients with schizophrenia in relation to comparison subjects. Because hippocampal volume reductions have been identified in younger patients experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia

(8), these abnormalities do not appear to be an artifact of long-term exposure to antipsychotic medications or to chronicity of the disorder.

Despite evidence for hippocampal pathology in patients with schizophrenia, few studies have examined their neuropsychological correlates using quantitative MRI. Several studies reported no significant associations of hippocampal volumes and neuropsychological functions

(11–

13). In contrast, Goldberg et al.

(14) reported that in a group of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia, intrapair differences in left anterior hippocampal volumes correlated significantly with intrapair differences in logical memory but not other functions. Bilder et al.

(15) found that smaller anterior hippocampal volumes were associated with lower scores on measures of executive and motor functions considered sensitive to the integrity of the frontal lobes in patients experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia. This study was interpreted in the context of a neurodevelopmental defect within the medial frontolimbic system involving the anterior hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and/or dorsal aspects of the premotor or prefrontal cortex. The medial frontolimbic system or dorsal archicortical trend

(16) has been hypothesized to be important for redundancy-biased activation of cortical networks for executive functioning and forward planning; an abnormality in these brain structures and/or their connections may, at least in part, constitute the structural basis for frontal lobe dysfunction in schizophrenia

(15,

17–

20).

Several reviews

(21,

22) have highlighted important neuroanatomical and functional differences between posterior and anterior hippocampal entorhinal-hippocampal projections

(23). Specifically, the posterior hippocampus receives converging sensory input from posterior cortices, whereas the anterior hippocampus is connected primarily with the striatum and other parts of the limbic system. Empirical evidence for an anterior or posterior distinction of the hippocampus has been observed in functional MRI

(24) and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging

(25). In addition, in a meta-analysis of positron emission tomography (PET) studies of experimentally induced changes in blood flow

(26), episodic memory encoding was found to be associated with anterior hippocampal activations, whereas episodic memory retrieval was associated with posterior hippocampal activations. A subsequent report

(27), however, which included and excluded studies on the basis of criteria from the meta-analysis, reported that encoding activations in PET studies were observed frequently in both posterior and anterior mesiotemporal lobe regions. One possible reason for the apparent lack of a consistent relationship between hippocampal and neurocognitive measures in schizophrenia may be the lack of a distinction between the posterior and anterior hippocampus. Indeed, several studies that did distinguish between these regions implicated abnormalities in the anterior hippocampus compared to other parts of the hippocampus or other limbic structures

(15,

28–

31).

Results

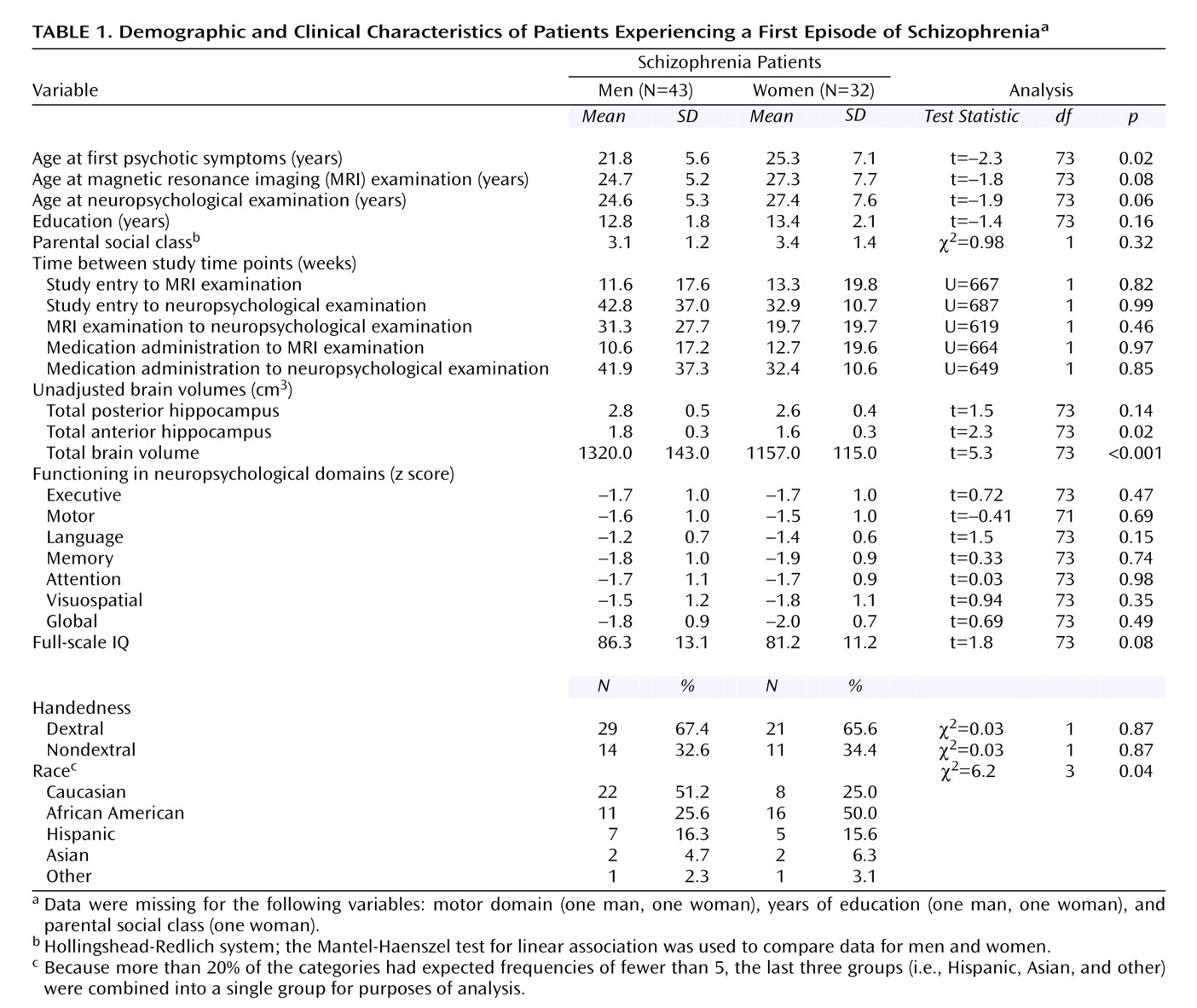

Group characteristics and the numbers of weeks between various time points in the study are reported in

Table 1. Male and female patients did not differ significantly at the time of the MRI or neuropsychological examinations in age, years of education, parental social class, handedness, or performance in any of the neuropsychological domains. In addition, there were no significant differences between male and female patients in the number of weeks between the various time points in the study (i.e., study entry, administration of antipsychotic medications, MRI examination, and neuropsychological examination). The groups did differ significantly, however, in age at onset of psychotic symptoms and in racial or ethnic composition (

Table 1). We also compared demographic variables for the 75 patients in this study and the 36 healthy comparison subjects who were used to standardize patient scores on the neuropsychological domains. Similar to our previous study

(42), the patient and healthy comparison groups were well matched on distributions of sex, age, and handedness (all p>0.05) but differed in parental social class (χ

2=6.2, df=1, p=0.01). Possible effects of this difference were investigated in subsequent analyses.

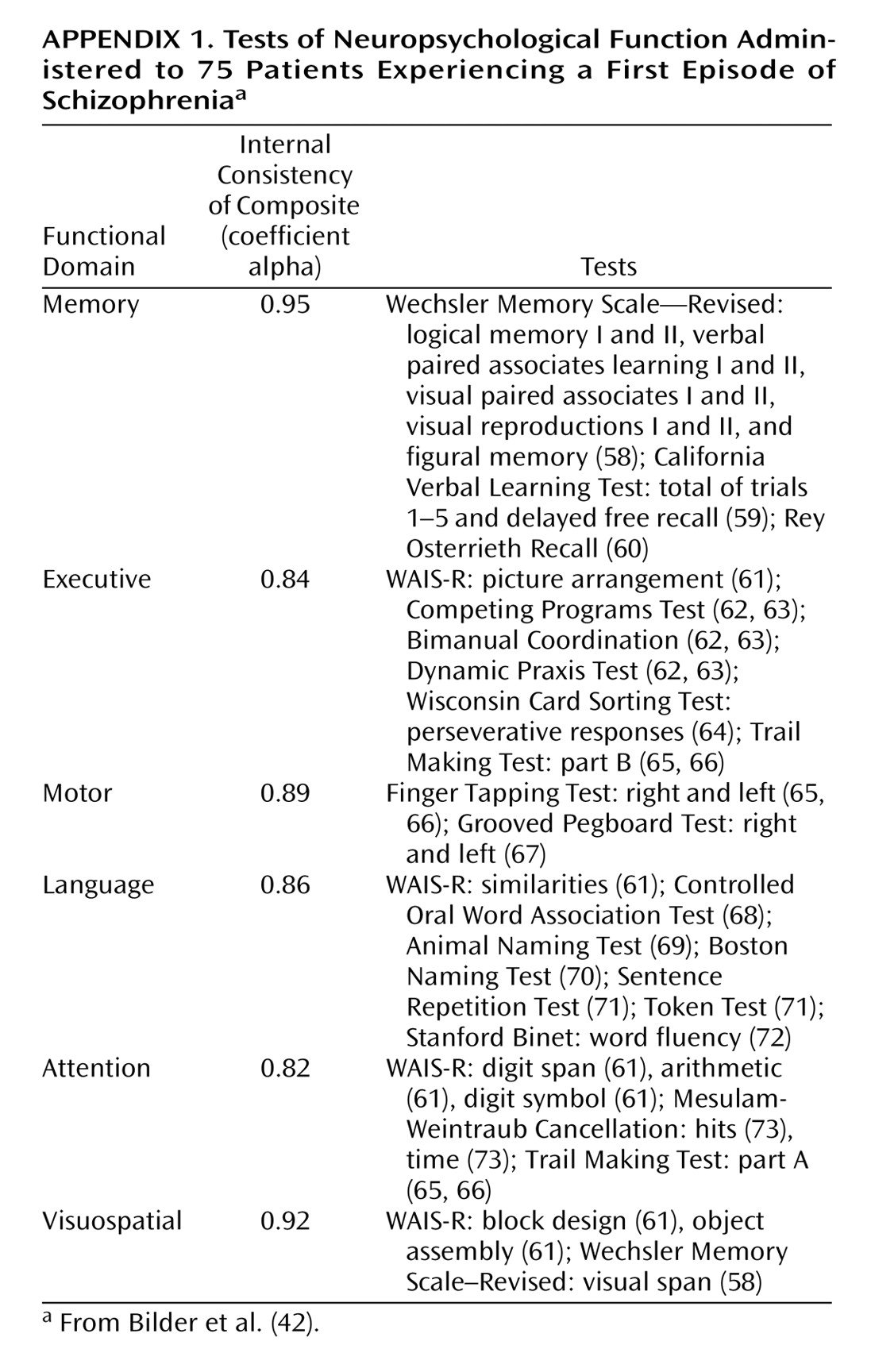

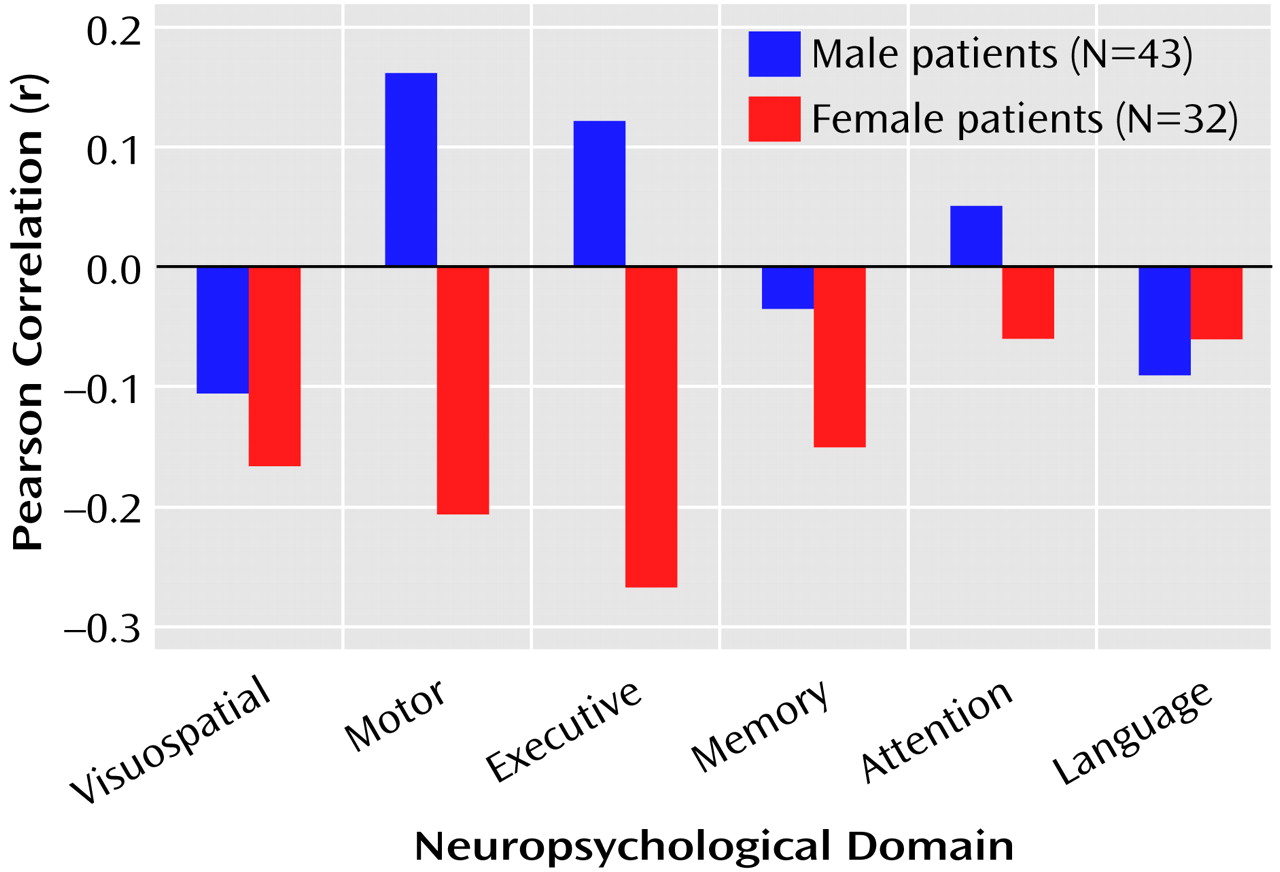

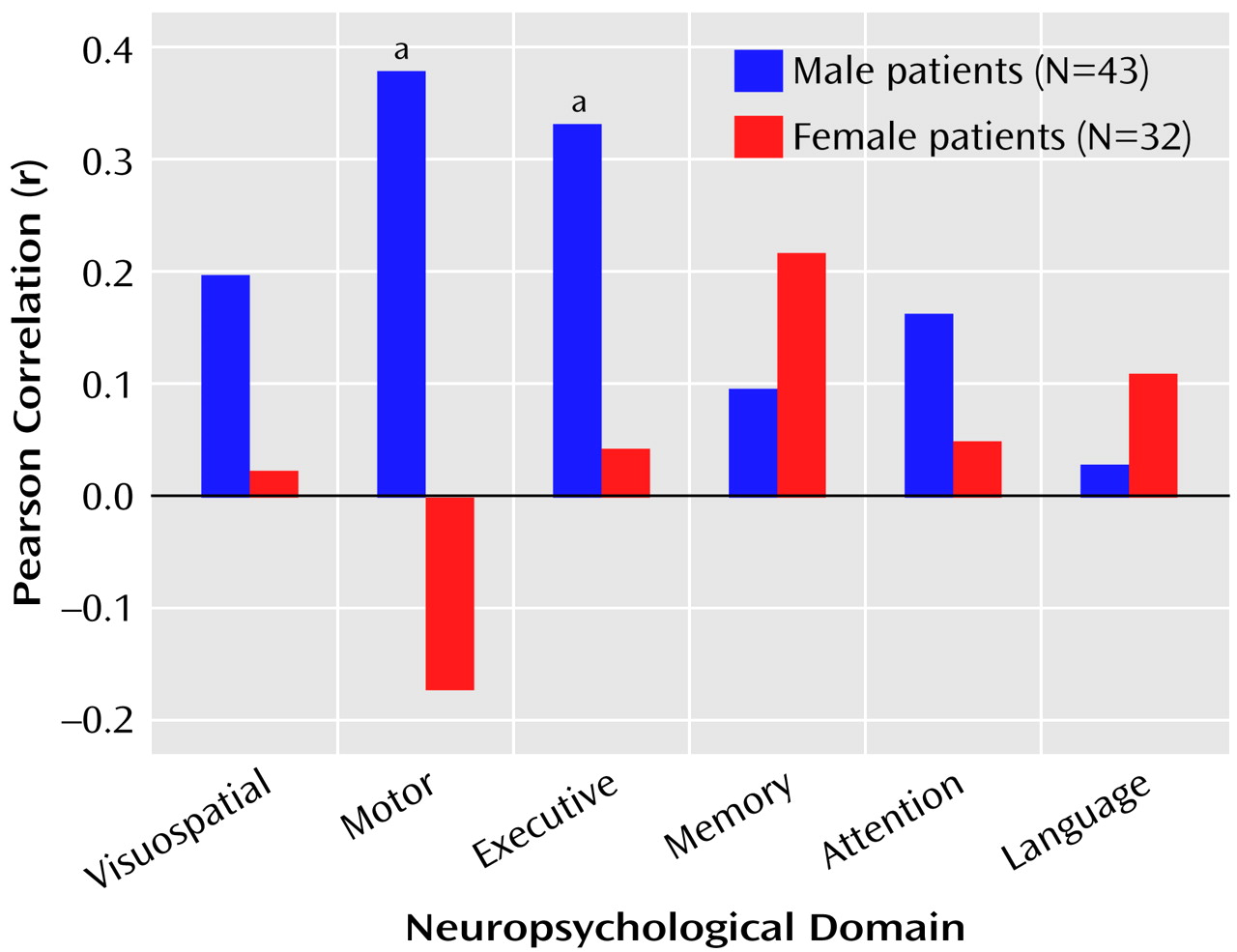

The correlations between total posterior and total anterior hippocampal volumes and the six neuropsychological domains are illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Figure 1 shows that posterior hippocampal volume was not significantly correlated with functioning on any of the neuropsychological domains among men or women with a first episode of schizophrenia (all p>0.05). Anterior hippocampal volume was significantly correlated only with executive (r=0.33, df=43, p=0.03) and motor (r=0.38, df=42, p=0.01) functioning among men; none of the correlations between anterior hippocampal volume and neuropsychological functioning was statistically significant among women with a first episode of schizophrenia (

Figure 2).

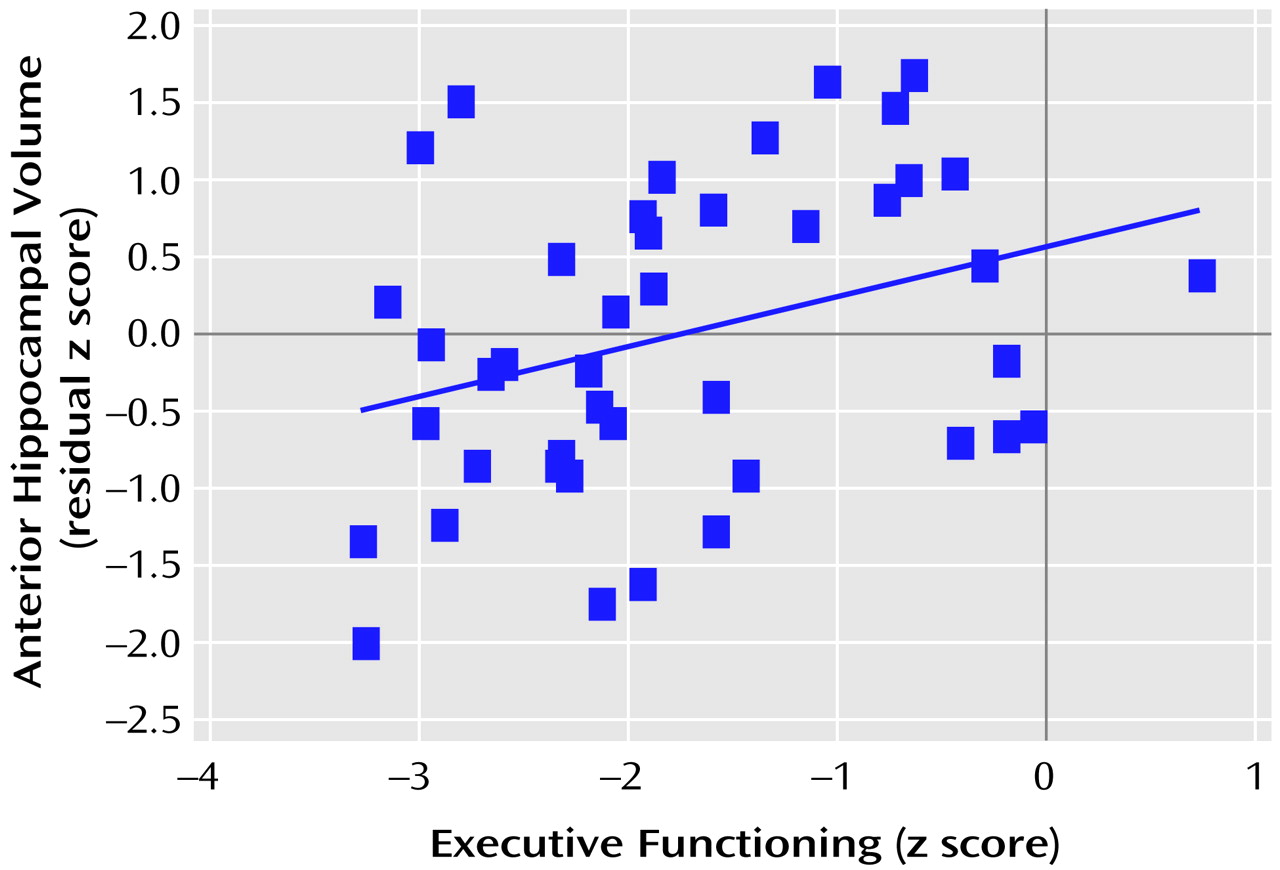

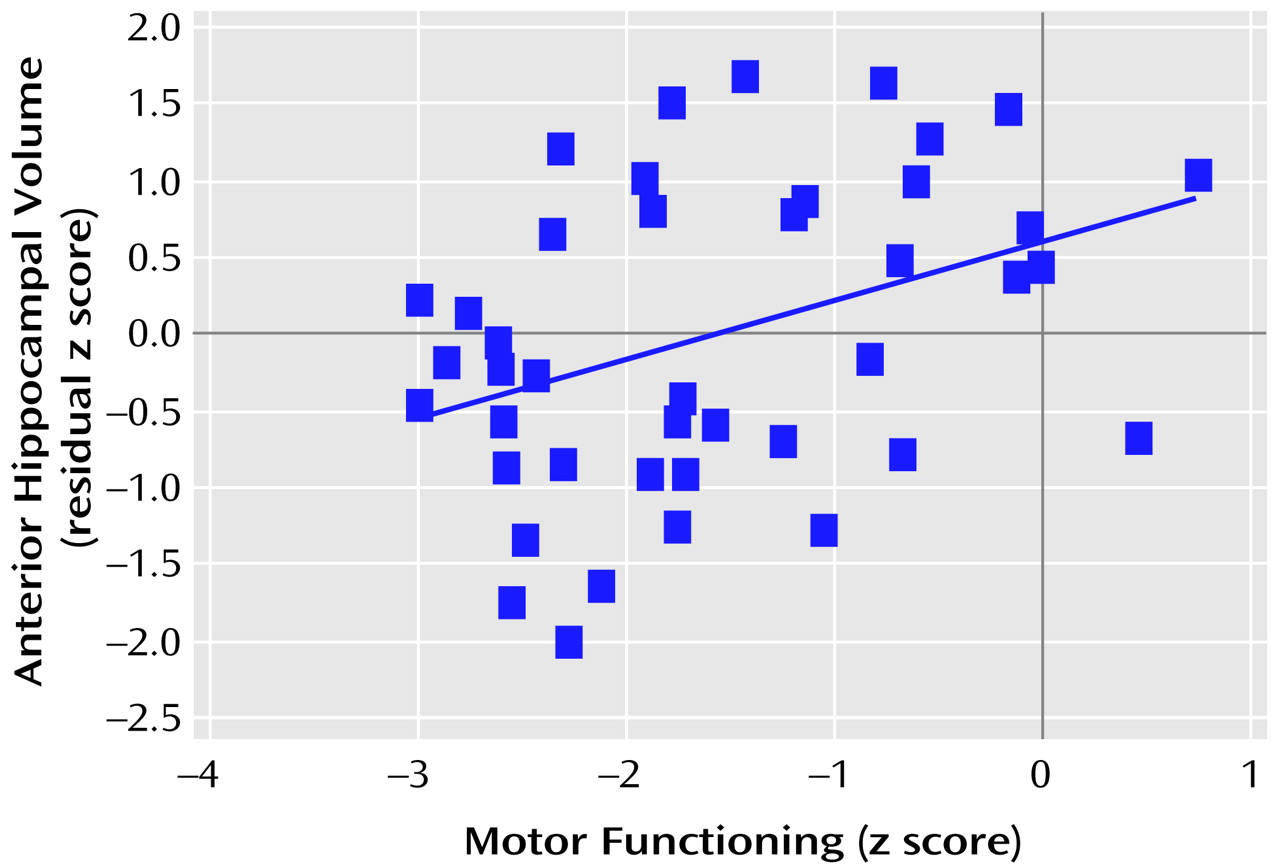

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 provide the scatter plots for the relation of anterior hypocampal volume to executive or to motor functioning among men with a first episode of schizophrenia. The use of Spearman’s rank-order correlations did not alter any of the significant (or nonsignificant) findings.

Additional analyses examined the possible effects of racial or ethnic group composition by comparing the coefficients of determination (r2) for the Caucasian subjects, the only racial or ethnic group that was large enough for analysis, and the entire group of male patients. The coefficients of determination for the correlations of anterior hippocampal volume and executive functioning and anterior hippocampal volume and motor functioning were comparable between groups. We also examined the possible effects of parental social class and age at onset (by using partial correlations) on the observed findings; these analyses did not differ substantively from the original analyses.

Tests of the difference between correlated correlation coefficients indicated that among the male patients (N=43), anterior hippocampal volume was significantly more strongly correlated with executive functioning than with either memory (difference: z=1.98, p=0.02) or language (difference: z=2.47, p=0.007) functioning. Similarly, among the male patients (N=42), anterior hippocampal volume was significantly more strongly correlated with motor functioning than with either memory (difference: z=2.03, p=0.02) or language (difference: z=2.11, p=0.02) functioning. Neither executive nor motor functioning was more strongly correlated with anterior hippocampal volume than with posterior hippocampal volume (p>0.05). Anterior hippocampal volume was more strongly correlated with motor functioning among male (N=42) than female (N=31) patients (difference: z=2.34, p=0.01).

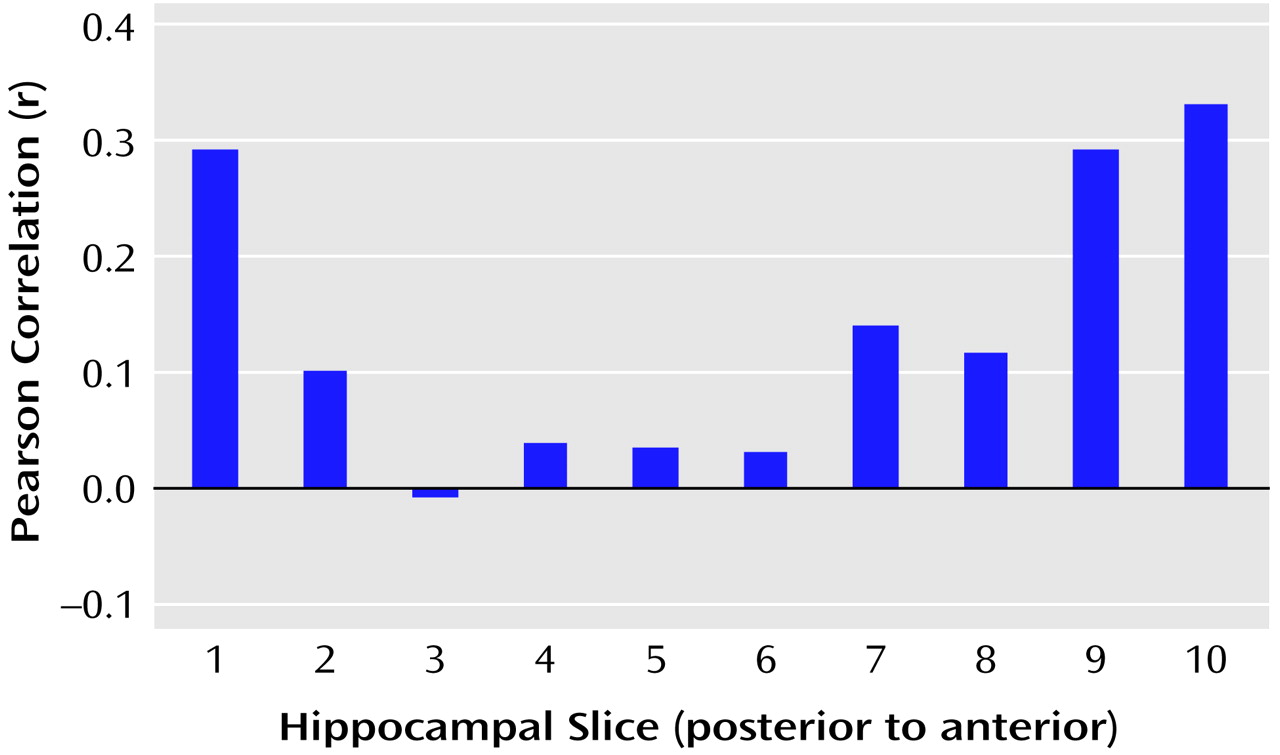

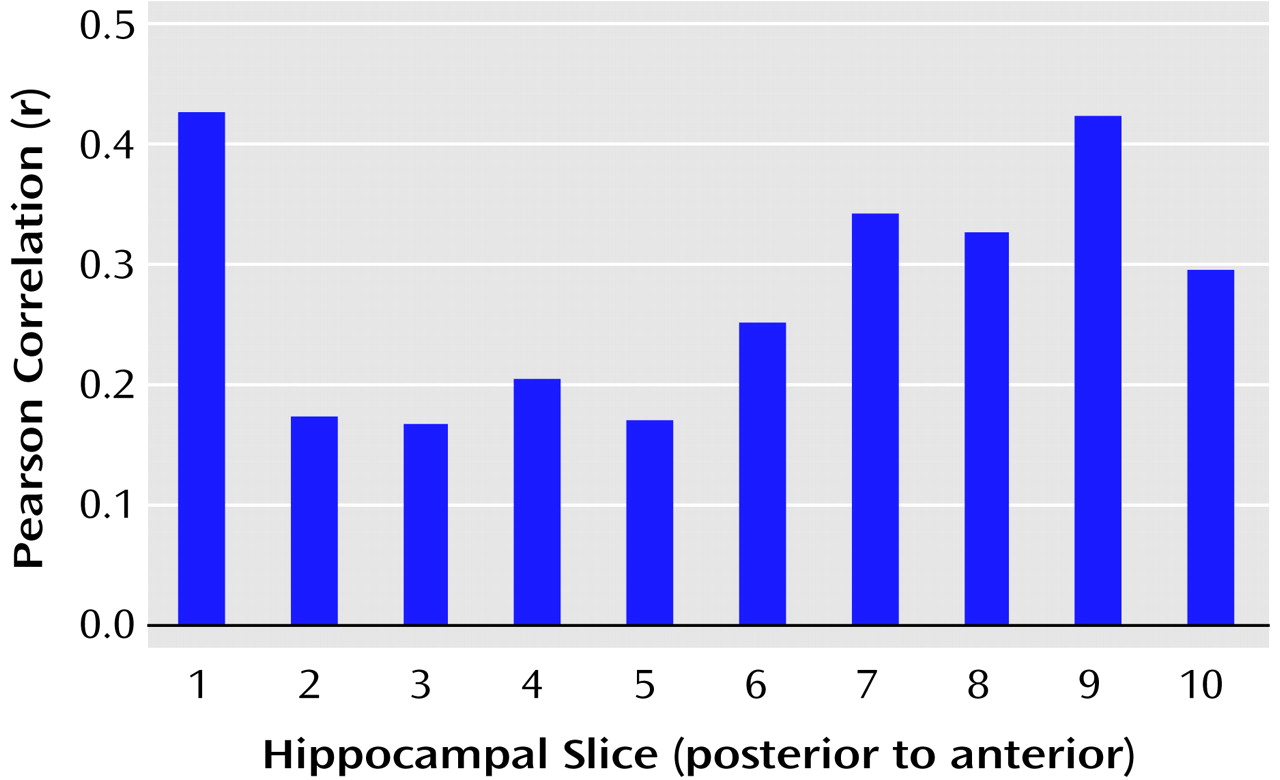

We tested the hypothesis that there would be a linear relationship between executive and motor performance and hippocampal volume across its long axis (after cubic-spline interpolation to 10 evenly spaced slice positions). The correlations between executive and motor functioning and volumes of individual hippocampal slices are illustrated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, respectively. Results of these analyses, however, indicated that when examined across its long axis, the relationships between hippocampal volume and executive performance (F=1.37, df=1, 8, p=0.28) and hippocampal volume and motor performance (F=1.05, df=1, 8, p=0.34) were not linear.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that anterior hippocampal volume correlates significantly with neuropsychological functions in male patients experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia who were studied soon after illness onset and before extensive pharmacological intervention. Among male patients, anterior hippocampal volume was more strongly correlated with both executive and motor functioning than with either memory or language functioning. These findings also suggest that the pattern of correlations between structure and function differ between male and female patients.

Despite evidence for hippocampal abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia, few MRI studies have investigated their neuropsychological correlates. In one such study, Hoff et al.

(11) reported no significant associations of hippocampal volume with neuropsychological measures in a sample of patients experiencing a first episode of schizophreniform illness. Similarly, DeLisi et al.

(12) and Nestor et al.

(13) reported no significant neuropsychological correlates of hippocampal volumes in their patient samples, although significant associations were identified with the parahippocampal gyrus. In contrast to these studies, Goldberg et al.

(14) implicated the left anterior hippocampus in the inability of patients to repeat stories read to them. Differences between our study findings and those of previous reports may be related to selection and diagnostic issues and methodological differences in measuring the hippocampus, including our distinction between the posterior and anterior hippocampus. In addition, if neuropsychological deficits are more strongly tied to anterior hippocampal abnormalities, studies investigating the entire hippocampus might not detect these associations.

The finding that smaller anterior hippocampal volume was associated with deficits in performance of executive and motor tasks considered sensitive to the integrity of frontal lobe functioning may seem paradoxical in light of research that has implicated the hippocampus in memory formation and consolidation

(46,

47). Moreover, we did not observe any significant correlation between hippocampal volume and memory functioning in patients. It should be noted, however, that although studies have identified memory deficits as the most conspicuous result of hippocampal lesions, such findings were often obtained following normal development in healthy humans after they sustained some focal lesion or in temporal lobe epilepsy. In schizophrenia, hippocampal abnormalities are more likely the result of some neurodevelopmental abnormality rather than the result of an acquired lesion, and therefore, the adult-lesion model may not be applicable

(48,

49). Animal studies have indicated that early developmental lesions to the hippocampal formation may not yield evidence of memory deficits; rather, these animals demonstrated both pharmacological and behavioral abnormalities that are more consistent with frontal lobe lesions in adult animals

(50–

53). Particularly noteworthy is that these animals with developmental lesions demonstrated evidence of “frontal dysfunction” only when they matured into adolescence or adulthood. Our results are therefore consistent with the hypothesis that some neurodevelopmental abnormality affecting the anterior hippocampus may later disrupt frontolimbic functioning in adulthood, thereby yielding a pattern of frontal lobe dysfunction. Thus, the adult-lesion model (with its implication that memory deficits are strongly tied to hippocampal integrity) may therefore be less relevant to our understanding of structure-function relations in schizophrenia, given that neurodevelopmental mechanisms are hypothesized to play a significant role in the pathophysiology of the disorder.

Given the extensive anatomic connections between frontal and mesiotemporal regions, a defect in connectivity between these regions may therefore be implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia

(17,

26). Csernansky et al.

(54) found that the superior and lateral aspects of the hippocampal head, which have strong connections with the medial prefrontal regions, had the greatest shape abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia. Similarly, Weinberger et al.

(55) found that differences in anterior hippocampal volume computed between monozygotic twins who were discordant for schizophrenia were significantly correlated with the difference between the twins in regional CSF to the prefrontal cortex during performance of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. It is therefore plausible that neurodevelopmental abnormalities in the medial frontolimbic system—which includes the dorsal aspects of the premotor and prefrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus, and anterior hippocampus—may comprise the structural basis for the observation of executive and motor dysfunction in schizophrenia. The medial frontolimbic system, in which the frontal lobes and the limbic system are linked by the cingulate bundle

(17), is isomorphic with the medial/dorsal archicortical system and can be distinguished from the ventral or lateral paleocortical system that comprises the olfactory cortex and the peri-insular and ventral neocortices, including the orbital frontal cortex

(16). The dorsal archicortical system has been hypothesized to be important for projectional control of behavior

(56), including the types of executive and motor functions that correlated significantly with anterior hippocampal volume in this study

(57).

The present study, conducted with large groups of men and women with a first episode of schizophrenia, suggested sex differences in the functional correlates of anterior hippocampal volumes. Specifically, anterior hippocampal volume was more strongly correlated with motor dysfunction in male than in female patients. It is important to acknowledge a possible selection bias, however, in that female patients who were functioning better overall may have dropped out of the study earlier than women who were not functioning as well and, therefore, did not complete the neuropsychological assessment

(41). It is difficult to compare our results with prior research because few studies have investigated sex differences in structure-function relations in patients with schizophrenia. In one such study, Flaum et al.

(34) found that full-scale IQ was uncorrelated with brain regions of interest for their entire group of patients with schizophrenia. When patients were divided by sex, however, female patients had a pattern of correlations similar to that observed in normal comparison subjects, while no such relationship was evident among the male patients. In another study, Szeszko et al.

(20) found that smaller anterior cingulate gyrus volume correlated significantly with worse executive functioning in male, but not female, patients experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia. Future research would benefit from the investigation of possible sex differences in analyses of structure-function relations in schizophrenia, as this may have implications for better understanding the pathophysiology of the disorder. For example, it may be that male patients have more pronounced abnormalities in the medial frontolimbic system, and this may be reflected in their neuropsychological test performance.

Although executive and motor functioning correlated significantly with anterior hippocampal volume and not with posterior hippocampal volume in the current study, these correlations were not statistically different from one another. This lack of anatomic specificity was most evident in the slice-by-slice analysis of hippocampal volumes in the male patients, which revealed that the relationship between executive and motor performance and hippocampal volume along its long axis did not fit a linear model. It was not possible to determine in this study, however, whether correlations involving the posterior hippocampal slices reflected morphologic abnormalities in the hippocampus or possibly in adjacent subcortical structures. Moreover, hippocampal tissue posterior to where the crus of the fornix is interrupted by the surrounding pulvinar was not included in the posterior hippocampal volume measurement, and consequently, we were unable to determine whether the most posterior part of the hippocampal formation would also show a similar pattern of correlations.

It is important to note several limitations of our hippocampal delineation methods that may have influenced the observed pattern of correlations. First, although we used the MRI scan that contained the mammillary bodies to assist in making the distinction between the posterior and anterior hippocampus before analysis, the use of this landmark to differentiate these regions is arguably somewhat arbitrary and may, therefore, have only approximated true functional differences between these regions. Second, because precise separation of the anterior hippocampus from the amygdala was not possible in these MRI scans, the anterior hippocampal volume measurement may have included the most caudal parts of the amygdala, thereby lowering the correlations of anterior hippocampal volume with the executive and motor domains.

In summary, this study indicated that there are neuropsychological correlates of hippocampal volumes in male patients experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia and that this relationship may not be linear along the long axis of the hippocampus. The results of the present study also suggest that our prior findings

(15) were confirmed in a larger group of patients, even after independent remeasurement of the hippocampal formation. Strengths of this study include the large groups of male and female patients who were studied soon after illness onset, our assessment with a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery, and the distinction between the posterior and anterior hippocampus. Future studies should employ more precise methods for separation of the anterior hippocampus from the amygdala to better elucidate the functional correlates of these brain structures.