Borrelia burgdorferi is transmitted mainly by tick bites. It is currently the most frequently recognized arthropod-borne infection of the CNS in Europe and the United States

(2,

3). Lyme disease, like neurosyphilis, has distinctive stages and a wide range of neurological manifestations. Its relationship to psychiatric illness has been suggested primarily by case studies

(4–

8). However, such reports cannot exclude the possibility of coincidental comorbidity. To our knowledge, there is only one epidemiologic survey of the prevalence of

Borrelia burgdorferi infection in a psychiatric population. Nadelman et al.

(9) found only one subject with antibodies to

Borrelia burgdorferi among 517 psychiatric patients from an area in the United States where the prevalence of antibodies to

Borrelia burgdorferi among the healthy population was less than 1%.

Results

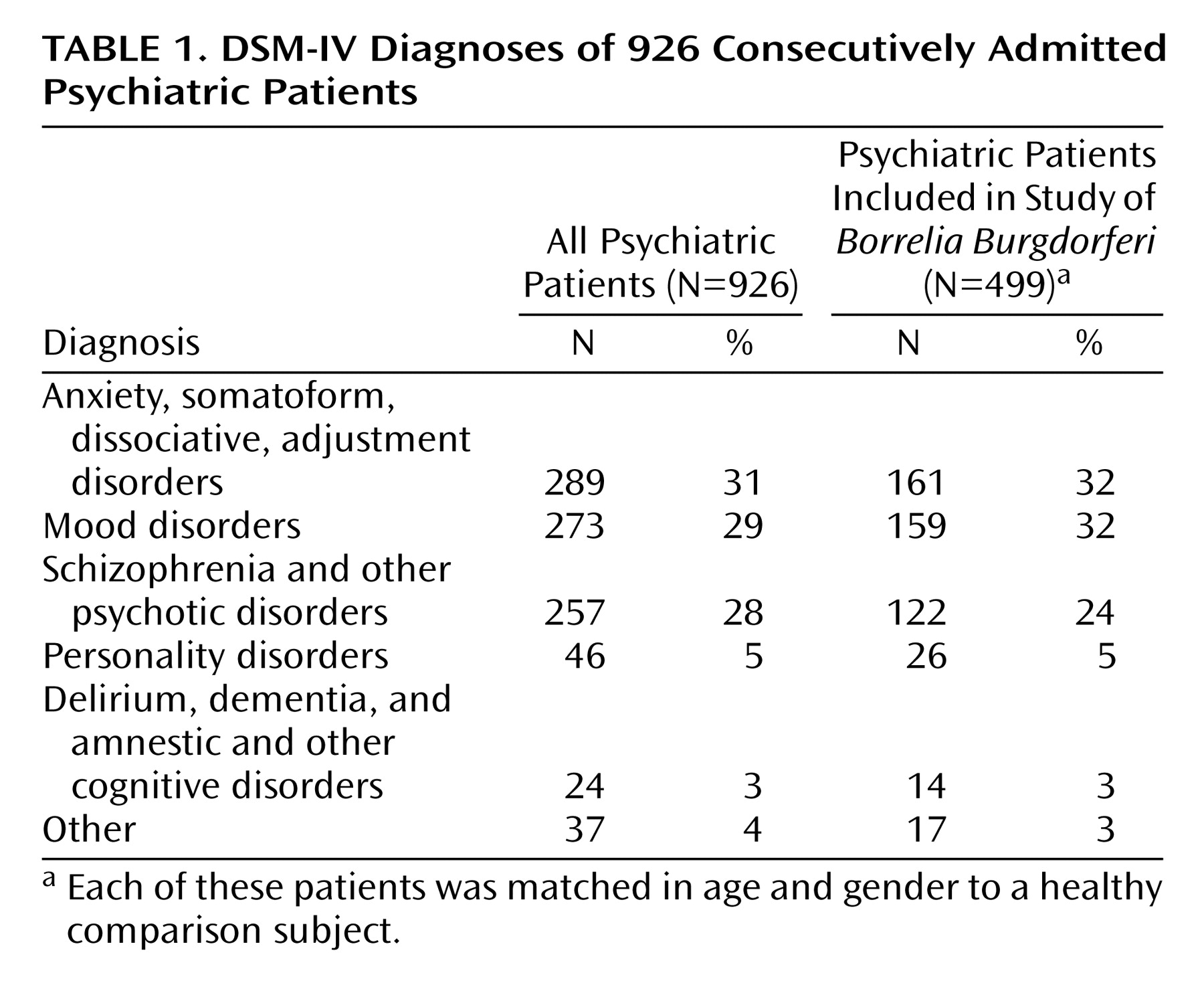

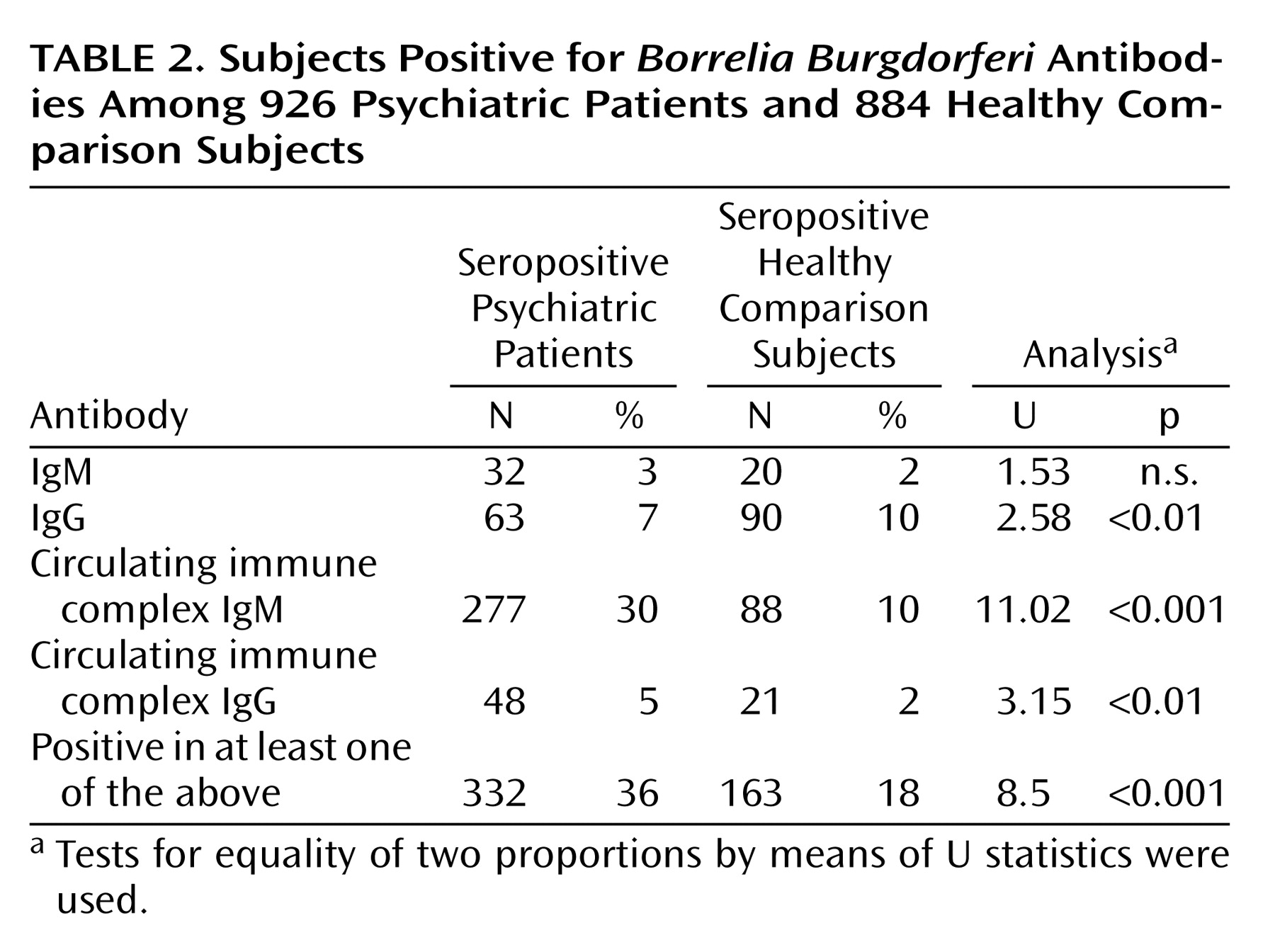

In the comparison of all patients and comparison subjects, 332 (36%) of 926 psychiatric patients and 163 (18%) of 884 comparison subjects were seropositive in at least one antibody class (

Table 2).

The mean age of the psychiatric patients was 36 years (SD=14, range=16–99), and 377 (41%) were men. The mean age of the healthy subjects was 27 years (SD=20, range=1–82), and 422 (48%) were men (t=–10.13, df=1808, p<0.001 for age and Yates-corrected χ2=8.77, df=1, p<0.01 for gender). Both age (t=–2.27, df=1808, p<0.05) and gender (Yates-corrected χ2=7.63, df=1, p<0.01) were associated with seropositivity.

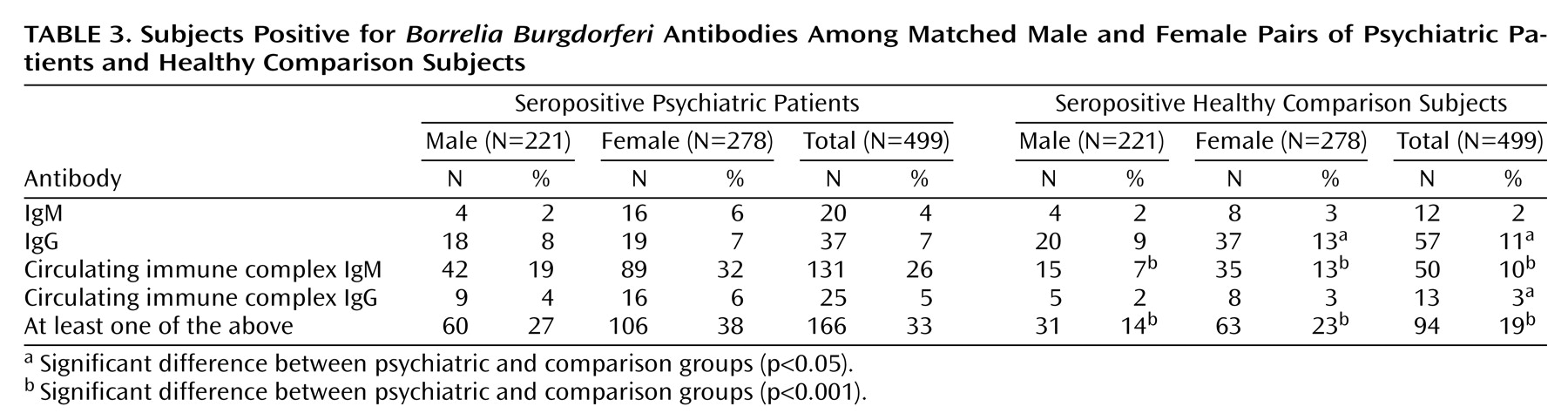

Matched groups consisted of 499 subjects each; 221 (44%) of the pairs were male. The mean age of the psychiatric patients was 36.2 years (SD=15.3, range=16–82), and the mean age of the comparison subjects was 36.1 (SD=15.3, range=16–82). Matching did not affect the proportion of subjects positive for each antibody type significantly and caused only a small reduction in the difference between the groups (

Table 3). Among the matched subjects, 166 (33%) of the psychiatric patients and 94 (19%) of the healthy subjects were positive in at least one antibody class (test for equality of two proportions, U=5.3, p<0.001, McNemar χ

2=25.21, df=1, p<0.001).

More women than men were seropositive in the comparison group (23% versus 14%) (U=2.52, p<0.001) and in the psychiatric patient group (38% versus 27%) (U=2.63, p<0.001). Seropositivity was more frequent in the psychiatric group in both women (U=4.02, p<0.001, McNemar χ

2=14.34, df=1, p<0.001) and men (U=3.46, p=0.001, McNemar χ

2=10.18, df=1, p<0.001) (total McNemar χ

2=25.21, df=1, p<0.001) (

Table 3).

There were no significant differences between the groups in number of IgM-positive subjects (women U=1.67, p=0.1, McNemar χ

2=2.04, df=1, p=0.15; men, U=0.000, p=1.0, McNemar χ

2=0.13, df=1, p=0.72; total, U=1.43, p=0.15, McNemar χ

2=1.53, df=1, p=0.22). There were more IgG-positive healthy women (U=2.55, p=0.01, McNemar χ

2=6.02, df=1, p=0.01) and more IgG-positive healthy subjects overall (U=2.17, p<0.05, McNemar χ

2=4.4, df=1, p<0.05) and no significant differences in IgG in men (U=0.34, p=0.73, McNemar χ

2=0.029, df=1, p=0.86). There were more circulating immune complex IgM-positive psychiatric patients (women, U=5.66, p<0.001, McNemar χ

2=27.01, df=1, p<0.001; men, U=3.9, p=0.0001, McNemar χ

2=13.26, df=1, p<0.001; total, U=6.8, p<0.001, McNemar χ

2=41.29, df=1, p<0.001). There were more circulating immune complex IgG-positive psychiatric patients overall (U=1.99, p=0.05, McNemar χ

2=3.18, df=1, p=0.07), although the differences were not significant for each gender separately (women, U=1.67, p=0.09, McNemar χ

2=2.04, df=1, p=0.15; men, U=1.09, p=0.28, McNemar χ

2=0.64, df=1, p=0.42) (

Table 3).

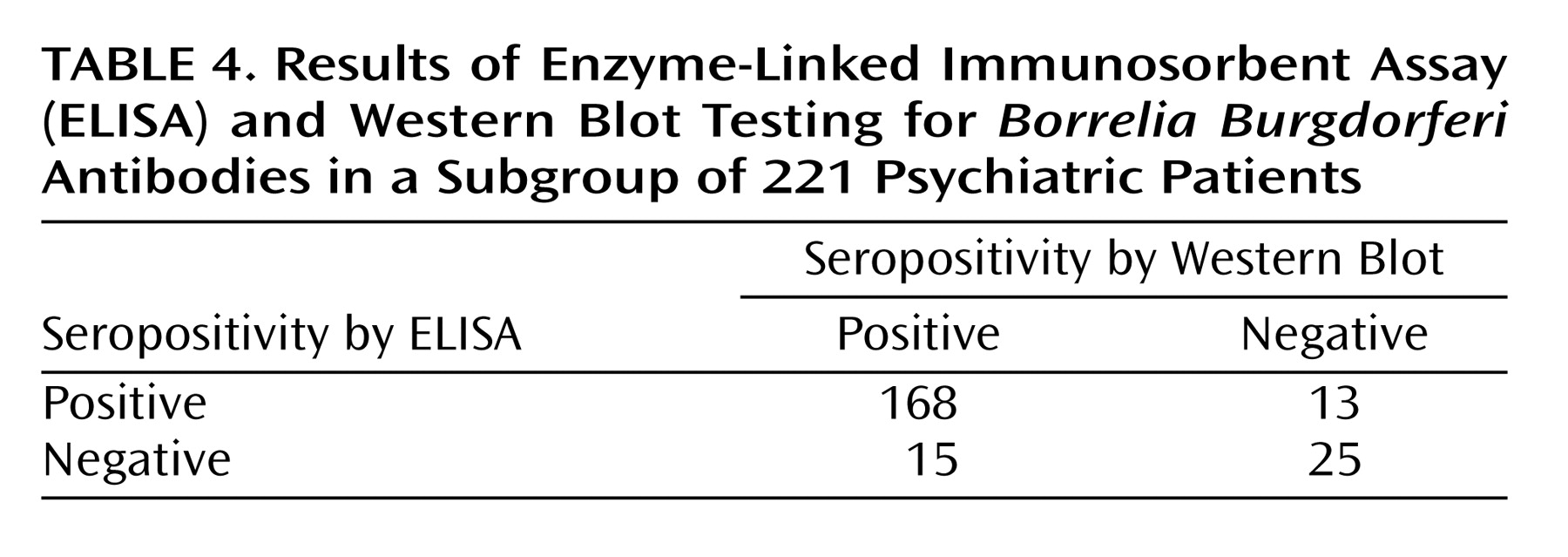

To verify the reliability of ELISA, samples from 221 psychiatric patients were examined by Western blot test. Agreement between the two tests was 87% overall, with 92% sensitivity and 66% specificity of ELISA as assessed by Western blot (

Table 4).

Discussion

One-third of the psychiatric patients had serological signs of past Borrelia burgdorferi infection. This rate is 1.7 times higher than the rate in matched comparison subjects.

Our results contrast with those of Nadelman et al.

(9), who reported only 0.2%

Borrelia burgdorferi seropositive subjects among psychiatric patients in a region of the United States where prevalence of

Borrelia burgdorferi is below 1%. The much higher prevalence of antibodies to

Borrelia burgdorferi in our study is typical for several areas of Europe

(16). The U.S. study used an older method (fluorescent immunoassay) in 90% of cases and ELISA in only 10%. It did not include antibodies bound in circulating immune complexes, where we found the highest number of positive cases. It is also possible that different genospecies of

Borrelia burgdorferi may be associated with different clinical manifestations

(17). In the United States,

Borrelia burgdorferi predominates, but in Europe,

Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia garinii, and

Borrelia afzelii are all detected.

We controlled for between-group differences in age and gender in the analysis. However, there are other potential confounding factors that need to be clarified and considered in future research. These include false positive results, reliability of the laboratory tests, hospitalization in psychiatric hospitals, and subjects’ lifestyles.

Sonicate ELISA IgM antibodies can show false positive results in patients with acute Epstein Barr virus, Varicella zoster virus, and cytomegalovirus infections owing to polyclonal B lymphocyte stimulation

(3). These infectious agents have been reported to be occasionally associated with psychiatric symptoms

(18). To influence the results of this study, the prevalence of these acute viral infections among psychiatric patients would have to be high and the acute illnesses would have to remain undetected. Also, patients exposed to

Treponema pallidum, or other spirochete infections (the prevalence of which is rather small in comparison to prevalence of Lyme borreliosis, let alone of

Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies), and patients suffering from rheumatic illnesses (systemic sclerosis or systemic lupus erythematosus) could show false positive results. It is unlikely that these patients would remain undiagnosed and treated in our clinic. To make sure that we were not dealing with false positive results, we used Western blot to test samples from a subgroup of 221 patients. In 93% the Western blot confirmed the ELISA positive results.

In regard to the reliability of the laboratory tests, samples from both groups were analyzed in the same laboratory, and the technicians performing the analyses were blind to sample allocation.

At least some patients might have encountered Borrelia burgdorferi in psychiatric hospitals, which are often situated in parks with mature trees and bushes. However, IgM antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi appear only days to weeks after the infection. In our patients, the blood samples for the serological assessment were taken immediately after their admission. There is still a possibility, however, that some patients might have been infected during previous stays in other psychiatric hospitals.

Psychiatric patients may differ from healthy subjects in variables related to lifestyle that could increase the risk of Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Exposure to ticks in the urban population is usually associated with outdoor activities. Such activities are not likely to be particularly more common in psychiatric patients. However, in rural areas, the lifestyle variables may be relevant. Also, some psychiatric patients could have experienced transient homeless situations that could have increased the risk of exposure to infection. This would affect only a small proportion of subjects and for only short periods of time, however. Homelessness is rare in the Czech Republic, and all the patients in this study had a permanent home address.

There are additional limitations to the generalizability of our data. The psychiatric group was recruited in an academic psychiatric facility, which admits patients with unclear symptoms. Psychopathology associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection may be atypical and thus found more often in this setting than in the general psychiatric population.

In one of the markers, IgG, there was a higher proportion of seropositive healthy women than of women with psychiatric illness. There is no obvious explanation of this finding. One can speculate that active outdoor leisure activities that raise the risk of infection may be less common among female psychiatric patients. However, the possibility cannot be excluded that this is a chance result. Future studies should revisit this issue.

The finding of a high rate of psychiatric patients who are positive for circulating immune complex IgM might suggest that circulating immune complexes are involved in the pathogenesis of psychiatric symptoms associated with Lyme disease. Comparisons of antibody profiles in different manifestations of Lyme disease (e.g., cardiological, rheumatic, neurological, etc.) are warranted.

It is difficult to make any conclusions from our data about how the course of Lyme disease is related to psychiatric symptoms. The first antibodies to be produced early in the infection are IgM, followed by IgG. IgM response peaks 4–6 weeks after the infection but may persist for month to years regardless of the activity of the disease. IgG response peaks 6 weeks after the infection and may also persist for years

(19–

23). Early after the infection or later in its course, the antibodies are not in excess of antigens and appear in circulating immune complexes only. Complexed antibodies are likely to signify disease activity

(24).

If Borrelia burgdorferi is related to psychiatric morbidity, at least two main mechanisms could be responsible. First, patients vulnerable to psychiatric disease may be also more susceptible to Borrelia burgdorferi infection or perhaps to its neurotoxic effects because of genetic or intrauterine factors. Second, Borrelia burgdorferi infection may cause psychiatric symptoms. If the latter, a question arises as to how the same infectious agent can cause different psychiatric disorders. In theory, symptoms may vary according to the location and type of Borrelia burgdorferi-related damage. Alternatively, the infection may lower the host’s resistance, and the symptoms may reflect patient’s specific vulnerability (diathesis).

One approach to clarifying the relationship between Borrelia burgdorferi and psychiatric morbidity would be to examine differences in psychiatric epidemiology across countries, regions, and possibly time periods with different rates of Borrelia burgdorferi. To our knowledge, no such studies exist. Future research should address this issue.

Overall, the most parsimonious explanation seems to be that Borrelia burgdorferi infection can cause psychiatric symptoms, leading to psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, and that perhaps about 10% of psychiatric inpatients may be suffering from neuropathogenic effects of Borrelia burgdorferi. The potential implications of this are considerable. However, this is the first study reporting such a finding, there exist some alternative explanations of our results, and replications are needed. More advanced methods such as polymerase chain reaction analysis will likely improve the accuracy of the diagnosis in the future. To contribute to the clarification of some of these issues, we are currently comparing seropositive and seronegative psychiatric patients with regard to diagnosis, length of hospitalization, family history, and other factors.