Prospective diagnostic criteria for the prodrome of the first episode of schizophrenic psychosis are intended to distinguish prodromal syndromes from psychosis and other clinical phenomena. Our group modified earlier criteria that identified patients with a 40% risk of becoming psychotic within 1 year

(1) to produce the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes

(2). Like the earlier criteria, the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes consist of three sets of criteria for prodromal features and a psychosis criteria set. The first three criteria sets identify patients as prodromal on the basis of attenuated positive symptoms, brief intermittent psychotic symptoms, or genetic risk plus functional deterioration; patients meeting one or more of the criteria sets for prodromal features but not the psychosis criteria are defined as prodromal. Two of the three criteria sets focus on positive symptoms because retrospective data

(3) suggest that positive symptoms begin later than negative symptoms in the prodromal phase and crescendo in the last year before onset. Modifications incorporated into the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes (e.g., referencing a new rating scale, requiring recent onset or change) were intended to increase the reliability of identification of positive symptoms and to improve identification of patients at imminent risk for schizophrenic psychosis.

To gather information needed to apply the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes, we developed the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes

(4). The goal of this project was to field test the reliability and predictive validity of the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes when based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes.

Method

The Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes is a semistructured diagnostic interview including five components: the 19-item Scale of Prodromal Symptoms

(4), a version of the Global Assessment of Functioning with well-defined anchor points, a DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder checklist, a family history of mental illness, and a checklist for the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes. The Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes is designed for use by experienced clinicians who have undergone specific training (to be described). It can be obtained from one of us (T.J.M.), and translation into several languages is under way.

Patients were drawn from 81 consecutive individuals who gave written informed consent and were given the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes from Jan. 23, 1998, through June 5, 2000. The patients had been referred to our prodromal research clinic because of a suspected prodromal syndrome. Of these 81, 18 patients who consented to videotaping of their interviews by Oct. 25, 1999, and for whom two or more independent raters were available constituted the study group for the reliability study; their mean age was 19.6 years (SD=7.8), and 11 (61%) were male. For the validity study, 35 of the 81 patients were ineligible; 29 entered a still-blinded clinical trial, four met the criteria for psychosis, and two were missing baseline data. Of the remaining 46, 29 (63%) participated in follow-up and constituted the study group for the validity study; their mean age was 17.8 years (SD=6.1), and 19 (66%) were male. Of these 29, 13 met the criteria for prodromal syndrome at baseline, and 16 did not meet the criteria for either psychosis or prodromal syndrome. Of the 17 nonparticipants in the validity study, seven could not be located, nine refused to participate, and one was deceased. The mean age for these nonparticipants was 19.1 years (SD=6.3), 12 (71%) were male, and five (29%) had prodromal syndromes; there were no significant differences between this group and the participants.

In the reliability study, the original interview served as one rating for 16 of the 18 patients with complete data. All other ratings were made from videotapes. For each subject, the raters (between two and four of the six potential raters) were blind to all other ratings for that subject although aware of the reason for referral. There were 58 ratings total, 3.2 ratings per subject, and 70 pairs of ratings. Kappa was computed as the reliability measure

(5).

In the predictive validity study, the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes was conducted again at 6 and 12 months after baseline, and medication histories were reassessed. Most interviews were conducted face to face, but the interviews for four patients were conducted over the telephone. At follow-up, patients initially categorized as prodromal were diagnosed as still prodromal unless they had developed psychosis or had remitted. The criteria for remission included the absence of any positive symptom item in the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms with a score in the prodromal range. The association between initial diagnostic status and diagnostic outcome at follow-up was evaluated with two-sided Fisher’s exact tests. Exact confidence intervals (CIs) for outcome rates used the binomial distribution.

The interviewers were trained in use of the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes through an apprenticeship model. Each interviewer must have previously co-rated four to five patients with one of the interview’s developers and be judged by the developer as competent to administer the interview independently. A total of six interviewers participated as raters in the reliability study: one psychiatrist, one psychologist, three psychology postdoctoral fellows, and one research associate with extensive clinical experience (T.H.M., T.J.M., J.L.R., L.S., K.S., and P.J.M., respectively). In the validity study, the interviews were conducted by psychology postdoctoral fellows (J.L.R., L.S.).

Results

Of the 18 subjects in the reliability study, seven were categorized as prodromal by the interviewer diagnoses and 11 were categorized as nonprodromal (two were judged to already have schizophrenic psychosis, and nine were neither prodromal nor psychotic). All seven of the patients with prodromal features met the criteria for attenuated positive symptoms, either alone (N=6) or in combination with genetic risk plus functional deterioration (N=1). The agreement among raters was 93% for the judgment of whether the subjects were prodromal or nonprodromal (kappa=0.81, 95% CI=0.55–0.93).

In the validity study, 12 of the 13 initially prodromal patients met only the criteria for attenuated positive symptoms, and one met only the criteria for brief intermittent psychosis.

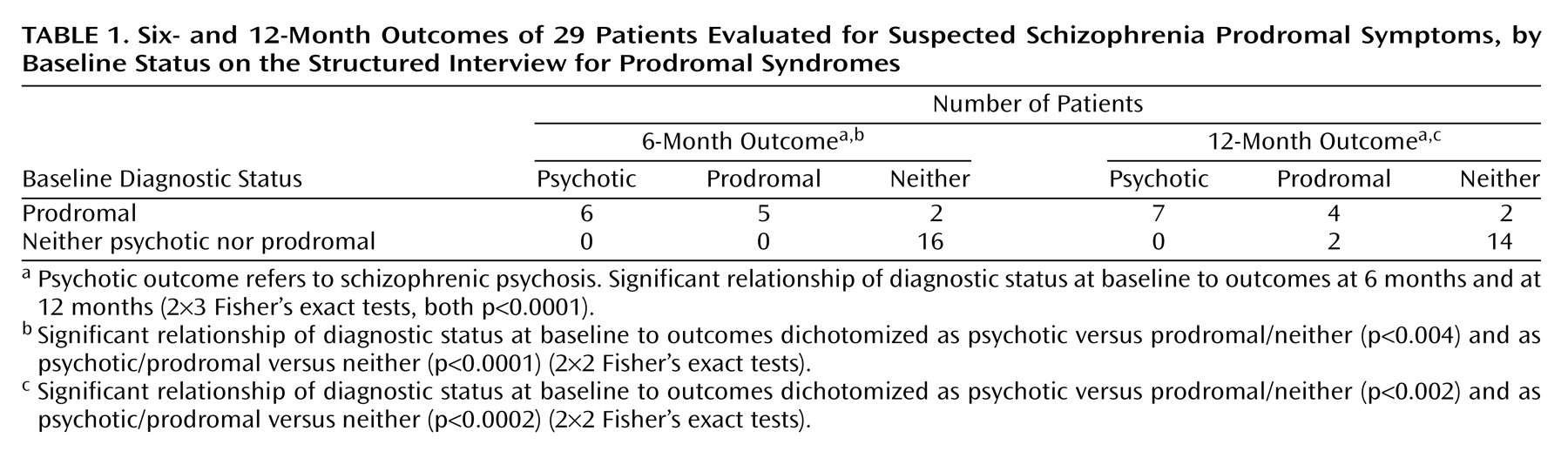

Table 1 shows that six (46%) of the 13 developed schizophrenic psychosis by 6 months, and the rate was 54% at 12 months. Initial diagnostic status was significantly associated with diagnostic outcome (

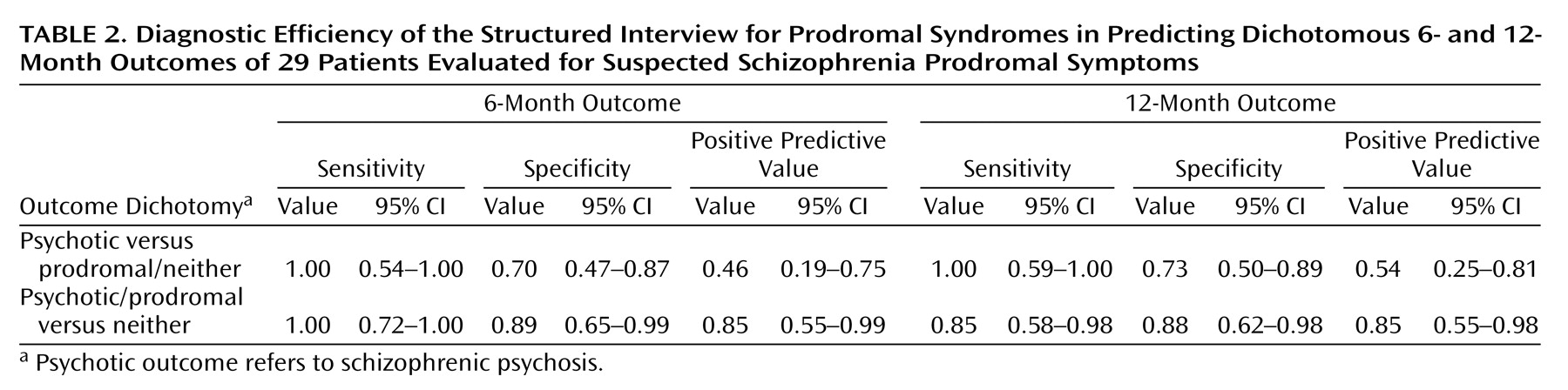

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Further evidence that the patients who did not develop schizophrenic psychosis were correctly diagnosed is that none received antipsychotic medication. Two patients’ prodromal symptoms remitted. No initially nonprodromal patient developed schizophrenic psychosis, but two met the criteria for prodromal syndrome 12 months later.

Discussion

The reliability data suggest that raters can use the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes to apply the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes in making diagnostic judgments regarding the presence of the prodrome for schizophrenia; the interview has excellent interrater reliability with patients who meet the criteria for attenuated positive symptoms. Reliability was achieved with patients relevant to the intended use of the instrument: those referred because of suspected prodromal syndrome. Caution is indicated because of the small study group. In addition, these results were achieved among a small group of raters at one site who had trained and worked together intensively with this diagnostic group. Future studies are needed to determine whether these results can generalize.

The significant association between initial diagnoses and outcomes based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes strongly supports the predictive validity of the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes for patients meeting criteria for attenuated positive symptoms. The rate of conversion from prodrome to schizophrenic psychosis in the present study is similar to that observed with the earlier criteria

(1). Longer follow-up is needed to determine whether patients with false positive diagnoses (either remaining prodromal or remitting) continue to be at risk for conversion. The Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes can also result in false negative diagnoses. This result is not surprising, since the present criteria are not intended to detect all prodromal patients but, rather, prodromal patients at relatively imminent risk of conversion to schizophrenic psychosis. Patients with subthreshold symptoms are invited to return for a repeat interview if their symptoms worsen.

The validity data must also be interpreted with caution. The study group was small, some eligible patients did not participate in follow-up, and the interviewers who made the follow-up diagnoses were not blind to the initial diagnoses. Another limitation is that the participants were primarily patients who met the criteria for attenuated positive symptoms. Future studies with larger study groups should investigate predictive validity in patients meeting the criteria for brief intermittent psychotic symptoms and for genetic risk plus functional deterioration. Other data relevant to validity, including the course of symptoms among patients remaining prodromal, the occurrence of other DSM-IV axis I and axis II disorders, and concordance of measures from other domains of measurement, such as cognitive functioning, remain to be analyzed.

Despite the preceding caveats, these initial reliability and validity results support the use of the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes and the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes in additional studies with patients suspected of having prodromal changes.