The prevalence of depression increases during adolescence and peaks in early adulthood

(1). Adolescent depression is related to early adulthood depression

(1–

3), higher occurrence of hospitalizations

(2), social adjustment and interpersonal problems

(2,

3), suicidality

(2,

3), and dissatisfaction with life

(3).

Previous studies have also shown evidence of the continuity of adolescent mood disorders

(1,

4). Therefore, finding easy-to-use measures to identify those at risk would be valuable. As part of a larger follow-up investigation on mental health risk factors among Finnish high school students, we examined whether adolescents’ self-reported depressive symptoms—as measured by a two-item query—predicted depressive and other psychiatric disorders in early adulthood.

Method

The study group and procedure have been described in detail

(6). In 1990, a questionnaire that assessed psychosocial well-being was delivered to 1,518 adolescent high school students from two Finnish cities who were attending their final three grades. Of these adolescents, 1,493 responded (mean age=16.8 years); 709 (47.5%) of the 1,493 respondents provided written, informed consent to be contacted for follow-up. No statistically significant differences between respondents consenting and those not consenting to be recontacted were found in age, family social class, or psychosocial variables measured at baseline

(6). Assessment of family social class followed the City of Helsinki social group classification and was based on the father’s occupation or on the mother’s occupation in cases where the father was not living in the family of the adolescent.

In 1995, 706 of the consenting subjects (mean age=21.8 years) were mailed a follow-up questionnaire. Of the 442 female subjects, 418 (94.6%) responded; of the 264 male subjects, 233 (88.3%) responded.

The main measure for screening psychiatric symptoms was the 36-item version of the General Health Questionnaire

(7), a widely used self-administered rating scale for screening psychiatric disturbance in individuals of the general population. The General Health Questionnaire inquires about the occurrence of various psychological symptoms during the previous month. Scores of 3 and 4 on a 4-point scale indicate the presence of a symptom. The presence of five or more symptoms in total out of 36 indicates psychiatric disturbance

(7). Of the 651 questionnaire respondents, 151 female and 52 male subjects scored above this cutoff point and were thus candidates for diagnostic interview. An additional 89 subjects (66 women and 23 men) were considered eligible for diagnostic interview on the basis of their responses to questions regarding lifetime referrals to mental health services, pathological eating behavior, high yearly intake of alcohol, or recurrent depressive feelings

(6). Thus in total, 292 persons were considered eligible for diagnostic interviews (the “screening positive” subgroup). In addition, 111 randomly selected subjects with no self-reported psychopathology (the “screening negative” subgroup) were asked to undergo the diagnostic interviews. Of all eligible or invited, 245 subjects (172 women and 73 men) completed the diagnostic interviews

(6). The interviewed and noninterviewed subjects did not significantly differ in terms of their General Health Questionnaire scores, family social class, age, or sex

(6).

Depressive symptoms in adolescence were assessed by two items in the 1990 questionnaire (“I often get depressed,” “I am continuously depressed”) rated on a 4-point scale in which 1=no, 2=somewhat, 3=moderately so, and 4=very much so. In order to exclude subjects with transient depressive feelings, this measure was dichotomized so that presence of depressive symptoms was recorded only for scores of 3 or 4 on either question or both.

Measurement of psychiatric disturbance refers to a total score of 5 or more on the 36-item General Health Questionnaire

(7). Problem drinking was defined as two or more positive answers on the four-item CAGE questionnaire

(8), designed to detect alcohol problems (subject has been asked to cut down drinking, been annoyed by criticism of his or her drinking, felt guilty about drinking, or ever resorted to drinking as an “eye-opener”).

Diagnostic interview data on the 245 subjects were collected by using the semistructured Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry

(9), which cover the major psychiatric disorders of adult life. Preliminary DSM-IV axis I research diagnoses, based on the DSM-IV hierarchy rules, were first set by the two interviewers by consensus and thereafter reconsidered with the consultant

(6). When needed, additional data based on the longitudinal expert all data standard

(10) were used to maximize the validity of the research diagnoses. Only current disorders occurring during the past 4 weeks were considered in the present study. We used a similar procedure to assess current level of psychosocial functioning according to the DSM-IV Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. On a scale of 0–100, subjects with Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores of 60 or less were considered impaired

(6).

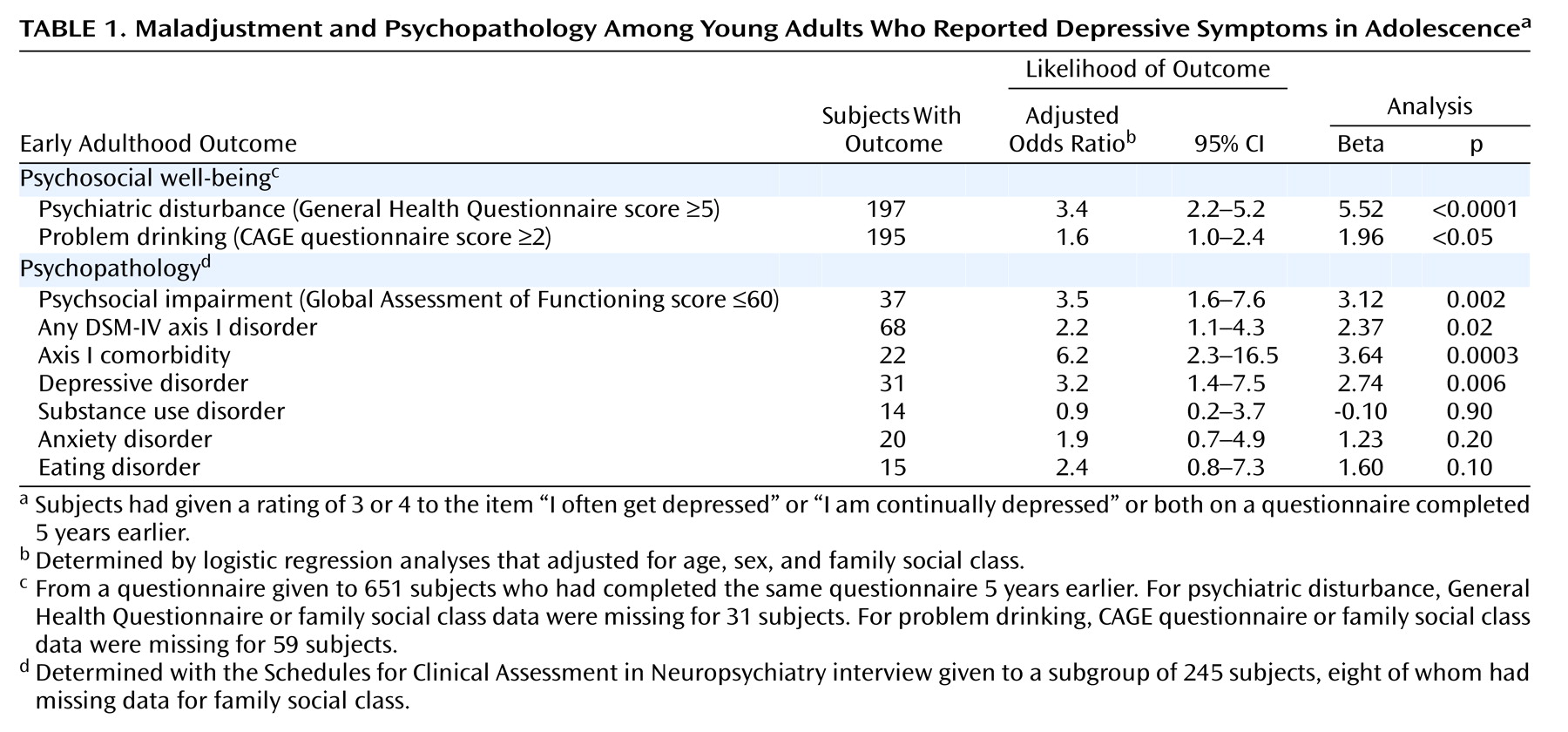

Adolescent depressive symptoms were analyzed against outcome data from questionnaire and interviews. We used logistic regression analyses to produce odds ratios for measuring the strength of associations between adolescent depressive symptoms and each early adulthood outcome. Age of respondent, family social class at baseline, and sex were used as covariates in each logistic model.

Discussion

Adolescent depressive symptoms predicted a high risk of depression, psychiatric comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment in young adulthood. Symptoms of depression in adolescence also predicted subsequent psychiatric disturbance and problem drinking.

Lack of diagnostic data at baseline precluded controlling for the presence of depressive disorders at that time. Furthermore, we are aware that besides depressive symptoms, a range of other factors are probably associated with greater risk of the reported outcomes.

We consider the strengths of the present study to include the homogeneity of the study group of adolescent high school students, the follow-up design, and the careful diagnostic procedure.

Our results agree with prior findings

(4,

5) in showing the important predictive impact of adolescent depressive symptoms on subsequent depressive disorders, psychosocial impairment, and problem drinking. Our findings suggest that even a two-item measure may identify adolescents at greater risk of subsequent depression and maladjustment. Subclinical depressive symptoms in adolescence, not merely clinical depression, should be a focus of further research and clinical interest.