In any clinical trial, the validity of the study conclusion is limited by the reliability of the outcome measured

(1). Because of the subjective nature of the outcomes, the reliability of the outcome measures is particularly important in treatment trials of depressive disorders. Reliability usually refers to internal consistency, test-retest reliability, interrater reliability, and rater drift. Internal consistency and test-retest reliability are psychometric properties of the instrument. Interrater reliability refers to the consistency with which the same information is rated by different raters. Rater drift refers to the lack of consistency within a single rater over time. For continuous measures, such as clinical rating scales, interrater reliability can be estimated by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)

(2,

3). The ICC indicates how much of the variance in scores is due to “true” differences in what is actually measured versus differences in the way it is measured. In general, ICCs are higher if a large number of patients is rated and the patient population rated reflects the full range of the phenomenon being measured

(2,

4). When provided with an ICC, a clinician can interpret the meaning of the difference between scores obtained by different raters assessing different patients separately. For instance, if interrater reliability has been established for two raters and an ICC of 0.60 has been calculated, a 5-point difference in score obtained by these two raters can be interpreted as follows: 60% (3 points) of the difference between the two scores is due to a “true” difference between the two patients’ symptoms, and 40% (2 points) is due to differences in the way they were rated.

The practical importance of interrater reliability is dramatically illustrated by an analysis of the outcome differences among 29 clinical sites involved in a multisite, double-blind antidepressant trial for geriatric depression

(5). In this original study, 671 older outpatients who met diagnostic criteria for major depression were randomly assigned to treatment with an active antidepressant (fluoxetine) or placebo. Patients were evaluated at baseline and at completion of the trial with the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(6). A single training session was held before the study began, and no measure of interrater reliability was obtained. Site-specific effect sizes ranged from 1.84 (favoring fluoxetine) to –0.91 (favoring placebo). Despite the large number of subjects in this trial, no significant difference in Hamilton depression scale mean change scores between fluoxetine and placebo was observed. The authors hypothesized that the large variability in response may have been due to a variety of factors. Most notably, they said

lack of interrater reliability may have contributed to site variability. Because the methods used in this trial are typical of the current standard for industry-sponsored trials, these results support the need for greater attention to methodological issues of multi-site clinical trials.

Thus, the results of a large and costly clinical trial could not be interpreted, possibly because of inadequate training of raters and the absence of a measure of interrater reliability. If interrater reliability had been demonstrated (e.g., by high ICCs), the observed variability across sites may have been more meaningfully interpreted. These potential problems associated with rater training and assessment of interrater reliability are not unique to this trial and may explain why some trials that appear to be adequately powered, on the basis of a dependable estimation of the expected effect size, end up being underpowered

(4).

Given the importance of adequate rater training and of establishing interrater reliability, we undertook a review to determine if and how these issues were being addressed in all original reports describing prospective, randomized, clinical trials of treatments for depressive disorders published in two high-impact psychiatric journals.

Method

The American Journal of Psychiatry and the Archives of General Psychiatry were selected because they have rigorous methodological standards and manuscripts undergo statistical review before being accepted for publication. We reviewed all original manuscripts published from 1996 to 2000 in the Journal and Archives. Two academic psychiatrists (B.H.M. and J.R.) independently reviewed the tables of contents of the two journals for these five years and identified 84 original reports of clinical trials of treatments for depressive disorders.

The reports were systematically reviewed to summarize the following: 1) number of centers involved in the study, 2) duration of the intervention, 3) method of rater training, 4) number of raters, 5) assessment of interrater reliability, 6) study enrollment duration, and 7) assessment of rater drift. When a Method section cited a previous publication, this publication was also reviewed. The list of the original reports reviewed is available on request.

Results

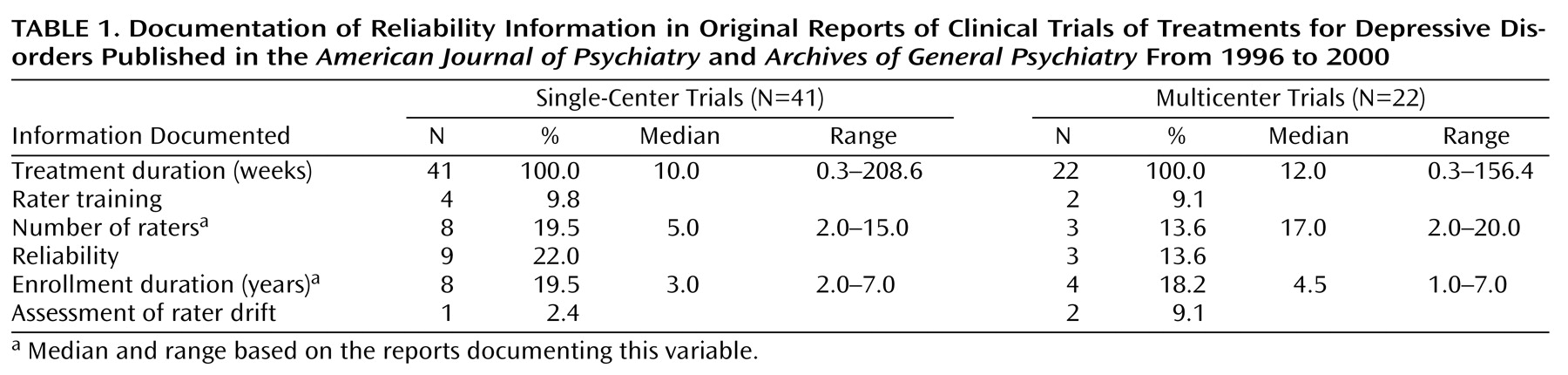

Of the 84 identified reports, 21 were excluded for the following reasons: 12 gave additional results for other included reports, four involved only one rater, and five did not involve outcome ratings. Of the 63 remaining trials, the median treatment duration in 41 single-center trials was 10 weeks; the median treatment duration in 22 multicenter trials was 12 weeks (

Table 1).

Rater training in scale administration was documented for four (10%) of the single-center trials and two (9%) of the multicenter trials. The number of raters was reported in eight (20%) single-center trials and three (14%) multicenter trials. The reported median number of raters was five for single-center trials and 17 for multicenter trials. Reliability was reported in nine (22%) single-center trials and three (14%) multicenter trials. Four (44%) of the nine single-center trials and none of the multicenter trials documenting interrater reliability reported the number of raters.

The median duration of study enrollment was 3 years in the eight single-center reports documenting enrollment duration; the median was 4.5 years in the four multicenter reports. Only one (2%) single-center and two (9%) multicenter trials documented assessment of rater drift. None of the eight single-center studies reporting duration of study enrollment provided a description of rater training or documented the assessment of rater drift. Only one of these studies reported interrater reliability, and only two reported the number of raters. None of the four multicenter studies documenting duration of study enrollment reported the number of raters, provided a description of training, or documented the assessment of rater drift. Only one of these four studies reported interrater reliability. Overall, none of the 63 trials reported all of the variables relevant to training and reliability.

Discussion

In this 5-year survey of the reports of clinical trials of the treatment of depressive disorders published in the American Journal of Psychiatry and Archives of General Psychiatry, less than 20% stated the number of raters and less than 10% described how raters were trained. Despite a reported median number of five raters, only 13% reported a measure of interrater reliability. Similarly, although the median duration of study enrollment was 3 years, less than 5% of the 63 papers addressed rater drift.

These findings suggest that interrater reliability in clinical trials of depressive disorders is not routinely documented despite being explicitly addressed as one of the criteria in peer review. We could not determine whether interrater reliability was not assessed or whether it was not reported in the clinical study. We advocate that instructions for authors suggest reporting length of study enrollment, number of raters, the training these raters received, and how interrater reliability was assessed. In addition, rater drift should be assessed and documented when appropriate.