Relationship of Mortality With Background and Impairment Variables and Comorbid Physical Illness

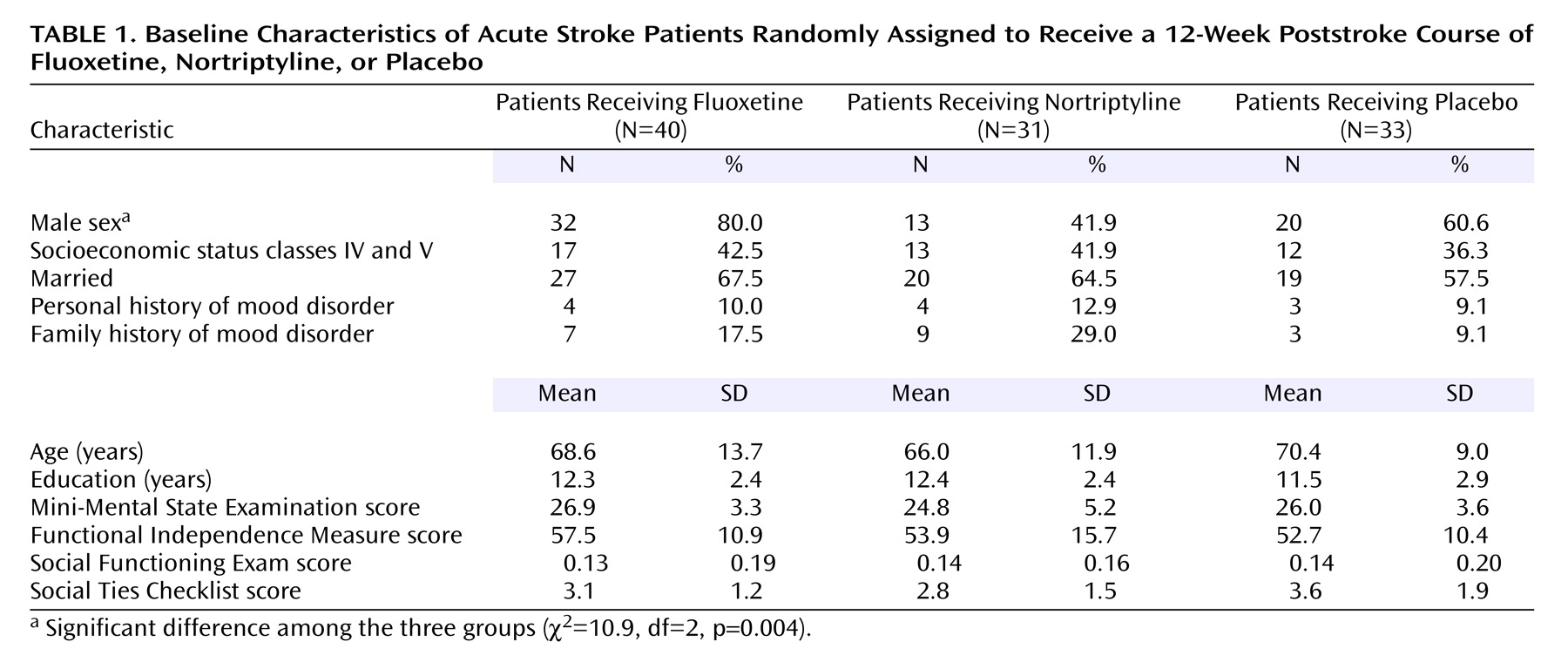

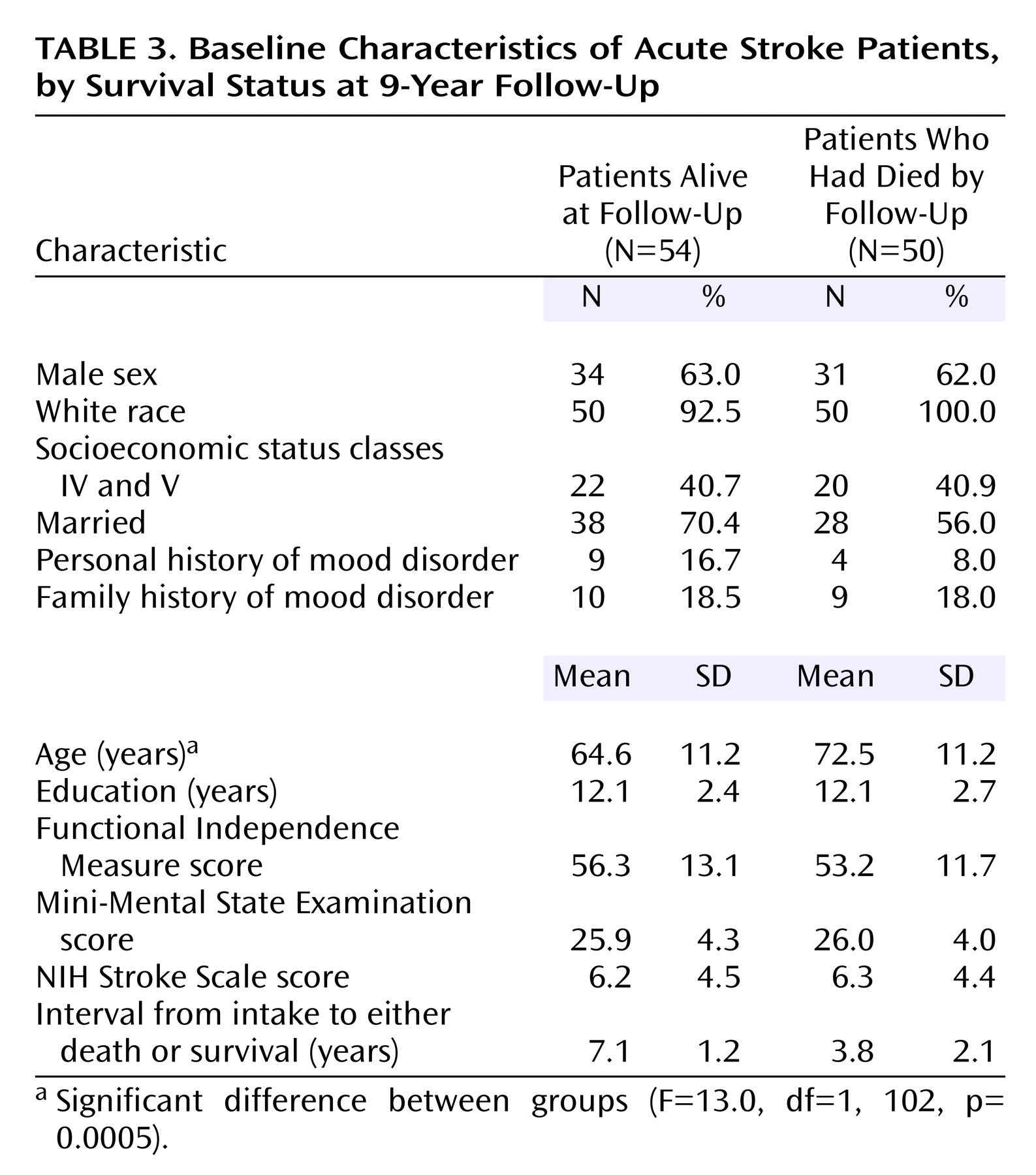

The patients who died were significantly older than the survivors (F=13.0, df=1, 102, p=0.0005) (

Table 3), but no other background differences were significant. There were no significant differences between the group of patients who died and the survivors’ group in the type and severity of the index stroke measured by NIH Stroke Scale score, in the location of injury, or in the frequency of any specific neurological symptoms. However, patients who survived were more likely to have had a cerebral hemorrhage (p=0.03, Fisher’s exact test).

No significant group differences were found between the patients who died and the survivors in baseline scores for impairment in activities of daily living as measured by the Johns Hopkins Functioning Inventory and the Functional Independence Measure, cognitive impairment as measured by the MMSE, or availability of social support as measured by the Social Ties Checklist (

Table 3).

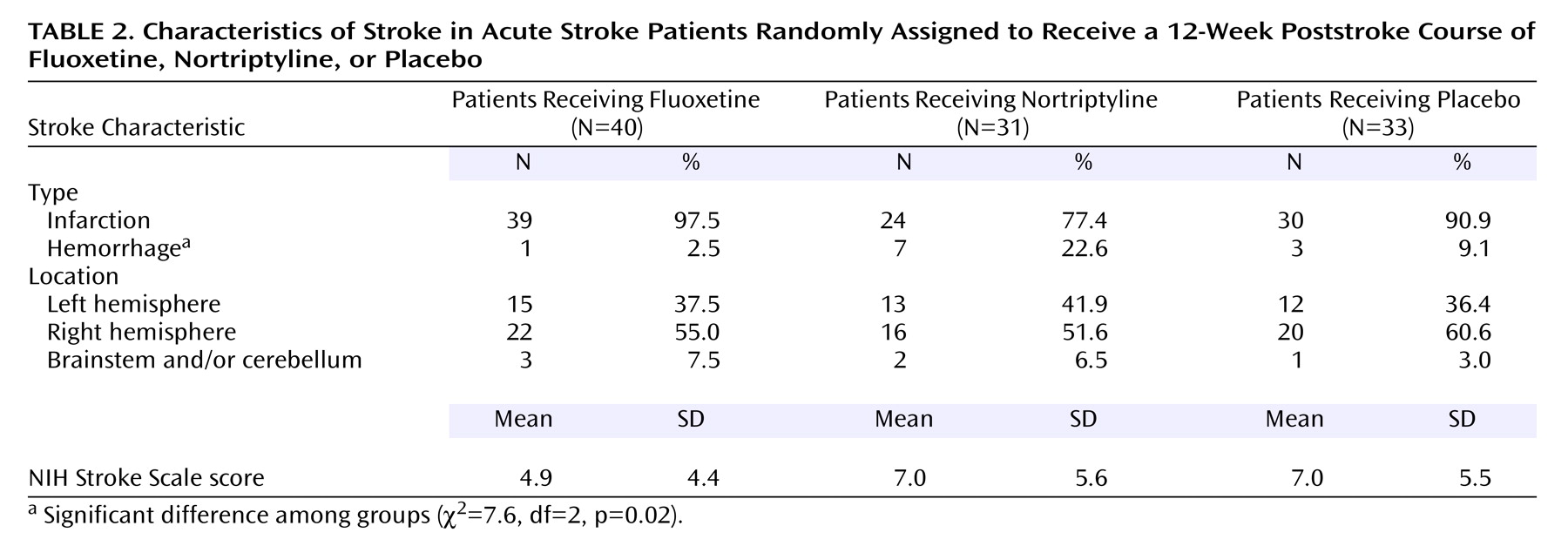

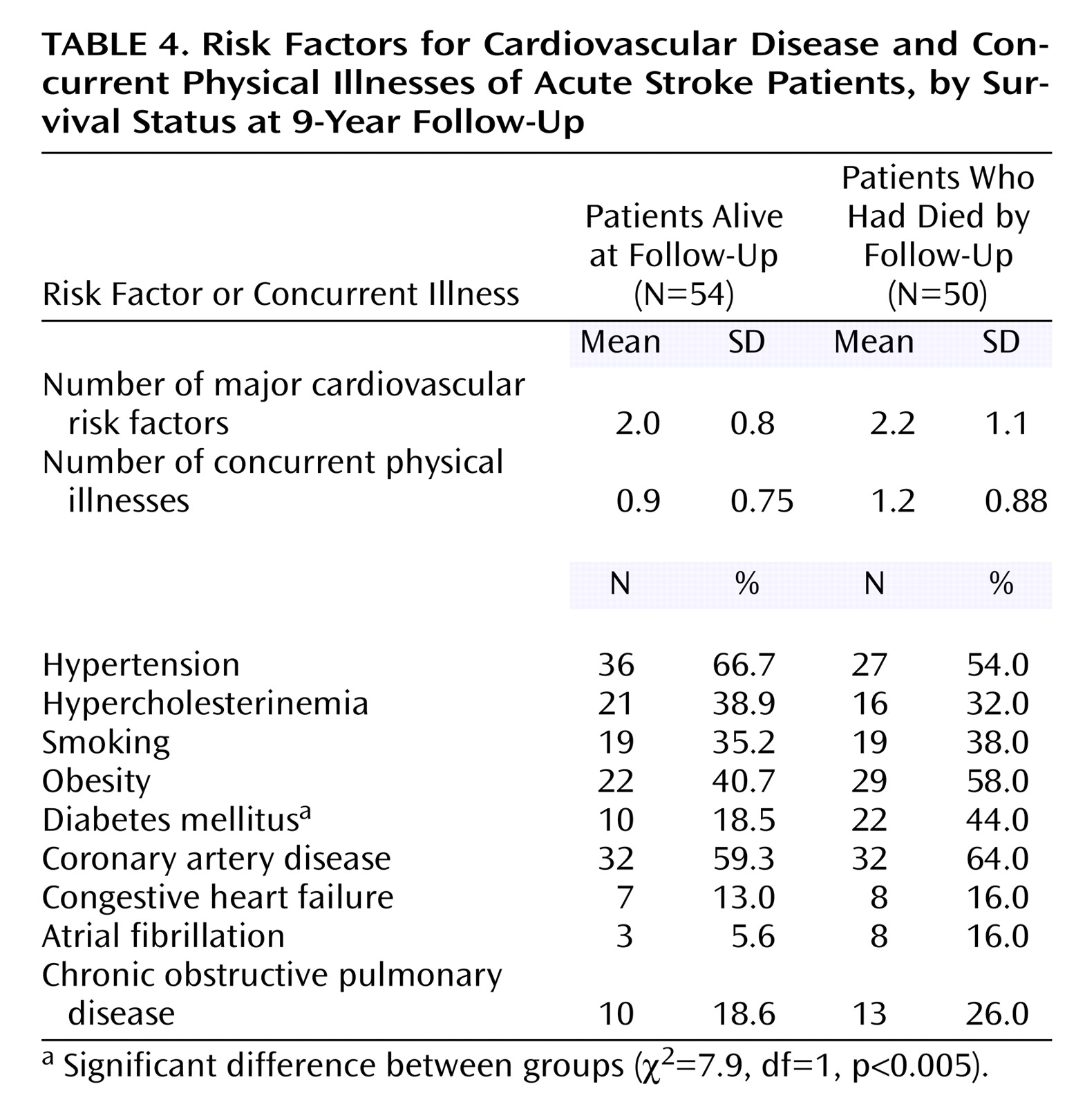

There were no significant differences between the group of patients who survived and the group of patients who died in the number of risk factors for cardiovascular disease or the number of concurrent physical illnesses (

Table 4).

There were no significant between-group differences in the frequency of arterial hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In addition, there were no significant between-group differences in the frequency of hypercholesterinemia, smoking, obesity, or alcohol use. However, patients who died were more likely to have a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (χ

2=7.9, df=1, p<0.005) (

Table 4).

Relationship of Mortality With Depressive Disorder

At baseline, 25 (50%) of the 50 patients who would die by the time of follow-up had a depressive disorder, compared with 31 (57.4%) of the 54 patients who would live. There was no significant association between depression at baseline and long-term mortality because many patients received adequate antidepressant treatment and experienced a sustained full remission of their symptoms. Initial Hamilton depression scale scores for placebo-treated patients who ultimately survived were not significantly different from initial Hamilton depression scale scores of placebo-treated patients who died (mean=7.3 [SD=3.7] and mean=6.4 [SD=5.1], respectively; F=0.24, df=1, 27, p=0.62). However, the small number of patients included in this comparison limits the statistical power to observe a significant difference.

Of the 58 patients who completed the 2-year follow-up evaluation, 22 developed a single episode of a depressive disorder that responded either to placebo or to antidepressant treatment. On the other hand, 14 patients had a chronic or relapsing course (i.e., no response to antidepressants or a response followed by a relapse or recurrence of depression). Twenty-two patients had no depressive disorder during the 2-year period. Of the 14 patients with relapsing depression, 10 patients (71.4%) died, compared with only six (27.3%) of 22 patients who responded and eight (36.4%) of 22 patients with no depressive disorder (χ2=7.3, df=2, p=0.02). Thus, the deleterious effect of depression on mortality rates was observed in those patients who had a chronic or relapsing clinical course.

Relationship of Mortality to Treatment With Antidepressants

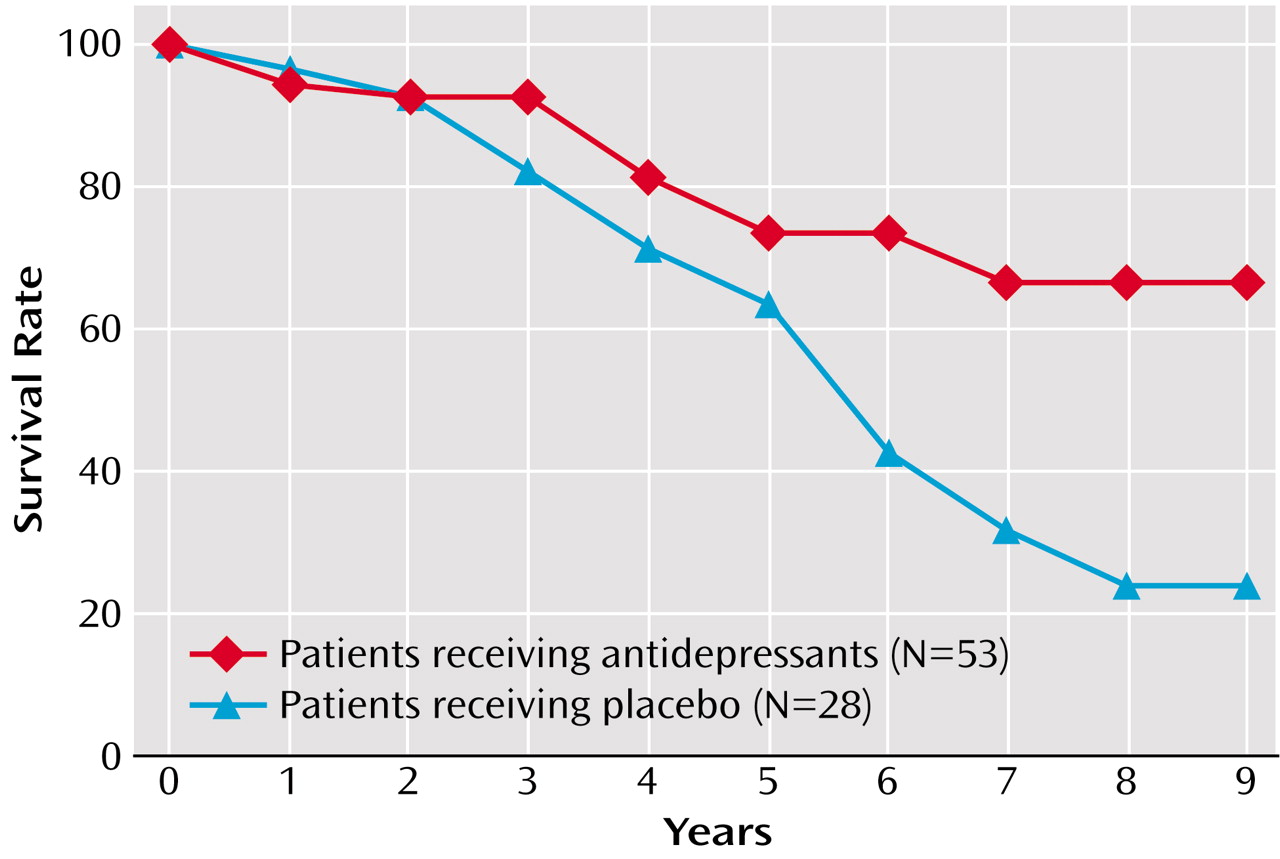

Intention-to-treat analysis showed that 42 of the 71 patients (59.2%) initially assigned to receive antidepressants were alive at 9-year follow-up, compared with 12 of the 33 patients (36.4%) who were assigned to receive placebo (χ2=4.7, df=1, p=0.03). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the probability of survival was significantly greater in the patients assigned to receive antidepressant treatment (χ2=4.7, df=1, p=0.03, log-rank test).

In the group of patients who completed the 12-week treatment protocol (N=81), 36 (67.9%) of the 53 patients treated with antidepressants were alive at the 9-year follow-up, compared with 10 (35.7%) of the 28 patients who received placebo (χ

2=7.7, df=1, p=0.005). The probability of survival was significantly greater in the patients who received antidepressant treatment (χ

2=8.2, df=1, p=0.004, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, log-rank test) (

Figure 1). Although decreasing the sample size has an effect on the power of statistical tests, the difference observed in survival rates between the patients receiving antidepressants and those receiving placebo continued to be significant after excluding the 12 patients recruited in Argentina (χ

2=3.8, df=1, p=0.05, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, log-rank test).

Nineteen of the 27 patients (70.4%) treated with fluoxetine were alive at follow-up, compared with 17 of the 26 patients (65.4%) treated with nortriptyline.

Twenty-seven of the 53 patients (50.9%) treated with antidepressants had major or minor depression at baseline, compared to 13 of the 28 patients (46.4%) who received placebo. The probability of survival was higher in the patients who received antidepressants in both the depressed (χ2=5.5, df=1, p=0.02, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, log-rank test) and the nondepressed groups (χ2=6.1, df=1, p=0.02, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, log-rank test).

Of the 17 patients who received adequate antidepressant treatment and died during the 9-year follow-up period, five patients (29.4%) died from cardiovascular causes, one patient (5.9%) died from recurrent stroke, and 11 patients (64.7%) died from other unrelated causes. On the other hand, of the 33 patients who did not receive adequate antidepressant therapy and who died, 18 patients (54.5%) died from cardiovascular causes, 11 patients (33.3%) died from recurrent stroke, and four patients (12.1%) died from other unrelated causes. The frequency of deaths attributable to vascular causes (i.e., cardiovascular disease and recurrent stroke) was significantly higher in the nontreated group (χ2=15.4, df=2, p=0.0005).

There were no significant differences between the group of patients who died and the group of patients who were still alive in the frequency of treatment with β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, digitalis, diuretics, anticoagulants, hypoglycemic agents, insulin, α blockers, antiplatelet agents, benzodiazepines, or other psychotropic agents.

Finally, a logistic regression model analyzing the association of mortality with the variables that were significantly associated with increased mortality rates (i.e., age, stroke type, comorbid diabetes mellitus, relapsing depression, and antidepressant use) found that antidepressants remained significantly associated with the probability of survival (Wald χ2=4.9, df=1, p=0.03), as did diabetes mellitus (Wald χ2=5.3, df=1, p=0.02).