Autism in a 15-Month-Old Child

Case Presentation

The parents of “Helen,” a 15-month-old girl, sought a developmental disabilities evaluation because of their concern that she had stopped vocalizing and using words in the previous 2 or 3 months. They had been concerned about her development from shortly after her birth because we had diagnosed her brother, who is 22 months older, with autism when he was 2 years old.

Pregnancy and Perinatal Period

Helen’s mother had severe nausea as well as thyroid disease (treated with levothyroxine sodium) during pregnancy. Labor was induced 2 days before the expected date.After delivery, Helen was kept in the newborn special care unit for a short period of time because her blood sugar was low, but she did well after discharge. She exhibited some colic and had difficulty with breast feeding but adjusted well to bottle-feeding. There was no report of unusual sensitivities during the first few months of life. Milestones were grossly in time. She smiled at 3 weeks of age, sat at 4 months, crawled at 6 months, and walked at 12 months. By that time, Helen was saying words such as “hi,” “baby,” “mommy,” and “daddy.” Normal development to this point was also documented by her pediatrician, who shared the parents’ concern given her older brother’s autism.Shortly after 12 months Helen stopped using words. Her parents associated this loss with a series of four ear infections that occurred within a span of 2 or 3 months and were treated with antibiotics. Along with the loss of verbalizations, the parents noted that Helen became increasingly less socially engaged. She did not bring things to her parents (e.g., to show, to request). At 15 months, she developed aversion to bright lights and loud noises. Although reported to be still affectionate with her parents, she typically ignored other people. At 15 months, Helen had not had a hearing test, nor had she received any form of therapy or intervention.

Assessment Results

Helen’s clinical evaluations at 15, 23, and 34 months included 1) developmental assessment (Mullen Scales of Early Learning [45]), 2) a speech, language, and communication assessment including both parent-report measures such as the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (46) and direct measures such as the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile (47), 3) a standardized diagnostic observational play protocol (module 1 of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule [48]) and a measure of adaptive behavior (Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales [49]). At the age of 15 and 34 months, a standardized parent interview (Autism Diagnostic Interview Toddler Version [50]) was conducted with Helen’s mother.

Assessments at 15 Months

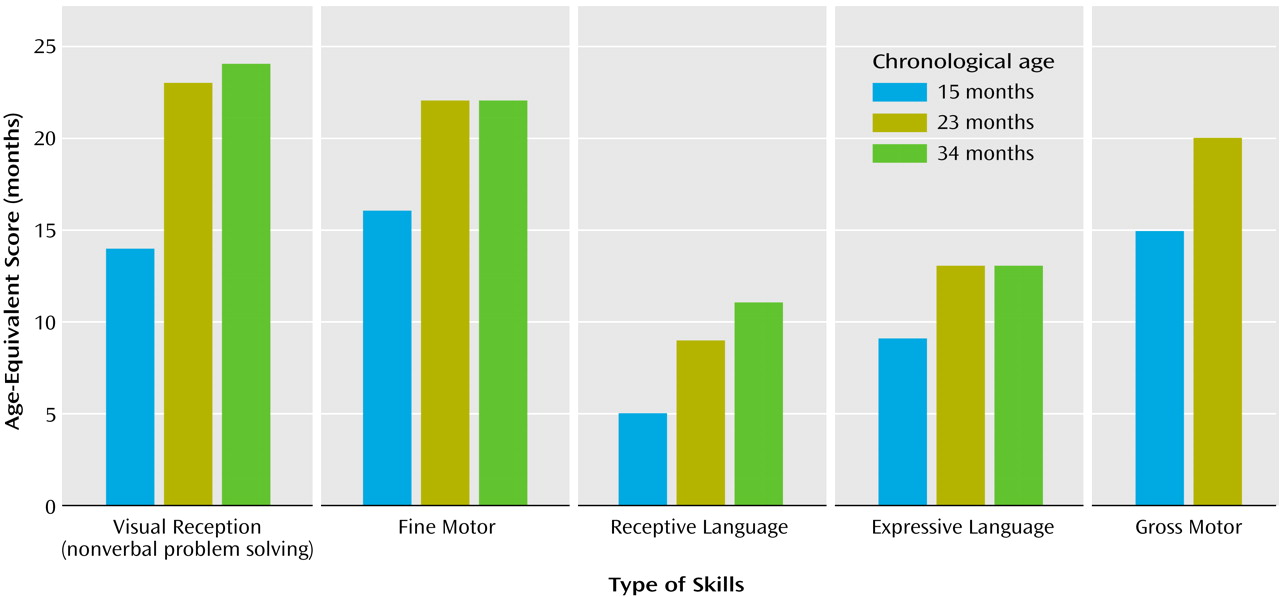

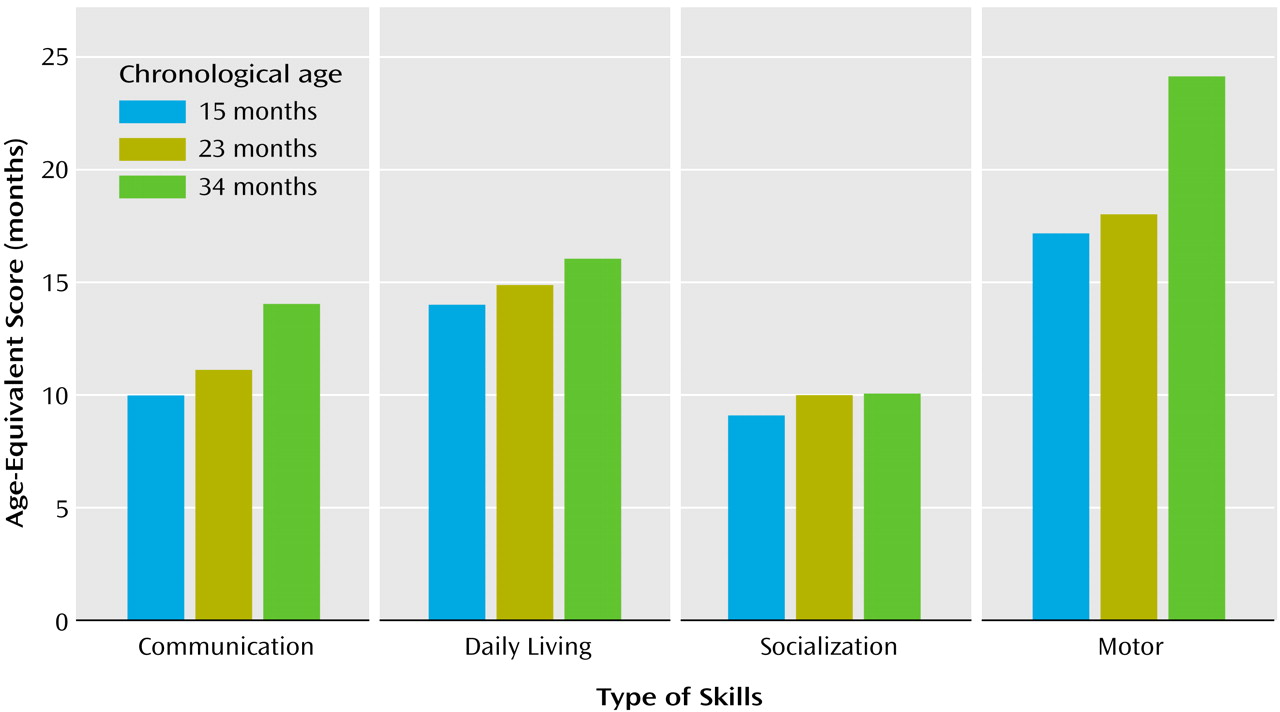

On the developmental assessment, Helen’s scores were within the average range for nonverbal problem-solving skills (e.g., functional use of objects, object permanence, emerging shape discrimination skills) with performance at the 14-month level (Figure 1). Her scores for fine and gross motor skills (eye-hand coordination, scribbling in imitation, running, walking upstairs with assistance, throwing a ball) were also within average range, with performance at the 15- and 16-month levels, respectively. She exhibited significant delays in language development, however. Her receptive skills were at about the 5-month level, and her expressive skills were at the 9-month level, indicating delays of 6 to 8 months.During testing Helen was unlikely to respond to simple verbal prompts (“sit,” “bye-bye”), verbal requests (“give me…,” “show me…”), even when paired with accompanying gestures or animated and playful vocalizations (including calling of her name). It was not possible to elicit a smile or vocalization without touching her. Helen did vocalize a great deal, but not in response or as an approach to other people. These vocalizations occurred primarily when she was exploring the environment alone or running aimlessly and did not appear to have a communicative purpose. Her vocalizations included consonant-vowel combinations but not words or word approximations. Helen’s only gestures were reaching for a desired object or pushing it away. These were unaccompanied by eye contact.During the diagnostic play session (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule), Helen was extremely self-isolated. If left to her own devices, Helen perseverated on exploration of cause-effect toys (e.g., blocks, pop-up toys) and objects with special textures, ignoring the examiner’s bids for engagement, which ranged from incidental comments or facial/bodily gestures to highly animated, exaggerated, and sometimes intrusive (less than 5 inches from her face) vocalizations and gestures. Eye contact was very infrequent and could not be elicited in a predictable manner. Her smiles were mostly in response to her own actions (flicking a doll’s eye back and forth) or in response to sensory experiences (e.g., lights, shiny objects). Helen could reenact some simple actions modeled by the adult (e.g., dipping a bubble stick inside a little bottle with soapy water) but typically would not imitate the examiner’s entire goal-directed behavior (e.g., making soap bubbles) or the examiner’s style (e.g., exaggerating specific aspects of the movements). It was not possible to engage Helen in early anticipatory or imitative games (e.g., peek-a-boo), she did not appear to learn from the adult’s attitudes toward novel objects (e.g., she continued to be fearful of a mechanical bunny despite the examiner’s exaggerated displays of affection toward the toy animal), and, if forced to make eye contact, she typically focused on the periphery (e.g., hair, chin) of the approaching adult’s head or overly fixated on the adult’s mouth. She was not interested in nor did she explore any of the miniatures (e.g., people, furniture) or representational toys for any length of time. She mouthed the miniatures, very much like she mouthed nonrepresentational toys. There were no episodes of symbolic play. She vocalized infrequently. When frustrated, she made high-pitched sounds that were self-stimulatory rather than communicative. She was extremely independent, almost never using the adult to get something she wanted. She did not point to request something from or to show something to the adult or her parents, who were also in the room. She was not sensitive to exaggerated gaze cues or pointing gestures (i.e., she did not look in the direction of the adult’s gaze or pointing).Her attention shifted quickly from object to object. If unable to secure a desired object, she mouthed what she had in her hands. She showed a number of self-stimulatory behaviors and unusual sensitivities. She flapped her arms and held her arms, hands, and fingers in unusual postures. Her disregard of the social approaches of others contrasted markedly with her acute awareness of inanimate details of the environment (e.g., finding a small piece of candy some 8 feet away from the play area). She was easily scared by noises and novel events (e.g., the noises of a balloon deflating), startling repeatedly until the adult discontinued the activity.The speech, language, and communication assessment took place in a highly animated interactional environment to maximize social engagement and speech and communication production through familiar play routines (e.g., dancing, nursery rhymes, wind-up toys, blowing bubbles). By parent report, expressive and receptive language were delayed, with vocabulary production at 9 months, gesture production at 12 months, vocabulary comprehension at 8 months, and phrase comprehension at less than 8 months.None of the gestures Helen displayed during assessment were conventional—no pointing, nodding, or showing were noted. Helen’s gestures consisted primarily of depictive and physical gestures, made to complete a physical routine (e.g., reenacting the motions of “Ring Around the Rosie” and pulling on the examiner’s hand to request falling “down”) or as a means to an end (e.g., moving a bubble jar to the examiner to see more bubbles) rather than communicative requests or attempts to share an experience with her play partner. In more spontaneous situations, Helen was extremely independent in getting desired objects and was likely to express frustration by moving the examiner’s hands away rather than making eye contact or otherwise directing her communication to the adult. By parent report, Helen was more likely to use her parents to obtain desired things in the environment, although she was also likely to discontinue this contact if her idiosyncratic gestures or vocalizations did not achieve the desired result. She sometimes sought physical proximity to her parents when distressed (e.g., when frightened of sudden noises), but not often. She was able to respond to verbal directions only in the context of strong visual cues (e.g., “give me” paired with an open palm and a toy bag), following predictable carrier phrases (e.g., “ready, set, go”), and routines (e.g., “if you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands”). Vocal and gestural imitation could be elicited only in these situations, and very inconsistently.With regard to adaptive skills, Helen’s profile on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales showed great scatter (Figure 2). At 15 months of age, daily living skills and motor skills were at or above age level (at 14- and 17-month levels, respectively); in contrast, there were significant delays in communication (10-month level) and, particularly, socialization (9-month level) skills. Helen’s parents reported somewhat higher receptive language skills in more familiar contexts (14 months) than those observed during the formal assessment and expressive language skills (approximately at the 8-month level). Her interpersonal relationships were at the 7-month level, and her play skills were at the 10-month level. Several social responses typically seen in the first 6 months of life were not present at 15 months of age (e.g., following a person moving around with her eyes, smiling to make social contact, looking for a familiar person when in need of attention).

Genetic and Neurological Evaluation

As noted, Helen’s brother had been diagnosed with a prototypical form of autism a short time before her birth. Otherwise there was no family history of autism or other developmental disorder in the immediate or extended family. Helen underwent genetic evaluations at 17 and 20 months. By report, Helen and her then 3.5-year-old brother with autism appeared to have lost some skills at around 12 months, although Helen lost words and social skills and her brother only the latter (he did not have words at that time). Both Helen and her brother are macrocephalic, which appears to be a family trait (the father’s head circumference is 58 cm [90th percentile], and the mother’s is 58 cm [>95th percentile]). Both children had accelerated head growth, although at different times. Both of them also showed accelerated weight and length gain, but not as dramatic as their head circumference. Helen’s head circumference went from the 50th percentile at 6 months to >95th percentile by 9 months (stabilizing thereafter), whereas her brother went from slightly below the 50th percentile at 2 weeks of age to the 95th percentile at 2 months and >95th percentile at 4 months (stabilizing thereafter). Helen’s weight was at the 75th percentile at 2 months, 90th percentile at 4 months, and >95th percentile at 6 months; her length was at the 75th percentile at 2 months and the 90th percentile at 4 months, continuing to fluctuate between the 75th and the 95th percentile until 24 months. Her brother’s weight was at the 95th percentile by 2 months and remained so until 24 months; his length was at about the 35th percentile at 2 months and fluctuated between the 75th and 95th percentile from 4 months to 24 months.On examination at 15 months, Helen was essentially nondysmorphic, except for some minor distinctive features, including a prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, flat nasal bridge, and tapered digits (features that were similar to her brother’s). Results of head ultrasound were normal. There were no neurocutaneous lesions to suggest either tuberous sclerosis or neurofibromatosis. A series of genetic and metabolic tests were performed, and the results were all normal. These included fragile X polymerase chain reaction, subtelomeric fluorescence in situ hybridization (for chromosomal microdeletions), karyotype, urine purine and pyrimidine analysis, guanidinoacetate (for creatine synthesis defects presenting as developmental arrest, often with seizures), urine organic acids (for organic acidurias and mitochondrial disorders), fasting plasma and amino acids (for mitochondropathies and aminoacidopathies), lactate/pyruvate, and creatine phosphokinase (additional screening for mitochondrial disorders). Helen’s brother had results on normal antigliadin and antiendomysial antibody screens for celiac sprue (carried out because of his alternating constipation and diarrhea). He also had normal results on EEG and brain magnetic resonance imagining scan, carried out after he had one seizure. Results of Helen’s neurological examination were essentially normal. She had a 24-hour EEG with no findings.

Diagnostic Formulation and Early Intervention Services

At the time of Helen’s 15-month assessment, the diagnostic impression by all the clinicians was autism. Unlike some very young children, Helen also met criteria for autism on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and on the Autism Diagnostic Interview. The program of early intervention prescribed included an intensive and highly structured and individualized therapeutic schedule consisting of speech- and language-based functional activities delivered by specialized educators and communication therapists as well as direct family training and support. Although a substantial body of work exists on intervention programs for slightly older children (1), information on intervention for infants is limited; therefore, we adapted principles for intervention used in slightly older children for Helen in the light of her particular pattern of strengths and weaknesses.Goals for her program included the following: 1) to increase Helen’s rate of spontaneous and intentional communication by designing the environment to provide opportunities for her to independently initiate communicative acts (e.g., communicative “temptations,” reinforcement of eye contact and gestures directed at adults, use of predictable carrier phrases), 2) to increase Helen’s capacity to communicate for behavior regulation (e.g., to request actions and access to desired objects, to protest), 3) to increase her capacity to communicate for engaging in social interaction (e.g., calling attention to oneself, requesting continuation of a social routine, requesting comfort, showing off, greeting others), 4) to increase Helen’s capacity to bring attention to objects or events for the purpose of joint attention (e.g., commenting and requesting information), 5) to increase Helen’s repertoire of gestural communication (e.g., pairing of giving and pointing gestures with gaze and conventional gestures such as waving bye-bye and “all done”), 6) to increase Helen’s single-word vocabulary through the use of a photo/picture communication system, 7) to facilitate comprehension of language by repeated exposure to one- or two-word phrases corresponding to common actions (e.g., “wash hands,” “put in,” “all done”) as well as labels of common objects (e.g., puzzle, book), and 8) to facilitate engagement in symbolic play by adult-directed use of miniatures to mirror Helen’s own real-life, familiar, and repetitive events. Specific recommendations were also made for enhancing Helen’s adaptive level of functioning in the areas of communication, daily living skills, and socialization.

Follow-Up Assessments at 23 and 34 Months

By 18 months, Helen had pressure-equalization tubes placed because of repeated ear infections. Following that, she was reported to produce a wider range of sounds. Therapy had begun with a speech and language therapist, but only once a week for 1 hour. Two additional hours of therapy were provided by a special education teacher under the supervision of the communication specialist. Helen also joined two small play groups, but her participation was minimal because of her self-isolation. Helen’s parents brought her to a brief consultation for a diagnostic play session 2 weeks after the pressure-equalization tubes were placed. Helen’s presentation was virtually unchanged since the evaluation at the age of 15 months.At the age of 23 months, Helen completed a reevaluation consisting of developmental assessment (Mullen Scales of Early Learning), diagnostic play (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule), and measurement of adaptive behaviors (Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales). Her profile of strengths and deficits on developmental assessment (Figure 1) was unchanged relative to her evaluation at the age of 15 months, with encouraging gains in nonverbal cognitive functioning (going from the 14-month level to the 23-month level), fine motor skills (from 15 months to 22 months), and gross motor skills (from 16 months to 20 months), but only minimal gains in receptive language (from about 5 months to 8 months) and in expressive language (from about 9 months to 13 months). Helen’s Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule scores were virtually unchanged, indicating a highly stable level of symptoms.Absolute progress in the acquisition of adaptive skills in all areas of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales was minimal, with the resultant drop in standard scores. At the age of 23 months, Helen’s age equivalent scores in the communication and socialization domain were at the 10-month levels (Figure 2). These results prompted a renewed and more concerted effort to secure intensive, appropriate, and specialized interventions, adding a core element of “learning to learn” skills (e.g., facilitating more active engagement in adult-led activities following highly routinized and behaviorally based learning tasks). Additionally, it was evident that a significant increase in the number of hours of her intervention program was warranted (her service providers had been unsure of the diagnosis and the need for intensive services).Results of the 34-month assessment were less encouraging in terms of progress made. In contrast to the previous year, the absolute gains on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning were minimal (Figure 1). In the 11-month interim period, Helen gained only 1 month in nonverbal cognitive functioning (24-month level), 3 months in receptive language (11-month level), 1 month in expressive language (14-month level), and no change in fine motor skills (22-month level). Helen’s gross motor skills were not assessed because she was unable to attend to or imitate most of the gross motor probes.The diagnostic play session (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) revealed a pattern of scores that was virtually unchanged relative to the two previous assessments. Helen’s acquisition of adaptive skills was also stunted. She gained approximately 4 months in the 11-month period in the area of communication, her daily living skills advanced 1 month during that time, and there were no gains in the area of socialization. The most growth was noted in motor skills (6 months) (Figure 2).

Discussion

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).