Bipolar disorder is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide and carries a substantial risk of suicide

(1). Individual episodes of depression and mania can usually be successfully treated, but relapse is common. Prevention of relapse is therefore important to reduce the disability caused by recurrent illness. Lithium was the standard treatment for relapse prevention over several decades since publication of early trials of lithium treatment in the 1960s and 1970s. This is no longer the case, especially in North America. In part, this followed the growing recognition that lithium is not as effective for most patients as was initially believed. There is also the perception that lithium use poses particular problems, such as adverse effects and poor patient adherence

(2–

4), dose uncertainty, and the occurrence of withdrawal mood episodes upon sudden discontinuation

(5,

6). Also, in recent years, anticonvulsants have been strongly promoted as alternatives to lithium and are commonly described as mood stabilizers.

The discarding of lithium in North America is regularly lamented by many leading authorities in the treatment of bipolar disorder. However, we believe that any defense of lithium’s continued use must be based more on evidence than opinion. There have also been further critiques of the evidence

(7), and at the time of this criticism there seemed little likelihood that further trials could be completed to address the new objections.

This situation has changed, and several recent trials investigating new medicines for bipolar disorder have included a lithium comparison arm. These trials have produced substantial new data on the long-term efficacy of lithium. It is, therefore, timely to reevaluate the evidence for the efficacy of lithium. The increased volume of data also now allows us to address the relative efficacy of lithium in preventing relapse to the manic and depressive poles of the illness. We report a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing lithium with placebo in the prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder.

Results

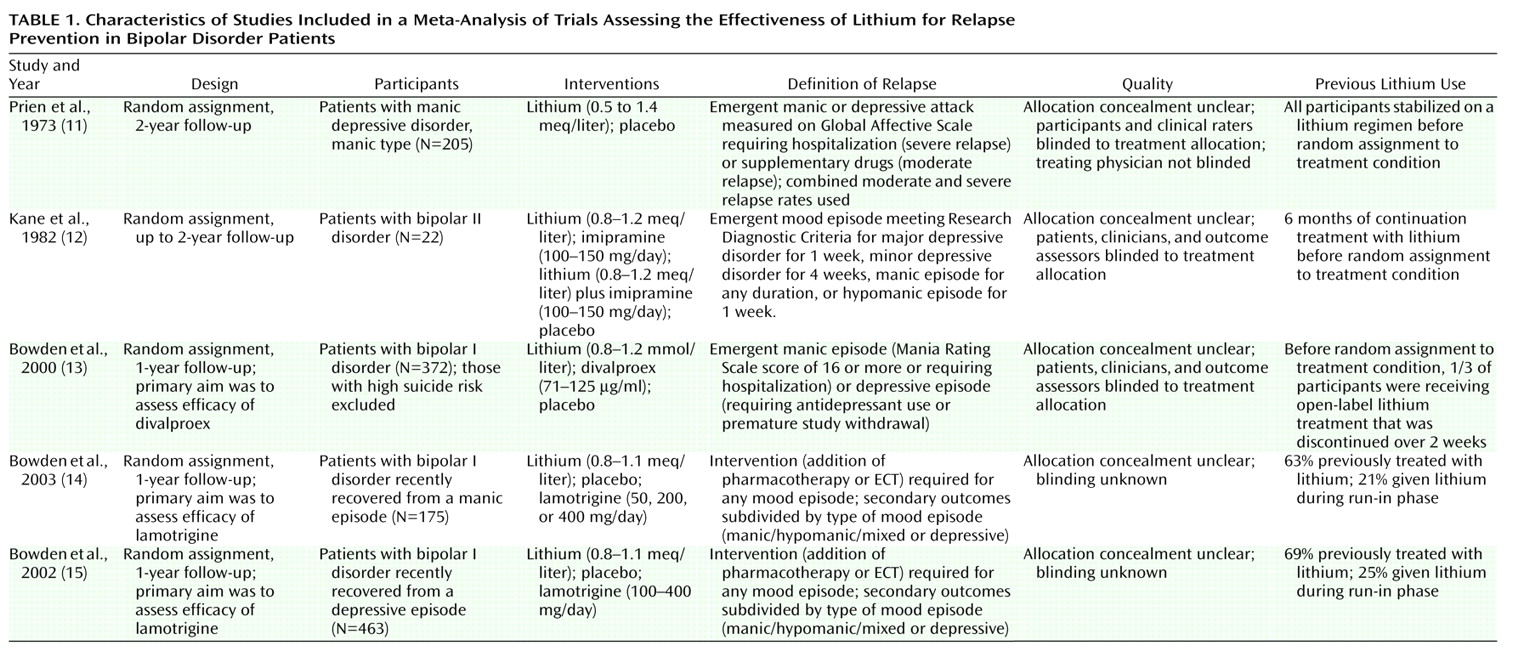

Over 300 articles were screened. Of these, five were randomized trials that compared lithium with placebo in bipolar disorder patients (N=770) and were thus included in the analyses (

Table 1). No randomized trials with sudden discontinuation of lithium that included only stable bipolar patients were identified. One trial

(12) had a factorial design in which participants were randomly assigned to imipramine versus placebo and separately to lithium versus placebo. The lithium versus placebo comparison was included (ignoring the imipramine versus placebo comparison). The trials followed participants either until relapse or for maximum periods of between 11 months and 4 years. Lithium levels were reported in five trials and were between 0.5 and 1.4 mmol/liter.

Quality ratings are shown in

Table 1. Although trials in which long-term lithium was discontinued in stable patients were excluded from the analyses, some participants in the included trials had varying degrees of previous exposure to lithium before being randomly assigned to a treatment condition. In one trial, all participants had been stabilized on a regimen of lithium following remission of the acute episode and before discharge from the hospital

(11); in others, one-third

(13) and two-thirds

(14) of the participants received open-label treatment with lithium before randomization. In the trials that included a lamotrigine arm, participants were randomly assigned to a treatment group if they remained stable during an open-label run-in phase during which they were receiving lamotrigine, and it is possible that these trials selected those patients who were lamotrigine responders and excluded some lithium responders

(14,

15).

Relapse was defined somewhat heterogeneously in the trials, although all except one

(12) used some form of clinical action (initiation of a new treatment or admission to hospital) as defining a clinically significant relapse (

Table 1). This might explain the variation in absolute event rates in the trials, although it is perhaps more likely to reflect the heterogeneity in the patient populations. For example, the placebo relapse rate in the first year in Prien et al.

(11) was 67%, with 57 of 71 relapsed patients being admitted to the hospital. The 12-month placebo relapse rate in Bowden et al.

(13) was 38%. As suggested elsewhere

(16), this probably reflects the milder nature of the disorders in the later trial.

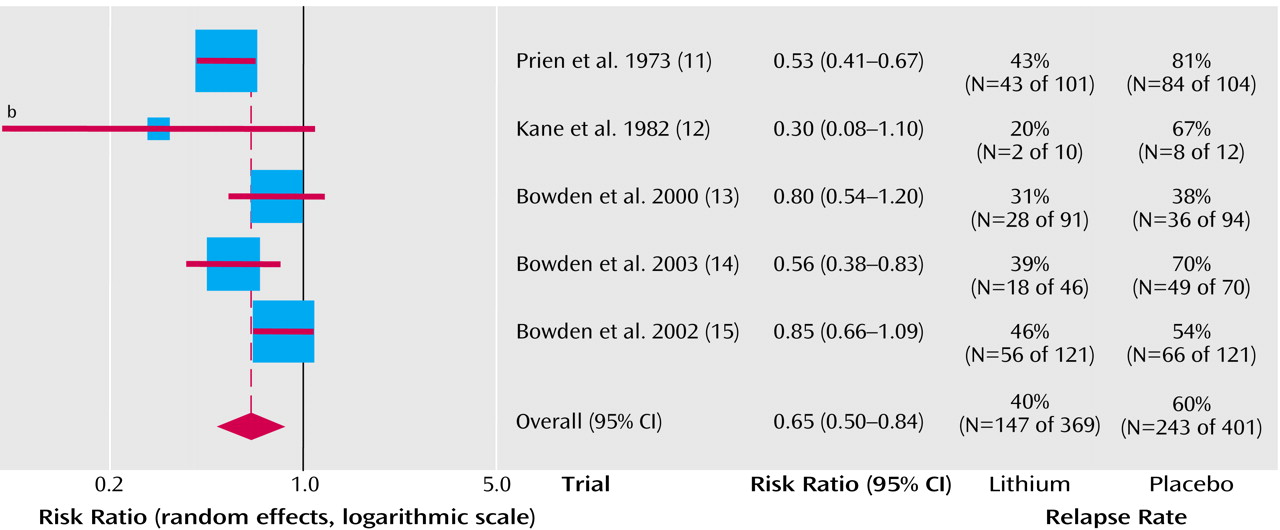

Lithium was more effective than placebo in preventing any new episodes of mood disturbance (fixed effects relative risk=0.66, 95% CI=0.57–0.77 [p<0.0001]; random effects relative risk=0.65, 95% CI=0.50–0.84; p=0.001) (

Figure 1). The statistically significant heterogeneity (χ

2=10.08, df=4, p=0.04) was judged to be quantitative because all the trials found a benefit for lithium over placebo, although this was not always statistically significant. The average risk of relapse in the placebo group was 60% compared with 40% for lithium. This means that one patient would avoid relapse for every five patients who were treated for a year or 2 with lithium.

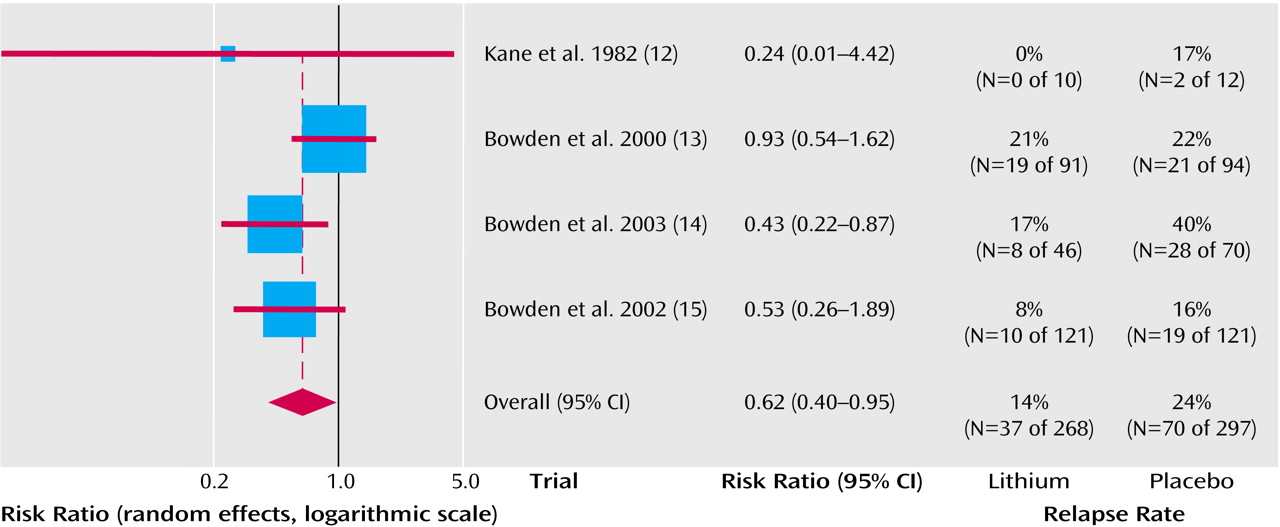

Lithium was superior to placebo in the prevention of manic episodes (fixed effects relative risk=0.62, 95% CI=0.43-0.88 [p=0.008]; random effects relative risk=0.62, 95% CI=0.40-0.95 [p=0.03]) (

Figure 2). Statistical heterogeneity was not seen (χ

2=3.89, df=3, p=0.27). The average risk of relapse in the placebo group was 24% compared with 14% for lithium. This means that one patient would avoid relapse for every 10 patients who were treated for a year or 2 with lithium.

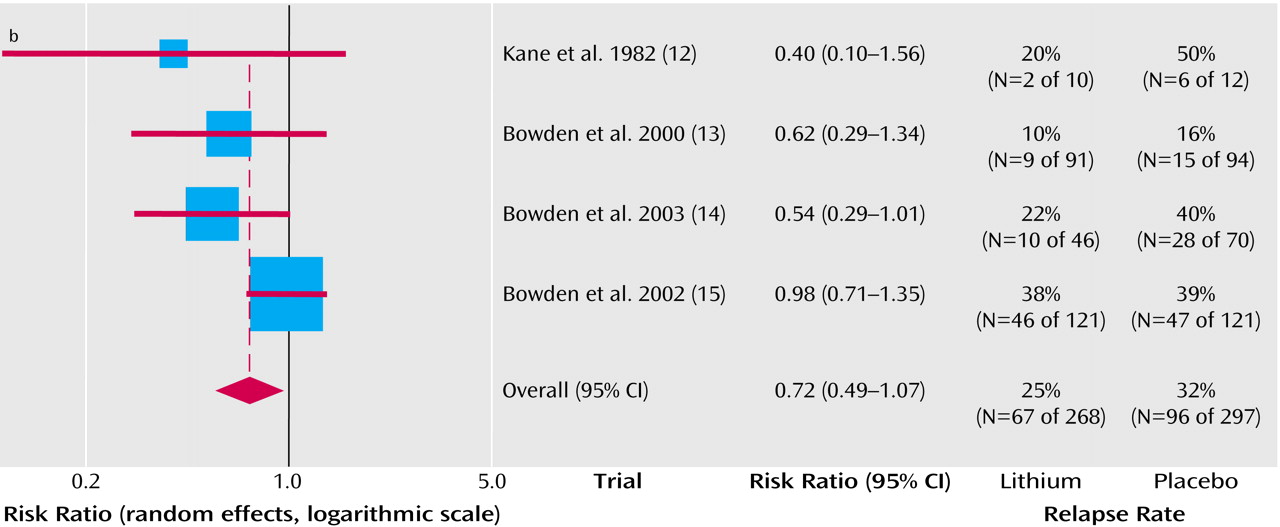

As seen in

Figure 3, the effect on depressive relapses appeared smaller and just failed to reach statistical significance (fixed effects relative risk=0.78, 95% CI=0.60–1.01 [p=0.06]; random effects relative risk=0.72, 95% CI=0.49–1.07 [p=0.10]). Statistical heterogeneity was not seen (χ

2=4.67, df=3, p=0.20). The average risk of relapse in the placebo group was 32% compared with 25% for lithium. This means that that one patient would avoid relapse for 14 patients who were treated for a year or 2 with lithium.

Overall withdrawal from the trials was lower with lithium than with placebo (fixed effects relative risk=0.86, 95% CI=0.80–0.93). The following specific adverse effects were statistically more common with lithium than with placebo: somnolence (relative risk=1.98, 95% CI=1.02–3.84; absolute risk=13%); nausea (relative risk=1.76, 95% CI=1.07–2.92; absolute risk=20%); and diarrhea (relative risk=2.35, 95% CI=1.35–4.10; absolute risk=20%). Hypothyroidism occurred in 4% of treated patients (relative risk=9.26, 95% CI=0.51–169.91).

There were few suicides in the trials (lithium: N=0 of 268; placebo: N=2 of 297; fixed effects relative risk=0.32, 95% CI=0.03–2.98).

Discussion

One of the most striking findings of our review of the efficacy of lithium in bipolar disorder is that, in terms of the number of patients randomly assigned, over 70% of the total high-quality randomized evidence has been published or reported since 2000. This is because trials of novel long-term treatments have included a lithium comparison group. The substantial increase in the total randomized evidence over the last few years means that we now know far more about the benefits and common adverse effects of lithium than we did during the first 50 years of lithium’s clinical use in psychiatry. Our earlier meta-analysis of lithium in bipolar disorder included only three trials and 412 participants

(17).

The current meta-analysis provides more satisfactory evidence that lithium is more effective than placebo in preventing relapse in bipolar disorder. In the patients participating in the trials, lithium treatment on average reduced the overall risk of relapse during follow-up from 61% to 40%, which is certainly a clinically worthwhile effect. For patients at lower average risk of relapse (e.g., those earlier in their course of illness), the benefits and costs of long-term treatment will need to be carefully appraised in each individual case. Evidence is emerging that, in addition to the considerable psychosocial dysfunction caused by relapses

(1), recurrent episodes cause additive and persistent neuropsychological impairment, and many patients may choose to start long-term lithium treatment earlier rather than later in the course of the illness

(18).

The protective effect of lithium is most clear for manic episodes: lithium substantially reduces the risk of relapse by about 40% (from 24% to 14%). The situation is more equivocal for depressive relapse because the relative risk reduction is smaller (22%) and the 95% confidence interval of the pooled estimate includes the possibility that there is no treatment effect. The finding that lithium is probably more effective against mania than depression is consistent with clinical experience. It is important to note, however, that the evidence from our review is consistent with a moderate beneficial effect, rather than the absence of an effect against depressive relapse. It is likely that some patients will be protected by lithium against both manic and depressive relapses. The earlier studies that included patients with unipolar depression as well as bipolar patients were, of course, also positive, which again implies some efficacy against depressive relapse

(17).

Data from these randomized trials were insufficient to estimate the possible suicide prevention effect of lithium that was suggested by a recent review of nonrandomized studies

(19).

We decided, a priori, to exclude trials in which stable patients—who had been well on long-term lithium regimens—were abruptly switched to placebo, although no such trials were actually identified. This minimizes the possibility of discontinuation effects confounding the results of this review. However, the significance of mania following acute lithium withdrawal remains interesting, and it would be wrong to assume that studies of this design subvert lithium’s claims to efficacy. European regulators actually recommend discontinuation designs for new drugs for which there are claims of proof of maintained efficacy

(20). The reasoning is that a maintenance claim requires evidence of an initial response (say, in acute mania) and then independent evidence that withdrawal of the drug leads to subsequent relapse. On this basis, lithium has a strong claim for maintained efficacy. The alternative view is that maintenance should mean that lithium prolongs full recovery by preventing new episodes. In Europe, where it is common to treat acute mania or depression before adding lithium, the use of lithium is not to maintain an acute response but to maintain remission. We do not know if there is a real difference between these two approaches. In practice, remission is a hypothetical state, assumed to be present after a period of euthymia.

A wholly unbiased measure of average preventive efficacy would require recruitment of patients without pretrial exposure to lithium. None of the trials definitely excluded patients with previous lithium exposure. However, it is unlikely that discontinuation alone could account for the benefit of lithium over placebo seen in these studies. It is notable that relapses in placebo groups were not clustered in the early months of studies. In the early NIMH trial

(11), there was no major difference in relapse rates between year 1 and year 2 of the study. Therefore, lithium showed maintenance efficacy whether or not there was a contribution from its discontinuation.

This review supports the use of long-term lithium treatment to prevent relapse in patients with bipolar disorder, particularly in those patients for whom the main burden of disability is secondary to mania. The majority of the randomized evidence now comes from recent, well-conducted trials. Although these trials were sponsored by industry, they were designed to test novel treatments, and it is most unlikely that the design and procedures were biased in favor of lithium. Patient selection into placebo-controlled trials may limit generalizability and, indeed, the real-world effectiveness of lithium maintenance treatment may be less than the efficacy estimated by these trials. Since abrupt discontinuation carries a risk of relapse, clinicians should carefully assess their patients’ likely adherence to treatment and educate them fully on the risks of discontinuation relapse before commencing treatment

(5).

It is unlikely that further randomized trials primarily designed to assess the efficacy of lithium compared with placebo will be attempted. However, the inclusion of a lithium comparison arm in future trials of new agents may further refine our estimate of the treatment effect against depressive relapse. This uncertainty about the efficacy of lithium remains, highlighting the discrepancy between its widespread use over many years in millions of patients and the still modest numbers in randomized trials. However, it remains the best studied drug for the prevention of relapse in bipolar patients. Its continuing use is evidence-based and should be considered by clinicians and individuals with bipolar disorder. The challenge for the future is to decide how and when it can best be employed, alone or in combination with other effective agents, to improve the outcome in individual patients.