Beginning with early ethnographic studies, differences in the course of Native American drinking that might give clues to its nature and etiology have been sought

(2–

4). One drinking pattern that has been fairly extensively commented on is binge drinking

(5–

8). Binge drinking is often described as an intense bout of drinking in which large amounts of alcohol are drunk over a period of days and is terminated only when all readily available sources of alcohol are used up or unconsciousness occurs

(9). Another aspect of Native American drinking that has been reported is the “aging-out” phenomenon (see references

10 and

11). Levy and Kunitz

(12,

13), relying on data collected in an extensive longitudinal study, reported that many Navajo (between 21% and 53%, depending on geographic location) stop drinking when they reach middle age. It has been suggested that aging out often occurs without recourse to any formal treatment program

(14,

15). Anecdotal reports of Indian binge drinkers who purportedly drank heavily for many years and stopped drinking, apparently without difficulty, in middle age without serious physical, psychological, or social sequelae have been used as examples to suggest that Indian drinking may be substantially different in nature from that seen in other ethnic groups

(15). These kinds of case reports have also been used to argue against the presence of severe “dependence” on alcohol in such individuals.

A series of studies investigating alcoholism in several different tribes using standard diagnostic instruments have provided a somewhat different view as well as quantitative information on the nature and consequences of drinking in Native Americans. Robin et al.

(16) studied binge drinking in a Southwestern tribe and concluded that it was associated with DSM-III-R alcohol dependence and was related to deleterious consequences in functioning. In a study of Southern Cheyenne Indians, alcoholism was usually severe, often co-occurred with other substance abuse, and had an early age at onset (<25 years)

(17). An evaluation of Alaskan Natives entering alcohol treatment also found a severe form of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence

(18). Additionally, a study of Northwest urban American Indians in a number of treatment settings found that this population was plagued by the chronicity and recidivism of its alcohol problems

(19). Thus, the empirical data to date suggest a high prevalence and early age at onset of severe alcoholism in the several Native American tribes that have been studied.

Differences in findings between studies could reflect a number of potential factors. Different tribes and communities were studied, and tribes without high rates of alcohol dependence were not included. Additionally, some studies have investigated Native Americans living in rural communities, many of whom had never sought or received treatment for alcohol problems, whereas others focused exclusively on urban treatment populations

(20). Having extensive quantitative information on the nature and course of alcoholism, even in one Native American tribe or community, has important implications. If alcoholism can be subtyped in a group of individuals, then the resulting phenotype can be used to help understand the component of alcoholism that is genetically transmitted. Alternatively, a knowledge of specific aspects of the disorder that are influenced by unique environments, such as reservations, may lead to better prevention programs tailored to those communities. Knowing the natural course of a disorder can also be important in both teaching clinicians to better recognize the illness and guiding them on its prognosis

(21).

Method

Mission Indians who were of mixed heritage but were at least 1/16 Native American were targeted for study and were recruited from six geographically contiguous Indian reservations with a total population of about 3,000 individuals. Participants who were mobile and between the ages of 18 and 70 were recruited by using a combination of a venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations

(28,

29) and a respondent-driven procedure

(30). The venues included tribal halls and cultural centers, health clinics, tribal libraries, and stores on the reservations. A 10%–25% rate of refusal was found, depending on the venue. Refusal rates were higher at tribal libraries and stores than health clinics and tribal halls or culture centers.

The protocol for the study was approved by two internal institutional review boards and the Indian Health Council, a tribal review group overseeing health issues for the reservations where the recruitments were made.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after the procedures had been fully explained. Participants were compensated for their time spent in the study. Each participant (N=407) completed an interview with the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism, which was used to gather demographic information and make a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol dependence according to DSM-III-R criteria. The Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism is a polydiagnostic psychiatric interview that has undergone both reliability and validity testing

(27,

31). It has been successfully used in Native American populations previously

(18,

32). Interviewers were all trained by personnel from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). All best final diagnoses were made by one research psychiatrist/addiction specialist (D.A.G.). In addition, the interview retrospectively asks about the occurrence of alcohol-related life events and the age at which the problem first occurred.

The major statistical approach focused on the three specific aims. The rate and age of the occurrence of 39 alcohol-related life events were obtained from the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism for the participants who were alcohol dependent at any time in their lives. The effects of gender (men versus women) and percent Native American heritage (<50% and =50%, according to their federal Indian blood quantum) on the rate and occurrence of the events were evaluated. Similarity in the age of first appearance of the alcohol-related life problems between the two Mission Indian groups of participants (gender and Native American heritage) was compared by using Spearman’s rank-order correlation (r

s). These same analyses were also performed by comparing the entire Mission Indian sample to published data from COGA

(33). An analysis of how many individuals endorsed individual items, as well as at what age, was evaluated by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square for dichotomous variables. Only analyses (Spearman correlations, ANOVAs, chi-squares) that met criteria for Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons are presented. Variables for demographic and drinking history as well as measures of remission were also analyzed between the groups by using ANOVAs for continuous variables and chi-squares for dichotomous variables. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Overall, the demographic characteristics (mean age=29.8 years, SD=0.5; median income=$28,000, SD=$2,000; proportion unemployed=58%; mean educational attainment=11.0 years, SD=0.1; and family status [single=28%, married or cohabitating=57%, divorced or widowed=9%]) of this sample are similar to available information for the tribe from U.S. Census data

(34). None of the demographic variables significantly differed between men and women or between those with greater than or less than 50% Native American heritage. A total of 243 (60%) of 407 participants met the criteria for a lifetime DSM-III-R diagnosis of alcohol dependence. Men were significantly more likely to be alcohol dependent (N=112, 70%) than women (N=131, 53%) (χ

2=9.76, df=1, p≤0.002). The mean age at onset of alcohol dependence in this group was 20 years, with a significantly earlier age at onset found in men (19.1 years) than in women (20.9 years) (F=6.8, df=1, 241, p≤0.01). Having a native heritage of 50% or greater was associated with having a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol dependence (χ

2=4.99, df=1, p<0.03).

Three life experiences (convulsions, delirium tremens, drinking nonbeverage alcohol) of the original 39 were endorsed by less than 10% of the participants and were dropped from sequential analyses so as not to bias the results considering the small number of respondents endorsing those items.

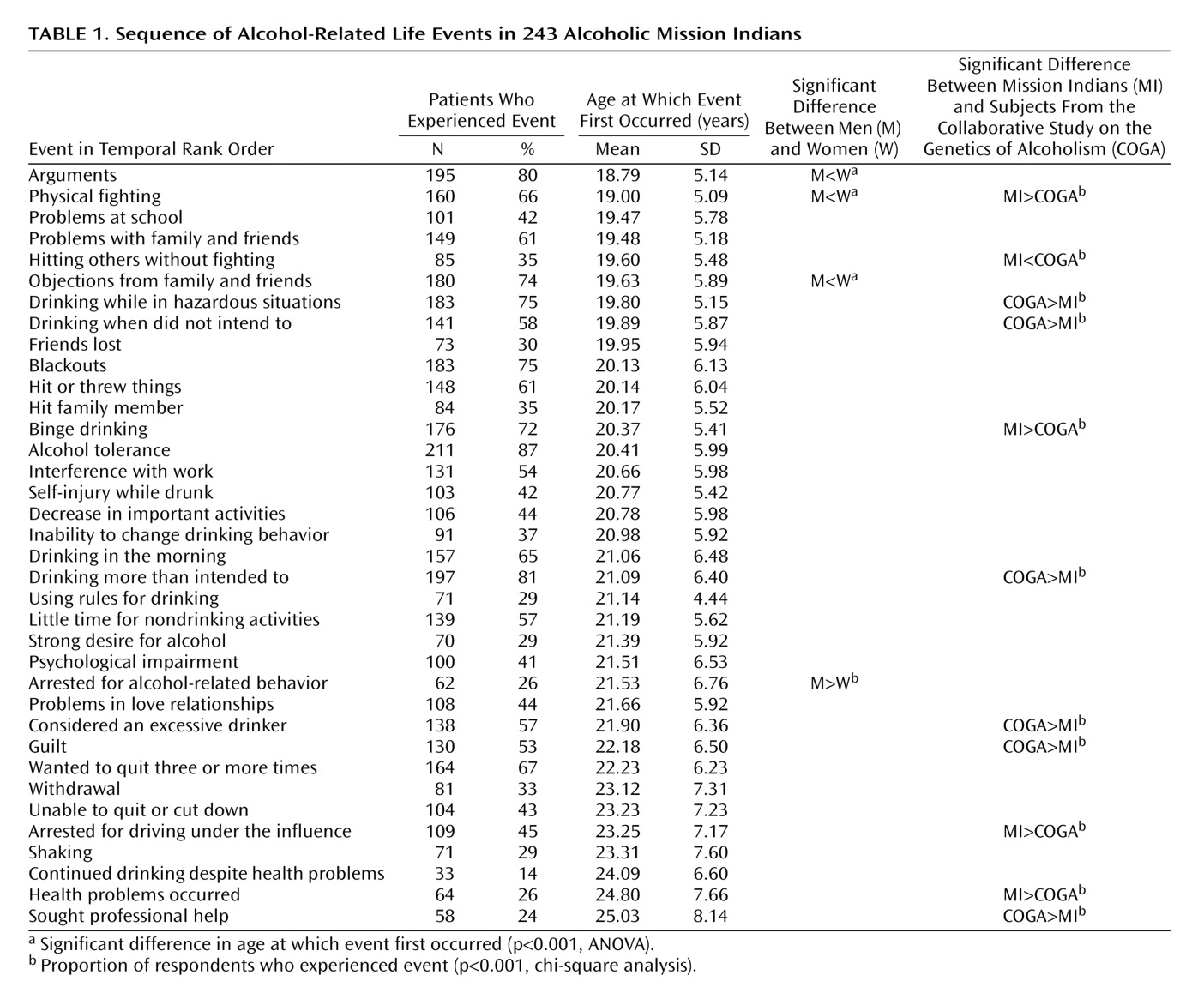

Table 1 presents the retrospective reports of the sequence of 36 alcohol-related life experiences for all of the alcohol-dependent participants in the study. It reveals that alcohol-related job and interpersonal problems, such as arguments, physical fighting, and problems with work or school, friends, or family members, occurred in the participants’ late teens (18–20 years). More physiological events, such as blackouts, the development of tolerance, and self-injury during intoxication, occurred by age 20. Between the ages of 21 and 22, more severe drinking practices, such as morning drinking, feeling the inability to change drinking behavior, and arrests for alcohol-related behavior, were endorsed. By age 24, signs of alcohol withdrawal and alcohol-related health problems were present. Those who sought professional help did so by the mean age of 25.

A comparison of alcohol-related life experiences and their occurrence in time was made between the male and female participants. A high level of similarity was observed between the two sexes in the sequence of the progression of problems (rs=0.75, df=34, p<0.0001). The influence of degree of Native American heritage on alcohol-related life experiences and their first occurrence in time was also made between the participants who had <50% (N=100) and those who had ≥50% (N=143) Native American heritage. A high level of similarity was also observed between the two groups that differed in Native American heritage in the sequence of the progression of alcohol-related life problems (rs=0.86, df=34, p<0.00001).

The exact age at onset and the number of persons endorsing individual items in the progression of alcohol-related life problems were also evaluated for associations with gender and Native American heritage. As shown in

Table 1, the only significant findings were that women had a later actual age at onset of arguments (F=12.1, df=1, 193, p<0.001), physical fighting (F=11.8, df=1, 158, p<0.001), and objections from family and friends (F=14.7, df=1, 178, p<0.00001) than men and were less likely to endorse being arrested for alcohol-related behavior (χ

2=14.4, df=1, p<0.0001). There were no significant differences between the two Native American heritage groups on the proportion endorsing each item or the age at which each event occurred.

To investigate whether the progression of life problems associated with alcohol dependence was different in this group of Mission Indian participants than in individuals participating in the COGA, a comparison was made with data presented in Schuckit et al.

(33). COGA used the same interview instrument used in the present study, the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism, to determine the time course of the development of alcoholism in 478 individuals (317 men and 161 women), 77% of whom were Caucasian, 11% black, 9% Hispanic, and 3% other. The sample included participants who were identified as inpatients for alcoholism treatment as well as those who had never been inpatients; 48% of the sample had never initiated help from a health professional for treatment of their alcohol dependence. The mean age of the COGA sample was 39.4 years, and they had a mean of 13.6 years of schooling; 59% were married, 12% were separated or divorced, and 28% had never married. A high level of similarity was found (r

s=0.88, df=34, p<0.0001) in the progression of alcohol-related life problems when the Mission Indian sample was compared to the COGA data presented by Schuckit et al.

(33).

However, as shown in

Table 1, several differences were found in the proportion of participants endorsing individual alcohol-related items. Mission Indians were significantly more likely to endorse having experienced physical fighting (χ

2=34.7, df=1, p<0.00001), hitting others (χ

2=20.2, df=1, p<0.00001), having drinking binges (χ

2=46.0, df=1, p<0.00001), being arrested for driving while intoxicated (χ

2=15.4, df=1, p<0.0001), and having health problems (χ

2=19.8, df=1, p<0.0001). However, men and women in the COGA sample were more likely than Mission Indians to report that they drank in hazardous situations (χ

2=90.0, df=1, p<0.00001), drank when they had not intended to (χ

2=17.0, df=1, p<0.00001), drank more than they intended to (χ

2=21.2, df=1, p<0.0001), considered themselves excessive drinkers (χ

2=18.7, df=1, p<0.000001), experienced guilt (χ

2=12.5, df=1, p<0.0001), and were more likely to seek professional help (χ

2=62.2, df=1, p<0.0001). No significant differences were found for 25 additional items, including blackouts, shaking, morning drinking, tolerance, psychological impairment, and withdrawal.

To investigate the third aim of the study, the effects of gender and the percent of Native American heritage at remission from dependence symptoms, abstinences, and treatment seeking were studied within the Mission Indian sample. Of the 243 participants with a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol dependence, 61% were in remission at the time of the interview (no symptoms of alcohol dependence for the last 6 months). Participants in remission were significantly older than those who were not in remission (F=16.4, df=1, 242, p<0.0001). The proportion of women in remission at the time of the interview (67%) was also significantly greater than that of men (54%) (χ2=4.4, df=1, p<0.04). Seventy-seven percent of the participants reported having experienced a period of abstinence from drinking lasting 3 months or longer subsequent to having received a diagnosis of alcohol dependence. In this group, the average number of periods of abstinence was 2.7. Fifty-five percent of the abstainers reported two or more abstinence periods. Abstainers were significantly older than participants who had not had periods of abstinence (F=11.4, df=1, 242, p<0.001). Women were more likely to report a period of abstinence lasting 3 months or longer than men (χ2=5.18, df=1, p<0.02). Abstentions and remissions from drinking generally occurred without recourse to treatment. Only 28% of the population had ever been treated for alcoholism either at a clinic or in self-help groups. There were no age differences between the participants who had sought treatment and those who had not. Additionally, no differences were found between men and women in the proportion who had sought treatment. Participants who were ≥50% Native American heritage compared to those who were <50% Native American heritage did not differ on any measures of remission, abstinence, or treatment seeking.

Discussion

To our knowledge, epidemiological studies aimed at determining the rates of alcoholism in American Indian adults nationwide have not been reported. Information on the prevalence of alcoholism, as quantified by interview instruments, has generally been limited to select local communities. Specifically, Robin et al.

(16) reported that in a Southwest Indian tribe rates were 83% in men and 51% in women. In a community sample of Navajo, lifetime rates of alcohol dependence were 70% for men and 30% for women

(35). Rates reported by Kinzie et al.

(36) for a Pacific Northwestern Indian village were given as 73% for men and 33% for women. For a small sample of Cheyenne Indians, lifetime rates of alcoholism were 65% for men and 37% for women

(17). Thus, in the current study of Mission Indian participants, rates of alcohol dependence (70% for men and 50% for women) were well within the range of those reported for other Indian communities.

While it appears that several Indian communities have alcohol-dependence rates that are four to five times higher than those of the general U.S. population, less information is known concerning the nature and course of the disease in Native Americans. Jellinek

(37) described the course and progression of alcohol-related problems according to an orderly sequence but also cautioned that not everyone would experience all of the symptoms in the same sequence over time. Venner and Miller

(38) evaluated 46 alcohol-related life events, described by Jellinek, in a group of 99 Navajo in an alcohol-detoxification center. They found the progression of symptoms in the Navajo sample to be only modestly correlated with other studies of alcoholics and only for men (r=0.48), not for women (r=0.06). Schuckit and colleagues

(21) have argued that the alcohol-related life problems proposed by Jellinek

(37) are limited and difficult to verify and thus developed an instrument to collect data on more objective events. Schuckit et al.

(21,

33,

39) reported a high level of similarity between men and women and within subgroups of alcoholics (inpatients versus outpatients, early onset versus late onset, high versus low social status, etc.) using this instrument (r=0.76–0.96).

High degrees of similarity were also found in the temporal course of alcohol-related life events in Mission Indian men and women. These findings in Mission Indians further support the early notions of Jellinek

(37) and the later findings of Schuckit et al.

(21,

33,

39) that alcoholism has a distinct temporal course that does not appreciably differ between subgroups or, in this case, ethnic heritage. However, some aspects of the course of alcoholism in Mission Indians were found to be different. In the COGA data set presented in Schuckit et al.

(33), 11.3 years elapsed between the onset of alcohol-related problems and seeking help for those problems. In the Mission Indian sample, age at onset of alcohol-related problems was only 1 year earlier, but the time elapsed from the onset of problems to seeking help was 6.3 years. Thus, Mission Indian alcoholism occurs earlier and progresses more rapidly. Similar findings of “telescoping” of the course of alcoholism were reported in a mixed population of Alaska Natives entering alcoholism treatment. In that population, alcoholism also appeared to develop at an early age and progressed over a shortened period of time (7–8 years)

(18).

A comparison of response rates on individual alcohol-related life events between Mission Indian and COGA participants revealed that while overall rates were substantially similar, Mission Indians were significantly more likely to report experiencing binge drinking and health problems. Binge drinking has been reported to be associated with more severe alcohol symptoms as well as social and health consequences in other populations

(40–

42). Mission Indians were also significantly less likely to endorse items such as drinking at times or in amounts that they did not intend to, did not consider themselves to be excessive drinkers, and expressed less feelings of guilt over their drinking than alcoholics in the COGA. One interpretation of these findings is that Mission Indians with a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol dependence feel less “out of control” about their drinking and, in fact, intend to drink the amounts they consume when they want and with less feelings of guilt. However, other aspects of Mission Indian drinking suggest greater disinhibition during intoxication. Mission Indians were significantly more likely to engage in physical fighting, hitting others without fighting while being intoxicated, and being arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol than participants in the COGA.

Native Americans as a whole have a high conviction rate for crimes of violence, and over 90% of all Indian homicides are alcohol related

(6,

43). What is responsible for increased violence during intoxication in some Indian alcoholics is not clear. Physiological measures of cortical disinhibition have been suggested to be associated with familial risk for alcoholism by Begleiter and Porjesz

(44). Some studies have linked these physiological measures of cortical disinhibition to symptoms associated with conduct disorder

(45), including one study in Mission Indian children

(24). However, two separate studies, one in the Navajo and one in Mission Indians, found that alcoholism in those tribes was not associated with an increase in the actual prevalence of conduct disorder

(35,

46). Additionally, the incidence of antisocial personality disorder was found to be similar between Mission Indian alcoholics and alcoholics in the COGA

(33).

Although Mission Indians have high rates of alcoholism (60%), they also have high rates of abstention from drinking (77%) and remission (61%) from alcohol-dependence symptoms, a phenomenon collectively called the “aging-out” process

(10). Fluctuations between periods of heavy problematic drinking, controlled drinking, and abstinence are common occurrences in alcoholics

(47,

48). Schuckit et al.

(49) investigated periods of abstinence following the onset of alcohol dependence in 1,853 men and women and found that 56% had experienced at least one episode. Percentages of alcoholics experiencing periods of abstinence in three smaller studies of alcoholics were found to range from 37% to 60%

(47,

50,

51). In Mission Indians, periods of abstinence and remission generally occurred in the absence of treatment, with only 28% of the participants reporting having ever experienced any modality of treatment, including self-help. Rates of natural recovery or spontaneous remission have been reported to be perhaps 20% or more in some studies of alcohol-dependent individuals

(47,

48). Rates as high as 78% have been reported in surveys investigating natural recovery from an “alcohol problem”

(52). The combination of a high lifetime prevalence of alcoholism and increased rates of remission/abstinence may explain conflicting points of view about drinking in tribes where high lifetime rates of alcoholism and low numbers of current drinkers have been simultaneously observed

(12,

15,

53). Additionally, these data further suggest that programs aimed at prevention of early-onset drinking as well as interventions to promote natural recovery may be beneficial in Native American populations.

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of several other limitations. First, the findings may not generalize to other Native Americans or represent all Mission Indians. Second, the study gathered data on the course of alcoholism using retrospective methods, and more information is needed using longitudinal techniques. Third, comparisons to other large populations of alcoholics may be limited by differences in a host of potential recruitment issues as well as genetic and environmental variables. Despite these limitations, this report represents an important first step in an ongoing investigation to determine risk and protective factors associated with the development of substance use disorders in this high-risk and understudied ethnic group.