Most psychotherapeutic approaches aim to increase the perceptual awareness of emotional processes, to enhance emotional differentiation, and to enable—through insight or cognitive behavioral strategies—new emotional experiences to help overcome dysfunctional mental states. These emotional deficits may be in fact described as alexithymia

(1), focusing primarily on disturbances of affect recognition, affect differentiation, and on the expression of feelings. Although alexithymia was first studied in a variety of medical and psychosomatic disorders

(1,

2), more recent studies have associated alexithymia with dissociation

(3), depression

(1,

4,

5), anxiety disorders, hypochondria, and eating disorders

(1). However, the contribution of alexithymia in interaction with common personality traits to psychopathology has not been investigated systematically. This is important because alexithymia is captured up to 50% by personality models like the five-factor model of personality or Cloninger’s psychobiological model of personality

(6,

7). We hypothesized that disturbances in identifying and differentiating feelings would predict a broad range of psychopathology.

Method

The study group consisted of 254 randomly selected, postacute inpatients and outpatients (156 women and 98 men). All patients were Caucasian and gave written informed consent after receiving full explanation of the study. Patient diagnoses were made according to DSM-IV. The study group comprised subjects with depressive disorders (N=78), anxiety disorders (N=34), obsessive-compulsive disorder (N=28), schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (N=32), borderline personality disorder (N=36), dissociative disorder (N=10), mixed personality disorder (N=18), alcohol dependency (N=9), and somatization disorder (N=9).

Alexithymia was assessed with the German-language translation of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale

(8–

10), which comprised three factors: 1) difficulties identifying feelings, 2) difficulties expressing feelings, and 3) externally orientated thinking. Personality was assessed with the Temperament and Character Inventory

(11,

12), a 240-item, forced-choice, self-report scale. The SCL-90-R

(13), a 90-item self-report scale, was used to assess current psychopathology on nine subscales. All reported scores provided dimensional information, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of alexithymia, a more extreme expression of personality traits, and poorer psychopathology, respectively.

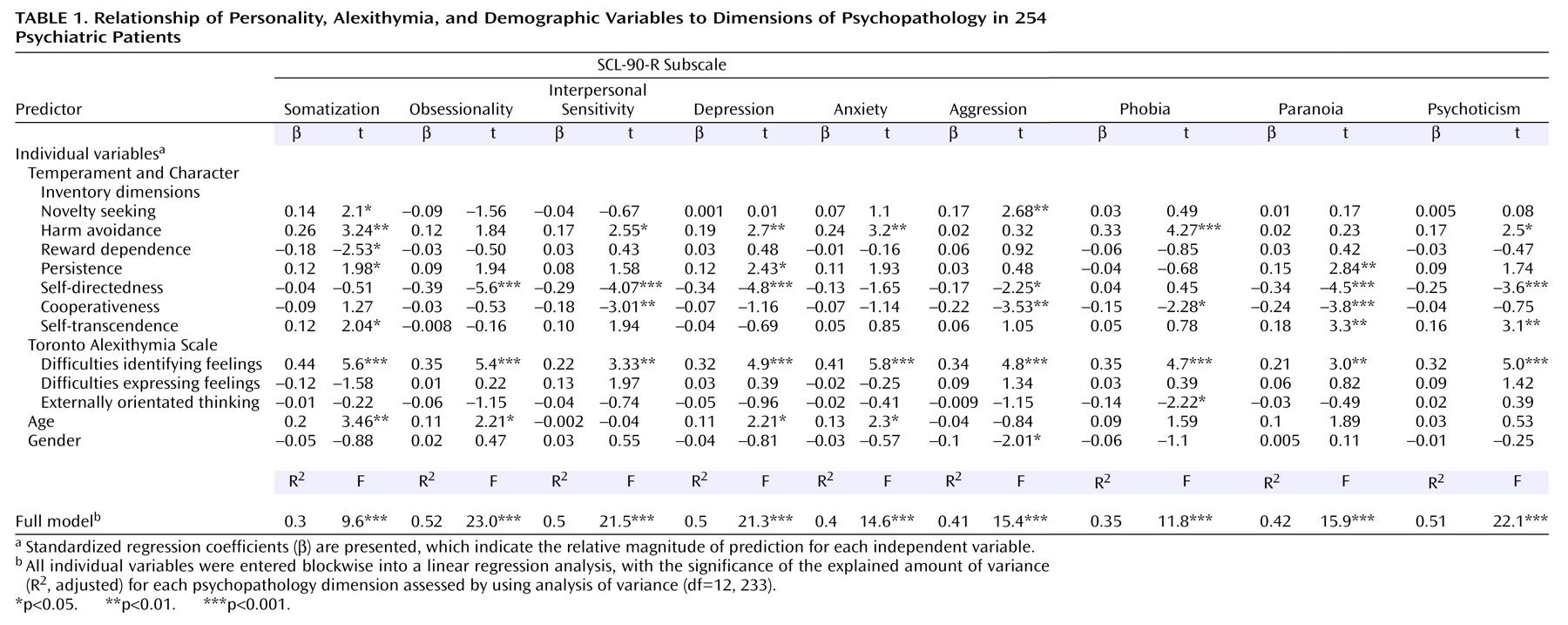

Nine linear regression analyses were calculated using the subscores of the SCL-90-R as dependent variables. The Temperament and Character Inventory dimensions, the Toronto Alexithymia Scale factors, age, and gender were entered blockwise (multivariate) into each of the nine equations as independent variables. The significance of the explained amount of variance (R2) by the regression equation compared with the total variance of the dependent variable was assessed by using analysis of variance. For each independent variable, a standardized regression coefficient (β) is reported, which is based on a prior z transformation of the independent variables. Therefore, β indicates the relative magnitude of prediction of each independent variable. The significance of β was evaluated by a t statistic. All predictor variables had tolerance values >0.4 excluding collinearity.

Results

High scores on difficulties identifying feelings emerged as a major predictor for current psychopathology on all SCL-90-R subscales and were particularly effective in predicting “somatization” (

Table 1). Except for a weak prediction of “phobia” by low externally orientated thinking, none of the SCL-90-R subscales were predicted by difficulties expressing feelings or externally orientated thinking. Gender (male subjects) only emerged as a weak predictor for “aggression.”

Discussion

The results support our hypothesis that the difficulties identifying feelings feature of alexithymia is highly predictive of a broad range of “state” levels of psychopathology, particularly somatization. This leads to the assumption that many mentally ill patients are faced with confusing and strange emotional perceptions that cannot be transformed into meaningful feelings. In contrast, difficulties expressing feelings and externally orientated thinking were almost not predictive for any of the SCL-90-R scores.

The validity of our approach receives support from the fact that distinct and theoretically reasonable patterns of Temperament and Character Inventory dimensions predicted different psychopathological dimensions. A considerable degree of variance (30%–52%) of the SCL-90-R subscales could be explained by the predictors.

Because of the cross-sectional design of our study, we cannot conclude that alexithymia represents a risk factor for the development of mental disorders. However, following the considerations of Taylor and Bagby

(1), we hypothesize that preexisting difficulties in identifying and differentiating feelings predispose someone to emotional dysregulation in stressful situations or relationships, thus creating emotional confusion followed by inadequate behavioral responses. Nevertheless, it seems that dysfunctional psychopathological states additionally alter the ability to cognitively process emotional information

(4). Some studies also suggest that alexithymia is associated with poorer outcome

(1). Therefore, specific psychotherapeutic techniques improving affect differentiation should be evaluated

(1,

14). Besides the necessary replication of our results, further prospective studies should clarify the role of alexithymia as a putative risk factor for mental illness.