Mood disorders are frequently recurrent and are associated with a lifetime risk of suicide that is about 15 times higher than in the general population

(1). There is increasing recognition that strategies for suicide prevention should include improved treatment of mood disorders. Although evidence from randomized trials suggests that drug treatments, including antidepressants and lithium, can substantially reduce the risk of relapse in mood disorders

(2,

3), the effects on suicide are uncertain because the low event rate means that individual randomized trials are invariably underpowered to investigate any potential benefit. On the basis of the existing observational and randomized evidence, however, there have been claims that lithium may substantially reduce the risk of suicide in bipolar disorder

(4). Proposed mechanisms of action include a lowering of risk secondary to a reduction in risk of depressive relapse, a serotonin-mediated reduction in impulsivity or aggressive behavior, and a nonspecific benefit arising from the long-term monitoring provided during lithium therapy

(4). Goodwin and colleagues

(5) recently reported a large observational study from a health maintenance organization that found a 2.7-fold increase in the risk of suicide in patients prescribed divalproex, compared to patients prescribed lithium. Goodwin et al. compared active treatments and so partly controlled for some of the limitations of previous studies, including the possibilities that patients who are able to adhere to long-term lithium treatment may be less disturbed and that nonspecific effects of the close follow-up associated with lithium therapy may reduce the risk of suicide. Nonrandomized studies such as the study of Goodwin et al., however, cannot exclude fully the possibility of confounding by indication, i.e., the decision to prescribe lithium or divalproex may be influenced by other patient factors that, in turn, are associated with suicide risk

(6–

8).

Lithium is a drug with recognized toxicity, and suicide is just one of a number of possible causes of death in patients receiving long-term lithium treatment. It is important, therefore, to consider all-cause mortality, because of the possibility that any possible antisuicidal effect of lithium is offset by increased deaths from other causes.

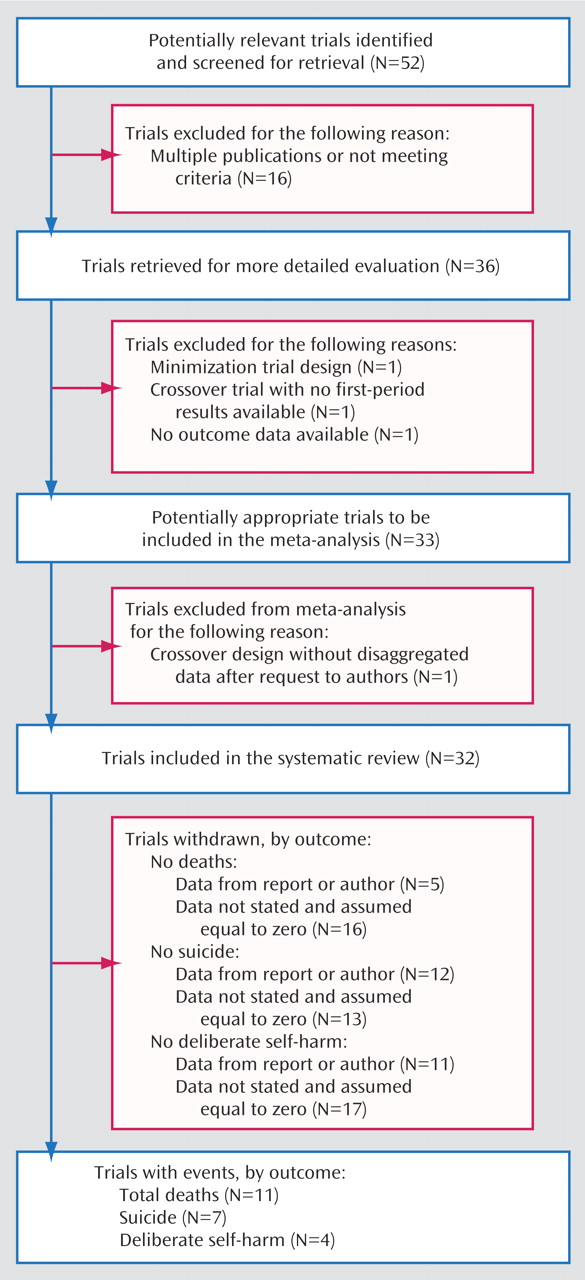

To obtain an unbiased assessment of the potential antisuicidal effect—and the effects on all-cause mortality—of lithium, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence from randomized trials of lithium in patients with mood disorders.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

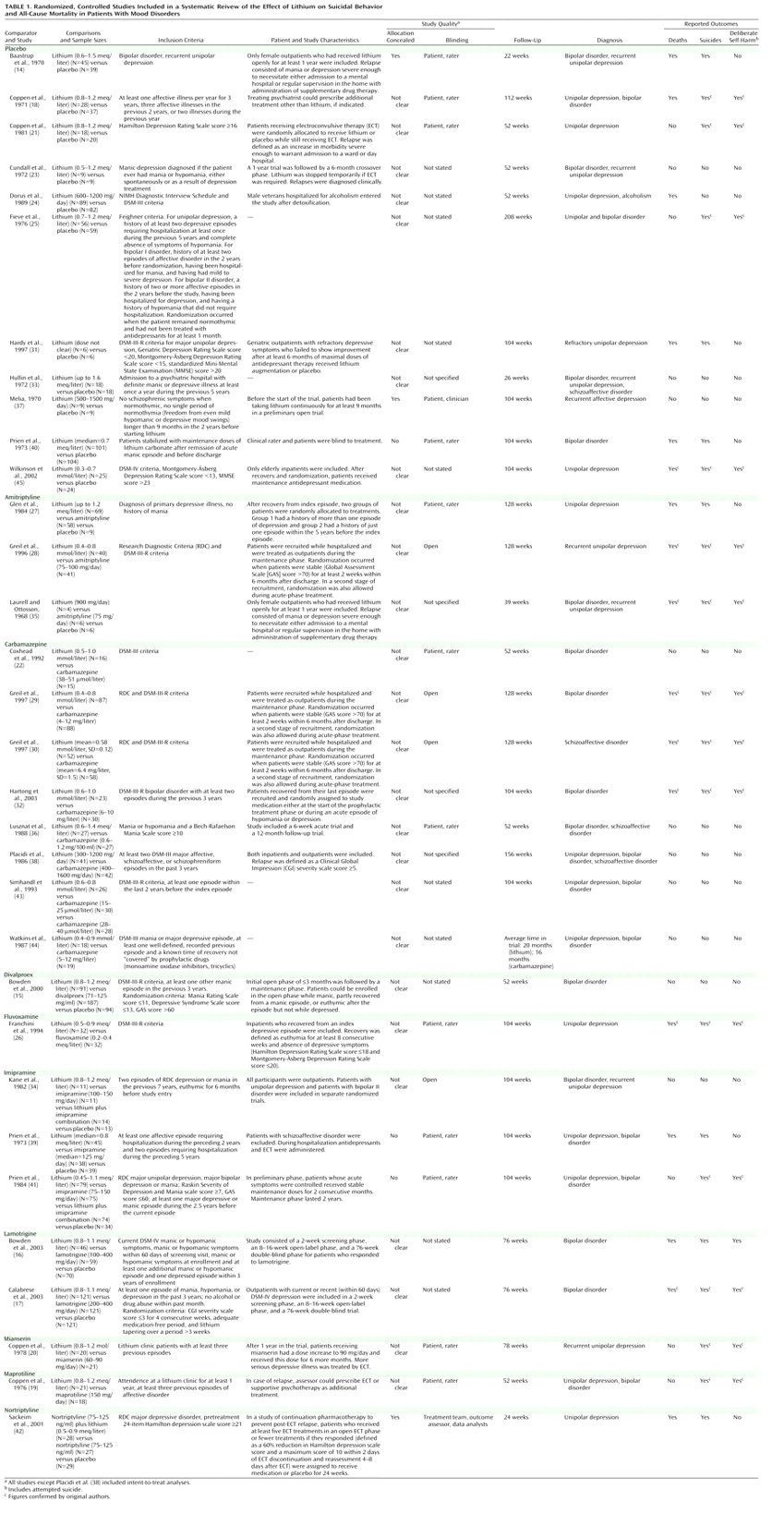

We included randomized, controlled trials comparing lithium with placebo or all other compounds used in long-term treatment for mood disorders (unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, dysthymia, and rapid cycling, diagnosed according to DSM and ICD criteria). We included only long-term treatment (prophylaxis) trials. We arbitrarily defined long-term treatment as treatment with a minimum duration of 3 months.

Search Strategy

We based our search strategy on the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register, incorporating results of group searches of MEDLINE (1966–June 2002), EMBASE (1980–June 2002), CINAHL (1982–March 2001), PsycLIT (1974–June 2002), PSYNDEX (1977–October 1999), and LILACS (1982–March 2001). We used the search term “lithium” and restricted the search from 1999 to 2003. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) was searched with the term “lithium” for new records entered into the database from 1999 to 2003.

To supplement the results from the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register and CENTRAL database, MEDLINE (1999–2003), EMBASE (1999–2003), PsycINFO (1999–2003), and CINAHL (1999–2003) were searched by a librarian using a modified Cochrane randomized, controlled trial filter and the following terms: (lithium or lithium carbonate or calith or camcolit* or carbolit* or ceglution or duralith or durolith or eskalith or hypnorex or hynorex or hyponrex or lentolith or licab or licarb or licarbium or lidin or lilipin or li?liquid or li-liquid or lilitin or limas or liskonum or litarex or lithan or lithane or litheum or lithicarb or lithionate or lithizine or lithobid or lithocarb or lithocap or lithonate or lithosun or lithotabs or litheril or litilent or manialit* or maniprex or phanate or phasal or plenur or priadel or quilonium or quilonorm or quilonum or teralithe or theralite) AND (mood disorders or affective disorders, psychotic or bipolar disorder or cyclothymic disorder or depressive disorder or depression, involutional or dysthymic disorder or seasonal affective disorder or affective disorders or depression, reactive or dysthymic disorder or seasonal affective disorder or affective disorders, psychotic or bipolar disorder or affective disorders or bipolar disorder or cyclothymic personality or major depression or dysthymic disorder or endogenous depression or involutional depression or reactive depression or recurrent depression or treatment resistant depression or seasonal affective disorder or schizoaffective disorder or affective neurosis or depression or dysthymia or involutional depression or manic depressive psychosis or bipolar depression or schizoaffective psychosis or depress* or bipolar or schizoaffective).

In addition, other relevant articles and major textbooks that cover mood disorders were checked. The authors of significant papers, other experts in the field, and pharmaceutical companies that manufacture lithium or the comparator drugs were contacted to identify other relevant published or unpublished randomized, controlled trials.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were suicide, deliberate self-harm (including attempted suicide), and death from all causes in patients randomly assigned to receive lithium or another compound. All-cause mortality was specified as an outcome for several reasons. First, it is free from the variations in both definition and application of the definition that limit the reliability of suicide reports, and it includes deaths from suicide that have not been correctly classified. Second, given the known toxic effects of lithium, any reduction in suicide may be offset by an increase in deaths from other causes, and this possibility would be apparent in the comparison of all-cause mortality rates. Last, all-cause mortality includes suicide plus all other deaths, and the number of deaths from all causes must be at least as large as the number of suicides.

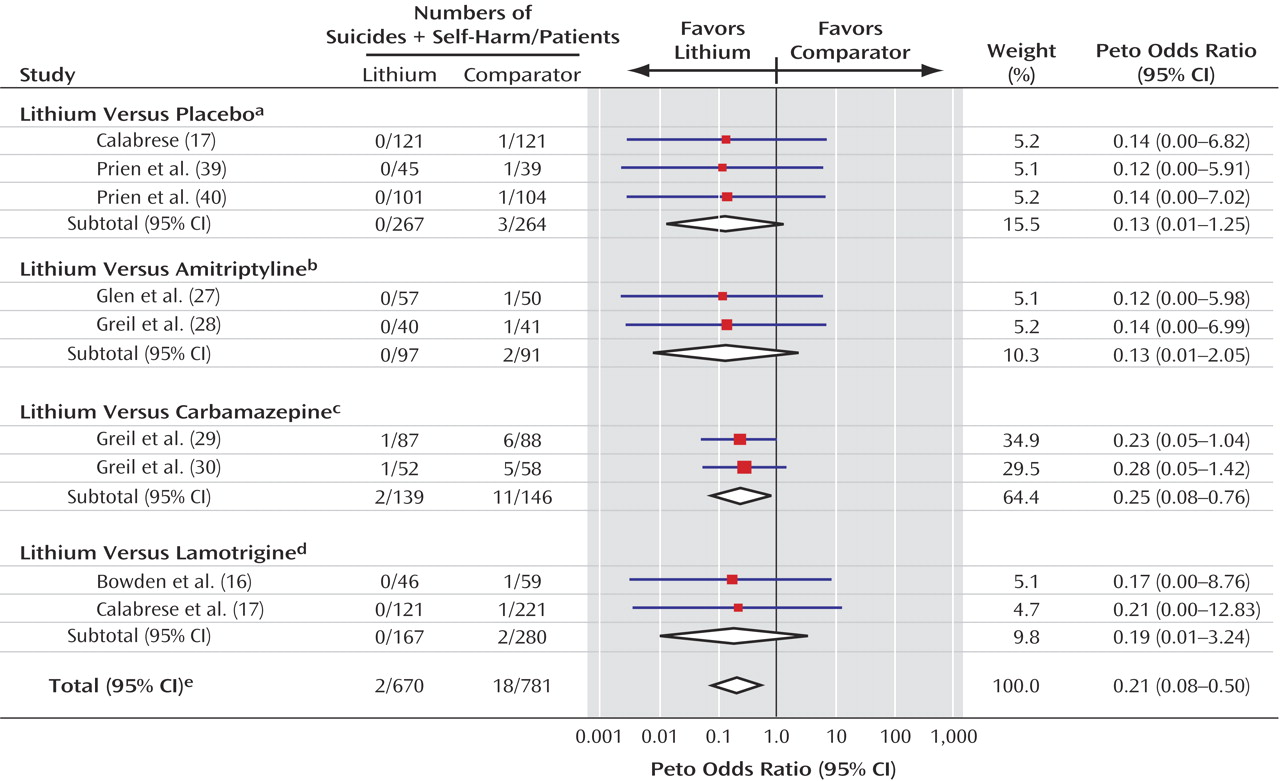

If lithium has a specific action in preventing suicide, one would expect it to also reduce attempted suicide and deliberate self-harm. As suicide occurs too infrequently to be used as a primary outcome in individual clinical trials, use of a composite outcome of suicide plus attempted suicide/self-harm is likely to increase the event rate and, thus, power of the study

(9). For example, a composite outcome of negative events, including suicide and deliberate self-harm, was used as the primary outcome in the recent International Suicide Prevention Trial, which found evidence in favor of clozapine, compared to olanzapine, in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder

(10). We therefore planned, a priori, to investigate a composite of suicide plus episodes of deliberate self-harm.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (A.C. and J.R.G.) independently extracted data; disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third member of the team (K.H.). For each trial we identified inclusion and exclusion criteria, duration of follow-up, diagnosis, doses, and main outcome measures. We assessed the methodological quality of studies according to the criteria of the Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook

(11). Crossover studies were included, but only the first phase of such trials (before crossover) was considered. For trials in which our outcomes of interest were not reported, we attempted to obtain the required data from the original authors.

Data Analysis

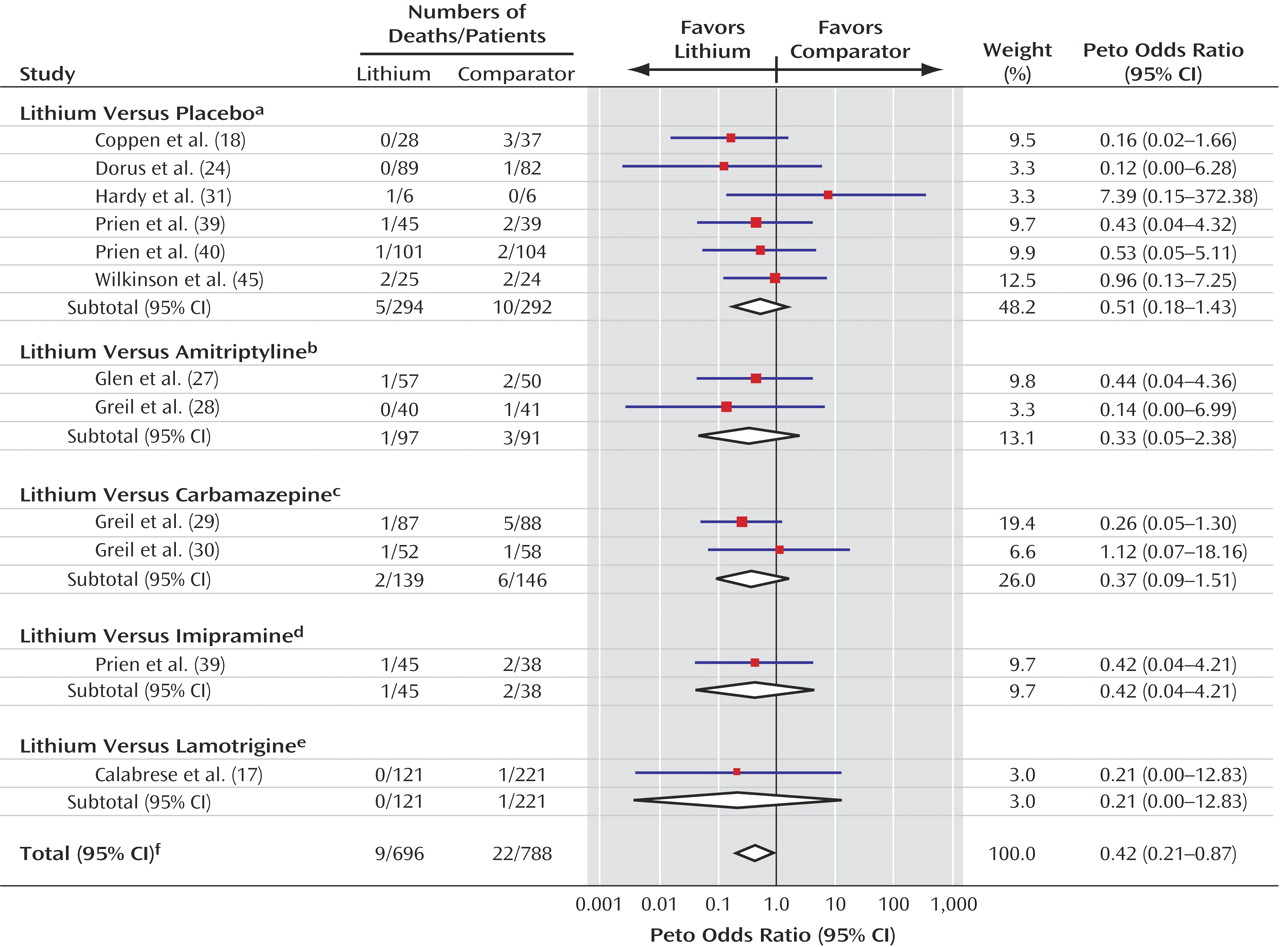

Data from intention-to-treat analyses were used where possible; otherwise endpoint data for trial completers were used. Deaths and self-harm are comparatively rare in clinical trials, and data were sparse. Several trials had no such events in one or more arms. Meta-analysis of sparse data can be problematic, because some methods add continuity corrections to trial arms with zero events, and these corrections may exert a substantial effect on the overall results

(12). Peto’s method was used to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) because this method does not apply continuity corrections and has been shown to be the most reliable method when applied to data on sparse events from studies without extreme imbalances

(12). Trials with no events in any treatment arm were excluded from the analyses because they are uninformative

(12). Sensitivity analyses using other meta-analytic methods were done to assess the robustness of the results. Statistical heterogeneity, in which variation between the results of the individual trials is greater than can be explained by chance alone, was investigated with chi-square tests. Data were analyzed by using the metan routine in Stata

(13).

For trials with more than two arms, we considered each pairwise comparison as if it were separate two-arm trials. For example, if a trial compared lithium with another active drug and with placebo, we included the lithium versus placebo arm and the lithium versus active drug arm as separate trials. This approach included the single lithium group twice in the meta-analysis. We therefore investigated the effect of this double counting by sensitivity analyses that excluded each of the two trials from the pooled analysis.

Discussion

In this review and meta-analysis, we synthesized the available randomized evidence of the effect of lithium on suicide, deliberate self-harm, and all-cause mortality. This work extends the findings of previous reviews because 1) it includes only randomized trials and 2) further data on deaths and causes of death were obtained from the original authors. The effect of lithium on the prevention of symptomatic relapse was not assessed, and the present findings should be considered alongside this evidence, which we reviewed previously for bipolar disorder

(3). As with all quantitative reviews, the current study is subject to a number of limitations. Publication bias—caused by the tendency for trials with negative or neutral findings not to be published—can seriously limit the reliability of meta-analyses

(46). It is possible that trials that failed to demonstrate an advantage for lithium over a comparator are less likely to be published. We consider this possibility particularly unlikely in recent industry-sponsored trials that have included lithium as a comparator, because any design bias in such trials could reasonably be expected to favor the investigational drug

(47). However, because of the small numbers of events and small size of the trials, only one or two moderately sized trials with neutral or negative results could materially affect the estimates.

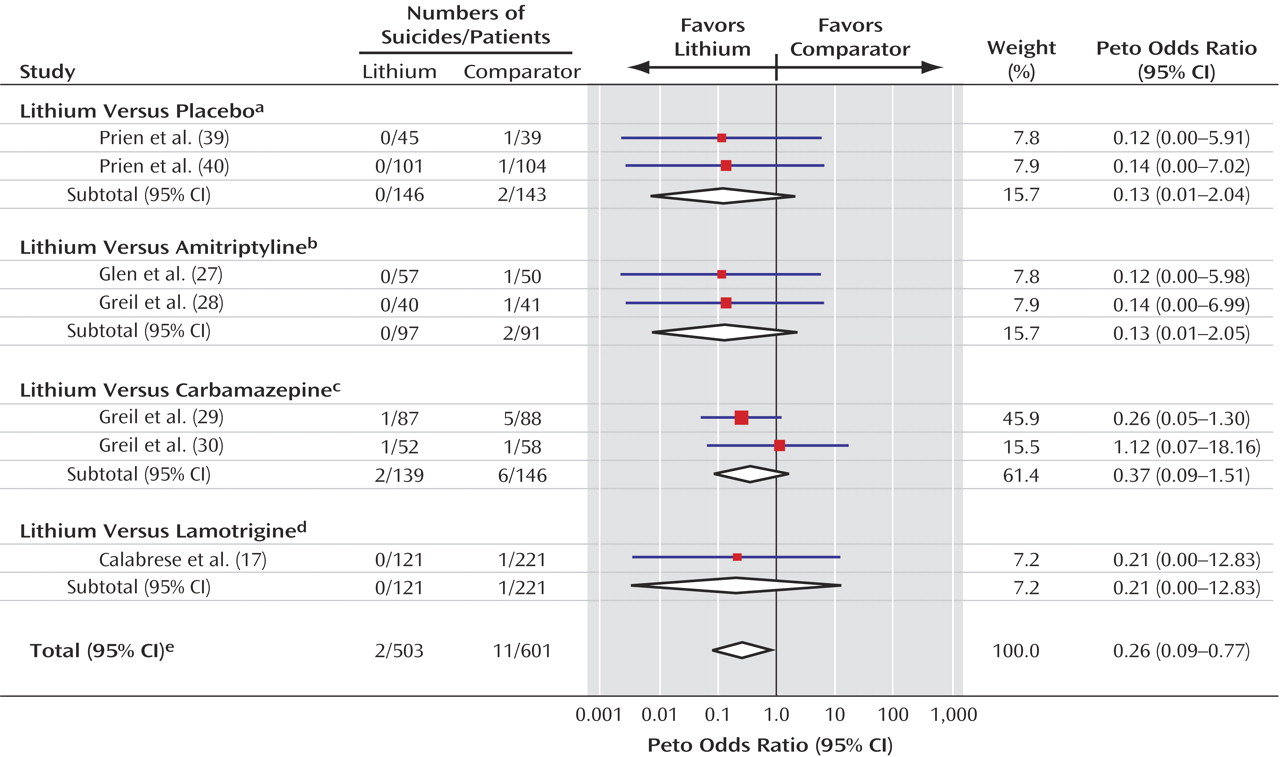

Overall, few deaths from suicide occurred in the trials included in this meta-analysis, which perhaps reflects the fact that patients judged to be at high risk of suicide are not normally recruited to randomized trials. The low numbers of events led to substantial random error and, consequently, unstable estimates of the treatment effect with wide confidence intervals. Thus, the results must be interpreted with caution because the true effect of lithium may be either smaller or greater than we estimated. However, the evidence seems unequivocal that patients treated with lithium were much less likely to die from suicide or from any cause than patients given an alternative to lithium, whether the alternative was placebo or another compound. Lithium appears to reduce the risk of death and suicide by approximately 60% and the risk of a composite of suicide and deliberate self-harm by about 70%. This substantial effect is comparable to that reported in the recent observational study by Goodwin et al.

(5), although it is less than that estimated from previous nonrandomized studies

(4). To our knowledge, this study provides the first demonstration with evidence from randomized trials that any treatment can reduce suicide, specifically, and mortality, in general, in psychiatric disorders.

The trials were clinically heterogeneous in terms of patients, diagnoses, and comparators, and the small numbers of events limited the power of the analysis to detect any interaction between these factors and the treatment effect of lithium. Despite these limitations, the consistency of the results across trials may indicate that the life-preserving effect of lithium is independent of that of the comparator.

Long-term evidence for other agents in the prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder is very limited

(48), and so the results of the current analysis may reflect a general superior efficacy of lithium for the treatment of mood disorder or may reflect a specific antisuicidal property. The consistency of the findings across comparators suggests that lithium prevents suicide rather than that any other drug increases the risk of suicide.

The reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality mainly reflects reduction in risk of suicide, because most of the deaths in the trials were suicides. However, the analysis of all-cause mortality avoids possible ascertainment bias (i.e., events in patients who take lithium may be more or less likely to be classified as suicides) and increases power (because more events are included, and there is less random error). The comparability in the relative risk reduction of both suicide and all-cause mortality also indicates that there was no increase in fatal events due to lithium. The composite of suicide plus deliberate self-harm also showed a similar effect and may be a more feasible primary outcome in future trials. That there were fewer cases of deliberate self-harm than of suicide overall may indicate that data on deliberate self-harm were not recorded systematically in these trials. Given the pattern for suicidal behavior in the general population

(49), the number of patients with deliberate self-harm might be expected to be greater than the number of patients who die by suicide, although this pattern may not be present in the patient population represented in these trials. Clearly, however, if these events are underrecorded, this failure should be rectified in future trials.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis of randomized trials indicates that lithium reduces the risk of suicide in patients with mood disorders. Lithium remains the treatment with the most substantial evidence base for the prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder and should be a first-line therapy for patients with that disorder, including those at risk of suicidal behavior.