The present study included a consecutive series of 670 patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease and mild, moderate, or severe dementia who were assessed with a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation. The main aims of the study were to examine the frequency of major and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease, to determine whether these types of depression have a different functional and psychopathological impact, and to examine whether there is a change in the prevalence of major and minor depression throughout the worsening stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Results

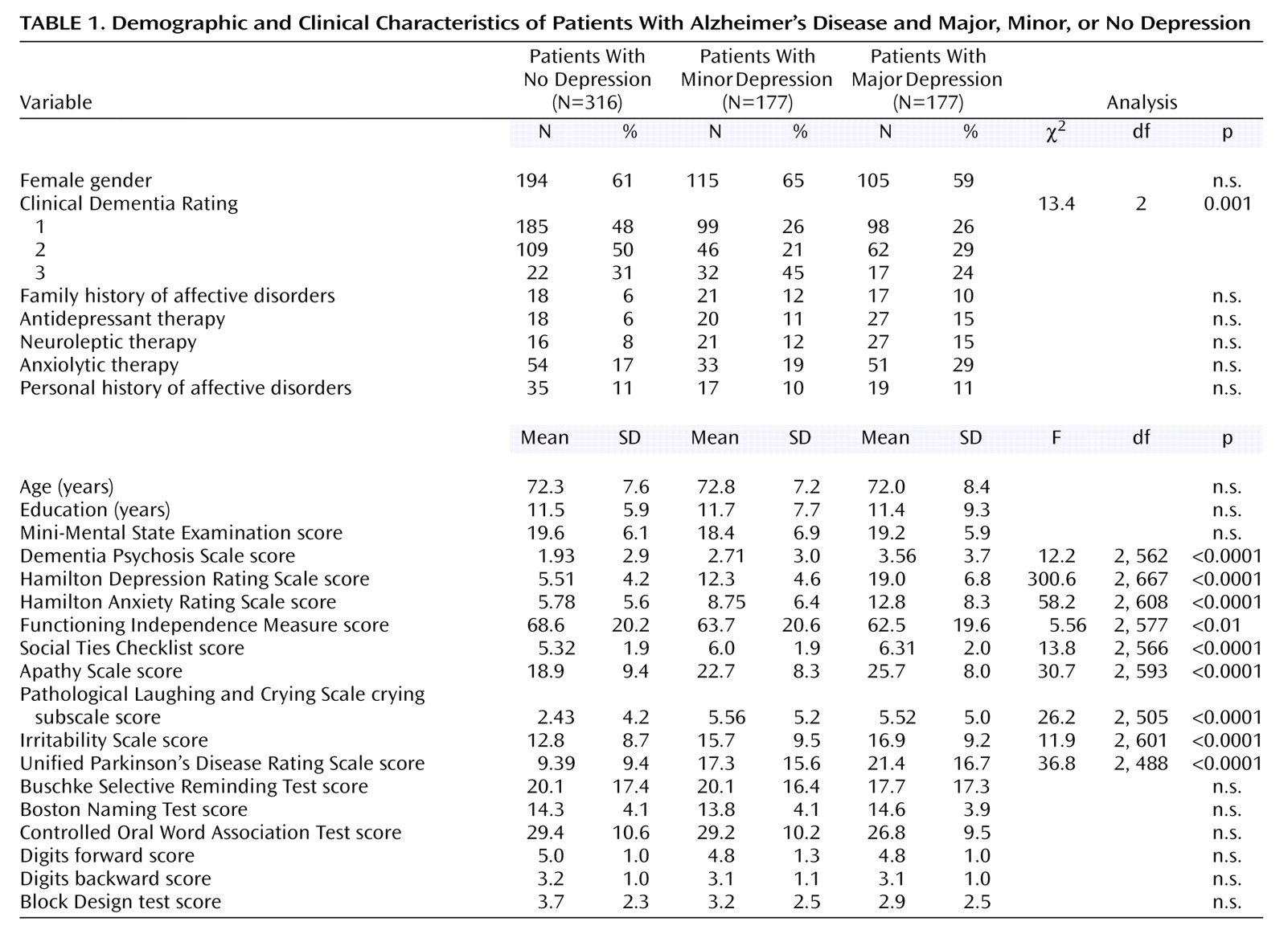

One hundred seventy-seven of the 670 Alzheimer’s disease patients (26%) had major depression, 177 patients (26%) had minor depression, and 316 patients (48%) were not depressed. There were no significant between-group differences in their main demographic characteristics (

Table 1).

Depression and Severity of Alzheimer’s Disease

A hypothesis of unequal frequency of depression based on the stages of Alzheimer’s disease was statistically substantiated (χ2=16.7, df=4, p<0.01). Although the frequency of minor depression increased from 21% (46 of 217 patients) in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease to 45% (32 of 71 patients) in the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease, euthymia declined from 50% (109 of 217 patients) in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease to 31% (22 of 71 patients) in the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease (χ2=14.9, df=1, p<0.0001). Ninety-one percent of the patients (89 of 98) with major depression had a depressed mood in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s disease, 90% (56 of 62 patients) in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease, and 94% (16 of 17 patients) in the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease, indicating that the SCID was applied appropriately in all stages of the illness. Seventy-five percent of the patients (74 of 99) with minor depression and mild Alzheimer’s disease had sad mood (as ascertained by a score of 3 points on the respective SCID item) compared to 76% (35 of 46 patients) in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease and 44% (14 of 32 patients) in the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease (χ2=14.9, df=4, p<0.005). This finding suggests that the patients’ perception of mood may be altered unless the depression itself is severe. The frequency of patients with three symptoms of depression (according to the NIMH criteria for depression in Alzheimer’s disease) but without sad mood was 22% (22 of 100 patients) in mild Alzheimer’s disease, 23% (six of 26 patients) in moderate Alzheimer’s disease, and 41% (13 of 32 patients) in severe Alzheimer’s disease.

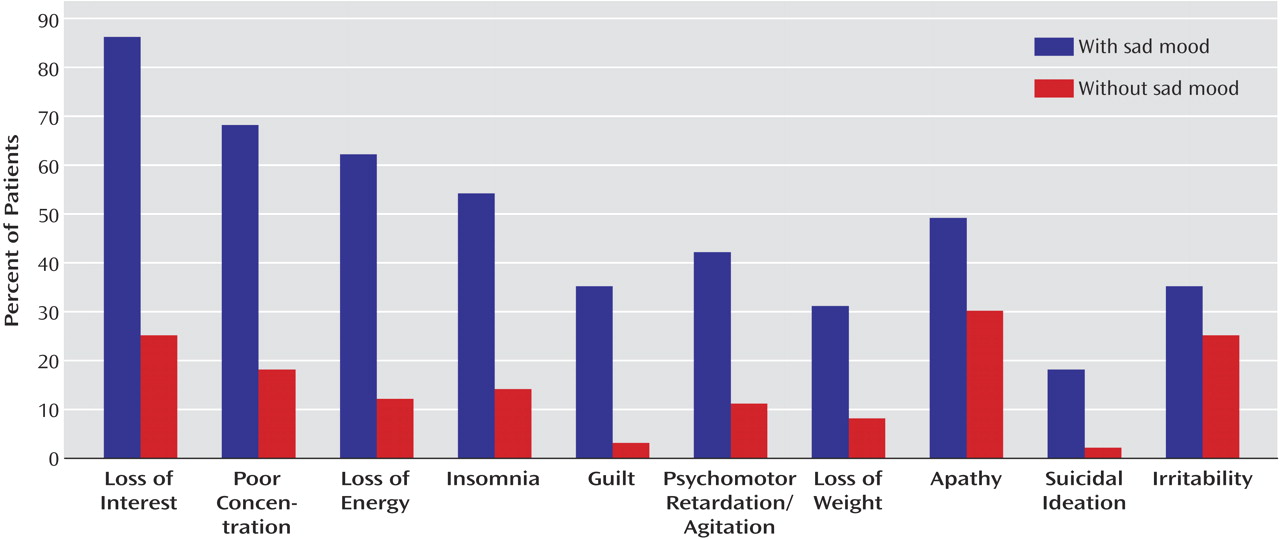

We also examined the association of sad mood with the different DSM-IV criteria for major depression and with the presence of apathy and irritability. Based on the responses to the SCID item rating sad mood, the patients were divided into those without sad mood (i.e., a score of 1 [absent]) (N=262) and those with sad mood (i.e., a score of 3 [threshold]) (N=316). (Patients with a score of 2 [i.e., subthreshold] were not included in this analysis.) (

Figure 1). We calculated a ratio for each DSM-IV criterion of major depression and for the constructs of apathy and irritability using the following formula: percentage positive for patients with sad mood minus percentage positive for patients without sad mood over the sum of both. This ratio was highest (i.e., most strongly associated with sad mood) for guilty ideation (84%), followed by suicidal ideation (80%), loss of energy (68%), insomnia (59%), weight loss (59%), psychomotor retardation/agitation (58%), poor concentration (58%), loss of interest (55%), apathy (24%), and irritability (17%).

Comorbidity of Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease

The frequency of delusions was lowest in Alzheimer’s disease patients without depression and highest in patients with major depression (

Table 1). A similar distribution (i.e., major depression > minor depression > no depression) was found for scores of depression, anxiety, apathy, pathological affective crying, and parkinsonism. The patients with either major or minor depression scored significantly worse than the nondepressed group on the Functioning Independence Measure and the Social Ties Checklist, but there were no significant differences between major depressed patients and minor depressed patients on these variables.

To determine whether the differences observed between the patients with minor depression or no depression resulted from the higher frequency of severe dementia in the group with minor depression, we restricted the analysis to patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease. The patients with minor depression still had significantly worse scores than the nondepressed patients on ratings of depression (Hamilton depression scale score: mean=12.2, SD=4.7, versus mean=5.4, SD=4.1, respectively) (t=13.2, df=437, p<0.0001), anxiety (Hamilton anxiety scale score: mean=8.3, SD=6.3, versus mean=5.7, SD=5.5) (t=398, df=402, p<0.0001), apathy (Apathy Scale score: mean=21.4, SD=8.0, versus mean=18.5, SD=9.1) (t=3.13, df=400, p=0.001), pathological affective crying (Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale score: mean=4.9, SD=5.0, versus mean=2.2, SD=4.1) (t=5.00, df=336, p<0.0001), and parkinsonism (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale score: mean=14.9, SD=13.6, versus mean=8.9, SD=9.0) (t=4.79, df=332, p<0.0001). No significant differences were found on the remaining clinical variables.

Neuropsychological Findings

To avoid floor effects, the statistical analysis included only patients with either mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease (N=599). Eighty-four patients had one or more missing values and had to be excluded from the statistical analysis. A two-way ANCOVA (three groups [major, minor, and not depressed] on scores from six cognitive tests, with MMSE scores as a covariate) showed a significant overall effect (Rao’s R=2.04, df=12, 888, p<0.05). On post hoc comparisons, the patients with major depression had significantly lower scores than the patients with no depression on the Block Design Test (t=3.45, df=380, p<0.001), but there were no significant between-group differences on the remaining neuropsychological variables (

Table 1).

Discussion

We examined the frequency and clinical correlates of major and minor depression in the different stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and there were several important findings. First, the patients meeting the DSM-IV criteria for either minor or major depression had more severe social dysfunction and greater impairment in activities of daily living than the nondepressed Alzheimer’s disease patients. Second, the patients with major depression had more severe anxiety, apathy, delusions, and parkinsonism than the patients with minor depression, suggesting that the severity of psychopathological and neurological impairments in Alzheimer’s disease increases with increasing severity of depression. On the other hand, the patients with major depression or minor depression had similar deficits in activities of daily living and social functioning, suggesting that even mild levels of depression are significantly associated with increased functional impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Finally, the syndrome of minor depression was associated with less mood change in severe compared to mild or moderate stages of Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that the symptoms of depression may change with increasing severity of Alzheimer’s disease.

Before further comments, several limitations of our study should be pointed out. First, 14% of the patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease had to be excluded from the neuropsychological evaluation owing to missing data. However, the proportions of patients with major, minor, or no depression after a full neuropsychological evaluation (26%, 24%, and 50%, respectively) were similar to the proportions of depression in our full study group (27%, 27%, and 46%, respectively). Although all 670 patients were assessed with the SCID, the Hamilton depression scale, and the MMSE, incomplete evaluations resulted from missing data on the remaining instruments, which ranged from 8% for the Hamilton anxiety scale to 26% for the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. However, the proportion of depressed patients who were assessed with the various instruments was similar to the proportion of depressed patients in the full group. Second, our study group consisted of patients attending a dementia clinic at a tertiary care center, which may have biased our findings toward more severe cases. In spite of these limitations, this is, to our knowledge, among the few studies of mood disorders in Alzheimer’s disease to include a large group of consecutive patients and to use structured psychiatric interviews and standardized diagnostic criteria. Third, we have no pathological confirmation of our clinical diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease. However, the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association have been demonstrated to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, all of our patients were assessed with either computerized tomography or MRI, and those with one or more stroke lesions were excluded from the study. Finally, the possibility of pseudodementia in some of our Alzheimer’s disease patients with depression needs to be discussed. In a longitudinal study that used the same diagnostic methods

(25), the authors found that Alzheimer’s disease patients with depression at baseline who were no longer depressed at a follow-up evaluation 18 months later (N=20) had a similar rate of cognitive decline as Alzheimer’s disease patients with depression at baseline who were still depressed at follow-up (N=13). These findings argue against the possibility of pseudodementia in the present study.

One of the main findings of the study was that both minor and major depression had a significant psychopathological and functional impact on Alzheimer’s disease: both groups showed significantly more severe apathy, delusions, anxiety, pathological affective crying, irritability, deficits in activities of daily living, impairments in social functioning, and parkinsonism than Alzheimer’s disease patients without depression. These findings were not explained by differences in age, education, overall cognitive status, or severity of dementia. Major (but not minor) depressed Alzheimer’s disease patients had significantly more severe cognitive deficits than nondepressed Alzheimer’s disease patients, but this finding was of marginal significance. Whether depression produced significant functional impairment, or vice versa, or whether a common factor may increase the likelihood of both depression and functional impairment should be investigated in longitudinal studies.

Forsell and co-workers

(25) suggested that depression may become more frequent as Alzheimer’s disease progresses from mild to moderate dementia and becomes less common in severe dementia. However, in the first study to address minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease in a systematic way, Lyketsos and co-workers

(26) found no significant differences in the frequencies of major and minor depression among the stages of mild, moderate, and severe Alzheimer’s disease. In a recent study, Lopez and co-workers

(27) found that major depression was less frequent in Alzheimer’s disease patients with severe cognitive deficits than in those with mild/moderate cognitive deficits. Our study demonstrated a similar frequency of major depression in the different stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and important methodological differences may explain this discrepancy. We classified patients into mild, moderate, or severe Alzheimer’s disease categories using the Clinical Dementia Rating, whereas Lopez and co-workers

(27) graded the severity of cognitive deficits according to the MMSE. Their finding of a lower frequency of major depression in late Alzheimer’s disease conflicts with their findings of a similar frequency of depressed mood, suicidal ideation, low self-esteem, guilt, episodes of crying, and hopelessness between Alzheimer’s disease patients with mild and moderate/severe Alzheimer’s disease. They also found that sleep problems, anhedonia, and loss of energy were

more frequent in patients with moderate/severe Alzheimer’s disease than in those with mild Alzheimer’s disease.

We followed the DSM-IV provision that depressed mood should be present most of the day, nearly every day, whereas the NIMH criteria do not require the presence of symptoms nearly every day (it is not clear whether this temporal qualification pertains to the symptom of depressed mood only or should also apply to the other symptoms of depression)

(4). The rationale for this change is not clear, and loosening the temporal requirement may substantially decrease the reliability and specificity of the criteria. When patients were diagnosed with the NIMH criteria (i.e., depressed mood or loss of positive affect and at least three additional symptoms of depression), 41% of depressed patients in the stage of severe Alzheimer’s disease had no sad mood, suggesting that the NIMH criteria may have low specificity for depression in the late stages of dementia.

The question also arises as to whether a dimensional or a categorical strategy to diagnose depression should be used in Alzheimer’s disease. Studies of depression in the elderly have demonstrated that subsyndromal depressions might have an adverse functional impact that is sometimes undistinguishable from the negative effects of major depression

(28). Our findings of more severe functional deficits in major depression compared to minor depression and in minor depression compared to no depression seems to fit a dimensional approach. The use of a dimensional strategy, such as establishing a cutoff score on a well-validated scale like the Hamilton depression scale, might detect subthreshold depression that may potentially benefit from early antidepressant treatment. We addressed this question by dividing our group of nondepressed patients into those who had a Hamilton depression scale score of 10 or more (N=41) and those who had Hamilton depression scale score of 9 or less (N=275). The patients with higher Hamilton depression scale scores had evidence of more severe delusional symptoms (Dementia Psychosis Scale—subthreshold depression score: mean=3.4, SD=3.7, versus euthymia score: mean=1.6, SD=3.7, respectively) (t=3.48, df=257, p<0.001), apathy (Apathy Scale score: mean=22.7, SD=8.2, versus mean=18.3, SD=9.4) (t=2.76, df=285, p<0.01), irritability (Irritability Scale score: mean=19.4, SD=8.1, versus mean=11.8, SD=8.3) (t=5.23, df=279, p<0.0001), and pathological affective crying (Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale score: mean=3.7, SD=4.0, versus mean=2.2, SD=4.0) (t=1.98, df=248, p<0.05). However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in activities of daily living or psychosocial adjustment, casting doubt about what is the functional impact of subthreshold depression defined with this dimensional approach.

Another relevant finding was that loss of interest was significantly more frequent among patients with either minor depression or major depression than in nondepressed patients, in contradiction to the NIMH consensus suggestion that loss of interest may not be specific for depression in Alzheimer’s disease. We did not assess decreased positive affect, which replaces the criterion of loss of interest in the NIMH criteria. However, the concept of “positive affect” may be difficult to assess in clinical practice unless clear guidelines are provided, and loss of positive affect could be confused with the blunted affect of apathy or with the loss of facial emotional expression typical of Alzheimer’s disease patients with parkinsonism. In addition, the NIMH criteria do not provide a clear definition of irritability, and this criterion may have low reliability. In a recent study that included 65 patients with Alzheimer’s disease who remitted from a depressive episode during a 3-month follow-up period

(29), we found a significant improvement in all symptoms included in the DSM-IV clinical criteria for a major depressive episode. On the other hand, no improvement was found on scores for irritability, suggesting that depression and irritability are comorbid disorders in Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, in a study that assessed 103 patients with Alzheimer’s disease using the Irritability Scale

(14), we found no significant differences in the frequencies of major and minor depression between Alzheimer’s disease patients with and without irritability. In the present study, the patients with major depression or minor depression had significantly higher scores for irritability than nondepressed patients, but the association between irritability and sad mood was of marginal significance.

Finally, we found that patients with either major depression or minor depression had significantly higher scores on the Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale subscale for crying than nondepressed patients, demonstrating that affective lability is significantly associated with depression in Alzheimer’s disease. The NIMH criteria explicitly exclude affective lability, suggesting that this symptom would be better classified as “affective dysregulation because of dementia.” This suggestion is based on a study that found that the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia item rating “sudden changes in emotion” loaded on a factor of irritability/aggression but not on a factor of depressive features

(30,

31). In a study that used a structured psychiatric interview and a valid instrument to rate the frequency and severity of affective lability in Alzheimer’s disease

(18), we found that 25% of the sample had affective lability with crying episodes, and 81% of this group had either major or dysthymic depression compared to 30% for Alzheimer’s disease patients without affective lability. Important methodological differences may explain our discrepancies with the findings from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. Its assessment of affective lability was based on responses to the item rating “sudden changes in emotion,” and its validity to rate affective lability has not been demonstrated

(30,

31). Our findings suggest that affective lability is not only a frequent symptom in Alzheimer’s disease but may be a useful clinical marker of depression.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the DSM-IV criteria for major depression and minor depression identify clinically relevant syndromes of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Future studies should demonstrate the long-term stability and predictive validity of major depression and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as further explore the relationship of subsyndromal depression and functional impairment.