The participation of patients in medical decisions affecting their treatment is increasingly being advocated in the field of mental health. Treatment guidelines for schizophrenia recommend basing decisions concerning patients’ medication on their preferences and on informed consent; e.g., the National Institute for Clinical Excellence

(1) states, “The choice of antipsychotic drug should be made jointly by the individual and the clinician responsible for treatment based on an informed discussion of the relative benefits of the drugs and their side-effect profiles.” However, little is known as to whether and to what extent patients with schizophrenia want to be involved in making medical decisions and which variables influence this desire. In the present study, the patients’ desire to be involved in medical decisions about their treatment and potential determinants that help to identify patients with a high desire for participation were studied.

Method

This survey reports on baseline data from a current intervention study on shared decision making for inpatients with schizophrenia. This study examines the influence of a decision-aid program for choosing antipsychotic drugs based on patients’ satisfaction, compliance, and rates of relapse. Recruitment was done in 2003–2004 in two German state hospitals and one university hospital. Broad inclusion criteria were used. All patients between 18 and 65 years of age with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-10, F20/F23) who spoke German fluently and who had no diagnosis of mental retardation were eligible for participation in the study. The patients were recruited for the study as soon as their physicians rated them on the conceptual disorganization item of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia

(2) as <5.

To measure the patients’ desire to participate, we used the decision-making preference subscale of the Autonomy Preference Index

(3), a six-item self-report instrument devised to measure the patients’ general wish to participate in making medical decisions (e.g., “The important medical decisions should be made by your doctor, not by you”). Autonomy Preference Index scores range from 0 to 100, with the lowest score (0) corresponding to a desire that the doctor take complete control over medical decisions (paternalistic role of the doctor), whereas a score of 100 means that the patient wants to make all decisions on his or her own (informed choice). Intermediate scores reflect a desire for decision making that is shared equally between doctor and patient

(3). The Autonomy Preference Index was validated and has been used in U.S. primary care patient populations

(3,

4). Internal consistency was reported as alpha=0.82 and test-retest reliability as r=0.84

(3).

We analyzed the following variables of interest that might determine patients’ interest in participating in decision making regarding their treatment:

1.

Factors that are known from the literature to influence patients’ desire to participate (age, gender, education)

(3,

4)2.

Indicators for the chronicity of illness (duration of the illness, number of hospitalizations)

3.

The patients’ experiences (knowledge about the disease, according to a seven-item questionnaire, experiences with present or previous involuntary treatment)

4.

The patients’ attitudes toward treatment (Drug Attitude Inventory, short version

[5]). This scale includes 10 questions on the subjective response to neuroleptic medication, including both positive drug effects (e.g., prevention of relapses) and negative ones (e.g., dysphoric reactions). Higher scores (in a range of 0 to 10) reflect more positive attitudes.

5.

Psychopathology (the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia

[2] total score)

The Autonomy Preference Index score was taken as the dependent variable. First, explorative univariate analyses were carried out for Autonomy Preference Index scores and variables of interest (t tests and Pearson’s correlations [r]). All variables were then entered into a linear regression. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Data from 122 patients were included in the analysis. There were 60 women and 62 men (age: mean=37.6 years, SD=12.1; duration of illness: mean=9.4 years, SD=9.0). Thirty-one patients (26%) were admitted for the first time to a psychiatric hospital; 34 patients (28%) were hospitalized involuntarily. The patients were recruited for the study about 2 weeks after admission to the hospital (mean=16.3 days, SD=20.2, median=9.0). The patients’ desire for participation (Autonomy Preference Index scores) varied between 0 and 91 points (mean=46.6, SD=18.3).

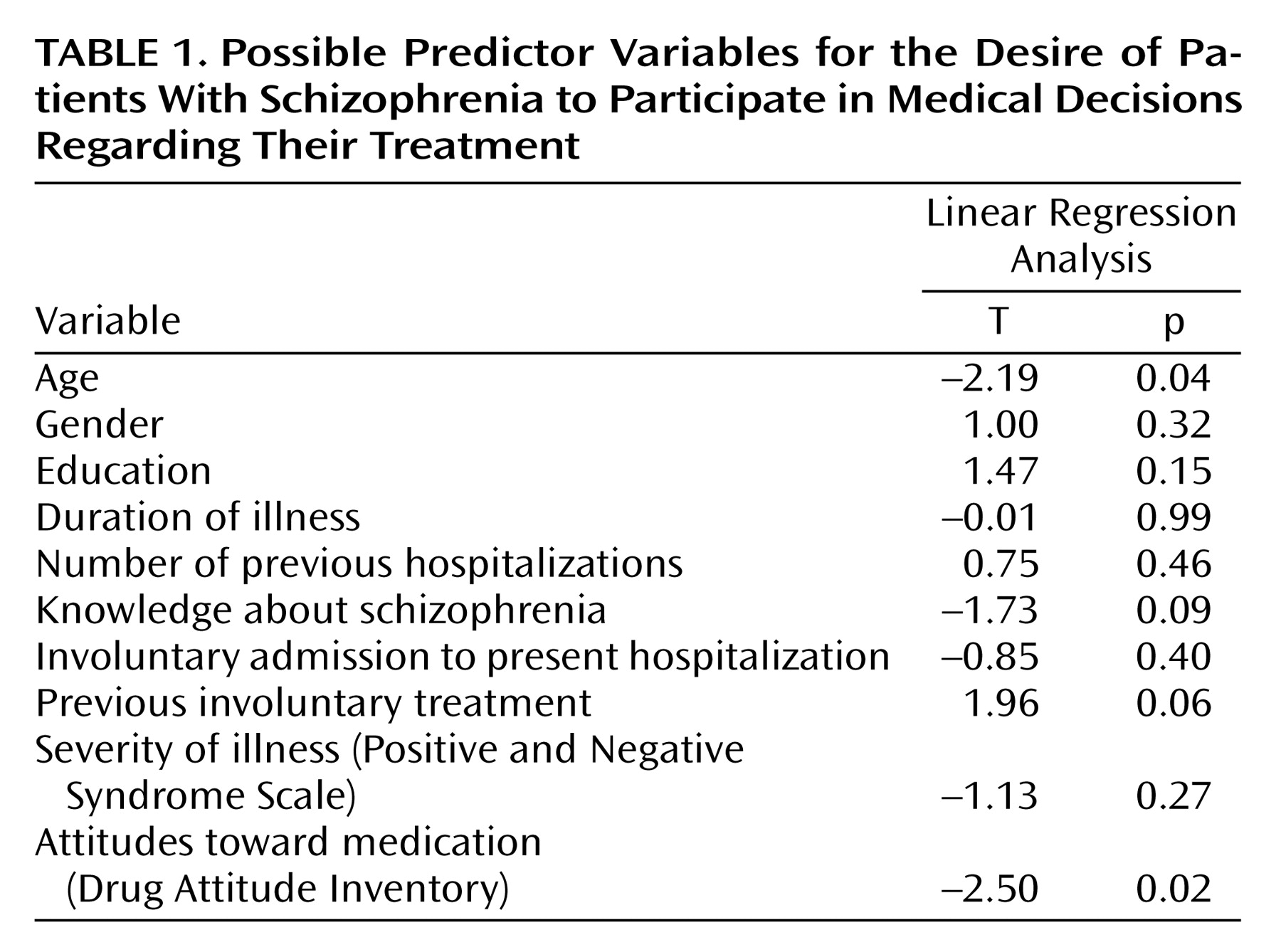

Exploratory tests found no significant correlations between Autonomy Preference Index scores and the variables studied (–0.13≤r≤0.15), with the exception of the patients’ attitudes toward treatment (Drug Attitude Inventory) (r=–0.32, p=0.002). Since intercorrelations between the variables had to be assumed, a linear regression analysis was performed, showing that Drug Attitude Inventory scores and the patients’ ages significantly (R

2=0.42) predicted Autonomy Preference Index scores (

Table 1) when all other variables were accounted for. There tended to be more interest in participation for patients with the experience of involuntary treatment.

Discussion

The patients with the experience of involuntary treatment, those who reported negative attitudes toward medication (according to the Drug Attitude Inventory), and younger patients expressed a higher desire to participate in decision making about their care.

The patients treated involuntarily may be those who deny their illness and want to make autonomous decisions about whether psychiatric treatment as a whole should take place or not. Meeting these patients’ desire to participate is difficult because of legal constraints. However, including these patients in treatment decisions as much as possible may be especially worthwhile because such involvement may improve their attitude toward treatment and thus enhance compliance.

Patients who express their dissatisfaction with their drug treatment, according to Drug Attitude Inventory, might often have legitimate complaints (e.g., dysphoric reactions, side effects) that had up until then been ignored by their physicians for one reason or another. The desire of these patients to participate in treatment decisions should be respected because patients who are not satisfied with treatment are likely to discontinue it. Incorporation of these patients’ views and experiences (e.g., side effects) to a greater extent presumably improves treatment adherence by emphasizing tolerability and consideration of other treatment options (e.g., a drug with a different side effect profile).

One way of including patients in their treatment decisions might be the model of shared decision making

(6), which aims to decrease the informational and power asymmetry between doctors and patients by increasing the patients’ information and control over treatment decisions that affect their well-being

(7).

Overall, the Autonomy Preference Index scores of inpatients with schizophrenia (mean=46, SD=18) were slightly higher than those reported for primary care patients (mean=33–42)

(3,

4). One reason might be the relative youth of the patients in our group because younger age was associated with a higher interest in participation. The fact that schizophrenia is a severe chronic disease and has great influence on the patients’ life is another possible reason why patients are particularly keen on participation.

The mean Autonomy Preference Index score of 46 for inpatients reflects that there is no interest on the patients’ part to take over decisional control completely but rather that patients strongly wish to participate in medical decisions on an equal footing with their doctors.

One limitation of our study was the low internal consistency of the Autonomy Preference Index compared to the validation study (alpha=0.57 versus 0.82, respectively). The reason for this low reliability might be that the Autonomy Preference Index score was determined in nonpsychiatric settings. When we removed the two items that were reversely coded, internal consistency for the remaining four-item scale was satisfactory (alpha=0.71), and results for linear regression analysis were similar (Drug Attitude Inventory scores and patients’ age significantly predicted Autonomy Preference Index scores).

Finally, it is important to note that in the preceding studies

(3,

4), the patients’ desire for information was markedly higher than their desire for participation. Although this was not measured in our study, it might be true of patients with schizophrenia as well and imply that we should adequately inform all patients of their treatment and the various treatment options even when they show no interest in influencing the decisions.

This first approach to studying the desire for participation of inpatients with schizophrenia shows that a wish for active involvement exists and is partly explained by negative attitudes toward neuroleptic medication. Further research on patient information and participation needs, as well as on strategies to meet these needs, is urgently required to improve long-term adherence and thereby treatment results for patients with schizophrenia.