In our research efforts to reduce bullying in elementary schools

(1,

2), we felt it was important to explore whether manifest staff attitudes conducive to bullying may contribute to behavioral difficulties in children. We predicted that teachers who work in schools with high levels of behavioral problems 1) will more commonly endorse attitudes accepting bullying and perceive fewer differences between a hypothetical bullying teacher and a hypothetical nonbullying teacher in terms of behavior and motivation and 2) that more teachers would admit to bullying students and more often report a history of bullying in the course of their own education.

Method

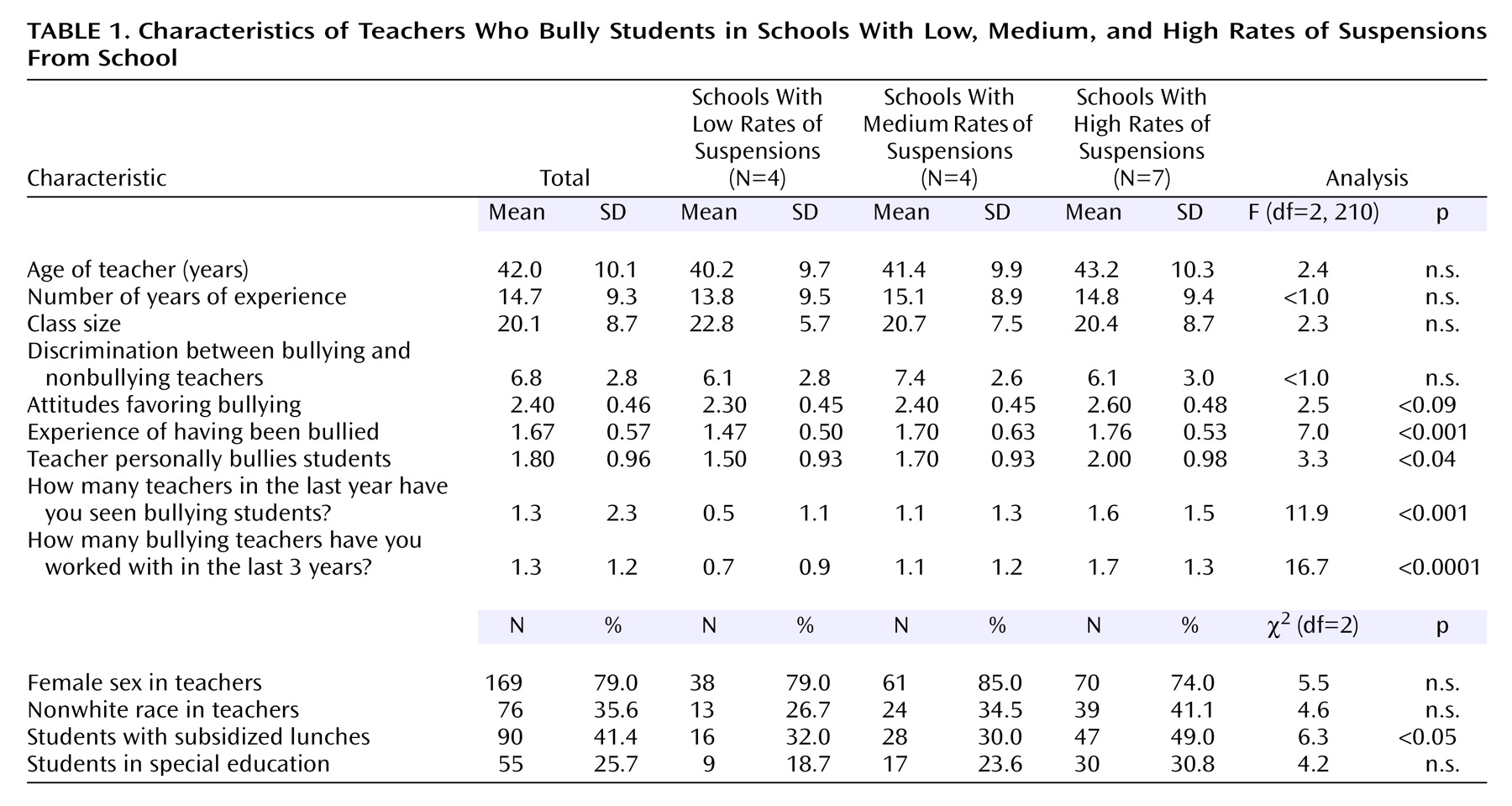

We defined a bullying teacher as one who uses his or her power to punish, manipulate, or disparage a student beyond what would be a reasonable disciplinary procedure. Teachers from a representative sample of relatively demographically homogeneous schools in a Midwestern school district were approached for participation in this study. Anonymous questionnaires were placed in each teacher’s mailbox and were to be delivered to an anonymous drop box. Seventy-five percent of all teachers in eight elementary schools, four middle schools, and three high schools participated (214 teachers from a total student enrollment of 4,034). The schools were grouped into low (two elementary, one middle, and one high school), medium (two elementary, one middle, and one high school), or high (four elementary, one middle, and two high schools) levels of student behavioral problems according to the rates of suspensions from school, as reported for the schools in the sample. The teachers were grouped according to whether they taught at schools with low, medium, or high rates of suspensions. The demographic characteristics of the teachers showed no significant differences in age, gender, or the experience of the teachers, nor did the schools significantly differ in the percentage of minority students, the percentage of students in special education, or class size. Some schools with high rates of suspensions had a somewhat higher percentage of students registered in free lunch programs. We combined these variables into a simple risk indicator and used it as a covariate in univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs).

The questionnaire, available from the first author, covered teachers’ experiences with bullying teachers, their personal experience of bullying students, and the characteristics of bullying and nonbullying teachers rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from never to always. Our previous work

(3) has shown that bullying teachers can be classified into a sadistic type who spitefully humiliate students and hurt their feelings and a bully-victim type who fail to set limits and leave others to solve their problems, i.e., they bully reactively. Test-retest reliability was assessed over 3 weeks with 30 subjects and was in excess of 0.8 across all scales. The two ratings of the characteristics of bullying and nonbullying teachers were subtracted from each other to produce difference scores. The average squared discrepancy across subjects was considered to provide an indication of the extent to which the teachers perceived differences between bullying and nonbullying colleagues. Nine items directly addressed attitudes toward bullying in teachers—e.g., bullying teachers have quiet classrooms, use needless force to discipline students, and put students down to attain order in the classroom—and these were aggregated to yield a single score indicating a favorable attitude toward bullying (Cronbach’s alpha=0.65). ANOVAs were used to contrast teachers’ ratings on continuous variables, and chi-square statistics were applied to categorical variables. All means and percentages are reported in

Table 1.

Results

Our prediction that attitudes favoring bullying would be more characteristic of schools with high or medium, rather than low, rates of suspensions was not confirmed. That is, most teachers did not favor bullying attitudes. Although teachers from schools with high and low rates of suspensions rated bullying and nonbullying teachers similarly, there was a significant difference between the teachers from schools with low and medium rates of suspensions (t=2.3, df=90, p<0.03), with more differences between teachers from schools with medium rates of suspensions and teachers from schools with both high and low rates of suspensions.

ANOVAs showed significant differences between schools with low, medium, and high rates of suspensions on four variables, confirming the remaining predictions. The teachers who reported that they bullied students were more often seen in schools with high rates of suspensions (p<0.04). Teachers who reported having experienced being bullied themselves as students were more often working in schools with high rates of suspensions (p<0.001). Teachers from schools with high rates of suspensions also reported that they had seen other teachers bully students more often over the past year (p<0.001) and had worked with teachers over the past 3 years who had bullied students (p<0.0001) (

Table 1).

Discussion

The study (by matching schools and using covariate techniques) controlled for factors that are often associated with increasing behavioral problems in schools, such as large percentages of minority students and special education students, large class sizes, and fewer years of teacher experience. None of these factors was found to significantly influence the findings. Teachers from schools with high and low rates of suspensions tended to see fewer differences between bullying and nonbullying teachers than teachers in schools with medium rates of suspensions. These findings are consistent with the possibility that teachers in schools with low rates of suspensions have less experience with bullying teachers and that teachers in schools with high rates of suspensions, where bullying teachers are more pervasive, have an eroded sensitivity toward bullying. The higher rates of teacher bullying in schools with more problems suggest either that teachers assimilate to the culture of violence that develops in such schools or that individuals with such predispositions drift toward or are more likely to remain in such institutions because of either preference or lack of opportunities to move to less dysfunctional locations. Because transgenerational transmission of abuse is frequently reported in the literature, it is no surprise that teachers who experienced bullying as children grow up to bully others and are more aware of teachers who bully students. Some teachers may drift toward—or even contribute to—the violent culture of problem schools rather than simply being made more violent by them.

There are obvious methodological limitations to this study. The sample was one of convenience, raising a problem of generalization, but the rates of response of the teachers were gratifyingly high. Although causal inferences cannot be made from these correlational findings and the questionnaire lacks validation, it has good reliability. Nonetheless, the findings represent an initial contribution in an area that is difficult to study.

What can the clinician do about the problem? We know that overly negative, critical, and bullying parental behavior contributes to conduct problems in children and, if challenged therapeutically, can do much to reverse the problems

(4). We have been able to intervene successfully in schools using a model based on changing the responses of adults and children. The rates of suspension from school decreased significantly when these patterns were addressed

(5,

6).