In the last few years, evidence for the efficacy of psychotherapy specific for bipolar disorder is emerging

(1–

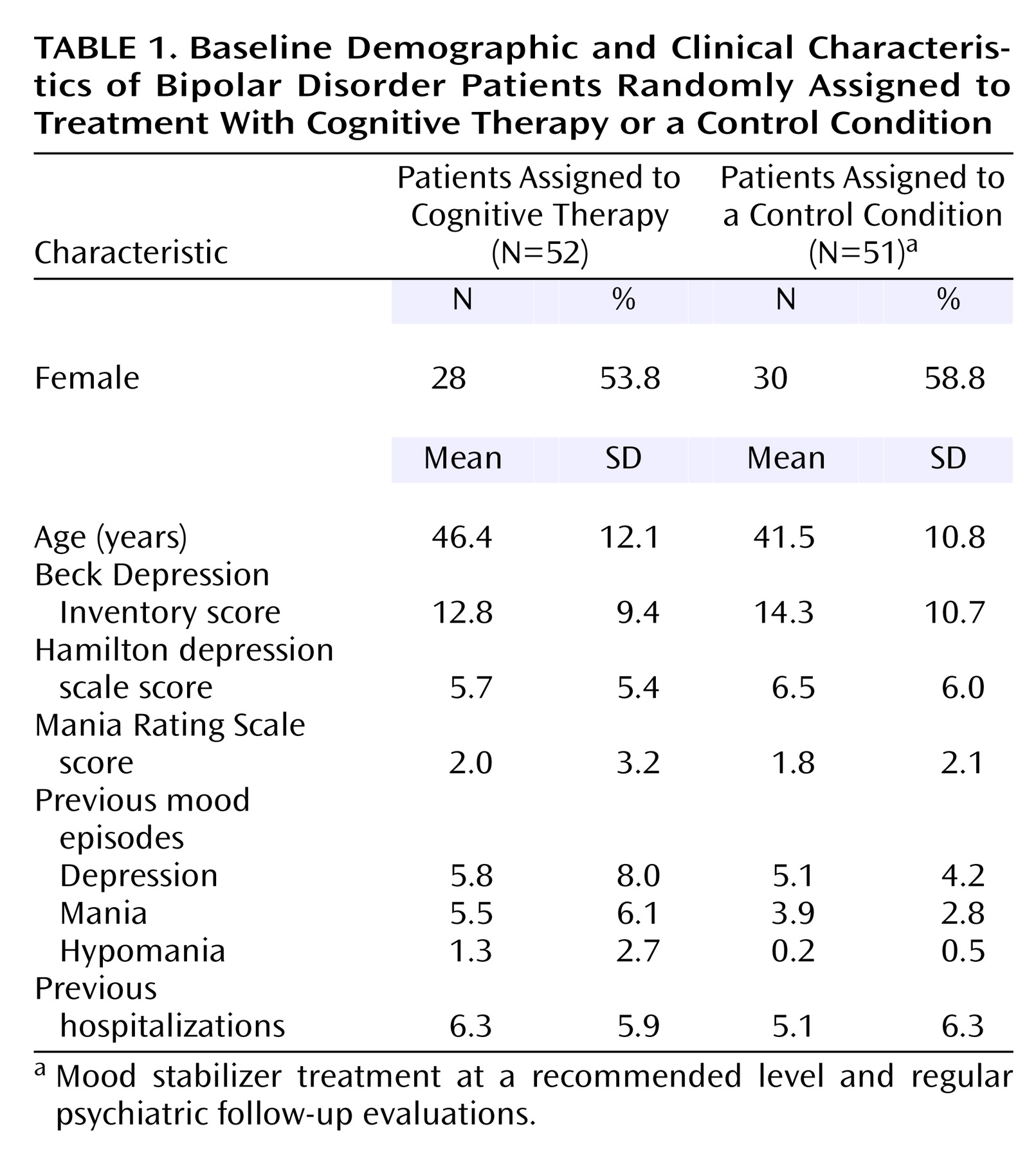

3). We recently reported a randomized controlled study of a relapse prevention approach that showed significant beneficial short-term effects of cognitive therapy for up to 1 year

(4). Over the 12-month period, the cognitive therapy group had significantly fewer bipolar episodes, fewer days in bipolar episodes, and fewer bipolar admissions. The cognitive therapy group also had significantly higher social functioning and showed less mood symptoms on the monthly mood questionnaires. However, given the frequent relapsing nature of bipolar disorder

(5,

6), a longer-term follow-up period is of paramount importance if cognitive therapy is to be a successful form of treatment. Furthermore, cognitive therapy traditionally has a large skill acquisition component. If therapy results in skill acquisition, it should delay or prevent relapses. Hence, a longer-term follow-up period will provide an estimate of the enduring effect of cognitive therapy.

The purpose of this article is to report an additional 18 months of follow-up data for the original treatment trial, resulting in a total of 30 months of data (6 months of treatment and 2 years of follow-up evaluations). Apart from important clinical data such as bipolar episodes, the length of episodes, and social functioning, we also report changes in coping with bipolar prodromes and in cognitive dysfunctional beliefs.

Our secondary hypotheses were that compared with subjects in a control condition, patients assigned to cognitive therapy would have lower depression and mania mood scores and show better medication compliance.

Results

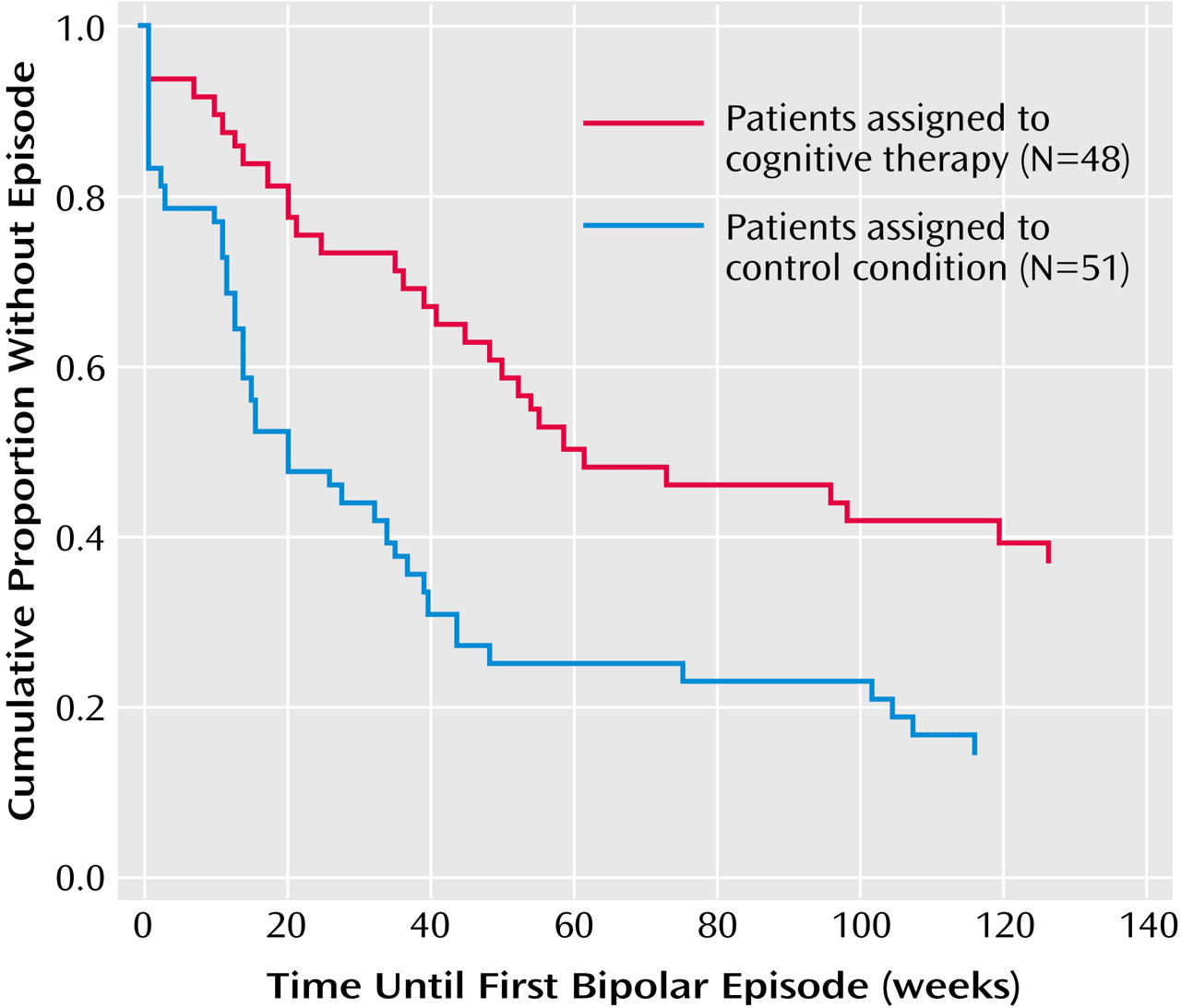

Survival Analysis

Figure 1 depicts the survival curves of the two groups over the 30-month period for bipolar episodes. The actuarial cumulative relapse rates for patients in the cognitive therapy and control conditions, respectively, were 63.8% (N=30 of 47) and 84.3% (N=43 of 51) for bipolar episodes, 50.0% (N=23 of 46) and 67.4% (N=31 of 46) for manic/hypomanic episodes, and 38.6% (N=17 of 44) and 66.7% (N=32 of 48) for depressive episodes. After controlling for the previous number of episodes and medication compliance during the whole 30 months, the between-group differences were significant for bipolar episodes (hazard ratio=0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.29–0.85; p<0.02) and depressive episodes (hazard ratio=0.38, 95% CI=0.19–0.75; p<0.006). However, the difference was not significant for manic/hypomanic episodes (hazard ratio=0.71, 95% CI=0.38–1.35; p=0.30).

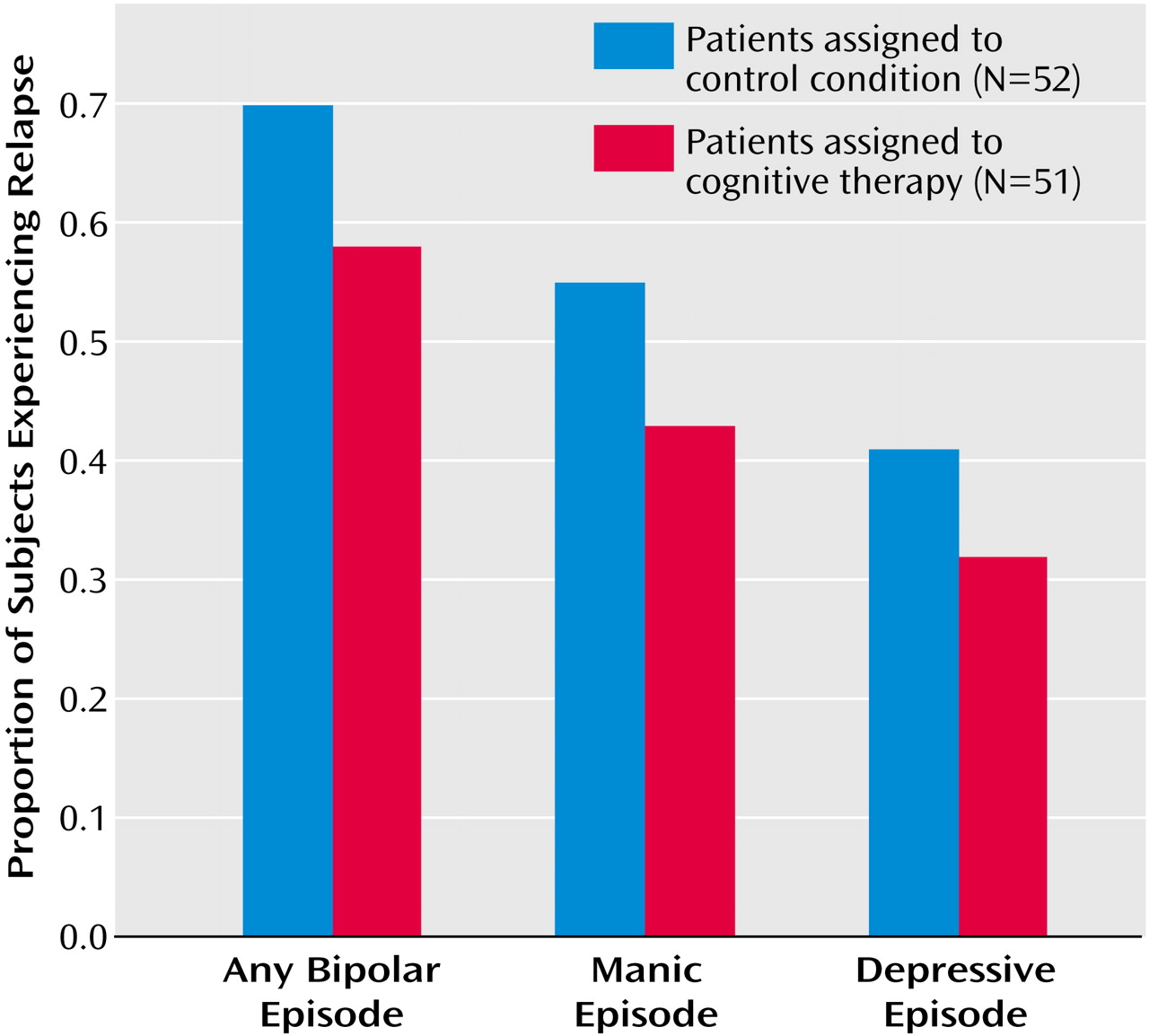

Bipolar Episodes Over the Last 18 Months

Over the 18-month follow-up period, there was a nonsignificant difference between the cognitive therapy and control condition groups in the proportion of subjects who had at least one relapse (57.8% [N=26 of 45] and 69.6% [N=32 of 46], respectively).

Figure 2 depicts the total and type of episodes experienced during the last 18 months of the study for the two groups.

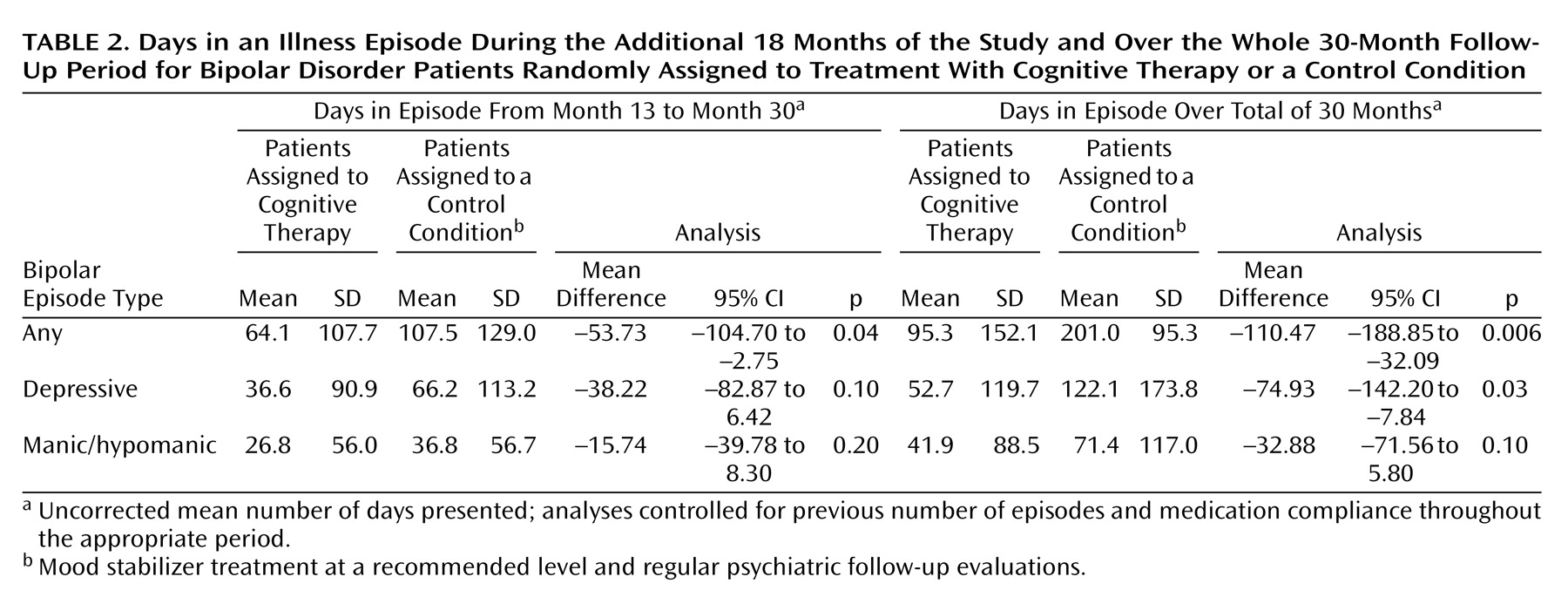

Days in Bipolar Episodes

Table 2 summarizes the mean number of days that patients in the cognitive therapy and the control condition groups were in an illness episode during the additional 18 months of the study and over the whole 30-month follow-up period. During the additional 18 months, after the number of previous episodes and medication compliance over 30 months were controlled, the intent-to-treat analyses showed that the cognitive therapy group had significantly fewer days in bipolar episodes than the control condition group.

Clinical Ratings

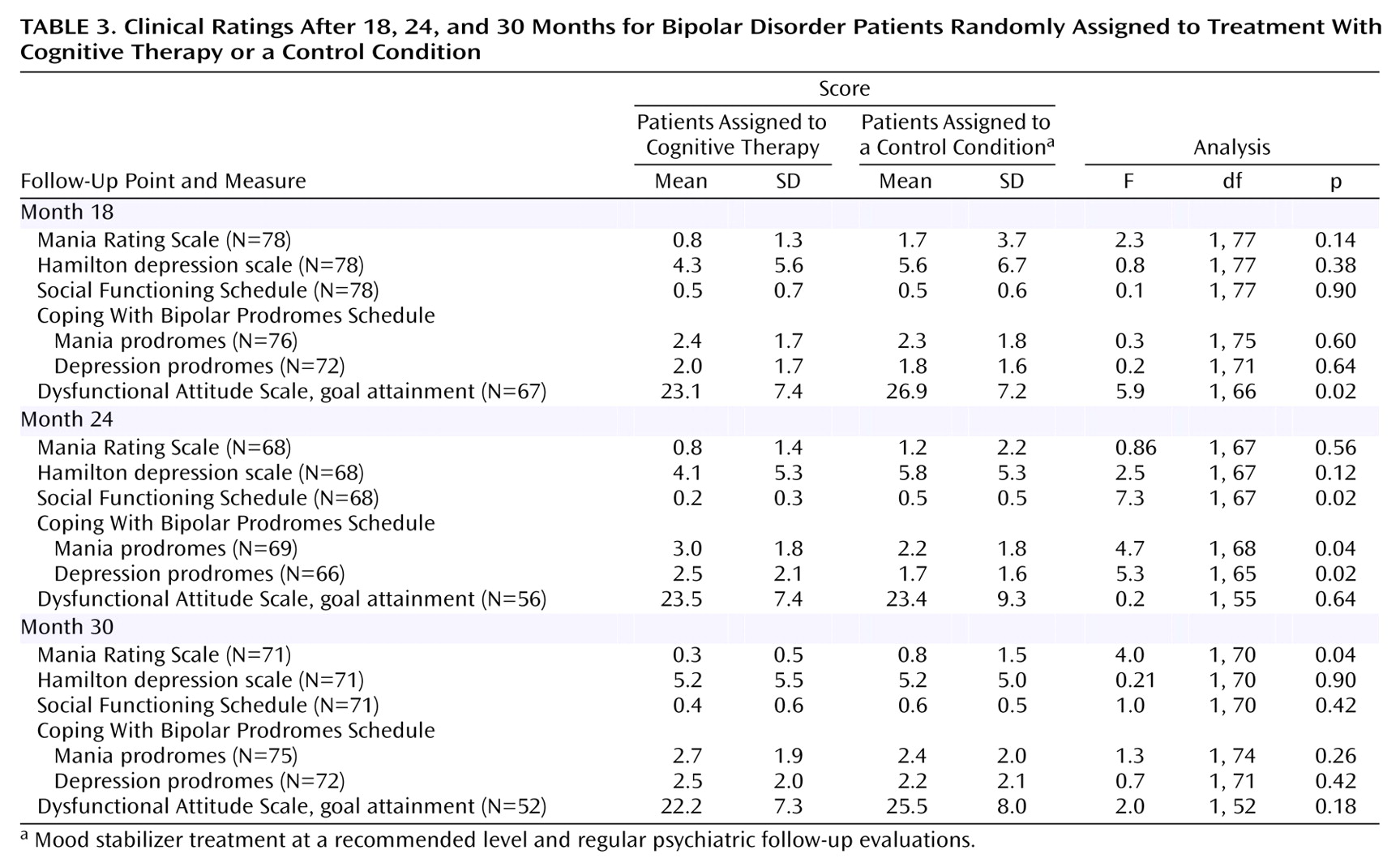

There were significant correlations between the total raw scores of the Social Functioning Schedule and Hamilton depression scale at month 18 (r=0.65, df=77, p<0.02), month 24 (r=0.62, df=67, p<0.02), and month 30 (r=0.53, df=61, p<0.02). Moreover, there were significant correlations between ratings for coping with mania prodromes and total score on the Social Functioning Schedule at month 18 (r=–0.26, df=72, p<0.05), month 24 (r=–0.33, df=67, p<0.02), and month 30 (r=–0.29, df=69, p<0.05). Ratings for coping with depression prodromes and coping with mania prodromes also correlated significantly at month 18 (r=0.68, df=74, p<0.02, two-tailed), month 24 (r=0.71, df=68, p<0.02), and month 30 (r=0.54, df=75, p<0.02).

The scores of the Mania Rating Scale, Hamilton depression scale, Social Functioning Schedule, and Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (goal attainment subscale) and ratings for coping with mania prodromes and coping with depression prodromes at months 18, month 24, and month 30 were analyzed in a MANCOVA to test for differences between the two groups. The scores of these same variables at baseline plus patient reports of medication compliance and number of previous episodes were used as covariates. The omnibus test for group differences was significant (Wilks’s lambda=0.18, f=3.12, df=18, p<0.03).

Table 3 summarizes the results of the univariate tests from the MANCOVA. The cognitive therapy group consistently showed a tendency to perform better than the control condition group at every time point on all six measures. Differences in Dysfunctional Attitude Scale goal attainment at month 18, social functioning at month 24, coping with mania and depression prodromes at month 24, and mania ratings at month 30 reached statistical significance.

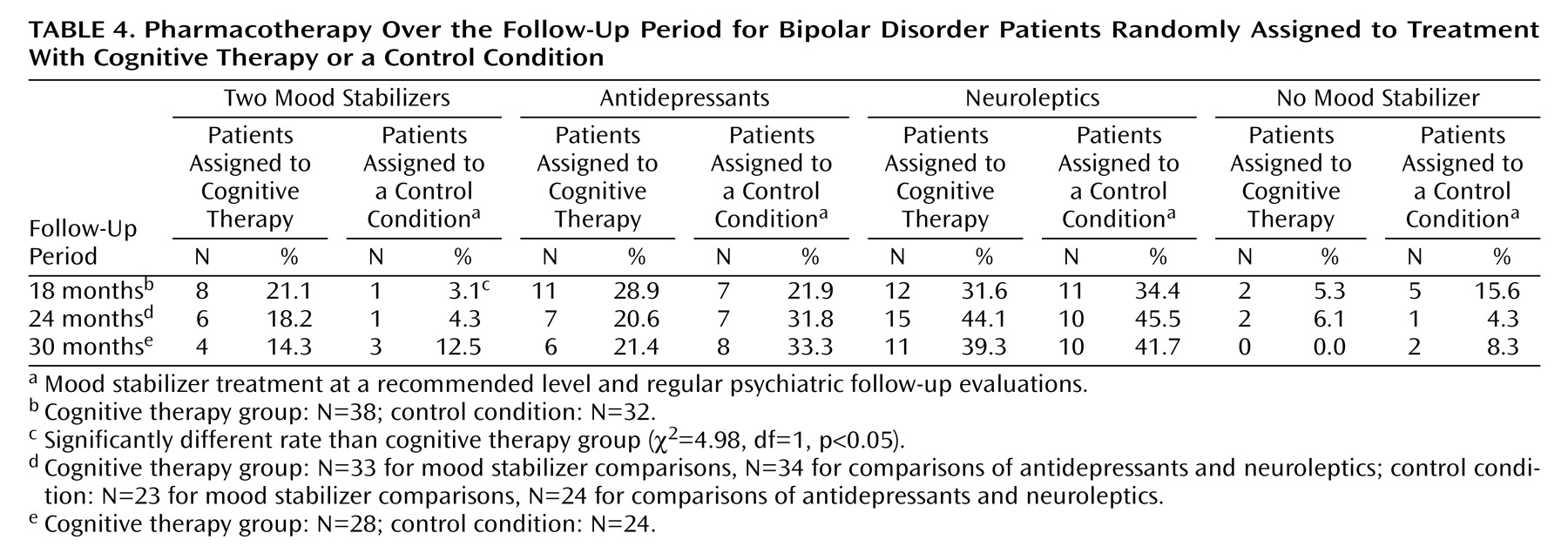

Treatment Variables

Table 4 summarizes the proportion of patients prescribed two mood stabilizers, antidepressants, neuroleptics, or no mood stabilizers. With the exception of two mood stabilizers prescribed at month 18, there were no significant differences between the two groups at any time point. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the dropout rates between patients who were prescribed one or two mood stabilizers or antipsychotics or no antipsychotics at any time point throughout the study.

There was no statistically significant difference in the mean number of psychiatric appointments during the last 18 months (cognitive therapy group: mean=7.2 [SD=5.7]; control condition group: mean=7.4 [SD=7.3]). According to self reports, the cognitive therapy group was significantly more compliant with medication than the control condition group at month 24 (mean=1.4 [SD=0.9] versus 2.2 [SD=1.5], respectively; t=–2.3, df=32.2, p<0.05) and at month 30 (mean=1.5 [SD=0.9] versus 2.2 [SD=1.3]; t=1.9, df=35.3, p<0.05). At month 18 the difference was in the predicted direction but not statistically significant (cognitive therapy group: mean=1.5, SD=0.9; control condition group: mean=1.7, SD=1.2). There was a significant correlation between reports of key workers and patients (r=0.60, df=52, p<0.01).

Discussion

In a previous study

(4), we reported that patients assigned to cognitive therapy fared significantly better than subjects in a control condition in terms of relapse and days in a bipolar episode over the first 12 months of the study. Taking the 30 months as a whole, patients in the cognitive therapy group did significantly better in actuarial cumulative relapse rates than those in the control condition, even when the number of previous episodes and medication compliance were controlled. When the episodes were divided into depression and mania/hypomania, the differences were significant for depression but not for mania/hypomania. This is similar to the initial analysis of Interpersonal Social Rhythm Therapy, which found a significant effect in preventing depression symptoms but not manic symptoms

(5). However, the overall effect of relapse prevention was strongest during the first 12 months of the 30-month study period. This included 6 months of therapy and the following 6 months. There was no evidence that cognitive therapy had a significant effect in preventing relapse over the last 18 months. The effect was less robust as therapy became more distant. Maintenance therapy in cognitive therapy

(15) and interpersonal therapy

(16) has been found to be beneficial in unipolar depression. Our findings suggest that some form of maintenance therapy may be helpful to boost the beneficial effect of cognitive therapy.

However, the number of patients who had suffered from a bipolar episode cannot be the sole outcome measure. The length of bipolar episodes can vary. Bipolar patients can suffer from chronic depression that lasts for months as opposed to short manic episodes that last a couple of weeks. Hence, the duration in which patients are in episodes is an important outcome. As in the first 12 months, the cognitive therapy group had significantly fewer days in bipolar episodes over the last 18 months of the study period.

Patients in the cognitive therapy group performed consistently equal to or better than subjects in the control condition in terms of mood ratings, social functioning, coping with bipolar prodromes, and dysfunctional goal attainment cognition over the last 18 months of the study. The omnibus test for group differences was significant. In our previous report, patients in the cognitive therapy group exhibited significantly better coping strategies for mania and depression prodromes at the end of therapy

(4). In this follow-up study, the cognitive therapy group showed a tendency to report better coping strategies over the last 18 months of the study and significantly better coping with depression and mania prodromes at month 24. Highly driven and extreme goal attainment beliefs were identified as potential vulnerability factors

(7) for extreme goal-pursuing behavior, which would disrupt sleep and daily routines and lead to more episodes. In this study, therapists targeted these attitudes. There was a vigorous attempt to challenge these beliefs, and the cognitive therapy group scored significantly lower in these dysfunctional beliefs at 6 and 18 months.

The beneficial effects for the cognitive therapy group could not be attributed to more frequent psychiatric outpatient appointments and the medication prescribed to patients. There were no significant differences between the two groups in frequency of outpatient appointments. The only difference between the two groups in medication prescribed was that at month 18 significantly more patients in the cognitive therapy group were prescribed two mood stabilizers than patients in the control condition. Both patient and clinician reports suggest that patients in the cognitive therapy group were more compliant with medication than those in the control condition. However, this higher level of compliance or the number of previous episodes may not account entirely for the treatment benefits in the cognitive therapy group, since we controlled for the number of previous episodes and medication compliance throughout the study period for all major outcomes.

There are four limitations of our follow-up study. First, we did not control for the extent of pharmacological or psychological treatment over the follow-up period. Four patients in the control condition received psychological therapy during the follow-up period, although none of the cognitive therapy group received additional psychotherapy. However, the aim of the study was to test the beneficial effects of adding cognitive therapy to a commonly used regimen of pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder patients. Second, there was a lack of control for nonspecific effects of therapy. Hence, we cannot rule out the possibility that the advantageous effect of cognitive therapy was due to attentional effect. Third, the assessment of relapse status was carried out every 6 months. Depression and hypomanic symptoms between the assessments could have been missed. Hence, it was difficult to exclude the possibility that cognitive therapy eliminated bipolar episodes by shifting patients from clinical episodes to more subtle pathological states. Last, we did not measure systematically subjects’ adherence to circadian-rhythm-related routines.

Overall, our study showed that cognitive therapy can prevent relapses in a group of bipolar disorder patients who had experienced frequent relapses despite the prescription of mood stabilizers. Furthermore, there was some evidence that patients who had received therapy had higher social functioning and coped better with bipolar prodromes throughout the study period. Taken together, the findings of this study support the conclusion that cognitive therapy is a worthy addition to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of bipolar affective disorder, particularly for those who suffer from frequent relapses despite the use of mood stabilizers. However, the effect was strongest during the 6 months when patients were receiving cognitive therapy and the 6 months following therapy. As therapy became more distant, the beneficial effect became weaker. Further study should explore the effect of maintenance therapy or booster sessions.