Conclusions

The current study confirms research suggesting elevated rates of suicidal ideation in persons at risk for and diagnosed with Huntington’s disease. It has been suggested that suicide in patients with Huntington’s disease occurs at a rate between seven and 200 times more often than in the general population

(7,

19). Studies of suicide risk and actual completed suicide in Huntington’s disease are encumbered with methodological diversity, however, making comparisons difficult (see Stenager and Stenager

[20] for a review). Autopsy studies have reported suicide rates up to 13%

(12), although the most frequently cited, and average, percentage is 5.7%

(7). In one of the largest studies to date, Almqvist and her colleagues

(21) reported completed suicide rates in a group of 1,817 persons recruited from 100 genetic testing centers from 21 countries. Bird

(22) fluently put these findings into perspective when he compared the suicide rate in Huntington’s disease of 138 of 100,000 persons per year with that of the U.S. population (i.e., 12 to 13 per 100,000 persons

[23]). Not surprisingly, studies assessing suicide risk, rather than completion, report much higher rates and have indicated that suicidal ideation occurs in up to 50% of people with Huntington’s disease

(11,

24–26). Although suicidal ideation is commonly considered one index of suicidal risk, few studies have demonstrated the weight of the various predictors of suicide. Indeed, our current ability to predict actual suicide is poor. Future research should attempt to validate whether suicidal ideation in Huntington’s disease patients is predictive of actual suicide attempts.

Findings from the current study are consistent with, and extend confidence in, the existent research literature. This study used the largest group size ever studied with regard to suicidal ideation in Huntington’s disease. Unlike other large studies, with survey data obtained from family members, our study directly interviewed each individual about current suicidal ideation. There are other aspects of the current study that increase our confidence in the findings. Most notably, this study involves the collaboration of 43 sites in five countries with a standardized interview measure to assess suicidal ideation, a standardized rating scale for clinical features of Huntington’s disease, and a uniform method of disease diagnosis. All study investigators were required to complete training to ensure interrater reliability of the data collection. Finally, the sample studied involves a large number of geographically diverse individuals.

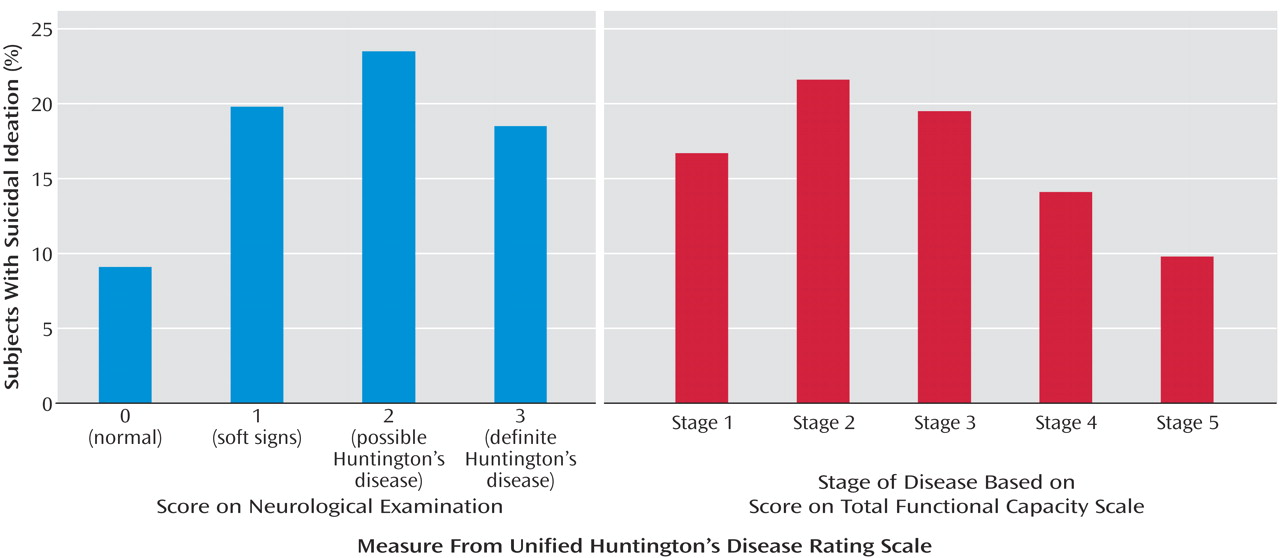

Using suicidal ideation as an index of suicide risk, findings suggest two “critical” periods for increased risk of suicide in Huntington’s disease. First, the proportion of individuals with suicidal ideation more than doubled, from 9.1% in persons at risk for Huntington’s disease with a normal neurological examination to 19.8% in at-risk persons with soft neurological signs. These findings highlight the vulnerability of this particular group of genetically at-risk individuals who begin manifesting signs and experiencing symptoms of Huntington’s disease. The time around the onset of Huntington’s disease has been previously recognized as a time of high risk for suicide. For example, Di Maio and colleagues

(27) compared suicide age and age of disease onset among patients who committed suicide and concluded that suicide may occur at the first appearance of Huntington’s disease symptoms. Similarly, Schoenfeld and colleagues

(12) commented that the prevalence of suicide appears four times higher among suspected Huntington’s disease patients than among those who are diagnosed with definite Huntington’s disease. During the initial onset of symptoms, persons are aware of the course of the illness and are still able to plan and implement a suicide strategy. Further research is needed to characterize the personality, environmental, and biological factors associated with suicidal ideation in presymptomatic Huntington’s disease.

The clinical implications of these findings are great and suggest a major paradigm shift in clinical protocol. There is a widely held belief among clinicians that being given a diagnosis of Huntington’s disease (or other devastating diseases) will worsen depression, instill hopelessness, and increase suicidal ideation. It has been argued that delaying diagnosis of terminal, fatal, and/or devastating disease somehow protects the patient (albeit temporarily) from the trauma of the disease. Our findings suggest that these not-so-uncommon views may be false and that, indeed, the opposite may be true, where the diagnosis reduces the risk of suicide. Contrary to clinical lore, receiving the diagnosis does not seem to be associated with more suicidal ideation. Our findings show that suicidal ideation actually goes down immediately after the diagnosis of Huntington’s disease, suggesting that elevated suicide risk may be associated with the time period before diagnosis, when participants have greater uncertainty about whether they have Huntington’s disease. Perhaps the frequency of suicide may be reduced by the expedient diagnosis of Huntington’s disease combined with appropriate treatment of depression. These findings mandate further discussion and exploration to better guide current clinical practice.

A second critical period for suicide risk in Huntington’s disease occurs in the second stage of disease after diagnosis. Nearly 17% of persons in stage 1 endorsed thoughts of suicide, whereas over 21% indicated having suicidal ideation in stage 2. The second stage of Huntington’s disease is often a difficult time period, where activities may be restricted (i.e., driving, managing finances) and dependence on others for activities of daily living increases. One study examining the proportion of deaths attributed to suicide among individuals diagnosed with Huntington’s disease found that more than half of the suicides occurred in individuals showing early signs of the disease

(12). It can be argued that intentions to terminate one’s life increase when one’s perception of independence dissipates.

The results suggest that certain periods during the progression of disease are associated with increases in the frequency of suicidal ideation in Huntington’s disease. These critical periods include the development of soft neurological signs before a neurological diagnosis and, after diagnosis, the initial progression of the disease, including functional decline. Although the underlying mechanisms of suicide risk in Huntington’s disease are poorly understood, it is beneficial for health care providers to be aware of periods during which patients may experience increased suicidal thoughts. Given the elevated rates of suicidal ideation in Huntington’s disease, it is essential that health care providers regularly screen for suicidal ideation during clinical assessment.

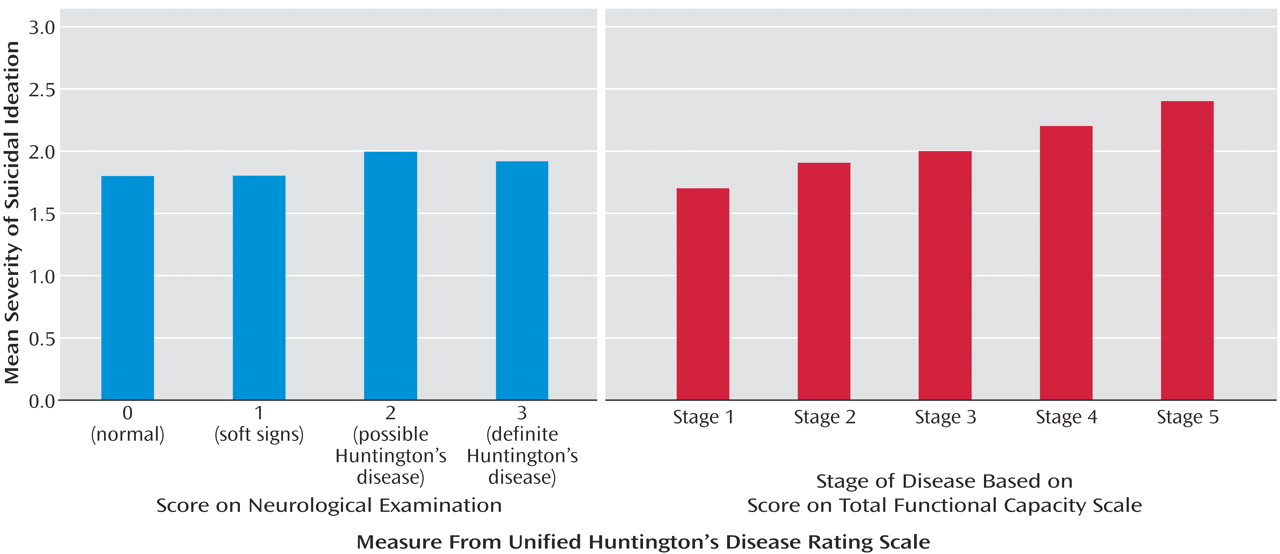

Although our findings suggest that the proportion of persons having suicide ideation diminish with advancing disease, it is striking to note that the severity of suicidal thoughts increased over this same time period. It is difficult to interpret these findings in the context of the current study. One possibility for the findings of decreased proportion with advanced stage of illness may be that people who have already committed suicide are unavailable for study. It is also possible that persons in the later stages of disease are less often queried with regard to suicidal ideation or that they experience decreased verbal fluency, making the assessment of ideation difficult to ascertain. Further research in Huntington’s disease as well as other terminal diseases may offer insight into suicide, its risk factors, and variation with disease course.

The current study has some limitations. Longitudinal study is required to better understand the relationship between suicidal ideation, illness course, and actual suicide attempts. Additionally, future studies should examine the correlates of suicidal ideation in Huntington’s disease so that possible underlying mechanisms for increased suicidal ideation might be established. For instance, it is unknown whether the presence of a major depressive disorder is associated with suicide risk in Huntington’s disease. Although the high prevalence of depression in Huntington’s disease has been well established, the nature of depression and suicidality in Huntington’s disease are poorly understood. It is unknown what proportion of persons with Huntington’s disease experience symptoms of depression secondary to biological changes in the basal ganglia and what proportion of persons are experiencing increased distress secondary to anticipation of a pending event. The interdependence of depression due to neurotransmitter regulation in the brain and depression secondary to life stressors is complex and requires further elaboration. Huntington’s disease may be a good model in which to further study the underlying mechanisms of depression and suicidality. Further research may also require efforts to better separate suicide associated with major depressive disorder from rational suicide in persons with a known terminal illness.

Acknowledgments

Participating investigators and coordinators in the Huntington Study Group were as follows: Phillipa Hedges, Elizabeth McCusker, M.D., Samantha Pearce, and Ronald Trent, Ph.D., Westmead Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; David Abwender, Ph.D., Peter Como, Ph.D., Irenita Gardiner, R.N., Charlyne Hickey, R.N., Elise Kayson, R.N., Karl Kieburtz, M.D., Frederick Marshall, M.D., Nancy Pearson, R.N., Ira Shoulson, M.D., and Carol Zimmerman, R.N., University of Rochester, N.Y.; Elan Louis, M.D., Karen Marder, M.D., Carol Moskowitz, R.N., Carmen Polanco, B.A., Stuart Taylor, M.D., and Naomi Zubin, B.A., Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, New York; Catherine Brown, R.N., Jill Burkeholder, Mark Guttman, M.D., Sandra Russell, Dwight Stewart, M.D., and Jackie Thomson, R.N., Markham Health Center, Toronto; Daniel S. Sax, M.D., and Marie Saint-Hilaire, M.D., Boston University, Boston; Jackie Gray, Cindy Hunter, M.S., Nanette Mercado, Ph.D., Eric Siemers, M.D., and Joanne Wojcieszek, M.D., Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis; Ted Dawson, M.D., Elizabeth Leritz, B.S., Adam Rosenblatt, M.D., Meeia Sherr, R.N., and Candace Young, R.N., Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; Tetsuo Ashizawa, M.D., Jenny Beach, R.N., and Joseph Jankovic, M.D., Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Jeana Jaglin, R.N., and Kathleen Shannon, M.D., Rush Presbyterian/St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago; Anders Lundin, M.D., Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm; Kathleen Francis, M.D., and Kim Lane, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Camden; Alexander Auchus, M.D., J. Timothy Greenamyre, M.D., Steven Hersch, M.D., Randi Jones, Ph.D., and David Olson, M.D., Emory University, Atlanta; Jang-Ho John Cha, M.D., Merit Cudkowicz, M.D., Walter Koroshetz, M.D., Greg Rudolf, Paula Sexton, M.A., and Anne B. Young, M.D., Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Roger Albin, M.D., and Kristine Wernette, R.N., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Donald S. Higgins, M.D., and Carson Reider, M.S., Ohio State University, Columbus; Vicki Hunt, R.N., and Francis Walker, M.D., Bowman Gray School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C.; Robert Hauser, M.D., Juan Sanchez-Ramos, M.D., and Audrey Walker, R.N., University of South Florida, Tampa; Martha Nance, M.D., Minneapolis Veterans Administration Medical Center, Minneapolis; Susan Cleary, R.N., Gina Rohs, and Oksana Suchowersky, M.D., University of Calgary Medical Center, Calgary, Alta., Canada; Kerry Duncan and Lauren Seeberger, M.D., Colorado Neurologic Institute, Englewood; Jody Corey-Bloom, M.D., Michael Swenson, M.D., and Neal Swerdlow, M.D., University of California, San Diego; Henry Paulson, M.D., Ph.D., Robert Rodnitzky, M.D., Lynn Vining, R.N., and Jane Paulsen, Ph.D., University of Iowa, Iowa City; Wayne Martin, M.D., and Marguerite Wieler, B.Sc., P.T., University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alta., Canada; Alicia Facca, M.D., Gustavo Rey, Ph.D., and William Weiner, M.D., University of Miami, Miami; Charles Adler, M.D., John Caviness, M.D., Cindy Lied, R.N., and Stephanie Newman, R.N., Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.; Andrew Feigin, M.D., and Jennifer Mazurkiewicz, B.A., North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, N.Y.; Karen Caplan, M.S.W., Janet Cellar, R.N., and Kenneth Marek, M.D., Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.; Michael Hayden, M.D., Lynn Raymond, M.D., and Gina Rohs, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Leon S. Dure, M.D., and Jane Lane, R.N., Children’s Hospital of Alabama, Birmingham; Diane Brown, R.N., Stewart Factor, D.O., and Eric Molho, M.D., Albany Medical College, Albany, N.Y.; Madeline Harrison, M.D., Carol Manning, Ph.D., and Elke Rost-Ruffner, R.N., University of Virginia, Charlottesville; Jonelle Adams, Ruth Cummings, R.N., and Vicki Wheelock, M.D., University of California, Davis; Richard Dubinsky, M.D., and Carolyn Gray, R.N., University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City; Ann Catherine Bachoud-Levi, M.D., Hôpital Henri Mondor, Creteil, France; Hartmut Meierkord, M.D., Universitatsklinikum Charite, Berlin; Joseph Friedman, M.D., and Margaret Lannon, R.N., Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket; Joan Lawrence, M.D., Royal Brisbane Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; and Allen Rubin, M.D., and Rose Schwarz, R.N., Allegheny University, Philadelphia. The biostatistics and coordination center staff were as follows: Alicia Brocht, B.A., Kathy Claude, M.S., Joshua Goldstein, Michael McDermott, Ph.D., and David Oakes, Ph.D., University of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y.