Rates of suicide are elevated in patients with chronic conditions, including, for example, cancer (

1,

2), diseases of the CNS such as multiple sclerosis (

3), and HIV infection. A recent study of HIV-infected patients in several U.S. cities found that about one-fifth of patients reported suicide ideation in the previous week (

4). Before the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), it had been shown repeatedly that patients with HIV infection are more likely to die by suicide than are HIV-negative individuals (

5,

6). This is not surprising, considering the bleak prognosis of HIV infection and AIDS in the pre-HAART era. Stigma, discrimination, and social isolation may also contribute to elevated suicide rates, and anxiety and depression are common in HIV-infected patients (

7,

8). Substance abuse is also frequent in this population and has been shown to be related to suicide (

9).

The introduction of HAART in 1996 has led to a substantial reduction in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality (

10,

11). Given the improved prognosis for patients with HIV infection, one might expect lower suicide rates in the HAART era. HAART is not a cure, however, and it is associated with adverse effects, including mood disorders (

12) and other effects that could lead to suicidal ideation (

4). A recent study comparing treatment changes in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and two cohorts in Cape Town, South Africa, has shown that in both settings the most frequent reason to change therapy was toxicity (

13), although changes due to toxicity occurred twice as often in Switzerland, where many more drug options are available. This and other studies (

14,

15) suggest that toxicity is a major burden that impairs quality of life.

It is unclear whether and to what extent HAART has affected suicide rates. It is also unclear to what extent suicides in HIV-infected patients are associated with diagnosed and treated conditions such as depression. Finally, rates of suicide in HIV-infected patients may be affected by factors not related to HIV infection, that is, by trends in the general population. We analyzed time trends and risk factors for suicide in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and compared them with trends and risk factors in the general population of Switzerland.

Discussion

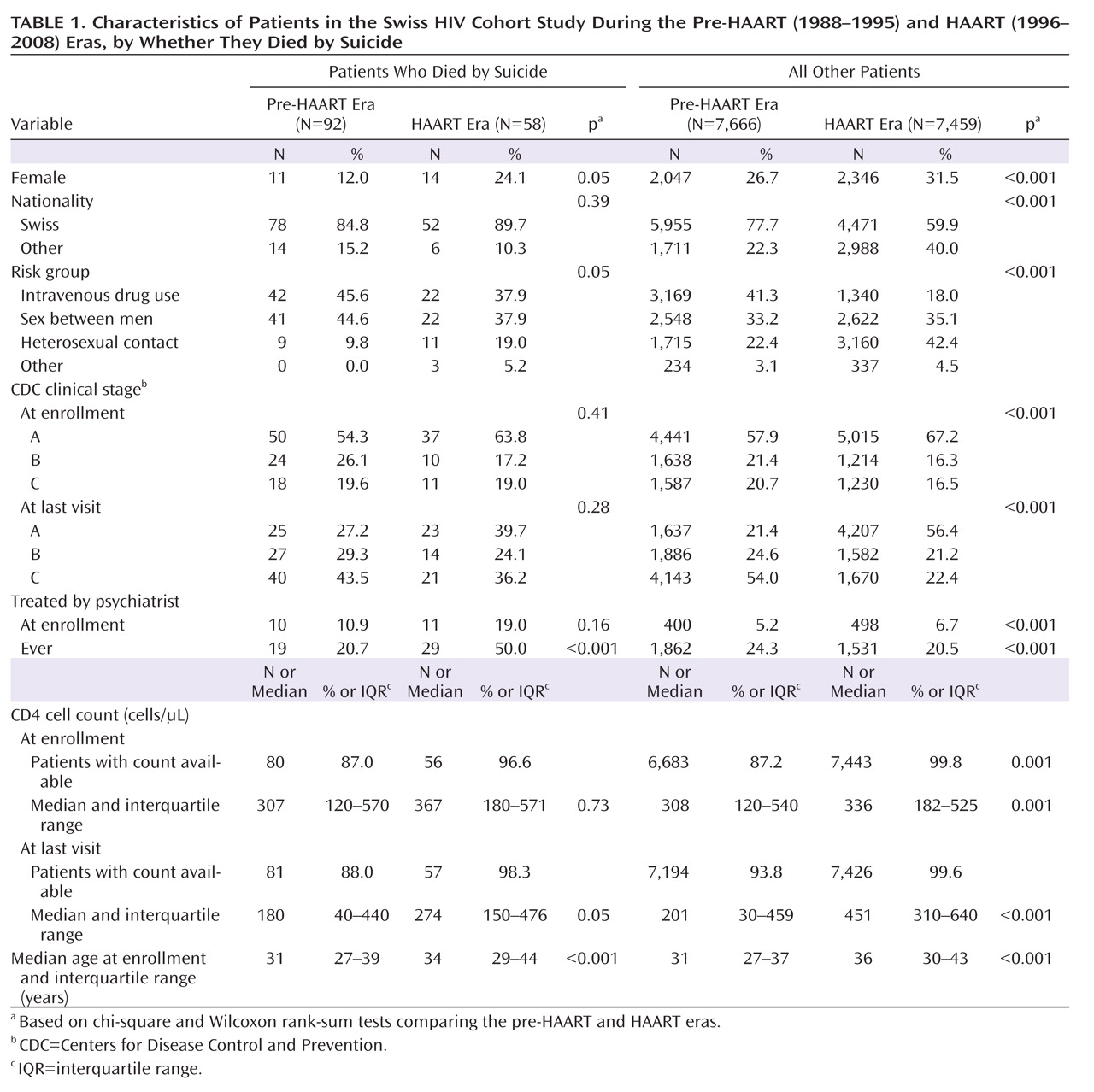

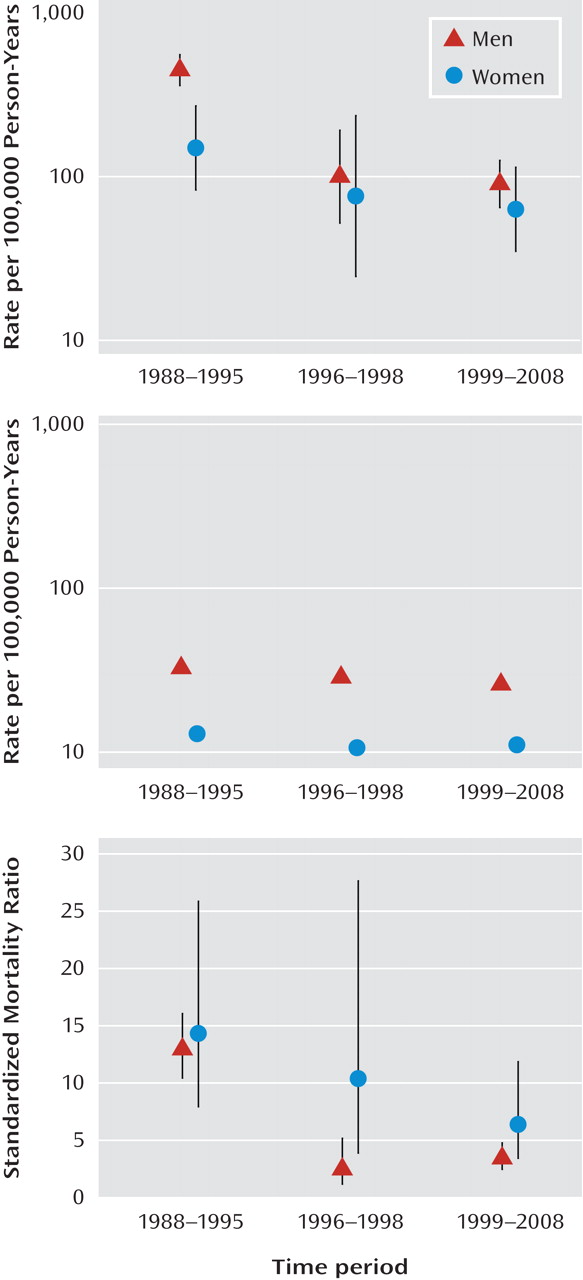

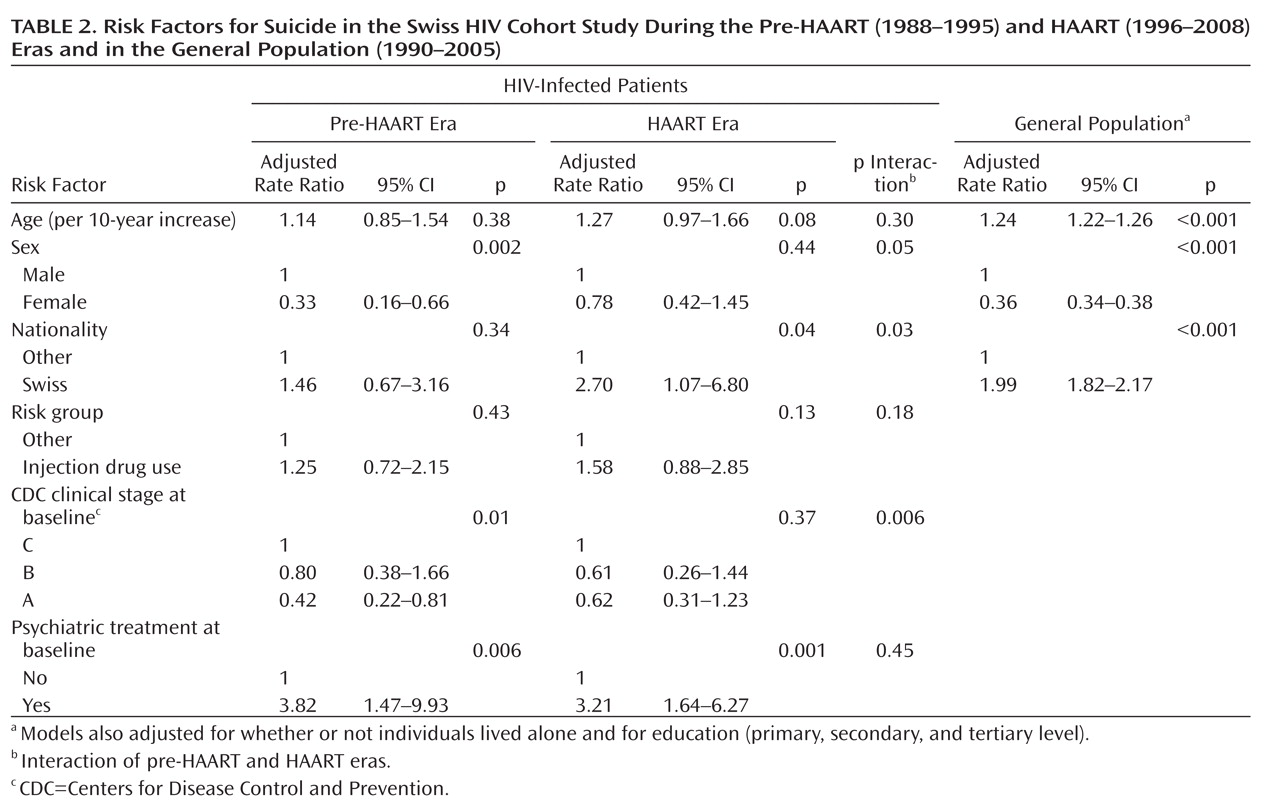

Suicide is an important public health problem in Switzerland: about 1,400 suicides are recorded annually, and Swiss suicide rates are in the top third in Europe and in the top quintile worldwide (

21). We found that in HIV-infected patients, suicide rates declined substantially after the introduction of HAART, in both men and women, with a somewhat steeper decline in men. The association of increasing suicide rates with declining CD4 cell counts supports the hypothesis that HAART-related improvements in disease status may be responsible for the reduction in suicide rates over time. Comparisons with the general population showed that despite this decline, suicide rates remained well above those observed in the general population; the standardized mortality ratio in recent years was 3.5 in HIV-infected men and 5.7 in HIV-infected women. The risk factors observed in the general population—older age, male sex, and Swiss nationality—were also evident in the HIV-infected patients, in whom advanced clinical disease and a history of injection drug use or psychiatric treatment were additional risk factors.

This analysis included more than 15,000 HIV-infected patients who were followed up during the years 1988–2008, and thus it covered the periods both before and after the introduction of HAART. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study was one of the first HIV cohort studies worldwide (

16) and includes about 40% of all patients with HIV and about 70% of patients with AIDS in the country (

22). Our results are therefore likely to be representative for Switzerland and may also apply to other high-income settings. A strength of our study was the inclusion of data from the Swiss National Cohort (

17), which allowed us to compare time trends in suicide rates and risk factors between HIV-infected patients and the general population.

Our study also had several limitations. The suicide rate used to calculate the expected number of suicides was based on all suicides recorded in the general population, which will include suicides in HIV-infected patients. However, the number of suicides in HIV-infected patients is small compared to the total number of suicides, and the bias introduced by their inclusion is negligible. Some variables that were associated with suicide in the general population (for example, marital status) were not collected consistently in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and therefore could not be considered. Sexual orientation is another potential risk factor for suicide. However, because of the limited number of suicides in the HAART era, we were unable to examine its influence in this study. Also, our analysis did not consider differences between the HIV-infected population and the general population other than gender and age. Lifestyle risk factors differ between HIV-infected and noninfected populations. For example, a collaborative analysis of HIV cohort studies found that over 50% of HIV-infected patients were smokers (

23). Smoking is associated with higher rates of suicide; however, this is unlikely to reflect a causal association (

24).

Injection of intravenous drugs is relevant in this context since it is often difficult to distinguish between accidental fatal overdoses and suicides (

25). It would therefore have been preferable to calculate standardized mortality ratios by comparing rates of suicide and overdose between injection drug users who were and were not infected by HIV, but the latter rates are not available in Switzerland. Differences in the coding of deaths could also have introduced bias: a death in an HIV-infected patient may have been more likely to be coded as a suicide, particularly in a patient infected through injection drug use, than a death in the general population. We examined the effect of these potential biases in a sensitivity analysis that excluded injection drug users from the group of HIV-infected patients and included deaths of undetermined intent in the general population. We found that suicide rates remained substantially higher in HIV-infected patients than in the general population.

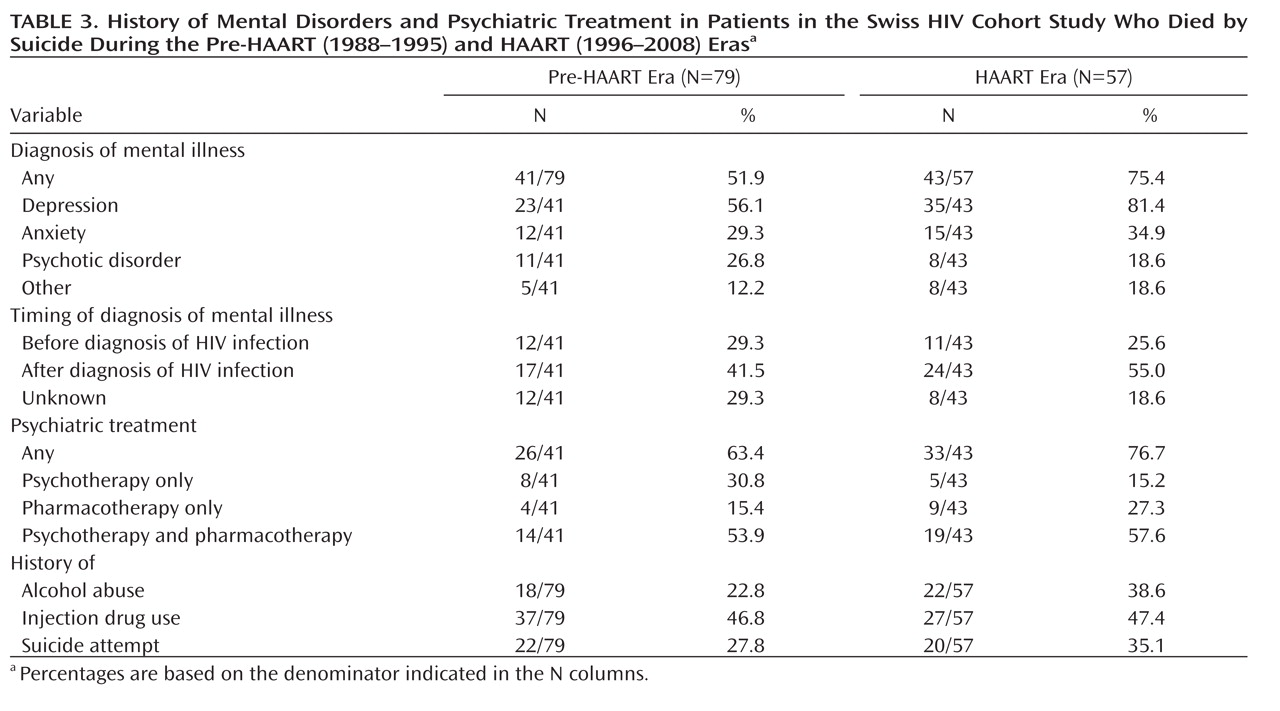

Despite the substantially improved prognosis with HAART, the life expectancy of HIV-positive patients remains lower than in the general population (

11). Furthermore, quality of life is impaired even in patients treated with HAART (

26), and many patients suffer from the stigma and social exclusion associated with HIV infection (

27,

28). The prevalence of depression is high in HIV-infected patients (

29,

30). A diagnosis of mental illness in those who died by suicide was more common in the HAART era than in the pre-HAART era, and patients were more likely to be treated for mental illness in the HAART era. Our study thus indicates that in the pre-HAART era, high suicide rates were driven by disease progression, which at that time could not be prevented, whereas in the HAART era, mental illness has become relatively more important. However, although the number of patients receiving psychiatric care increased, even in the HAART era a substantial proportion of patients remained untreated. These results provide a compelling rationale to improve psychiatric care, including mental health screening and greater access to pharmacological and psychological treatment. Finally, we stress that the survey of mental illness in patients who died by suicide also had limitations: questionnaires were completed by infectious disease specialists, rather than by the treating psychiatrists, and depended on a review of charts. Also, there was no comparison group of patients who did not die by suicide.

With the exception of rural China, suicide rates are higher in men than in women worldwide (

31). In the 1995–2000 period, the suicide rate globally was 26.7 per 100,000 for men and 9.3 per 100,000 for women, for a gender ratio of 2.9 (

32). Among the HIV-infected patients included in this study, the adjusted gender ratio was 2.8 in the pre-HAART era but declined to 1.3 in the HAART era, reflecting the fact that the introduction of HAART was associated with a more substantial reduction in suicide rates in men than in women. Risk factors for suicide are known to differ between genders. For example, a population-based study in Denmark found that unemployment, retirement, being single, and sickness absence were risk factors in men, and having a young child was protective in women (

33). A history of hospitalization for mental illness was a strong risk factor for suicide in both men and women.

Suicide rates also declined in the general population, but this decline was much smaller than the one observed in HIV-infected patients, and it was less pronounced than in other countries during the same period. In Germany, for example, suicide rates in the general population decreased from 24 per 100,000 in 1982 to 14 per 100,000 in 2000 (

34). Of note, active euthanasia is a criminal offense in Switzerland, but assisting someone in dying by suicide is legal if the motive is not selfish (

35). The article of the Swiss penal code (article 115) is from 1918 and was never intended to regulate assisted suicide, but it is used by right-to-die societies to legally offer such assistance to their members (

36). The final step must be taken by the member, by ingesting the lethal dose of barbiturates or starting the injection infusion (

36). A review of 748 suicides assisted by one right-to-die society (including 55 suicides of patients with HIV/AIDS) showed that the number of cases increased from 1990 to 2000 (

36). Furthermore, in contrast to Germany and other countries, Switzerland has no national suicide prevention program (

32).

How do standardized mortality ratios for suicide in HIV-infected patients compare to those in patients with other chronic conditions? In a large Swedish study of cancer patients, the ratio was 1.9 for men and 1.6 for women (

1). Similarly, in an international study including over 725,000 women, the standardized mortality ratio for breast cancer was 1.4 (

37). A ratio of a similar magnitude, 2.3, was found in Swedish patients with multiple sclerosis (

38). Other diseases and conditions that have been shown to be associated with a higher risk of suicide include end-stage renal disease (ratio of 1.84, 95% CI=1.5–2.3) (

39), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ratio of 5.8, 95% CI=3.6–8.8) (

40), and spinal cord injury (ratio in men, 4.7, 95% CI=1.9–9.7, and in women, 19.2, 95% CI=1.8–70.5) (

41). The standardized mortality ratios for suicide observed in our study indicate a higher risk of suicide in HIV-infected patients than in patients with other life-threatening conditions, even in the HAART era.