Risk studies of pediatric bipolar disorder have shown that offspring ages 6 to 18 years of parents with bipolar disorder have an elevated risk of developing early-onset bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders (

3,

5–

11). The largest of these studies is the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) (

5). The BIOS showed that school-age offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had significantly higher rates of any axis I disorder, bipolar spectrum disorders (mostly not otherwise specified), major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than offspring of community comparison parents. However, after adjustment for both biological parents' non-bipolar psychopathology, the differences in the rates of major depressive disorder, disruptive behavior disorders, and ADHD were no longer significant.

The above-noted studies were conducted with offspring age 6 and older. However, parents with either a personal or a family history of bipolar disorder often wonder whether their preschool child's behavioral and emotional problems are due to a bipolar diathesis, since some of these problems are reminiscent of their own or their relatives' problems during childhood. The few studies of preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder suggest that relative to offspring of comparison parents (mostly healthy), these children have higher rates of observed behavioral disinhibition, disruptive and depressive symptoms, fidgetiness, hyperactivity, disproportionate levels of aggression, and difficulty managing anger and hostile impulses during observed interactions with peers and unknown adults (

12–

16). Some of these problems (disruptive and depressive symptoms) were found to persist and even increase (e.g., depression) over time (

14). However, further research is needed to confirm these findings since these studies used very small samples of children and parents with bipolar disorder and had other methodological limitations, as delineated elsewhere (

5,

7).

Epidemiological and clinical studies have shown that clinically relevant symptoms and psychiatric disorders are reliably diagnosed in preschool children as young as 2 years old (

17–

20). Symptoms of major depressive disorder are also reliably ascertained in this population and are associated with significant psychosocial impairment and high rates of mood disorders in family members (

18,

19,

21,

22). Although several case reports (

23–

27) and a recent study (

24) showed that preschoolers can be diagnosed with DSM-IV bipolar disorder, the diagnosis of mania in young children remains controversial, and further longitudinal research is warranted.

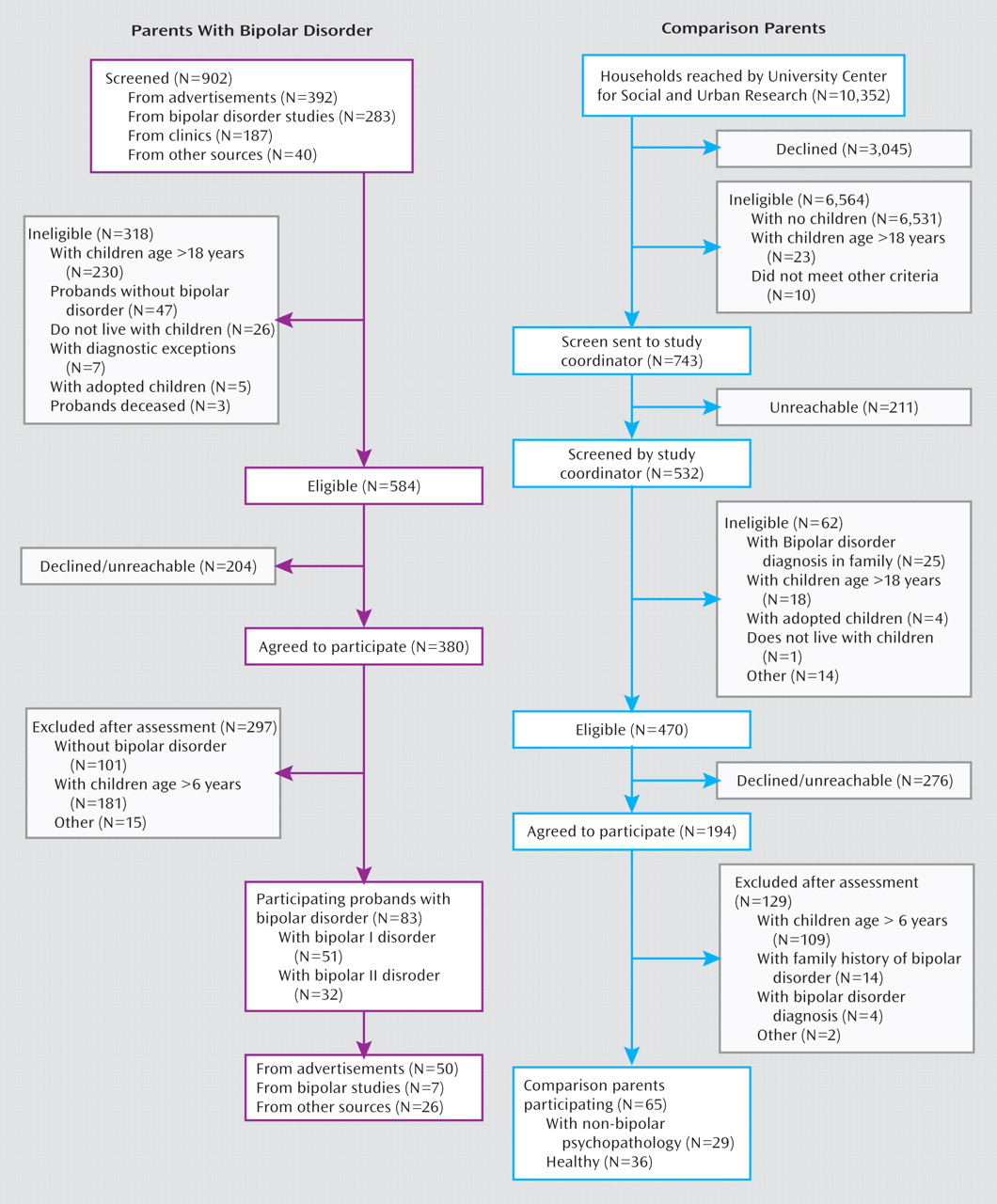

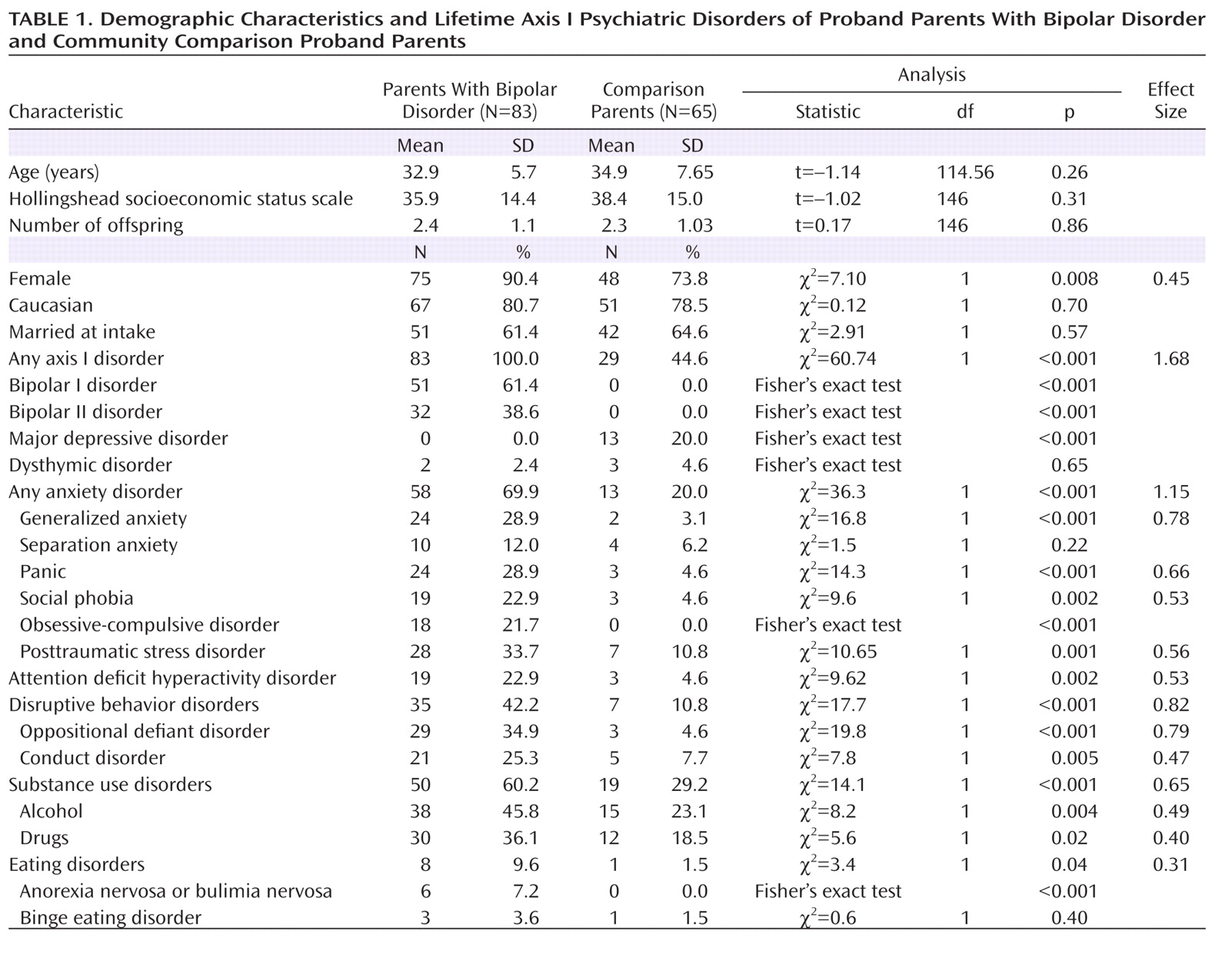

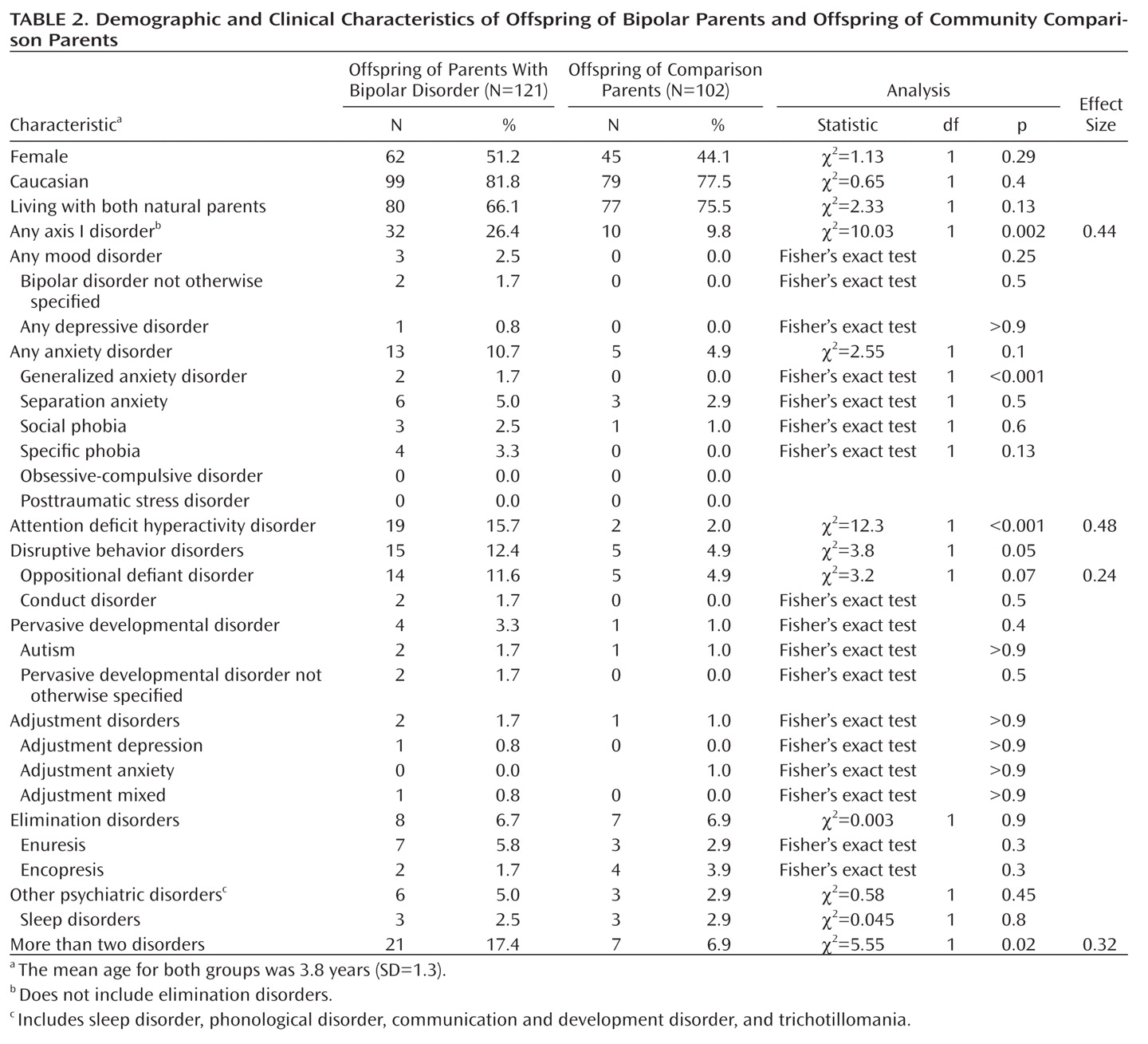

Our primary goal in this study was to evaluate whether preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had significantly more lifetime DSM-IV axis I disorders than a demographically matched sample of preschool offspring of community parents (with and without non-bipolar psychopathology). In addition to categorical diagnoses, since subthreshold mood symptoms may precede the onset of full-blown mood disorders, the presence and severity of mood symptoms at intake were explored. Based on the available literature, we hypothesized that offspring of parents with bipolar disorder would have higher rates of ADHD, disruptive behavior disorders, and anxiety and mood disorders and higher ratings on depressive and manic symptom scales relative to offspring of comparison parents.

Discussion

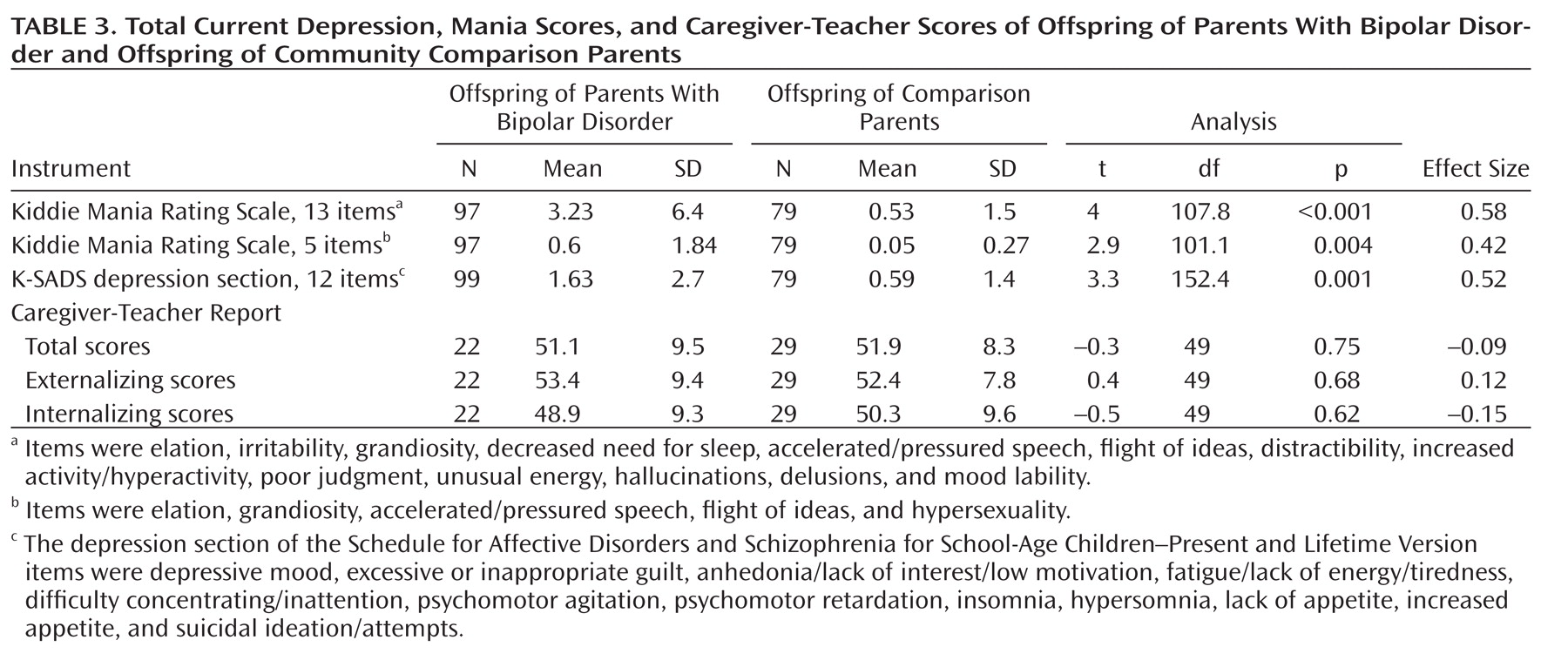

Relative to preschool offspring of comparison parents and after adjustment for both biological parents' non-bipolar disorders and within-family correlations, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had an eightfold greater rate of ADHD and significantly higher rates of having two or more psychiatric disorders. There were no differences in the rates of psychiatric disorders between offspring of parents with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. While only three offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had mood disorders, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, especially offspring with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, had significantly more severe current manic and depressive symptoms than offspring of comparison parents. In a subset of children, caregivers or teachers reported significantly more psychopathology in children with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder than in those without these disorders.

Before we discuss these findings, the limitations of this study deserve comment. First, as in any pediatric study, and especially with preschoolers, the main informants for both the bipolar and comparison parent groups were the mothers. Moreover, in about half of the cases, the psychopathology in the biological co-parents was ascertained by interviewing the main informant. However, there were no differences between the bipolar and comparison parent groups in the rate of mothers serving as main informants and in the proportion of direct and indirect interviews of biological co-parents. Second, the children's psychopathology was ascertained through parents, and parental psychiatric illnesses could have inflated the rates of reported psychopathology in offspring. However, although the literature regarding this issue is controversial, it appears that if there is any effect, it is small (

42–

44). Similar biases existed for both parent groups because about 50% of the comparison parents had axis I disorders, and rates of psychiatric disorders in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder were not associated with their mothers' lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder and acute mood symptoms at intake. In contrast to the above arguments, there were no differences in caregiver scores between offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and offspring of comparison parents. Nevertheless, only a few offspring who had caregiver reports had ADHD and/or oppositional defiant disorder, and the rest of the sample was healthy. To help clarify these issues, more confirmatory work is needed using parent reports in tandem with measures less likely to be influenced by bias (direct observation measurements in particular). Third, the nature of the study could have attracted parents with more severe disorders. Nevertheless, the rates of psychiatric disorders in the parents with bipolar disorder were similar to those reported in the adult bipolar literature (

45,

46). Also, even though BIOS is not an epidemiological study, the lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders observed in the comparison parent group was similar to that reported in a recent large epidemiological study in the United States (

47). Fourth, no direct observations of the preschoolers were available. Finally, although behavioral and mood disorders are identifiable in preschoolers, more research is needed on the way these disorders, particularly mania, manifest in preschoolers and on what would be the most appropriate methods and instruments to assess these conditions in this population.

Both biological parents of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had higher rates of psychopathology than comparison parents, and thus it is not surprising that their offspring also had significantly more psychopathology. In fact, after taking into account both biological parents' psychopathology, between-group differences in having any axis I disorder and disruptive behavior disorders were no longer significant. However, rates of ADHD remained significantly higher in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Studies of preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder that evaluated dimensional symptoms rather than categorical disorders have also shown that these children have symptoms frequently observed in children with ADHD, such as behavioral disinhibition, hyperactivity, and difficulty managing anger and hostile impulses (

15,

17,

19).

It is not yet clear why the results of the BIOS preschool-age study contrast with those of the BIOS and other school-age high-risk studies (i.e., high prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders) (

14,

48–

50). It is possible that the K-SADS-PL was not sensitive enough to detect mood and anxiety disorders in preschoolers. However, rates of disorders ascertained through the K-SADS-PL are similar to those found in epidemiological studies (

19,

35), and one epidemiological study using an unmodified K-SADS-PL (

51) diagnosed mood and anxiety disorders in preschoolers at rates similar to the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (

19). It is also probable that in comparison with older children, nonspecific symptoms such as irritability, hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity are ubiquitous manifestations of externalizing as well as internalizing psychopathology in preschool children (

9,

14,

52–

55). In contrast, because of the emotional and cognitive developmental level in this population, more specific manic symptoms, such as grandiosity and elation, or depressive symptoms, such as hopelessness and severe melancholia, may not yet be evident, and if they are present, they are more difficult to ascertain (

24). Thus, in BIOS, although these nonspecific externalizing symptoms may indeed be accounted for by early-childhood ADHD, it is also possible that they are prodromal or subthreshold symptoms of mood disorders, especially when accompanied by mood symptoms and a family history of mood disorders (

8,

9,

14,

16,

53,

56–

59). In fact, in BIOS, preschool children in the bipolar parent group with externalizing disorders had significantly more manic and depressive symptoms than offspring in the bipolar parent group without these disorders and offspring in the comparison parent group. As reported in the literature, these children are at high risk for developing mood disorders (

60–

64).

Only three offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had subthreshold mood disorders. However, these children have not reached the age of highest risk for developing bipolar and major depressive disorders, and it has been consistently shown that the rate of these disorders is likely to increase with age (

5,

8,

9,

65,

66). Despite the above findings, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, and especially offspring with externalizing disorders, had significantly more severe manic (including elation) and depressive symptoms than offspring of comparison parents. However, it is important to note that, in general, the severity of individual manic symptoms was subclinical. Furthermore, additional research is needed to define the boundaries between bipolar symptoms (e.g., elation, grandiosity, irritability, and mood episodicity) and the expected broad mood fluctuations and normal fantasies about special powers and abilities and appropriately increased self-concept commonly observed in preschool children (

24,

67).

Because BIOS is prospectively following all children, we will be able to address these developmental issues and delineate the types and severity of symptoms that predict subsequent conversion to bipolar disorder. Also, because approximately 70% of the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder in our sample did not have any diagnosable psychiatric illness and very few had subthreshold mood disorders, there is a window of opportunity for primary prevention in this high-risk population. Thus, psychosocial interventions aimed at helping preschool children regulate their mood, which have been found to be efficacious in preschoolers with disruptive behavior disorders and in older children with subthreshold mood disorders, and effective treatment of parental psychopathology may diminish the severity of, and perhaps delay or prevent the new onset of, psychopathology in preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder (

4,

24,

68–

71).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carol Kostek and Mary Kay Gill, M.S.N., for their assistance with manuscript preparation, the University Center for Social and Urban Research staff, the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study interviewers (Ryan Brown, Nick Curcio, Ronna Currie, Gail Oterson, Elizabeth Picard, and Lindsay Virgin), Scott Turkin, M.D., and the Dubois Regional Medical Center Behavioral Health Services staff for their collaboration. The authors also thank Drs. Shelli Avenevoli and Editha Nottelmann from NIMH for their support.