Others have argued that a body of empirical evidence for psychodynamic treatments exists and is underappreciated in the context of contemporary emphasis on short-term, manualized, and symptom-focused treatments and targeted medications (

3–5). Over the past several years, metaanalyses have appeared in mainstream research outlets that argue for the efficacy of psychodynamic treatments for specific disorders (

6–11). Gabbard et al. (

12) describe a “hierarchy of evidence” ranging from case-studies and uncontrolled trials to randomized controlled trials that support the utility, if not the efficacy, of various forms of psychodynamic psychotherapy for treatment of patients with a wide range of DSM-IV axis I and II psychiatric disorders. Although each of these metaanalyses attempts, in its own way, to make use only of studies that are considered of high enough quality to warrant inclusion in a metaanalysis, there is sharp disagreement in the field about whether the quality and number of studies included is sufficient to warrant the conclusions drawn.

Ambiguity about the state of psychodynamic empirical research presents a significant problem for training and practice in the mental health fields. The objective evaluation of the quality of randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic psychotherapy is a cogent place to begin the process of correcting this problem. Such trials are widely accepted in medicine as the gold standard for assessing treatment efficacy, and there is good conceptual agreement about what constitutes a well-conducted trial (

13). The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Statement, which has been adopted by most major medical journals, identifies 22 elements that are important in reporting randomized controlled trials (

14). However, the CONSORT checklist and other similar measures, designed primarily to assess studies of pharmacological or medical interventions, fail to adequately assess the psychotherapy literature for several reasons. First, they do not include items that are specific and essential to psychotherapy trials, such as the length of follow-up or the extent of training or supervision of psychotherapy. Second, they focus on the quality of description in the written article, with less explicit focus on what was

done in the actual trial, thus deemphasizing such essential details as assessment of adherence to the treatment actually delivered. Third, they pay insufficient attention to the quality and credibility of comparison treatments, as this is less of an issue for studies using pill placebo for the comparison group. And fourth, psychometric evaluation of CONSORT items has never been reported, nor have the items been used to quantify overall quality scores. An extension of the CONSORT Statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacological treatment (including, for example, surgery, technical interventions, devices, rehabilitation, psychotherapy, and behavioral intervention) published in 2008 consists of further elaboration of 11 of the checklist items, addition of one item, and modification of the flow diagram (

15). Although helpful, this extension remains nonspecific to psychotherapy, focuses on description over conduct of the trials, and lacks psychometric evaluation.

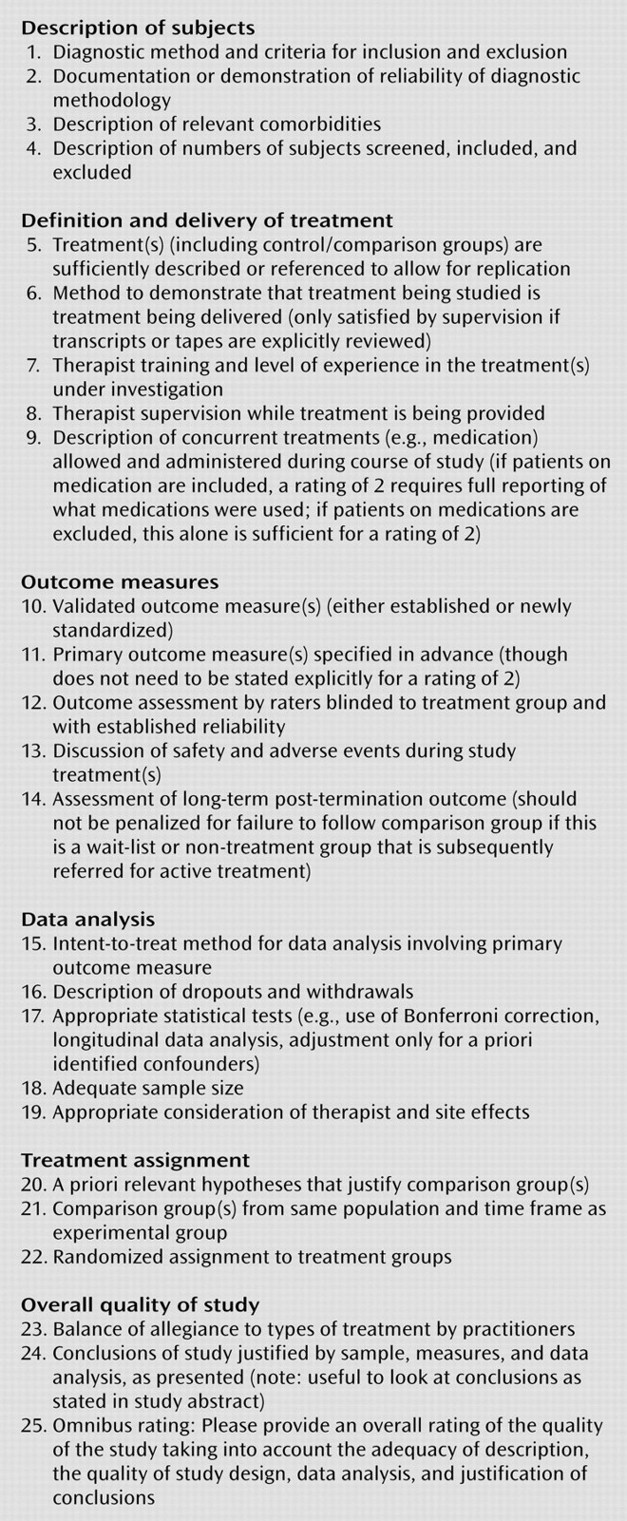

As part of an effort to clarify the state of psychodynamic psychotherapy research, the Ad Hoc Subcommittee for Evaluation of the Evidence Base for Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (appointed in 2004 by the APA Committee on Research on Psychiatric Treatments) developed the Randomized Controlled Trial of Psychotherapy Quality Rating Scale (RCT-PQRS). This 25-item questionnaire was designed by experienced psychiatric and psychotherapy researchers from a variety of theoretical backgrounds as a systematic way to rate the quality of randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy. The scale is designed to be used by individuals with considerable experience in reading and executing psychotherapy trials but requires only 10 to 15 minutes to rate, in addition to the time spent reading the paper to which it is applied. The scale yields a 24-item total score that has good psychometric properties and captures the overall quality of design, implementation, and reporting of psychotherapy trials. (Item 25 is an omnibus item, more about which below.)

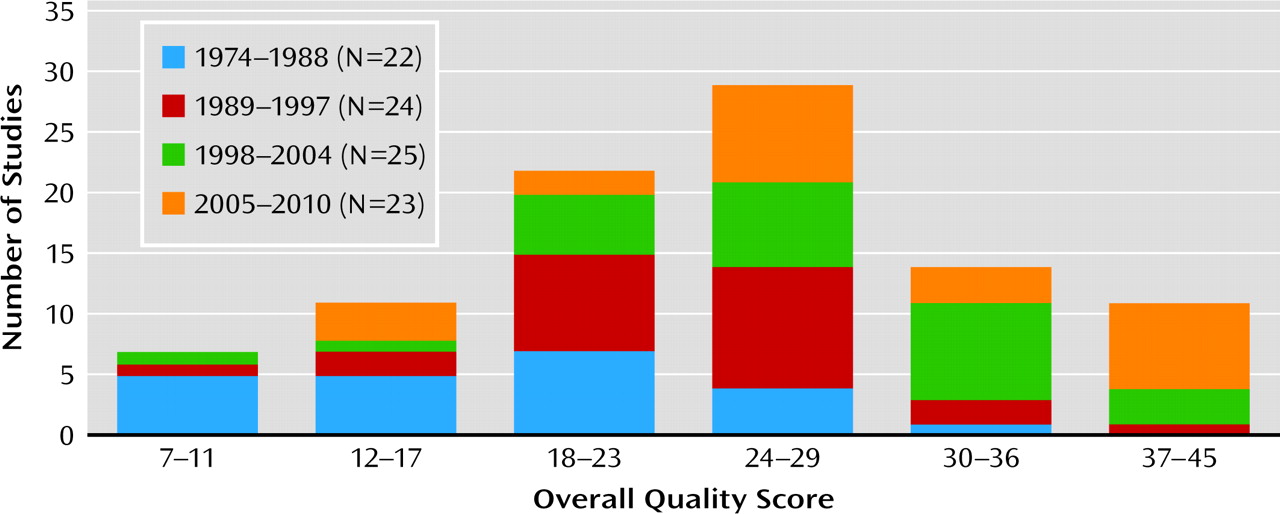

In this article, we report psychometric properties of the RCT-PQRS based on application of the scale to all 94 randomized controlled trials of individual and group psychodynamic psychotherapy published between 1974 and May 2010 that we were able to locate. We then describe the results of applying this measure to the psychodynamic outcome literature. Our hypotheses were 1) that the overall quality of randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic psychotherapy has improved over time, from a largely inadequate implementation in the 1970s and 1980s to more rigorous implementation in the 1990s and 2000s; 2) that some aspects of psychodynamic psychotherapy trials, including characterization of patients, reliable and valid measurement of outcome, and manualization of treatment, are now being done quite well; and 3) that some aspects of psychodynamic psychotherapy trials, including reporting of therapist training and supervision, measurement of treatment adherence, analysis of therapist or study site effects, and reporting of concurrent treatments and adverse events during treatment, remain lacking.

Discussion

In this evaluation, we examined a large amount of study-derived data collected to describe the utility of psychodynamic psychotherapy for psychiatric illness. On this basis, it appears that there is both good and bad news about the quality of randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic psychotherapy. The good news is that there are at least 94 randomized controlled trials published to date addressing the efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy, spanning a range of diagnoses, and more than half of these (57%) are of adequate quality. The 94 studies represent 103 comparisons between the outcome of psychodynamic psychotherapy and a nondynamic comparator at termination. In the 63 comparisons of dynamic treatment and an active comparator, dynamic treatment was found to be superior in almost 10% and inferior in 16%, and the analyses failed to find a difference in almost 75%. In the 40 comparisons of dynamic treatment and an inactive comparator, dynamic treatment was superior in 68%, there was no evidence for difference in 30%, and dynamic treatment was inferior in one study. We obtained similar results if only studies of good quality are included. In comparisons of good quality studies involving dynamic treatment against an active comparator, dynamic treatment was superior in 15% and inferior in 13%, and evidence was lacking in either direction in 72%. In comparisons against an inactive treatment, dynamic treatment was superior in 75% and lacked evidence in either direction in 25%.

However, it is clear that there are significant quality problems in a significant percentage of randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic psychotherapy, and this may be true for trials of other psychotherapies as well. Based on the 94 studies reviewed here, reporting of safety and adverse events, intent-to-treat method in data analysis, and consideration of therapist and study site effects are lacking. Furthermore, 57% of all comparison and 54% of comparisons from studies of adequate quality failed to find any statistical differences between outcome from psychodynamic treatment and a comparator. As Milrod (

35) has pointed out, if a randomized controlled trial is not powered for equivalence (that is, lacks sufficient enough power to detect differences between groups such that the absence of a significant difference can be interpreted as equivalence in efficacy or effectiveness of the treatments), it is impossible to conclude from the absence of a finding that dynamic treatment is as good as or not worse than the comparator treatment. In fact, if we use the rough approximation that a total sample size of at least 250 is required in order to be powered for equivalence (the actual number depends on the measures used), one of the comparisons reviewed here that failed to show a difference between psychodynamic treatment and an active comparator met that criterion (

36).

When considered from this perspective, an important finding is that of 63 statistical comparisons based on randomized controlled trials of adequate quality, six showed psychodynamic psychotherapy to be superior to an active comparator, 18 showed it to be superior to an inactive comparator, and one showed it to be equivalent to an active comparator. The empirical support for psychodynamic psychotherapy comes down to these 25 comparisons (in boldface in online data supplement). Most of the rest of even the trials of adequate quality are uninformative (33 studies), and several suggest that psychodynamic psychotherapy is worse than an active or inactive comparator (five studies).

Therefore, it is our conclusion that although the overall results are promising, further high-quality and adequately powered randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic psychotherapy are urgently needed. The standards by which a treatment is considered “evidence-based” for the purposes of inclusion in practice standards, educational curricula, or health care reimbursement vary widely. Perhaps the most commonly cited standard, first published by Chambless and Hollon in 1996 from an American Psychological Association Division 12 (clinical psychology) task force (

37), requires at least two well-conducted trials using manuals, showing superiority or equivalence for a specific disorder, and performed by separate research groups, for a treatment to be considered “well-established.” By this standard, the 25 high-quality trials reviewed could have been more than enough for psychodynamic psychotherapy to be considered “empirically validated.” However, these 25 trials covered a wide range of diagnoses and used different manuals or forms of dynamic therapy. In addition, the significant number of trials that failed to find differences between dynamic and active or inactive comparators, most of which were not powered for equivalence, as well as a handful of trials that found dynamic therapies to be inferior to active comparators, suggest that more work is needed. It remains necessary to identify specific dynamic treatments that are empirically validated for specific disorders.

One finding of this review is that the clearest predictor of outcome from randomized trials of psychodynamic psychotherapy is whether or not the treatment was tested against an active or an inactive comparison treatment. We suspect that this finding is common to randomized controlled trials of all psychotherapies. There is no apparent relationship in this group of studies between study quality and the outcome measured in that study.

We have taken a highly critical view of data collected in support of psychodynamic psychotherapy in this evaluation. Few domains of psychiatric intervention have yet been evaluated so critically, and we emphasize that many domains of psychotherapy outcome research (i.e., CBT, cognitive-behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and supportive psychotherapy, to name some) may not fare significantly better, despite the far greater number of outcome studies within these other domains to evaluate. We are currently embarking on a similar review of studies of CBT for depression. We believe that this is an appropriate stance, and we anticipate that this assessment can help move psychotherapy research in a direction toward better-designed outcome studies in the future. Thus far, proponents of other studied forms of specific psychotherapy, most notably CBT, have yet to dissect the quality of studies that support its efficacy.

For three items in the RCT-PQRS, at least half of the studies were scored as “poor”: item 13 (reporting of safety and adverse events), item 15 (intent-to-treat method reported in data analysis), and item 19 (consideration of therapist and study site effects). Individual item scores must be regarded with caution because we have not yet established a high degree of interrater reliability on individual items. However, we believe that all three of these items represent significant deficits in the psychodynamic psychotherapy research literature that are still being insufficiently addressed (1). It is well known by clinicians that all efficacious treatments, whether they be psychotherapy or psychopharmacology, carry with them some risk of adverse effects, yet the randomized controlled trial literature in psychotherapy in general does not systematically report and discuss adverse events as do, for example, most good studies of medication (2). While there has been significant improvement in the area of intent-to-treat analysis, many randomized controlled trials of psychodynamic psychotherapy still focus primarily on “completer” analyses and do not adequately employ the intent-to-treat method, which is a standard of the evidence-based medicine literature. Although intent-to-treat analyses also have certain limitations, they are the best starting point for addressing patient dropout in considering which treatments work best (

38–40). Finally, a large literature supports the importance of individual therapist and study site effects in psychotherapy outcome (

41–43), but the psychotherapy randomized controlled trial literature has not yet adequately responded by incorporating such considerations into a discussion of results, and even less into study design.

The RCT-PQRS focuses only on the reporting, execution, and justification of design decisions made in a given report of a randomized controlled trial, but not on how these decisions affect the broader question of when results can be applied to real-world clinical practice. In other words, the measure addresses the importance of accurately and reliably quantifying the internal validity of a randomized controlled trial, while tracking generalizability less (

3). As one example of this, the diagnostic categories described in Table 2 are just one conventional way of parsing the patient samples and are by no means the only way to subdivide these studies. None of the analyses in this article relied on diagnostic categories. How-ever, future quality-based reviews and meta-analyses will need to address this issue.

The development and application of our quality measure have several significant limitations. First, the accuracy of our ratings is necessarily limited by the extent of the information provided by the authors in their study descriptions. In some cases, the extent to which the authors describe a comparison treatment such as “treatment as usual” as active or inactive could have important consequences in rating the study. However, in our rating of active versus inactive comparator treatments, we observed no significant differences between raters and therefore do not believe that there was much ambiguity in these ratings for the articles reviewed. Second, we have not yet developed and published a manual for the RCT-PQRS that would allow for greater single-item reliability across raters. Lack of reliability limits our ability to interpret individual item scores. Although a manual would likely improve item reliability, it would increase the time it takes to learn and apply the measure and might not affect the overall scores. Third, we have not yet collected sufficient data from the RCT-PQRS to study other ways of aggregating or weighting individual items. We anticipate performing the appropriate analyses as we collect data on a larger number and broader range of randomized controlled trials of psychotherapies. Finally, given that raters of the studies are not blind to study outcome or, in most cases, the allegiance of the study authors, the quality scale is theoretically susceptible to bias. Blinding the studies by removing the names of treatments or the direction of findings would be difficult if not impossible, and the blinding process itself would be subject to biases. We addressed the potential for bias by making sure that our raters (and the designers of the scale) were drawn from a range of areas of clinical and research expertise, including pharmacotherapy, CBT, and psychodynamic psychotherapies. We observed no significant relationship between quality ratings and theoretical orientation of raters. In fact, the mean total quality score was slightly lower for raters with a psychodynamic orientation than for those without.

We hope that this better-operationalized evaluation of the quality of psychotherapy outcome studies will help guide investigators across all areas of psychotherapy research toward more scientifically credible, better-articulated research.