Clinical and epidemiological research has extensively documented the high prevalence of alcohol and drug use disorders among individuals with schizophrenia (

1–4). These forms of comorbidity have been shown to have severe consequences for clinical course and treatment response (

3,

5–9), worsening the outcome of disorders that are already ranked among the leading causes of years lost due to disability when considered independently (

10). Recent data from population surveys have also confirmed that a great majority of acts of violence committed by persons with schizophrenia are attributable to those with co-occurring substance abuse (

11). Taken together, these findings underscore the public health necessity of reducing substance use among individuals with schizophrenia as well as the important treatment implications of understanding the nature of these associations.

Research on these forms of comorbidity has focused in large part on testing causal models of association whereby the use of certain substances may increase the risk of psychotic symptoms or where substances are consumed as a means of alleviating symptoms or negative emotional states (

1,

2,

12,

13). However, a fundamental barrier to examining either hypothesis concerns the difficulties inherent in characterizing the time-limited effects of psychoactive substances relative to fluctuations in psychotic symptoms as they occur naturally in daily life. Computerized ambulatory monitoring techniques such as ecological momentary assessment or the experience sampling method have recently led to important advances in the study of temporal associations among daily life variables associated with use of alcohol or illicit drugs (

14–18) as well as in persons with schizophrenia (

19–21). These methods employ repeated within-day assessments capable of characterizing the association of behaviors and psychological states over brief time intervals, and the electronic nature of data collection overcomes errors in establishing the timing of frequent reports when using paper-based ambulatory monitoring methods (

22,

23). Depending on the direction of risk, the confirmation of prospective within-day associations between substance use and psychotic symptoms would have important implications for understanding the development of substance use, abuse, or dependence in patients with schizophrenia or aid in understanding the biochemical mechanisms implicated in the expression of this disorder.

In this study, we examined the association of substance use with psychological states and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Participants were followed intensively for 1 week using computerized ambulatory monitoring techniques to provide reports of diverse psychological states and behaviors as they were experienced in real time and across diverse daily life contexts. We compared prospective associations of negative mood, perceived stress, and psychotic symptoms with the subsequent use of alcohol, cannabis, and other illicit substances, as well as prospective associations in the reverse direction. All analyses controlled for the status of the predicted outcome at the time of predictor variable assessment.

Results

The clinical and electronic interview variables for the study are presented in

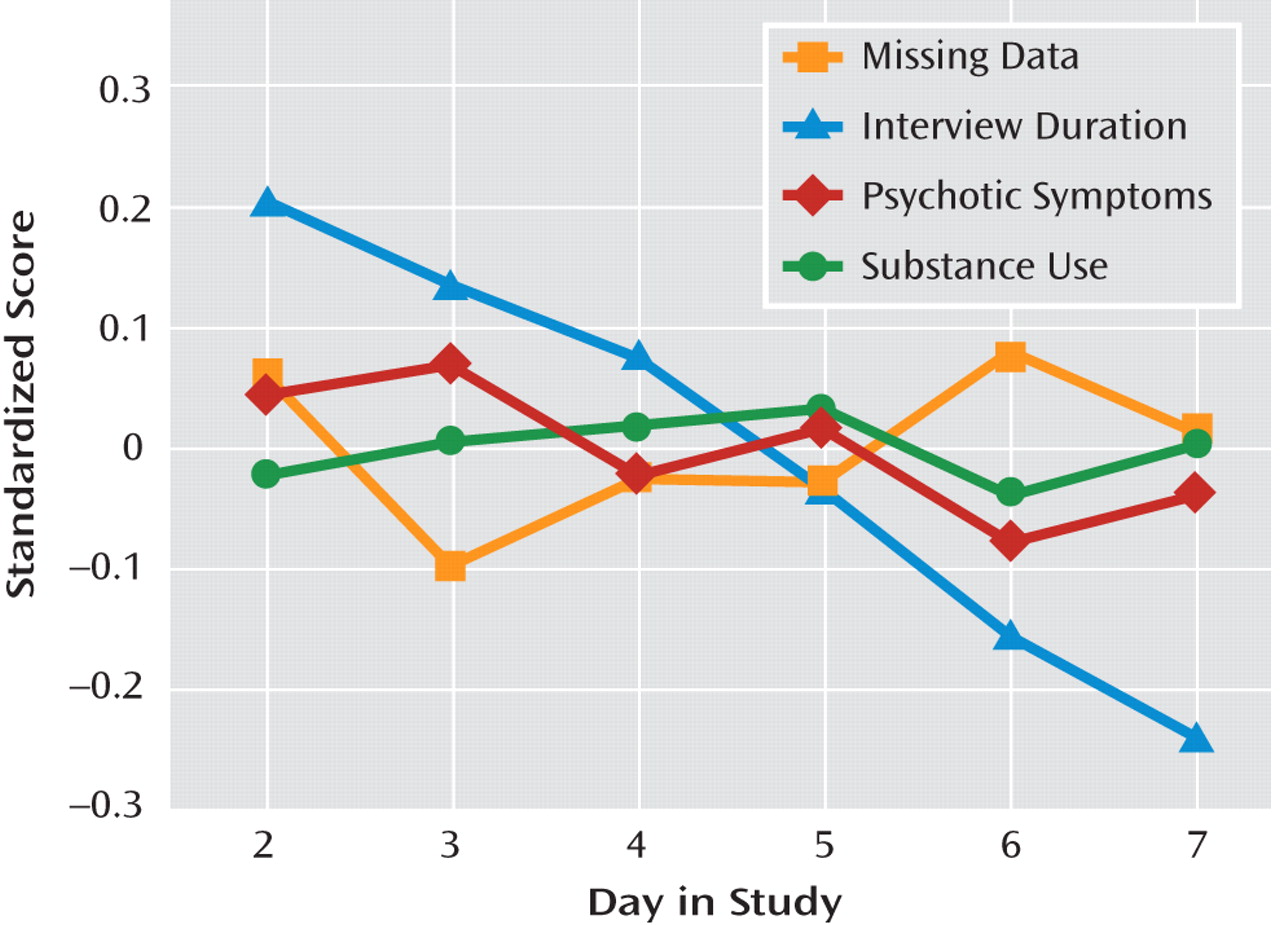

Table 1. On average, participants experienced moderate overall clinical severity (PANSS total score=66.77, SD=17.11), with individual scores ranging from mildly to severely ill (range=34-108). Participants responded to 72.1% (SD=19.1%) of the programmed electronic interviews over the assessment week, generating 2,737 valid observations. Electronic assessment reports of psychotic symptoms during this period were associated with higher levels of concurrent sad mood (γ=0.307, SE=0.071, t=4.306, p<0.001), anxious mood (γ=0.489, SE=0.086, t=5.658, p<0.001), and perceived event negativity (γ=0.453, SE=0.109, t=4.151, p<0.001). Substance use was more frequent among individuals with a lifetime substance use disorder (γ=0.872, SE=0.373, t=2.339, p<0.05) but did not vary by age or sex. Of all positive substance use reports (N=189), 13.8% involved more than one class of substance. The number of assessments per day in which psychotic symptoms, substance use, or missing data were observed was unrelated to day in study (

Figure 1).However, participants required less time to respond to electronic interviews as the study progressed (γ=−17.189, SE=2.133, t=−8.058, p<0.001). Approximately 8% of the sample (N=12) reported no use of prescribed medication over the assessment week. However, 76% of the sample (N=110) reported medication use for the majority of assessment days, and 41% (N=59) reported medication use across all days of the study.

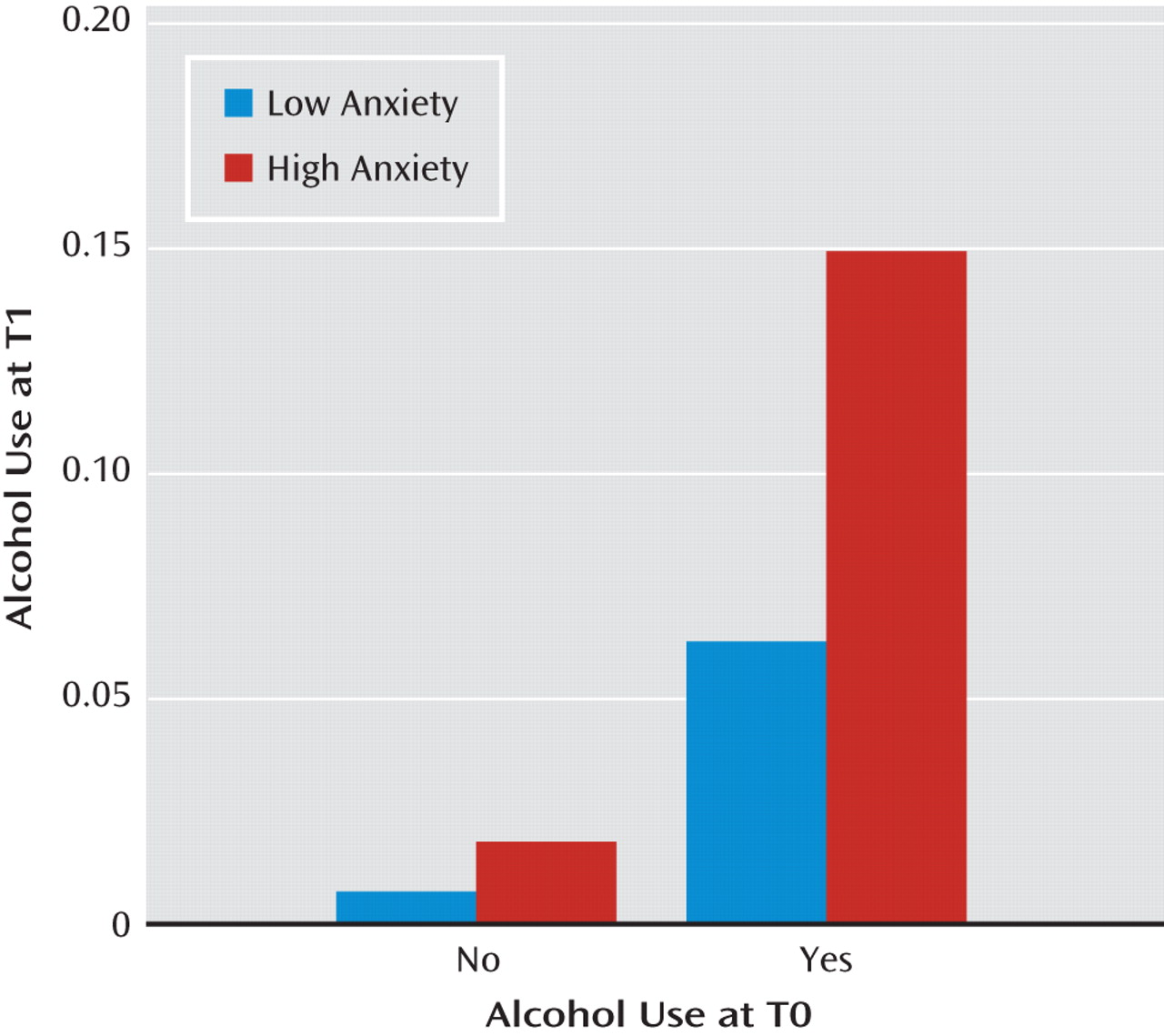

Table 2 presents the associations of negative mood states, event negativity, and psychotic symptoms measured at any given assessment with the onset of substance use at the subsequent assessment of the same day. For the aggregate category of any psychoactive substance, both sad mood (γ=0.311, SE=0.112, t=2.786, p<0.01) and psychotic symptoms (γ=1.374, SE=0.354, t=3.878, p<0.001) were significant risk factors for later substance use. These patterns of significance were similar for the category of other illicit or nonprescribed psychoactive substances. Concerning predictors of alcohol use, psychotic symptoms remained a significant risk factor (γ=1.022, SE=0.343, t=2.983, p<0.01), but prospective effects were also observed for anxious mood (γ=0.206, SE=0.056, t=3.712, p<0.001). This latter association is illustrated in

Figure 2 as a function of baseline (T0) alcohol consumption, suggesting a proportionally greater role for anxiety in the continuation of alcohol use, as opposed to its initial onset. The table also demonstrates that cannabis use was more likely following anxious mood (γ=0.104, SE=0.043, t=2.408, p<0.05) and perceived negative events (γ=0.367, SE=0.045, t=8.165, p<0.001), but it was less likely following sad mood (γ=−0.297, SE=0.047, t=−6.324, p<0.001).

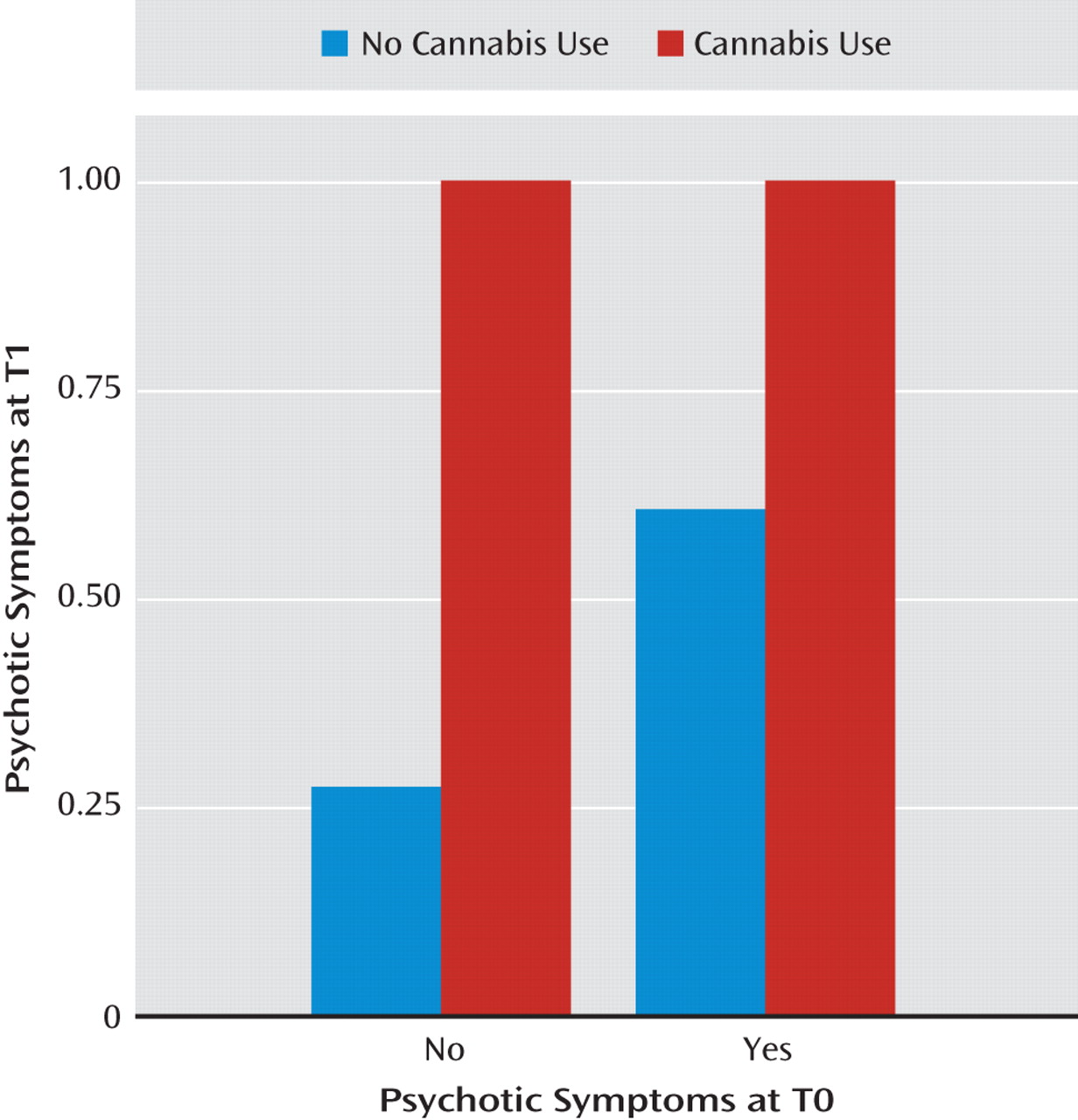

Table 3 presents the reverse prospective associations, where substance use was examined as a predictor of later psychotic symptoms, negative moods, or perceived event negativity. The aggregate analyses demonstrate that the use of any psychoactive substance was generally associated with increases in anxiety (γ=0.583, SE=0.244, t=2.385, p<0.05) as well as with an increased likelihood of psychotic symptom onset (γ=1.092, SE=0.350, t=3.119, p<0.01). Cannabis use was associated with later decreases in perceived event negativity (γ=<0.484, SE=0.218, t=−2.222, p<0.05) but with the strongest increases observed in the risk of psychotic symptoms (γ=3.043, SE=0.455, t=6.683, p<0.001). As demonstrated in

Figure 3, use of cannabis was associated both with initial psychotic symptom onset among individuals who did not report symptoms at baseline and with a greater risk for the continuation of symptoms among those who already reported hallucinations or delusions at baseline. An increase in psychotic symptoms (

Table 3) was also associated with use of other illicit or nonprescribed substances (γ=0.913, SE=0.335, t=2.730, p<0.01), as was an increase in anxious mood (γ=0.549, SE=0.243, t=2.256, p<0.05). No significant prospective effects were observed for alcohol use relative to later psychotic symptoms, mood states, or perceived event negativity.

All models were examined for potential biases associated with prescribed medication use, systematic variation in missing data, time-of-day effects, and polysubstance use. These time-lagged analyses demonstrated that medication use did not influence the direction or significance of any of the observed associations, and the presence of psychotic symptoms or use of psychoactive substances was not associated with the frequency of missing data at the subsequent assessment. In order to examine whether the observed effects may reflect differences in variable frequency at different times of the day rather than true associations among the variables, time was included as a covariate in all models. The effects of specific substances were also examined by excluding all cases of polysubstance use. These secondary analyses demonstrated that time of day and polysubstance use had little effect on the significance of findings, except that anxious mood no longer predicted later cannabis use and the association of any substance use with later psychotic symptoms now fell short of statistical significance.

Discussion

Despite a large body of literature documenting the comorbidity of schizophrenia and substance use disorders (

1,

3–9,

11), the order of onset of these conditions and their underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood (

2). The principal causal explanations for these associations, including the possibility of self-medication or the induction of psychotic symptoms through substance use, assume that disorders fulfilling diagnostic criteria result from far more dynamic or “micro” clinical phenomena. Investigating these causal associations therefore requires methods that allow assessment of the time-limited effects of psychoactive substances and within-day fluctuations in psychotic symptoms. This study is the first to examine these dynamic associations in community-dwelling persons with schizophrenia using methods capable of verifying order of onset in daily life. In aggregate analyses, both sad mood and psychotic symptoms experienced at a given moment during the day increased the risk of substance use over subsequent hours. In turn, the use of psychoactive substances was associated with later increases in the risk of psychotic symptom onset and with greater feelings of anxiety. All analyses controlled for the status of predicted outcomes as they existed at the moment of predictor variable assessment, thereby modeling change (as opposed to persistence) of the outcome variables. In this way, the findings provide strong support for reciprocal risks between psychotic symptoms and substance use in individuals with schizophrenia who demonstrate moderate overall impairment (

30).

In addition to these general associations, highly specific patterns were observed by substance class. Alcohol use was found to increase after reports of both anxious mood states and psychotic symptoms. However, no prospective association was observed in the reverse direction. These findings are similar to those of previous ambulatory monitoring studies of heavy drinkers (

18) and suggest that the pharmacological properties of alcohol as a CNS depressant may explain its increased or continued use after periods of anxiety or other strongly correlated symptoms. The unidirectional patterns of association for alcohol use are therefore more consistent with self-medication than with the alleviation of dysphoria more generally (

2). By contrast, cannabis use showed more complex patterns of association with psychotic symptoms and psychological states. Sad mood was associated with reduced risk of later cannabis use, while both anxious mood and perceived event negativity increased the risk. Predictors of cannabis use are therefore partially consistent with self-medication, but the reduced risk observed for sad mood may also reflect recreational use or specific social contexts associated with cannabis (

31). After the use of cannabis, the perception of event negativity decreased, but strong increases in psychotic symptoms were observed. These findings are consistent notably with cohort studies demonstrating that cannabis use is associated prospectively with an increased risk of psychotic symptoms or episodes (

32–36). However, the findings confirm for the first time the within-day directionality of this association in a manner that is inaccessible to standard clinical research protocols or to noncomputerized ambulatory methods (

12,

37). Secondary analyses of potential biases confirmed that these associations were generally independent of time-of-day effects, medications, and polysubstance use.

Although the development of psychosocial interventions for individuals with schizophrenia and substance use problems has been slow, recent treatment strategies have demonstrated success in reducing substance use as well as in improving functioning in community settings in this population (

38). The present findings should contribute to these strategies by identifying precise targets in the management of momentary risk factors for substance use, as well as by providing an empirical basis for psychoeducation addressing the immediate consequences of substance use. Evidence that certain psychoactive substances have an immediate influence on psychotic symptoms is also essential for basic neuroscience research on the biochemical processes implicated in these interactions. While the momentary effects of cannabis on psychotic symptom expression have been attributed specifically to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (

39), an important finding is that -psychotic symptoms were also more likely to follow the use of other illicit substances. This association was not observed in initial cohort studies that have implicated cannabis in the etiology of schizophrenia (

32), but it is consistent with research suggesting that substances other than cannabis may be associated with the onset of psychotic symptoms (

40).

The strengths of this study include the use of state-of-the-art ambulatory monitoring techniques allowing for the collection of data in the daily lives of community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia. To our knowledge, the sample is the largest to date to have participated in an ambulatory monitoring study of this disorder, and the study is the first to use computerized methods capable of confirming the temporal nature of associations between different forms of substance use and psychotic symptoms in daily life.

In interpreting the findings, it is important to note the study's focus was on substance use in persons already diagnosed with schizophrenia, not on the potential etiological role of substance use in the onset of this disorder. Ambulatory data collection raises concerns for participant burden and therefore limits the breadth of specific information that can be collected. Thus, in this study we focused on examining the risk of positive but not negative symptoms, and we did not examine certain prevalent psychoactive substances, notably nicotine. The contribution of nicotine to our findings cannot be quantified, and this issue should be considered in formulating conclusions. As the effect of anxiety predicting later cannabis use was no longer significant after we controlled for potential confound variables, this finding should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the assessment of substance use in this study did not include information on quantity of use, and the general category of other illicit substances does not permit conclusions concerning effects for specific types of substances. Substance use reports could not be confirmed with biological assays and may be influenced by social desirability bias. Further research is needed to investigate additional psychological and contextual variables associated with substance use in this population, as well as to examine the applications of ambulatory monitoring and novel technologies as a means of clinical intervention in daily life.