Suicide is the third leading cause of death in adolescents in the United States and the second leading cause in the rest of the developed world (

1,

2). Reducing suicide rates, particularly in individuals with severe mental illness, is a key public health target in several countries, including the United Kingdom and the United States (

3,

4). If psychiatrists are to help achieve these important targets, it is crucial that we be able to identify those patients who, at presentation, are most at risk of suicide, so that we can focus our interventions appropriately.

Psychiatric disorders are present in about 90% of adolescents who commit suicide (

5). Associations have been found between suicide and most psychiatric disorders (including substance use disorders, conduct disorder, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders [

1,

5]). Major depressive disorder is the most common single disorder, present in 35% of suicides (

5). Self-harm (with or without suicidal intent) is an important predictor of future completed suicide and is present in the recent histories of around 40% of suicides (

6). Adolescents who have attempted suicide in the past are up to 60 times more likely to commit suicide than those who have not (

5). Hopelessness has been found to be associated with suicide, although some studies found that this factor was confounded by the presence of depression (

5). Psychosocial factors associated with completed suicide include family psychopathology, family discord, abuse, and loss of a parent by death or divorce (

4,

7,

8). Peer relationship problems, including being bullied, have been found to be associated with suicide attempts but not with completed suicide (

7).

While treating depression effectively is likely to reduce suicide rates, it is also important to establish which factors increase the risk of suicidal behaviors among currently depressed adolescents. So doing will help us identify those patients who are particularly at risk for completed suicides and may reveal risks in need of treatment in their own right.

Nonsuicidal self-injury, often in the form of cutting (

8), is much less studied than suicide. Individuals self-injure for a multitude of reasons, such as to relieve distressing affect, to punish the self, and to gain attention. Most research on self-injurious behaviors has failed to distinguish the prognostic implications of suicide attempt with clear intent to die from nonsuicidal self-injury. One large all-ages cohort study demonstrated that an act of either type of self-harm is associated with a greatly increased risk of suicide over a 4-year follow-up (

9). Interestingly, there was no difference in suicide risk over time between those with suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm episodes at entry (

9).

Two studies have capitalized on data from large, randomized controlled treatment trials, investigating which risk factors are associated with self-harm events among depressed adolescents. Definitions of self-harm events were not the same in these studies, and only one of the studies measured nonsuicidal self-harm as a separate entity. In the Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) study (

10), 14% of participants had a suicidal event (5% made a suicide attempt) over 12 weeks of follow-up and 9% had an act of nonsuicidal self-injury. Baseline suicidal ideation and family conflict were significantly and independently associated with a suicidal event. The only predictor of nonsuicidal self-injury was a history of nonsuicidal self-injury before trial entry (odds ratio=9.6). In the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) (

11), 10% of participants had suicidal events (half of which were suicide attempts) over 36 weeks of follow-up. Suicidal events were predicted by baseline suicidality and high levels of self-rated depressive symptoms in univariate analyses. There was no separate category of nonsuicidal self-injury.

Results

A total of 192 participants in ADAPT had major depressive disorder at baseline. Valid data were available for all but one on baseline suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury, and for 163 on self-injury and 164 on suicide attempts during the follow-up period.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic and clinical data for those with baseline suicidality data and those with valid follow-up data for both suicide attempts and self-injury. There were no significant differences between those with and without follow-up data. There was a significant association between suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm in the month before baseline (self-injury present: suicide attempt in 15/58 [26%]; self-injury absent: suicide attempt in 12/105 [11%]; odds ratio=2.7, χ

2=5.6, df=1, p=0.018).

Baseline Predictors of a Suicide Attempt During Follow-Up

During the month before baseline, 28 adolescents (17%) made at least one suicide attempt. Fifty adolescents (30%) made at least one suicide attempt during the 28-week follow-up period. The risk of suicide attempt was lower across each measured month of the study than in the month before baseline (month preceding the 6-week assessment, 8%; month preceding the 12-week assessment, 7%; month preceding the 28-week assessment, 7%). Suicide and self-harm risk over the follow-up period by predictor variable is shown in Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article. A higher risk of suicide attempt during follow-up was significantly associated with suicidality, depression severity, hopelessness, the presence of a suicide attempt or self-injury in the month before baseline, and impaired family functioning, but not with treatment group, parental mental health, or friendship problems.

Multiple logistic regression demonstrated that only impaired family functioning (odds ratio=2.27, p<0.0005) and higher suicidality at entry (odds ratio=1.59, p=0.026) were significant independent predictors of a subsequent suicide attempt.

Self-injury was then added in the second step of the model, which is presented in

Table 2. Model fit significantly improved (Δχ

2=7.7, df=1, p<0.01). Self-injury and family function, but not baseline suicidality, were significantly associated with a suicide attempt. Similar results were obtained when presence of a suicide attempt in the month before baseline (yes/no) was used in the model instead of suicidality item: nonsuicidal self-harm and family function, but not prebaseline suicide attempt (odds ratio=2.4, p=0.08), were associated with a suicide attempt. Pairwise correlations of predictor variables are listed in

Table 3. With the exception of suicidality and prebaseline suicide attempt, all pairwise correlation coefficients were <0.5. Maximum variance inflation factor was low at 1.25.

ROC4 analysis demonstrated that the optimal predictor for a suicide attempt was prebaseline nonsuicidal self-injury (univariate relative risk=2.95). Among the larger subgroup with no prebaseline self-injury, the optimal predictor cutoff for a suicide attempt was family function, as assessed by the McMaster Family Assessment Device, with a cutoff of 25/26; 15/45 (33%) with scores >25 and 3/56 (5%) with scores <26 had a suicide attempt.

Baseline Predictors of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury During Follow-Up

Fifty-eight adolescents (36%) had at least one act of nonsuicidal self-injury in the month before baseline. Sixty adolescents (37%) had at least one act of self-injury during the 28-week follow-up period. The risk of self-injury was lower across all measured months of the study than in the month before baseline (month preceding the 6-week assessment, 26%; month preceding the 12-week assessment, 19%; month preceding the 28-week assessment, 16%). Table S1 in the online data supplement shows that self-injury in the month before baseline, high suicidality at baseline, high depression severity at baseline, baseline anxiety disorder and hopelessness, and female gender were significantly associated with a higher risk of at least one nonsuicidal self-injury incident during follow-up. Neither treatment group nor suicide attempt in the month before baseline was associated with self-injury during follow-up.

Table 4 shows that self-injury in the month before the baseline assessment was the most significant independent predictor of subsequent self-injury over the follow-up period. Other significant independent predictors were baseline anxiety disorder and hopelessness, female gender, and younger age.

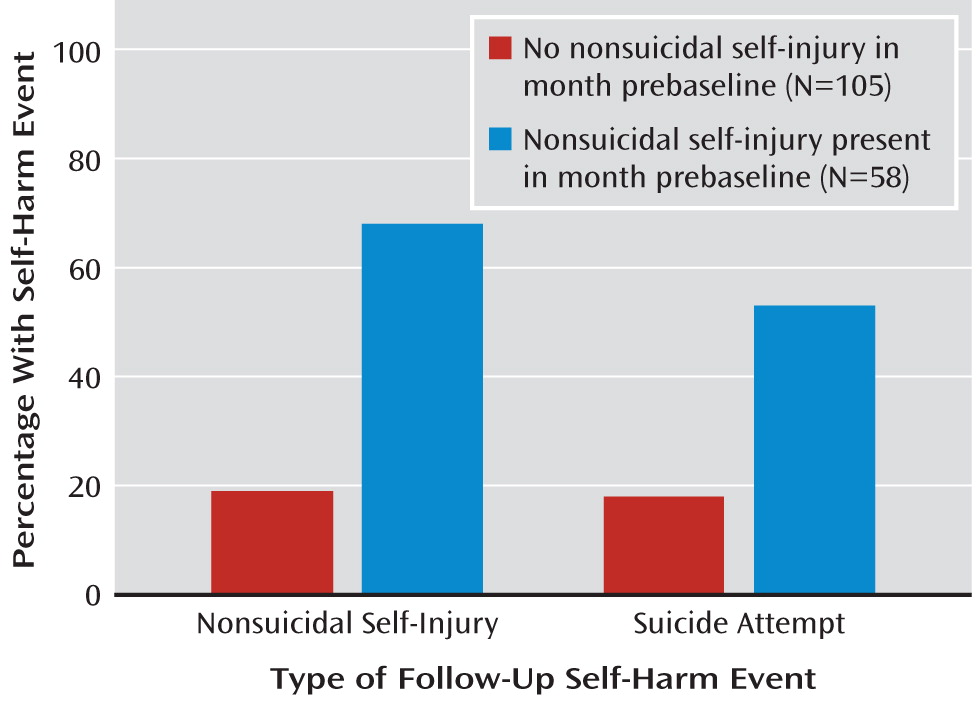

Figure 1 shows the risk of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm over the follow-up period among those with and without baseline self-harm. ROC4 analysis demonstrated that prebaseline self-injury was the most efficient predictor of self-injury (univariate relative risk=3.59).

Relationships Between Depression Outcomes and Self-Harm Events During Follow-Up

Table S1 in the online data supplement shows that high depressive symptoms at 28 weeks were significantly (p=0.001) associated with self-injury but not suicide attempts and that presence of one type of self-harm during follow-up was significantly associated with presence of the other type (odds ratio=2.5, p=0.007).

Discussion

In this article, we report the proportion of depressed adolescents with suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm at study entry and over 28 weeks of follow-up who participated in a large, randomized, pragmatic effectiveness trial of treatment of the acute episode. Measuring nonsuicidal self-injury separately from suicidal intent, at entry and at follow-up, is consistent with the form of reporting in the trial of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents (the TORDIA study) (

10).

Relative to the TORDIA sample (

10), the ADAPT sample had much higher risks of both suicidal (30% compared with 5%) and nonsuicidal (37% compared with 9%) self-harm acts. The higher level of self-harm may reflect the lower level of social functioning (as measured by the Children's Global Assessment Scale [

22]), and hence greater complexity, in the depressed adolescents recruited to ADAPT, despite similar levels of depressive symptoms compared with other studies (

12,

23,

24). More participants had suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury over the 28 weeks of the study than in the month before baseline. This difference may be methodological, resulting from the greater follow-up interval, as rates were lower for all three measured months of the study than for the month before baseline.

Our findings replicated those of TORDIA: suicide attempts were independently predicted by both baseline suicidality or recent suicide attempts and impaired family function. In addition, this study suggests that nonsuicidal self-injury in the month before baseline was a stronger predictor of suicide attempts than prebaseline suicide attempts. Since there was collinearity between suicide attempts and self-injury (r=0.38), this may be a type II error. Overall, this finding emphasizes the need for more research on the independence and validity of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal events in adolescents and their contributions to the emergence of depressive episodes.

Consistent with findings from TORDIA, we did not observe any association of suicide attempts with other nondepressive clinical features. There was no effect of parental mental health on subsequent suicide attempts. This suggests that family dysfunction per se is the risk marker rather than a surrogate for parental psychopathology. Interestingly, problems in personal friendships (personal disappointments), which are associated with depression onset (

25), were not associated with subsequent suicide attempts. This supports findings from previous studies demonstrating that in depressed adolescents, arguments with family members are by far the most common precipitants of attempted suicide (

26).

Overall, our results demonstrate that in our sample, adolescents with prebaseline nonsuicidal self-injury (suicide attempt risk=53%) had a 10-fold greater risk of suicide attempt during treatment than those with no self-injury and with reasonably good family functioning (suicide attempt risk=5%).

Compared with suicidality, self-injury over the follow-up period was associated with a different pattern of predictors. Thus, poor family functioning was not associated with self-injury, whereas hopelessness and anxiety disorder at baseline, as well as being both younger and female, were associated with self-injury but not with suicidality. As in TORDIA (

10), the largest predictor of self-injury was self-injury at baseline.

Higher depressive symptoms at 28 weeks were associated with greater risk of nonsuicidal self-injury. Possible explanations are that continued depressive symptoms lead to nonsuicidal self-injury, possibly to regulate affect, and that there is a subtype of depression characterized by self-injury that leads to a poor response to treatment.

Nonsuicidal self-injury is often seen as less serious than suicide attempts. However, our results support previous findings from a nonselective (all ages and not disorder specific) cohort study (

9) indicating that nonsuicidal self-injury is as likely as suicide attempts to predict future suicide attempts. Therefore, depressed adolescents with self-injury require the same high level of urgent assessment and treatment as those who have made a suicide attempt.

The majority of depressed adolescents with suicidal ideation do not attempt suicide. According to Joiner's interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (

27), people make serious suicide attempts only if they have the combination of a wish to die and the capability to act on that wish. Joiner's group has stated (

28) that repeated nonsuicidal self-injury may result in higher pain tolerance and reduced fear of death, increasing the capability to cross the boundary between suicidal ideas and acts. Our study is the first longitudinal study to demonstrate that self-injury is associated with future suicide attempts, independent of depressive symptoms, and provides partial support for this theory. It is equally possible that self-injury is a behavioral marker for neuropsychological processes that subserve suicidality, such as impaired behavioral inhibition, leading to impulsivity and a loss of emotion regulation.

Depression and nonsuicidal self-injury may reflect co-morbid disorders whose etiologies and prognostic significance are independent and require different approaches to treatment. Indeed non-suicidal self-injury has been proposed as a new category among childhood disorders for DSM-5 (

29). If this hypothesis is validated in further research, active treatments focused on self-injury should be provided alongside treatment for depression, as this may additively improve the likelihood of reduction in subsequent suicide attempts.

Trials to date in this age range have shown limited effectiveness in reducing suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm. In ADAPT, TADS, and TORDIA, the addition of CBT did not lead to a statistically significant additional reduction in suicide attempts or in nonsuicidal self-injury (

12,

23,

24). These trials were powered to test for treatment effects on depressive symptoms, however, not the rarer outcomes of self-harm. A recent small study of attachment-based family therapy shows promise, with reductions in suicidality in depressed and nondepressed adolescents compared with standard treatment (

30). Trials of a group therapy using CBT and dialectical behavior therapy techniques have had contrasting results, with both lower (

31) and higher (

32) rates of suicide attempt in the intervention compared with the comparison group. A brief home-based family intervention for children and adolescents after self-harm has been shown to reduce suicidality in nondepressed but not in depressed subgroups (

33). Dialectical behavior therapy, while demonstrated to be effective in reducing suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm in some studies in adults (

34), has not been proven to be more effective than treatment as usual in reducing suicidal or nonsuicidal self-harm in adolescents (

35,

36). Further research is needed to identify effective and deliverable interventions for suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm in depressed and nondepressed adolescents.

Limitations

Because this is a secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial, there is a risk of type I errors. However, as the main results replicate those of another trial (TORDIA), it is more likely that these variables are true risk factors for suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm. Unlike in TORDIA, data on self-harm over the 28 weeks of the study were collected only at the 28-week follow-up assessment, which may have led to underestimation of self-harm events (

10). It also means that we cannot distinguish between patients who self-harm only at the beginning of treatment (who may stop self-harm once depression is successfully treated) and those who have persistent self-harm throughout treatment. It is possible that adolescents who remain depressed are more likely to remember self-harm over the previous 28 weeks.

Suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm data were collected by three research assessors. Interrater reliability was not assessed, so there may have been inaccuracies in classification. Data were not collected on several variables that may have affected suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm, including drug and alcohol use, self-harming behavior prior to 1 month before baseline, family history of self-harm or suicide, environmental adversity (including abuse), impulsivity, and personality dimensions. This study was carried out on clinic patients treated with SSRIs. The range of comorbidities and illness severity in the sample makes it representative of depressed adolescents seen in U.K. National Health Service clinics. However, the results may not be generalizable to patients receiving treatments other than antidepressants. Finally, the results should only be generalized to depressed adolescents: nonsuicidal self-injury is common in nondepressed teenagers and may not have the same effects on risk of suicide attempts in the population at large.

Clinical Implications

Suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm are both significant risks for depressed adolescents treated in the clinic. The presence of family dysfunction, high levels of suicidality, and recent self-harm (suicidal or nonsuicidal) should alert us to a high risk for future suicide attempts. The presence of recent nonsuicidal self-injury is by far the strongest predictor of future nonsuicidal self-injury. The lack of positive results to date from trials that offered specific treatments focused on self-injury indicates the need for the development and testing of new treatments.